IT’S REALLY NOT SO STRANGE that the star of the Southwestern Writers Collection is the simulacrum of a one-legged body taken from the set of a television show. First, the fictional character who inhabits that body is perhaps the best known in Texas literature: retired Texas Ranger Augustus “Gus” McCrae, from the Larry McMurtry novel Lonesome Dove, as played by Robert Duvall in the 1989 miniseries of the same name. McCrae was the wry, brave, loyal rogue of a cowboy who dies a sad, heroic death rather than submit to a lesser life, one in which he wouldn’t be able to, say, kick pigs. Duvall made McCrae seem like a real person, and real people come all the way to the seventh floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library, on the campus of Texas State University, in San Marcos, just to see his fake body.

The second reason why it’s not strange that this writers collection has stuff from TV is that it’s not your average aggregation of dusty old manuscripts and arcane knowledge. For example, across from other various Lonesome Dove props grouped in glass display cases (such as the large hat worn by retired Texas Ranger Woodrow Call, or Tommy Lee Jones) stands a handmade camera that was used in the town square of Nuevo Laredo for seventy years, recording generations of locals and tourists. A few feet away is an exhibit showing pieces of a 280-foot mural of a cattle drive painted in 1951 that will soon be rehabbed and put on the walls of the library. Just down the hall sit an Austin City Limits archive; a dozen boxes of songs, posters, and running shoes donated by Willie Nelson; and a collection of some 13,000 images, many from Mexican photographers. And then there are the production archives from King of the Hill, including presumably life-size cutouts of Hank and Bobby Hill.

