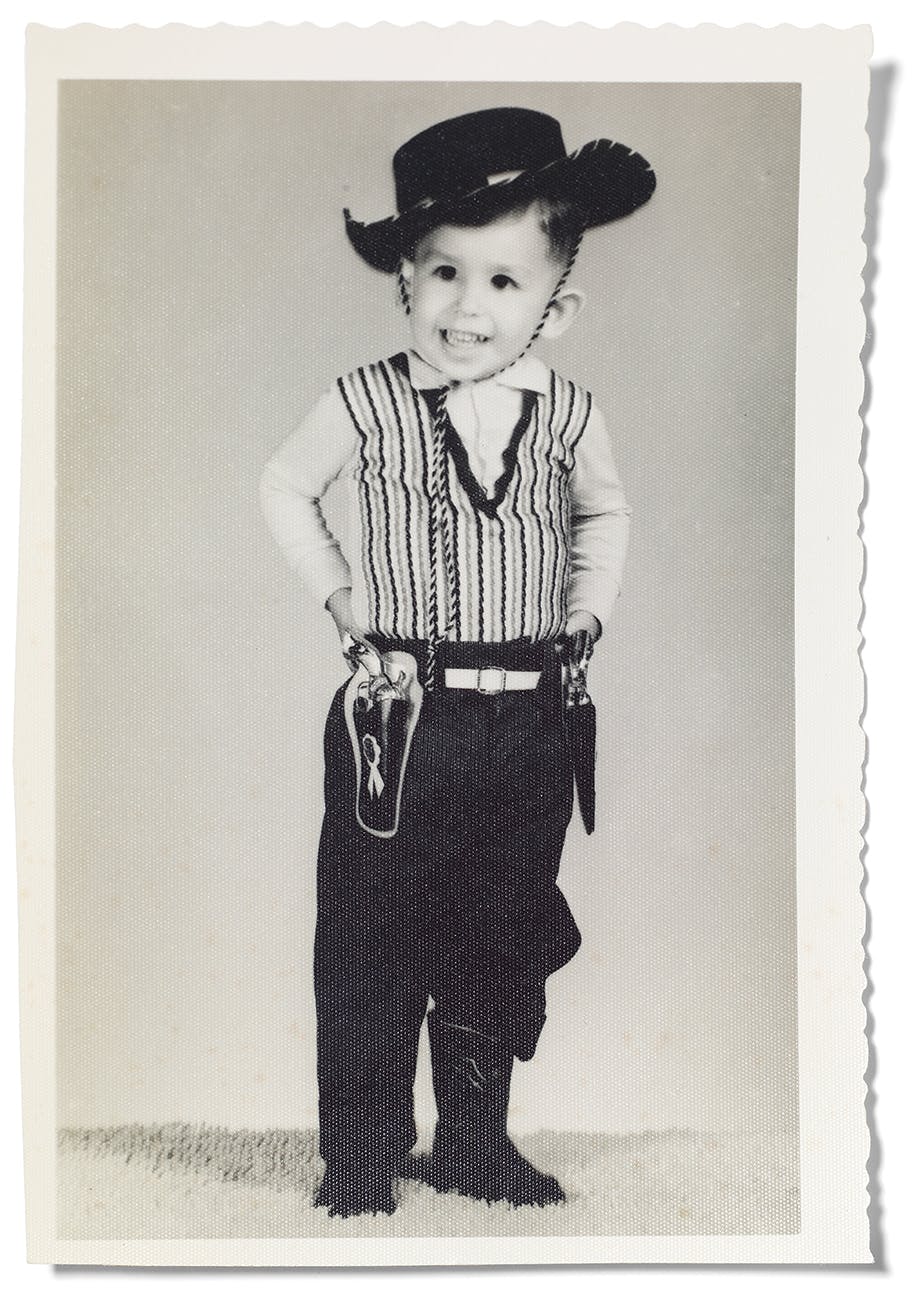

I recently went searching for the long-lost ranchito just south of San Antonio that my father bought with a Veterans’ Land Board loan in 1960, when I was three years old. Rancho Santos wasn’t a grand Texas spread, but it was 125 thickly forested sandy acres, apparently untouched since creation time, where we could leave modern comforts behind and live, more or less, like our Mexican vaquero forebears, or so my father liked to imagine.

There was a humble wood-post corral, occupied by an ornery Shetland pony named Brown Beauty; an old galvanized metal papalote windmill that kept an algae-rimmed cement tank filled; and a military surplus Quonset hut, lavishly furnished with canvas cots and a wood-burning potbelly stove. Along with my parents and brothers, my aunts, uncles, friends, and cousins would retreat there on weekends to barbecue a cabrito, attempt white-knuckle rides on the cantankerous Brown Beauty, and listen to my dad sing and play guitar once the sun went down and a big fire was lit. Sometimes, it seemed the ancestors might be listening from just beyond the treetops.

