I can’t tell you the location of the secret tank. Going there would mean trespassing on someone else’s land, and Texans take trespassing seriously. Plus, swimming there is dangerous. I can’t recommend it. I will tell you this, though. Sometimes it’s worthwhile to revisit the brash indiscretions of youth, consider them, be tempted by them, and then step back.

Desert dwellers crave a satisfying soak and will go to some lengths to find water. We’ve slogged plenty of times to Balmorhea. We’ve sneaked into the pools of fancy hotels and gone for covert late-night dips in the neighbor’s aboveground pool. But we had not been to the secret tank in more than twenty years, my husband and I. A few weeks ago, we went again.

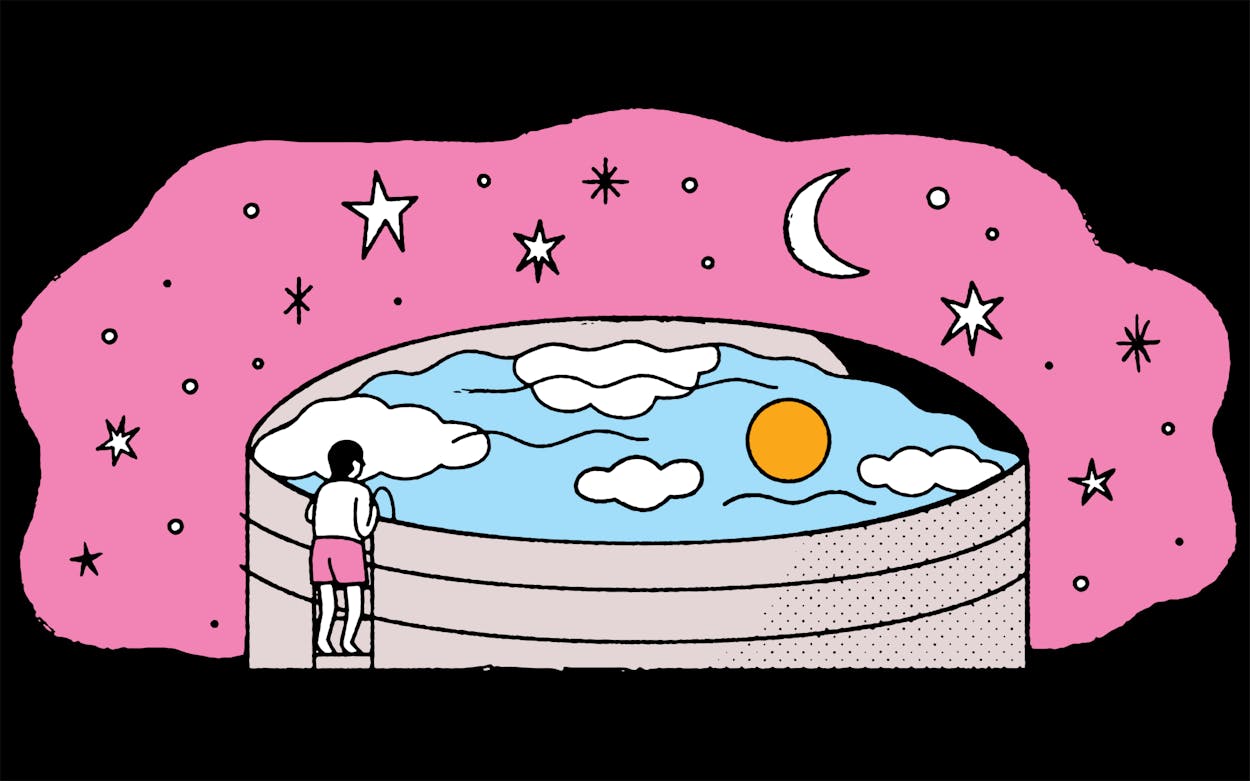

The secret tank stores thousands of gallons of water. The tank itself is steel and very tall, maybe 35 feet tall. Hundreds of rivets hold back the water’s tremendous pressure. A skinny ladder affixed to the side of the tank leads to the top. Up top, the water is level with the rim, a flat, mirrored sheet that reflects the blue blueness of the sky. It is perilous, dizzying. “It’s twice as tall as I remember,” I said. “Usually things are shorter than you remember, but this is taller.”