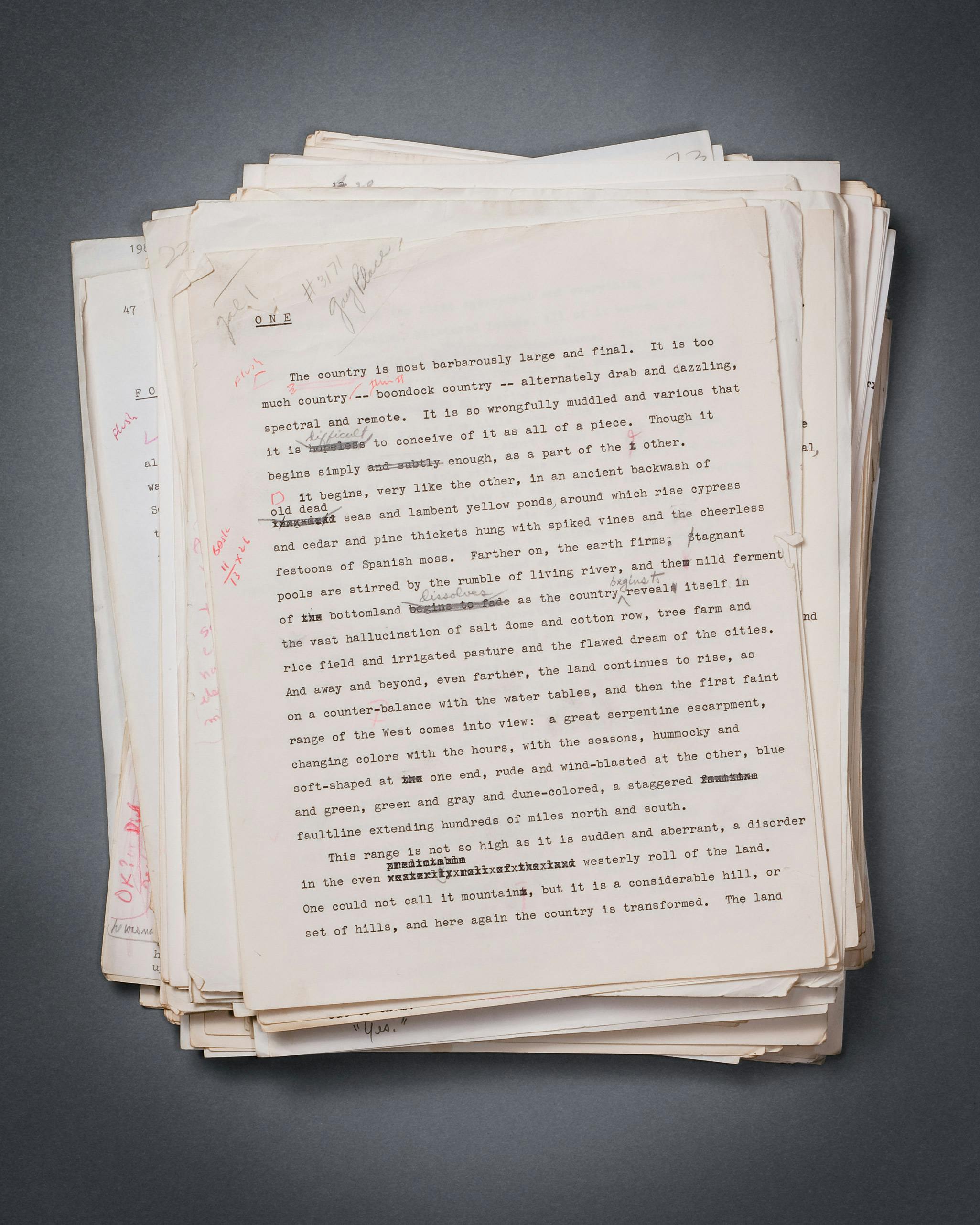

Oh, there are plenty of dusty old manuscripts from Southwestern writers at the Southwestern Writers Collection, which is celebrating its twenty-year anniversary. You can sit down at the large pine table in the main room, in front of the oak desk of J. Frank Dobie, the Moses of Texas writers, and ask to see the original manuscript for The Gay Place, by Billy Lee Brammer, in which he crosses out “begins to fade” after “the mild ferment of bottomland” and replaces it with “dissolves.” Or some of the tens of thousands of letters written by and to noted epistomaniac Larry L. King. Or photos John Graves took on the 1957 canoe trip he later memorialized in Goodbye to a River. Or the notes and papers of journalists, novelists, and troublemakers such as Edwin “Bud” Shrake, Gary Cartwright, William Broyles Jr., Jan Reid, Dick J. Reavis, Joe Nick Patoski, Stephen Harrigan, and Sarah Bird. (All of those writers have contributed to this magazine, whose archives are also held at Texas State.)

The main explanation why the writers collection is as much about photography, film, TV, and music as it is about writing is that its founder, Bill Wittliff, is too. Wittliff, with his wife, Sally, founded Encino Press in 1964, publishing Texas writers, including his mentor Dobie and fellow upstart McMurtry. By the seventies Wittliff had developed into a noted photographer, after spending months taking a gorgeous series of photos of vaqueros working on a northern Mexican ranch. In the eighties he became a successful screenwriter, writing movies such as Raggedy Man and Barbarosa and befriending Willie Nelson. In 1986, one year after buying Dobie’s desk and some of his other artifacts at an estate sale, the Wittliffs founded the writers collection. Their choice of the term “Southwestern” was a conscious one: They didn’t want to limit the archive to Texas, especially given how much Wittliff, like Dobie before him, was enamored of all things Mexican. The Wittliffs knew they would need a permanent home for the collection and found one at Southwest Texas State University (as Texas State was called then). The school was opening a new library in 1990 and promised to give the SWWC, which would exist under the umbrella of the university’s Special Collections, a part of the top floor, as well as to let Wittliff consult with the architect.

The collection occupies its own space on the seventh floor, and walking through the ascetic, fluorescent-lit library and then encountering the brown longleaf pine double doors and windows is like finding the entrance to Narnia at the back of the closet. With Saltillo tile and handmade sconces, the museum feels like a clean adobe gallery in Laredo or Taos. “We wanted to create a friendly, human space,” says Special Collections curator Connie Todd. Members of her staff will talk to you all day long about, for instance, Dobie’s love-hate relationship with the University of Texas or the strengths of various female Mexican photographers (in 1996 Bill and Sally founded the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography) or the inspiration for a certain Texas short story. “We’re a personal place,” says Todd, “where people can come and talk to us about who these people were.”

Admission is free and open to the public, and sometimes students, many of whom aren’t even aware of the collection’s existence, wander in through the double doors from the stacks and stare at Gus’s Colt Dragoon pistol or Dobie’s only surviving white linen suit (he was buried in the other) or a photograph taken at a Mexican street fiesta. And if they know exactly what they’re looking for, they find themselves sitting down and holding in their own hands a piece of paper containing a favorite paragraph in which a favorite writer worked the words over and over until he found the perfect one.