Years later he sold the ranch, under protest, to buy a house in the suburbs that would give me and my brothers a chance at a decent public education, and we never saw the land again. On my latest expedition, I took a right off congested Southwest Military Drive onto Pleasanton Road, passing the aging Griff’s burger joint landmark, passing Loop 410 and the outer 1604 loop, both new since I was last there. The gritty city streets lapsed into rural roads through scrubby open fields that vaguely stirred memories of our journeys long ago, from our Dellview neighborhood home at the northwest edge of the city. There was still a lot of countryside in the San Antonio de Béjar I grew up in; you didn’t have to drive far in any direction to see cattle grazing.

“Our old San Antonio was six miles by six miles,” one elder Bejareño recently remembered with me.

Farther down the road, I recognized the stinky pond we’d wince to sniff, quickly rolling up the windows of the station wagon. On the other side, set off from the road a bit, I saw the last ruins of an old black clapboard house. My brothers and I knew it to be the residence of the local witch and would duck as we passed so she’d not be able to catch a glimpse of us and thereby snatch our souls.

Astoundingly, the ubiquitous tentacles of housing developments, strip malls, and their accompanying clatter of sprawl haven’t reached this far south of the city yet. But much of the land has been cleared, mesquite and oak stands and brush thickets that once swathed the land swept away, setting the stage for the inevitable arrival of the earthmovers. Turning off another familiar road, I looked for the truck path that led to the rusty ranch gate, but to no avail—it was gone, probably swallowed up into a larger tract long ago. A piece of my old San Antonio had been erased.

No matter where you come from, some of the dearest places of your earliest memories sooner or later disappear entirely from the face of the earth. You can lose much of the city you once adored and thought unchangeable, a whole world wiped away while your life unfolded during long spells on distant paths, as happened to me during thirty years of living in semi-voluntary exile from Texas. But something always remains, the origins of your own story that can never be fully excised from the land.

Even when I lived far away, and I’ve lived as much of my life in New York City as in San Antonio, I’ve always been from Texas’s historic River City. From the first poems of my adolescence, I’ve been writing about the history, mystery, and enigma my hometown and its denizens imparted to me at my birth, like a secret compromiso, a troth with history itself. I don’t remember deciding to do that. There are few precincts of the city that don’t conjure memories of discoveries, foundings, battles, adventures, misadventures, epiphanies, close calls, amorous interludes, births, marriages, and deaths.

My city’s stories, familial and historical, just fascinated me more than anything or anywhere else. San Antonio is a crossroads of New World history, founded early in the eighteenth century, rooted in the epic of the conquest and colonization of Nueva España, transduced later into a town of the Republic of Texas, and eventually transmogrified into a city of the United States of America.

No transition was ever easy.

There’s an extraordinary but little-known map of San Antonio, designed and drawn by Eleanor Magruder in 1932 and given to me by her daughter some years ago, that testifies to this rich history. Cradled by the missions, each shown with the year of its founding, the city streets are inscribed with titles denoting what each neighborhood was known for. Hot Tamales. Mexican Hairless Dog. Burros for Sale. Cock Fight. Chile Stands. Marihuana Smoker. On Matamoros Street, a line of saucily dressed ladies bears the caption: Buenas Noches, Señor. Elsewhere, there’s the United States Arsenal and Municipal Auditorium. Also, separate cemeteries are designated as Hebrew, Catholic, Polish, and German.

Printed in a spectrum of serape colors, red, orange, green, turquoise, and brown, this cartographic gem captures for posterity the interregnum epoch of San Antonio’s past, between colonial origins in New Spain and a modern American future, the era of the city that I witnessed in its twilight.

Who knows what San Antonio might yet become?