We stared at it awhile, at the tank’s breadth and height. “I first came with Esteban,” Michael said. “He didn’t go in, but I did.”

“I can’t believe everyone used to do this,” I said. “I came once with those two cowboys. I was too chicken to go in, but they did. Now they’re both family men, with kids almost out of high school. I never see those guys around anymore.”

“Everyone was young then,” Michael said. After a moment he said, “It wasn’t really swimming, was it?

Just floating, but like floating in the sky and floating in the water.”

“I came here once with you,” I said.

“Did we go in?”

“I remember your head above the water,” I said. “I remember the sky and the mountains and all the green below. But maybe I dreamed it? Or manufactured the memory?”

“Maybe,” Michael said. “Getting over the top was scary. The ladder felt slimy and slippery. It was hard getting over the top, and it was worse climbing out.”

The tank’s rim loomed far above. I thought about climbing the ladder and swinging over the top, the moment of that vertiginous straddle. On one side, the cold, deep water. On the other side, the air straight down. I imagined falling. I thought, we’re so fragile, so foolhardy.

“I don’t want to talk about going over the rim,” I said.

We poked around. We’re not the only ones who know this place. Someone had stacked lumber as a step to reach the ladder’s lowest rung. Nearby lay a torn pink pool noodle. Mustard weeds nestled an almost-empty orange Fanta and an unfaded granola wrapper. The Bacardi drinkers were neater in their habits. They’d set their bottle atop a rock, cap on, the glass gone chalky with age.

Fifty paces away were two seeps, where water pooled darkly under stunted cottonwoods and a rash of vivid green mesquites. Here, too, was evidence of people. A refrigerator rack atop rocks and concrete formed a makeshift grill, now fallen inward. Two crude concrete benches. Whose good times were made here? What happened to those people and where are they now? All of them gone. Bees and tall weeds, a snaky place. Better not get too close. The water in the seeps was quiet, but the breeze in the cottonwood leaves overhead sounded like rushing water. A hornet shot past.

Over by the tank, Michael stood smiling and squinting in the sunlight.

“I’m going in,” he called out.

I didn’t answer.

“Nothing’s going to happen.”

“That’s not a good idea,” I said.

“But I want to,” he said. “It’s kind of hot out. I’m going in. I can still do it.”

Water trickled steadily from the big valve at the base of the tank. The water waiting up top would be cool and still.

“I came here with Chris,” Michael said.

“Did Chris get in?”

“No, Chris didn’t get in. He waited for me. I came with Rich.”

“Did Rich go in?”

“Yeah, Rich would do anything.”

Michael considered the tank, his hand shielding his eyes. He was still smiling faintly.

“I’m going in,” he said.

I walked across the rocks, toward the truck. I knew he’d find joy in the water; happiness would buoy him as much as the water itself. A dunk in the secret tank would hurtle Michael twenty years back in time, to starry nights and long-ago friends, when a dash of illicit recklessness was a keen, sharp pleasure, exhilarating and free-feeling. Up top he could be suspended in water, suspended in time.

“Can I wait in the truck?” I said.

Michael’s socks were already in his hands. His denim shirt was halfway unsnapped. He looked surprised. I didn’t say this part out loud–that I didn’t want him to go, that I didn’t want a time when I couldn’t see him in the sunshine, when things aren’t as they are right now. That I know our lives are halfway done or more, that the time is coming, someday, when we won’t be together and healthy and strong, that there is suffering ahead, bodies that betray us and parents who grow old and die, and I don’t want any of it. I don’t want to jeopardize any of the minutes we have left. I didn’t say these things, but I thought them. Michael gazed at me.

“All right. If it makes you nervous, I won’t go in,” he said.

“I’d rather you not, yes.”

Michael used to hitchhike. Now he does not. He used to trespass into dilapidated cabins and abandoned rattletrap buildings. A Class B misdemeanor at age 21 took care of that urge, mostly. Half a mile away, dust rose from a truck and trailer as it pulled into the drive of a house that’s there. We were not so alone after all. Michael jammed his feet into his boots. He picked up the binoculars we brought and the bird book.

“It’s better that I not go in,” he said. “They might call the law, and they would be right to call. We shouldn’t take the risk. It’s still a beautiful day.”

He looped an arm around my neck.

“Let’s go.”

- More About:

- Water