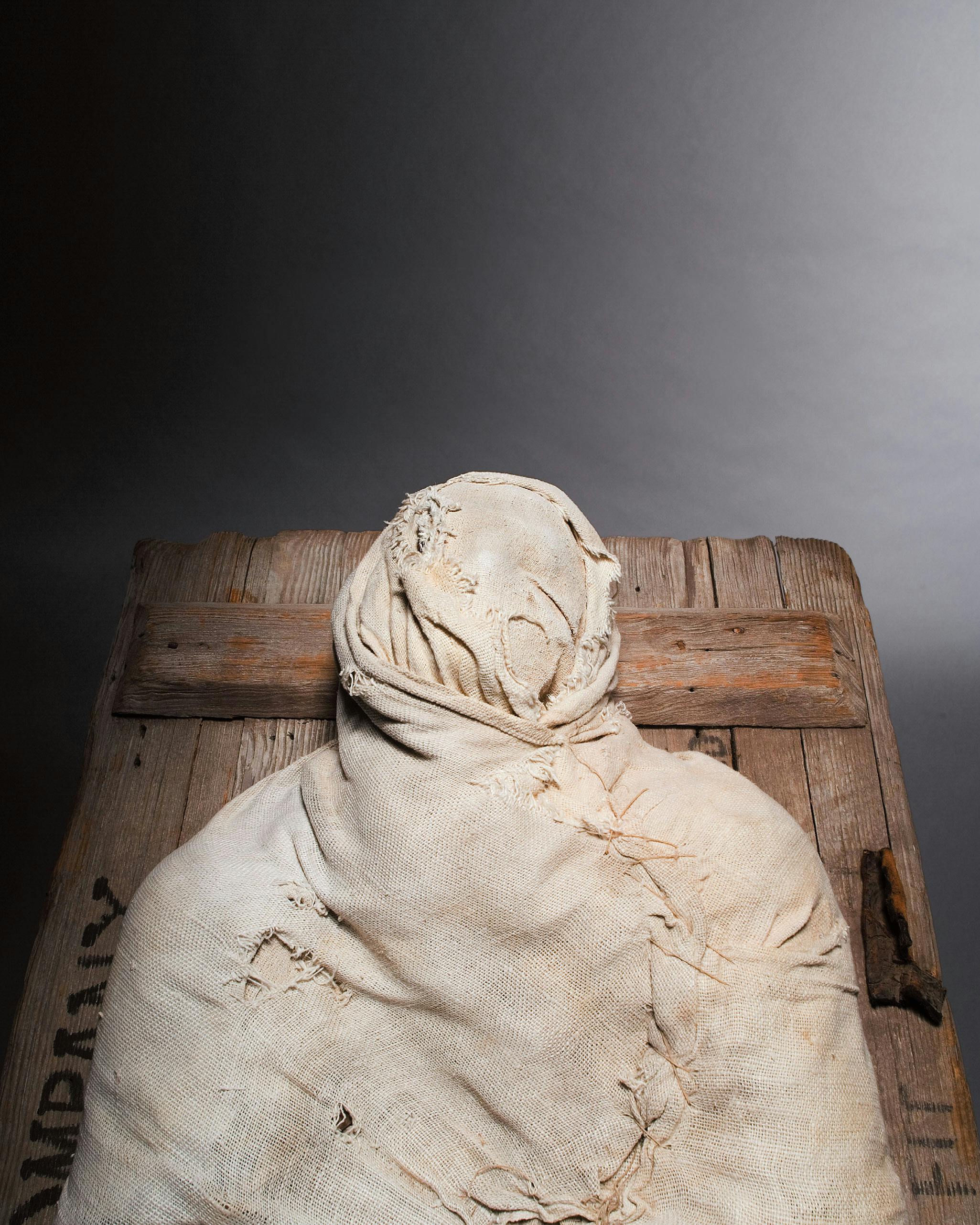

Gus’s Body from “Lonesome Dove”

Robert Duvall has had roles in some of the finest American movies, but his favorite was Augustus “Gus” McCrae in Lonesome Dove. The voluble Gus has become one of our more enduring characters, especially as teamed with the reticent Captain Woodrow Call, played by Tommy Lee Jones. The Southwestern Writers Collection has the show’s production archives, including scripts, costumes, guns, boots, and even the spear that killed Danny Glover’s character, Joshua Deets. But everyone wants to see Gus’s body. Except, founder Bill Wittliff remembers, the man who played him: “I brought Duvall over here, and he wouldn’t get close to this.”