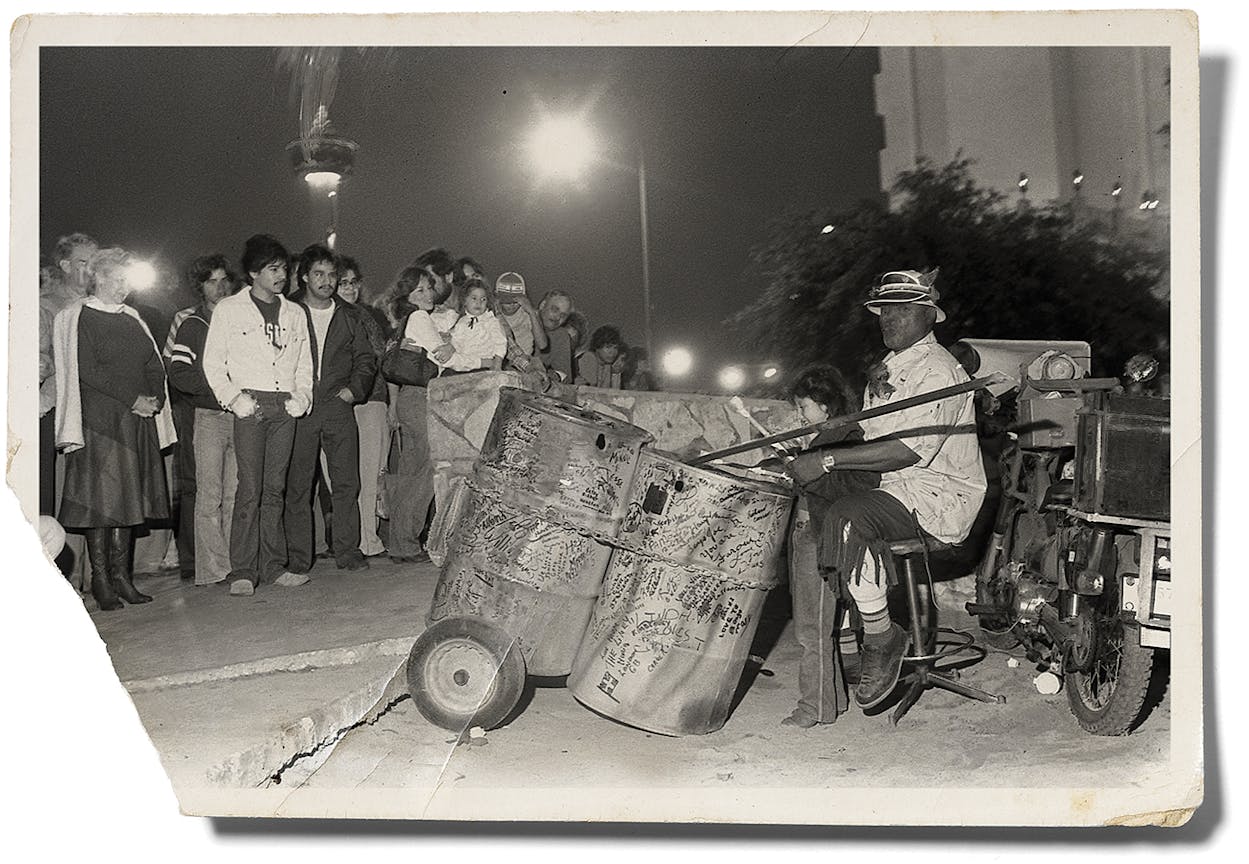

The city I discovered as a child was not the Alamo City of history books. For my twin brothers and me, the hoary limestone Alamo was where my parents would drive us many evenings, in pajamas, after the ten o’clock news, to hear the funky ruminations of Bongo Joe (a.k.a. George Coleman). San Antonio’s legendary African American street griot beat contemplative, slow-grooving, rock-steady batucadas on two battered oil drums with mallets he’d festooned with rattles that sounded as if they contained the teeth of defeated conquerors, echoing off the facade of the old Spanish mission. His drums were spray-painted in Day-Glo pink and chartreuse stripes.

As his rhythms rolled, Bongo Joe would whisper, chant, and sing tales about his dogs, his girlfriends, his journeys, his poverty and comeuppances, whistling sweet mesmerizing cadenzas in between, sometimes laughing himself silly, then finding the beat again, in the soft heat of a San Antonio night. Every now and then, you might see Bongo in daylight, warily navigating Commerce Street with his drum-laden cart, trailing a couple of dogs on leashes. He’d seem almost dejected, full of blues, not the slightly mad, ecstatic cantor he became later in the evening.

I recently saw footage of Bongo Joe shot in the early seventies by local filmmaker George Nelson. His garb was out of some jumbled imperial museum closet: combat boots with thick socks, Bermuda shorts, ruffle-breasted long-sleeved shirt with a bright-gold medallion, a red bow tie, and a tall maroon fez adorned with silver brooches that looked like Mayan glyphs. On one collar, a button read, “Kiss me, I’m Jewish.”

Eventually, Bongo Joe was moved away from the Alamo—along with his wheelbarrow, where you could leave him coins, or better, bucks—elbowed over to a noisy intersection on Commerce and Alamo streets, where we’d have to strain to hear his poesía callejera de San Anto over the bustle. Recalling Bongo Joe today, I remember how his performances left me imagining the Alamo, and San Antonio, as places where everyone, from anywhere in the world, could conjure their stories, their poetry, their rhythms, their music.