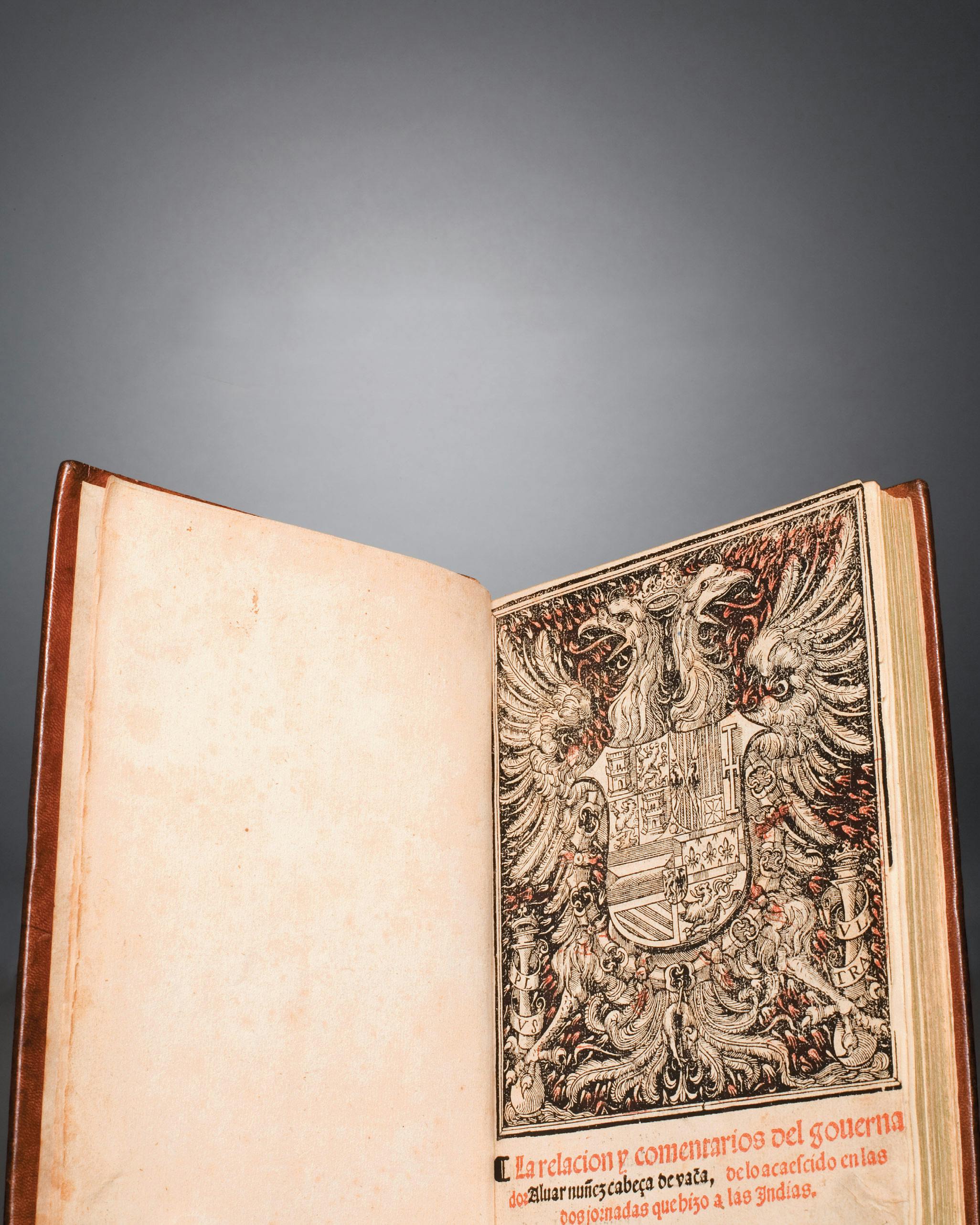

Cabeza de Vaca’s “La relacion”

La Relación is the Gutenberg Bible of the collection, a rare 1555 edition. The book was written by Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, a member of an early Spanish expedition to the New World who became an accidental explorer after his ship wrecked near Galveston in 1528 and he wound up wandering through parts of modern-day Texas and Mexico for eight long years (almost everyone else died of drowning, disease, or violence). He wrote La Relación as a report to the Spanish king, telling of his experiences as a slave and medicine man to various Indian tribes as well as describing the flora and fauna of the strange new world, including the buffalo. He was, in short, the first Southwestern writer.

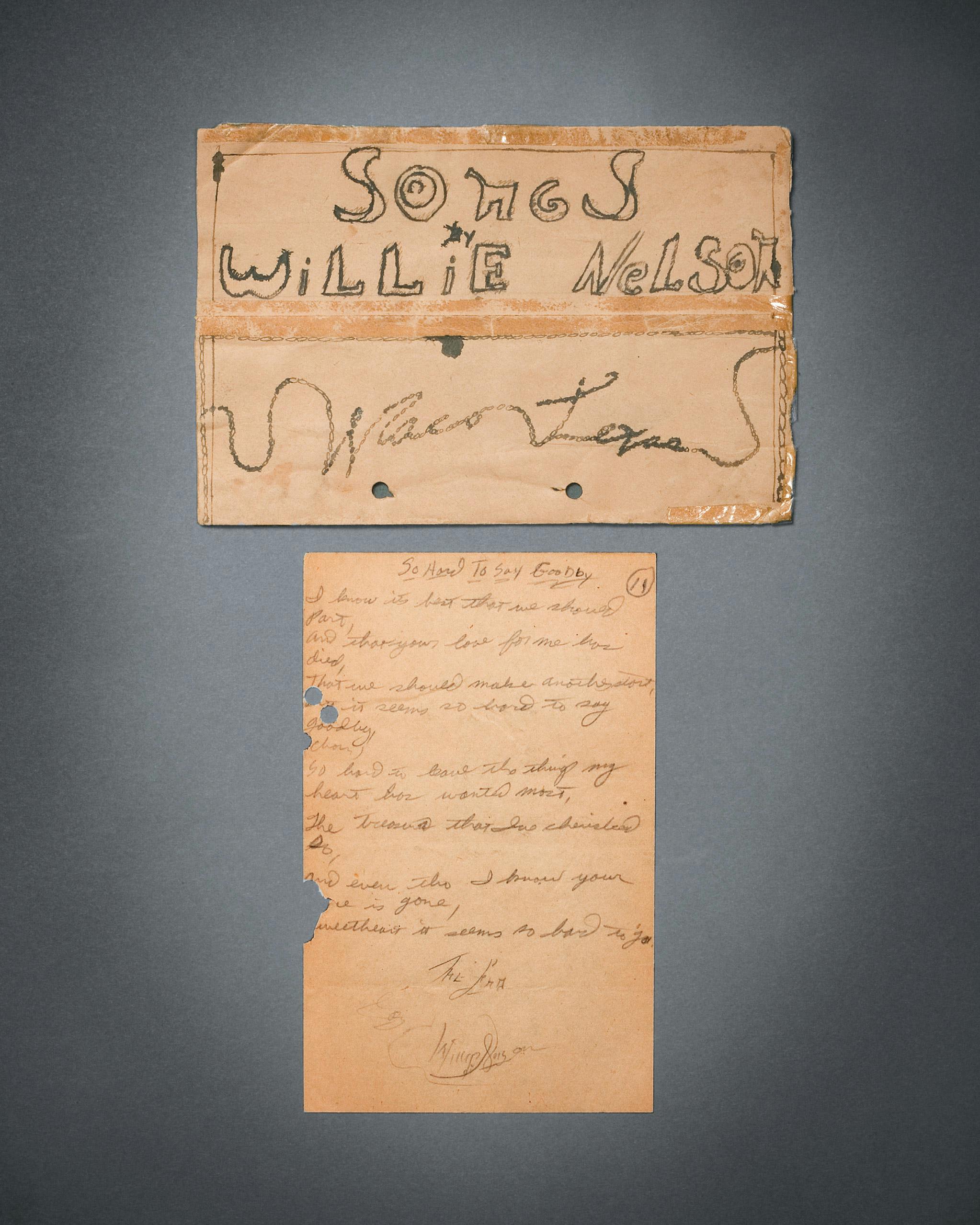

“Songs by Willie Nelson”

The titles sound like vintage Willie compositions: “I’ll Wander Alone,” “Hangover Blues,” “Long Ago.” But he was only eleven years old when he wrote them (the kid was already playing with a polka band in Abbott) and collected them in a notebook. The front says “Songs by Willie Nelson” and the back “Howdy, Pard.” On one page he practiced writing his name, as if he knew it would come in handy in the future. Other Willie stuff includes letters, posters, song lyrics written on hotel bar napkins, and documents from the singer’s troubles with the IRS—including the sticker that agents glued on his Pedernales studio door giving notice of confiscation.

Letters of Recommendation for Katherine Anne Porter

Porter was born in Indian Creek and raised in Kyle, but she left Texas in her twenties and rarely looked back, feeling unappreciated by her home state and donating her papers to the University of Maryland. In the mid-seventies, Roger Brooks, the president of Howard Payne University, in Brownwood (near Indian Creek), wanted to give Porter an honorary degree, but first he had to convince the board of regents that she was worthy. So he asked dozens of well-known writers to send letters to the board, telling how important Porter was; 88 did, including Norman Mailer, John le Carré, and James A. Michener. It worked, and Porter returned for the ceremony. She also visited her mother’s grave in Indian Creek and was so moved that she directed that she too be buried there. In 1980, she was.

Buck Winn’s Cattle Drive Mural

When it was painted in 1951, James Buchanan “Buck” Winn’s 280-foot-long mural showing an epic cattle drive was the largest in the world. It hung in the Pearl Brewery, in San Antonio, until a renovation in the seventies brought it down and it was sliced into eleven panels. The collection has three of them, each 28 feet long, and each is an elaborate, gorgeous work, with that lofty feel of the Works Progress Administration post office murals. Winn, from Celina, actually did many public murals in the thirties, mostly in Dallas, including several at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition.

Russell Lee’s First Camera

Lee was a former chemical engineer trying to be a painter in Depression-era New York City when a friend advised him to get a camera to help him with the details. In 1935 Lee did, leaving a painting unfinished and never picking up a brush again. That camera was this Contax, and with it and others Lee would go on to be the most prolific of the Farm Security Administration photographers traveling the country during the Depression, taking pictures in 29 states and becoming known for his heartfelt shots of poor tenant farmers, homesteaders, and their families. After World War II he spent time taking photos of the poor in South Texas; he also shot for the Texas Observer, and in 1965 he became the first professor of photography at the University of Texas at Austin.