By reputation, my San Antonio wasn’t a haven of lofty literary inspiration. There were rumors that O. Henry once lived and wrote in San Antonio, that Sidney Lanier had come on a therapeutic visit seeking relief for respiratory ailments, but otherwise, San Antonio was terra incognita as far as American literary tradition was concerned. Once, there was a host of Spanish-language literary presses, some dating back to the late-eighteenth century, that had been located on a stretch of Santa Rosa Street known as Publishers Row. In addition to publishing poetry, fiction, and essays from across the Spanish-speaking world, some presses were more journalistic and political; a few even participated in the pamphleteering of the Mexican Revolution, when revolutionary Ricardo Flores Magón published his influential Regeneración journal out of San Antonio in 1904. By the late sixties most of these presses had closed, and today only La Prensa newspaper survives from that historic era.

But downtown was my literary mecca. In the former main library, on St. Mary’s Street, sitting alongside street people near windows overlooking the river, I tried to fathom Heidegger’s knotty Being and Time, or I browsed through Thomas Merton’s poetic The Geography of Lograire. I discovered William Goyen’s iridescent The House of Breath there, a memoiristic novel of rural East Texas, written in a sublime Proustian Texan English. Where Bongo Joe exalted the poetry of the city streets in vernacular, Goyen sang rustic Texas in a refined, worldly literary style. All, it seemed to me, was puro San Antonio.

And on Commerce Street, near the corner with Presa, was Brock’s Bookstore, a multistory shambles of a literary trove, resembling the remnants of a library that had been exploded in a cannonade during the Texas Revolution. Norman Brock, a Texas bibliophile, presided from behind a great oak desk, reclining his ample frame, clothed in vast, chaw-stained denim overalls, into what appeared to be a throne of musty old books.

Old man Brock was reliably cranky, a John Birch Society—leaning Texas nationalist with Confederate flags decking the old shop, so it must have taken him by surprise when Mexicans, especially young ones like me, would frequent his librería. You climbed over tumbled-down pillars of books, sidling between tall stacks where a beat-up copy of Paradise Lost might be shelved next to a dozen pristine paperbacks of Riders of the Purple Sage. But I found books there that I’d never heard of, strange volumes that changed the way I saw the world, like Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval, with its story of the celestial catastrophes that created our solar system.

To make a buy, I’d hand Mr. Brock the pile of tomes, harvested during an hour when he and I were usually the only two in the store, never saying a word to each other. He listened to country and western music on a tinny transistor radio, lost in his own reading and a cloud of cigar smoke. He had mostly gray bushy hair, with a bulldog’s mien, a bedraggled Mark Twain gone to seed. When I came up to the counter, he’d take a bead on me through dirty eyeglasses and, slowly, pull the moist, flattened cigar stub out of his mouth, rasping a hand against his unshaven jowls while he deliberated on pricing for the volumes I’d brought.

Sometimes he’d eyeball a book, toss it aside and mumble, “Ain’t for sale.” Most of the time, the price was nominal, 50 cents, $1.50, five bucks, regardless of whatever treasure you were stealing from his trove. As he worked he’d offer his own version of literary criticism.

“Dobie was a clown and a left-wing drunk!” he said of J. Frank Dobie, a friend of my grandfather Leonides’s, when I bought a copy of A Texan in England. “You wanna read about cowboys, you’re better off reading Roy Rogers, son.” Then, continuing, “Aw . . . fifty cents. You’re robbing me blind.”

Once, I found a large vintage edition of Leaves of Grass, bound in a cover of actual woven grass, dyed viridian so it would appear ever freshly cut.

“Ah, Whitman. I was looking for this copy about ten years ago. Where the hell did you find it? Now, son, he was a full homosexual and a draft dodger, so I’m not sure this is proper reading for a young person like you.”

A pause for his deep tobacco-resined baritone chortle, then: “Fifty cents.”

As he wrapped my purchases in a much-used brown-paper grocery bag, he’d toss in a few of his trademark wooden nickels, an Indian chief in profile on one side, an advertisement for the store and San Antonio on the other: “In 1968, visit the Alamo, the Tower, Hemisfair, and Brock’s Bookstore.”

And he’d usually throw in some book or two for free, a pilón as Mexicans call it. I might get an abridged edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire or Heroes of the Alamo and Their Revolutionary Ancestors, but usually it was a copy of one of his eternal favorites, in apparently inexhaustible supply, a small paperback titled Angel Unaware, about a child who died in infancy, by Dale Evans—wife of Roy Rogers.

By the time I set out from San Antonio for university, in 1975, I had already seen much of my historic city disappear. Rancho Santos was sold in 1965. Later, downtown businesses began to close, and the throngs that were once the norm well into the evening on Houston Street’s sidewalks dwindled, then vanished. Much of the town, including the old Mercado, was demolished during the period of “urban renewal,” but some of the oldest downtown businesses still exist, like Paris Hatters and Schilo’s Delicatessen; only recently, we lost the dark and sublime Esquire Bar, with a long bar that seemed to date back to the Texas Republic. For the most part, though, bankrupt and shuttered gradually became the norm. Winn’s, Frost Brothers, Joske’s all eventually closed, and the city centro grew quiet. Of course, the Alamo always remained, a stalwart memorial to the city’s fractious past, a testimony to posterity of how badly immigration policy can go awry.

When I left, I took all the rough-hewn literary formation, from Bongo Joe to old man Brock, that San Antonio had afforded, along with questions its history had left me to ponder. What was the beginning of our story? Was it with indigenous peoples settling ages ago along the river called Yanaguana? Was it Cabeza de Vaca’s rumored passage through the region in the sixteenth century? Perhaps it was the city’s christening in 1691 or its founding as a northern outpost of New Spain in 1731? And when did my own ancestors come into that long story? All of these questions smoldered within me, despite my never having had a single lesson about them in the public schools.

For me, San Antonio was always a secret Mexican city, a wary junior American metropolis, always hearkening to its rural Mexican colonial past in the memories and dreams of its silent Mexicano majority. Even though we didn’t control city politics or wield levers of power anywhere except tortillerías, cantinas, Tex-Mex cafes, and barbacoa joints, Mexicanos were a ubiquitous and abiding presence in San Antonio, a living testimony to the complex history that had given birth to our city. Being an American minority was an illusion, contradicted by our everyday lives. We were a silent, pacific, and patient insurgency, inheritors of a millennial civilization that had been taking root in these lands for hundreds of years. Many states had already come and gone. History unfolds slowly. My elders, the viejitas and viejitos, quietly watched the old world change, knowing our time would come again.

Even though our city is uniquely rooted in the two great epics of New Spain and America, people still guffaw when I talk about San Antonio’s becoming a cultural capital of the Republica Cosmica that the United States is becoming. People will come here not just to amble on the River Walk but to explore the city’s rich mestizo legacy. Instead of a battle shrine, the Alamo might even become a museum devoted to the unlimited creative possibilities of what can happen when strangers from every nation in the world meet, mingle, and make nice, just like Bongo Joe used to dream about, right there on the monument’s doorstep.

Through the decades of my exile, there were reminders of where my true home was, where the roots of my story were seemingly growing ever deeper, even while living far away. Every now and then, I’d remember meeting William Goyen in the late seventies, expecting to encounter a rugged Texan individualist writer, finding instead an urbane, fragile, and beatific longtime New Yorker, in an elegantly wrinkled white shirt and tie and seersucker suit. I remember thinking to myself, “This guy needs to get back to Texas.”

I’m no nostalgist. I returned to San Antonio in 2005 not to bask in the past but to be closer with my surviving family, and to witness, perhaps even help foster, the city’s future transformations. I’ve written about this place only to recapitulate the details of encounters between myriad peoples, not all of them related to me, to seek the serendipities that shaped the city whose imagination I inherited. Of what has been lost, nothing can be recovered, nothing reconstituted.

Following my first blind try in search of the old Rancho Santos, I paid multiple visits to the county courthouse and the county tax assessor’s office, and armed with the original deeds and present-day survey maps made my way back in April to the exact location off Old Pleasanton Road. The day I went, I met Margaret López Shope and Oscar López on some nearby land. Siblings whose family has been in the region for the past two hundred years, the two of them had only recently returned to San Antonio, a couple of years ago, after careers in the military that had taken them around the world for two decades. Using the county plat maps I’d brought, Oscar took me for a drive in his pickup into the old Santos spread. We followed eerily familiar tracks along fences shaded by great live and post oaks and brushed alongside cascading leafy grapevine. The earth was mottled with black-eyed Susans, bluebonnets, and Indian paintbrush. One giant sprawling oak at a crossroads took my breath away, conjuring weekends long ago. We drove on deeper along the sandy road.

“I’ve been all through these woods and never seen a Quonset hut,” Oscar offered, “but there are a couple of places where there are clearings, with big posts in the ground, and you kind of say to yourself, ‘What was here?’ ”