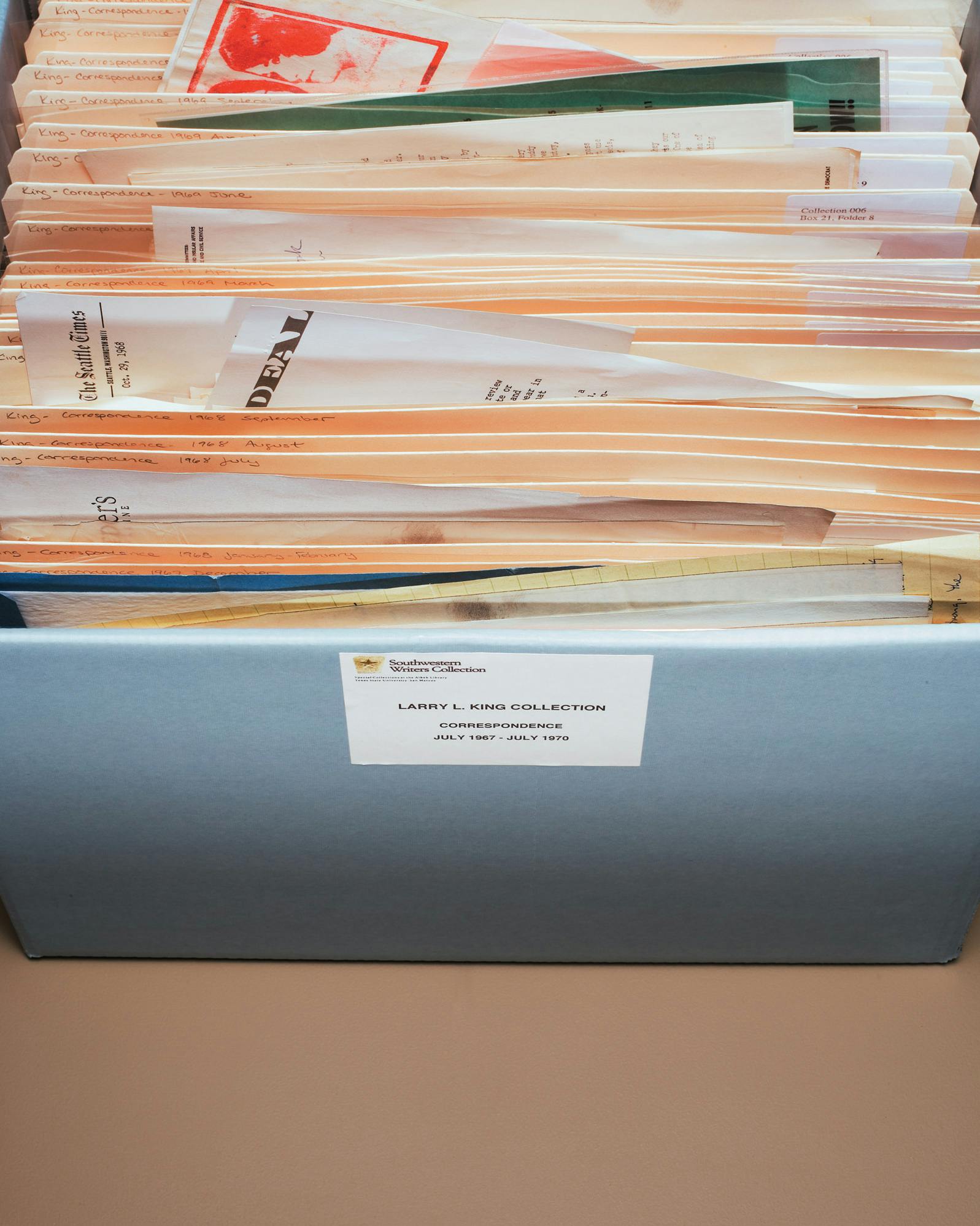

Larry L. King’s Letters

King writes a lot of letters. And he saves them. And then he sends them to the collection, some 3,000 pages a year. In the past he typed on carbons; now he prints out e-mails. The collection has about 50,000 pages: receipts, invitations, Christmas cards, and letters to and from Norman Mailer, William Styron, Mo Udall, and Ted Kennedy. The funny thing is, in 1964 King’s first wife burned much of his stuff, including his letters (such as the ones to FDR telling him how to win the war); those here are only from age 35 on. King knew they would be important someday, and he was right.

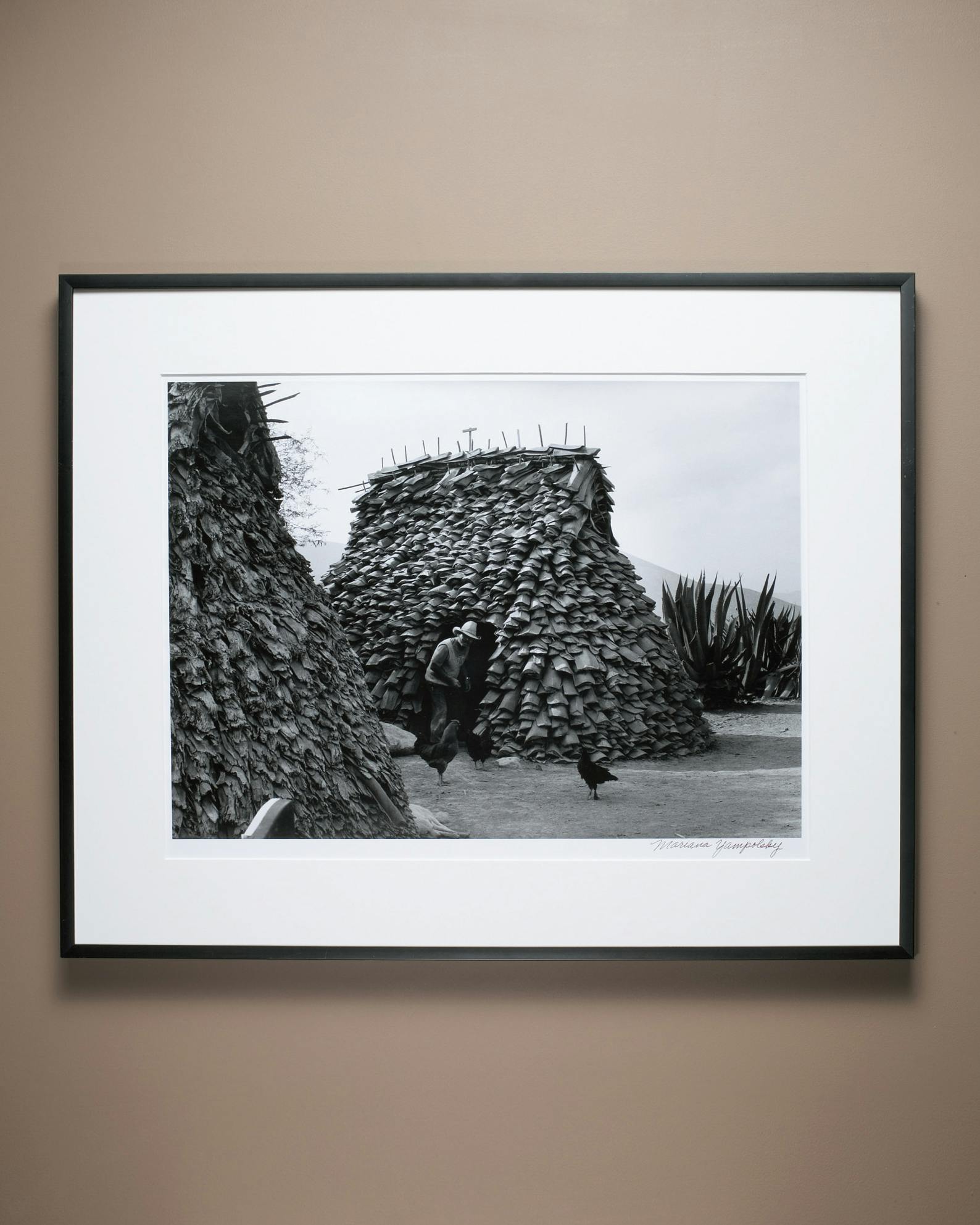

Mariana Yampolsky’s “Maguey House”

The gran dama of Mexican photography was born of Russian and German parents near Chicago in 1925. Yampolsky wound up living permanently in Mexico in the mid-forties, taking thousands of photos of the country’s common people doing regular things, imbuing them with the same dignity that Russell Lee and Dorothea Lange (two of her heroes) had given Depression-era folks in the United States. Ever since curator Todd contacted Yampolsky in 1994, the artist has helped Wittliff meet dozens of Mexican photographers, becoming, in Todd’s words, the gallery’s fairy godmother. The collection has more than two hundred signed prints of hers, including this one of daily life outside a home made of maguey leaves.

Candy Barr’s gloves

Note the tips of the gloves, the paint worn down from the continual friction of being removed, finger by finger, night after night. Candy Barr, known by her mother as Juanita Dale Slusher, was the most famous stripper, pot smoker, and all-around bad girl of the fifties and early sixties, at least in Dallas. It wasn’t all fun and games: Barr was forced to act in a porn film at fifteen, was abused by her second husband (whom she eventually shot), and spent three years in jail for marijuana possession, where she wrote poems that she later published as A Gentle Mind … Confused. The collection has various things from her life, including silver boots, bathing suits, and a stripping license (fee: $50).

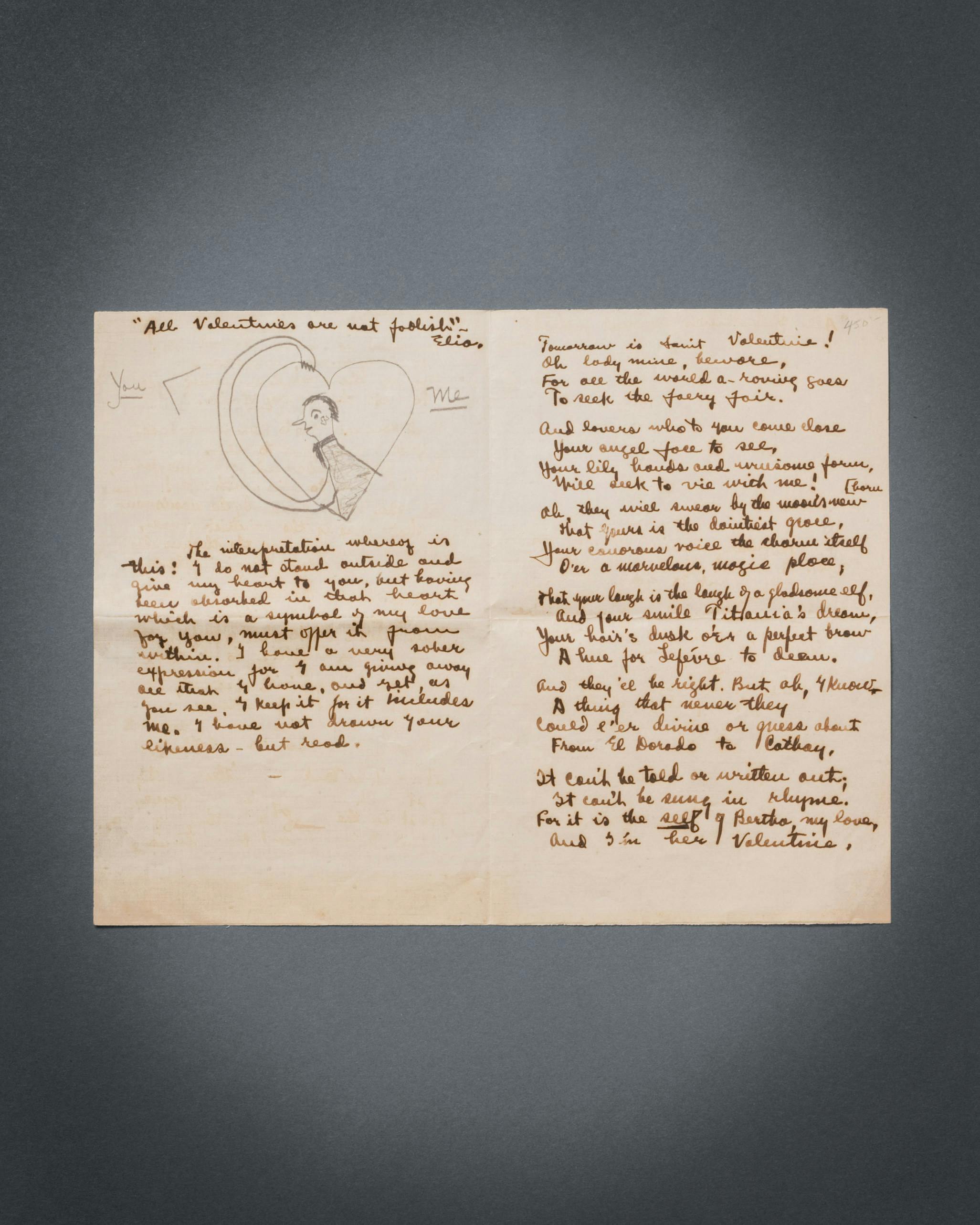

J. Frank Dobie’s Valentine to his Wife

Dobie, the son of South Texas ranchers, who would go on to write more than a dozen books about the cowboy way and the state’s rough folklore, also loved English romantic poetry, as seen in this valentine he sent his new bride, Bertha, during World War I. Later Dobie would call her “the most incisive and the most concretely constructive critic I have ever known,” but in 1917 he was more romantic, in his own brainy, up-from-the-scrub-country way. “… Your laugh is the laugh of a gladsome elf/And your smile Titania’s dream,/Your hair’s dusk o’er a perfect brow/A hue for Lefévre to deem.”

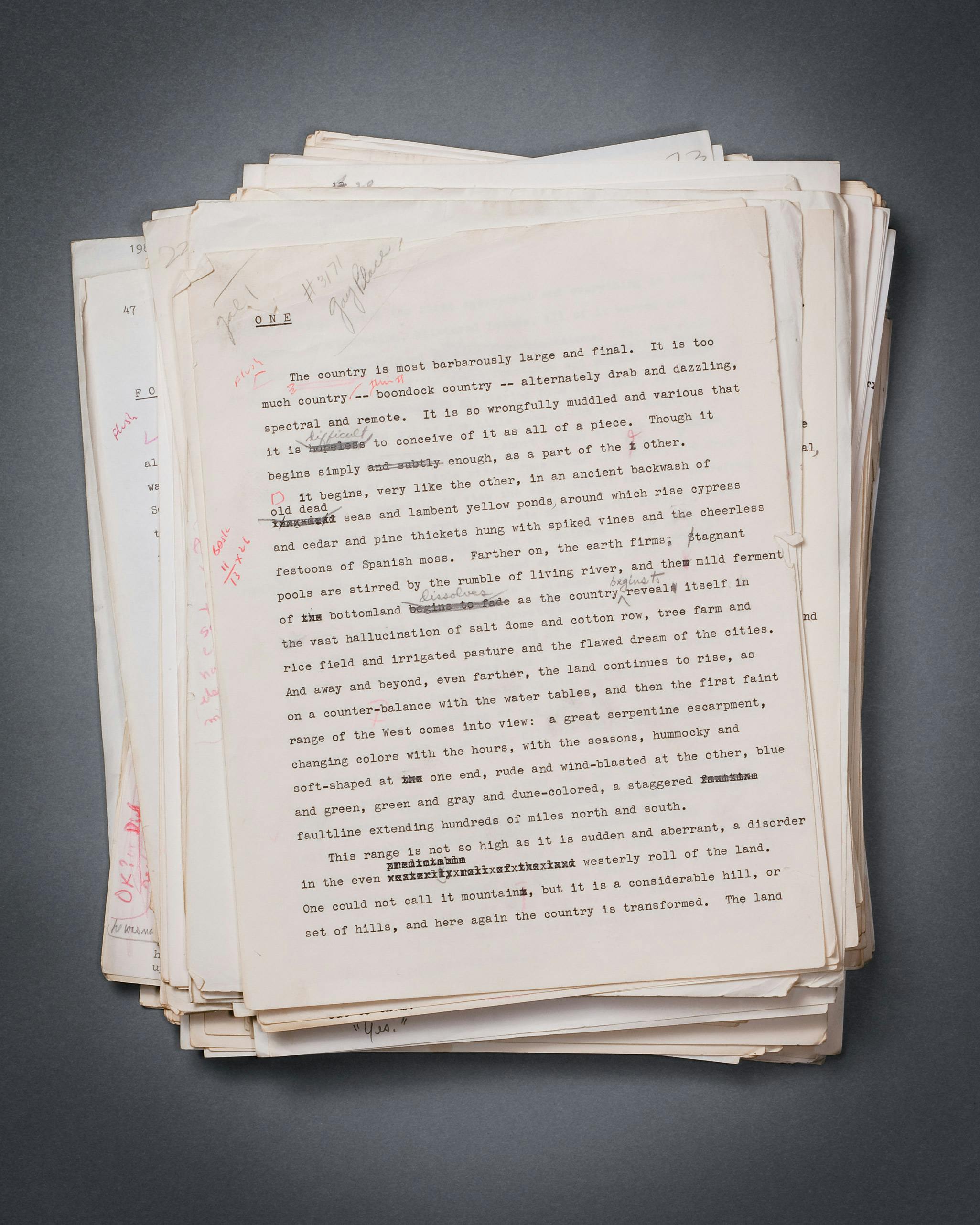

Billy Lee Brammer’s Manuscript for “The Gay Place”

At some point in 1958 or 1959, Brammer wrote perhaps the most celebrated first lines in Texas literature, describing the Edenic Austin of the time. The book would become the closest thing to the Great Texas Novel and also make Brammer a star. He never finished the sequel, Fustian Days, either because of simple writer’s block, brought on by the greatest of expectations, or just simple drug abuse (Brammer would die of an overdose in 1978). Besides these two manuscripts, the collection holds plenty of others from Brammer’s career, including a phony 1965 interview with the Mailer-esque Norma Maelstrum, in which Brammer undams altogether his stream of consciousness.

John Graves’s Paddle

This is one of the paddles Graves used to transport himself and his dachshund puppy along a stretch of the Brazos River for three weeks in the fall of 1957, resulting in the classic Goodbye to a River, the journey into the self and the soil and the history of Texas that earned the author comparisons to Thoreau. The paddle has Graves’s 1957 Fort Worth address written on it in ink; when he moved to rural Glen Rose in 1970, he took it along but eventually threw it onto his woodpile, where the elements and the cattle cracked it into pieces. His friend Wittliff retrieved them and glued the paddle back together.