He was on fire. It was three in the morning, and most of his classmates from the Kibimba school in Burundi were dead—beaten and burned alive by friends of theirs, kids and grown-ups they had known most of their lives. Smoldering bodies lay in mounds all over the small room. He had used some of the corpses for cover, to keep from being hit by the fiery branches tossed in by the Hutu mob outside. For hours he had heard them laughing, singing, clapping, taunting. Waving their machetes, they had herded more than a hundred Tutsi teenagers and teachers from his high school into the room before sunset. A couple dozen were still alive, moaning in pain, dreaming of death.

“There weren’t that many of us left,” he says. “A guy said, ‘I’m going out—I don’t want to die like a dog.’ He jumped from a window. They cut him to pieces. Then they started a fire on the roof. After a while it started falling on me, and I held up my right arm as it came down, trying to pull bodies over me. My back and arm were on fire—it hurt so bad. I decided I had had enough. I decided to kill myself by diving from a pile of bodies onto my head. I tried twice, but it didn’t work. Then I heard a voice. It said, ‘You don’t want to die. Don’t do that.’ Outside, we could hear Hutus giving up and leaving. I heard one say, ‘Before we go, let’s make sure everyone is dead.’ So three came inside. One put a spear through a guy’s heart; another guy tried to escape, and they caught him and killed him. I heard the voice say, ‘Get out.’ There was a body next to me, burned down to the bones. It was hot. I grabbed a bone—it was hot in my hands—and used it to break the bar on the window. The fires had been going for nine hours, so it was easy to break. My thinking was, I wanted to kill myself. I wanted to be identifiable. I wanted my parents to know me. I didn’t want to be all burned up, like everyone else. I was jumping to let them kill me.”

There was a fire underneath the window, set as an obstacle to escape. He jumped. And somehow, in the darkness, amid the uproar of genocide, at least for a few seconds, no one saw him. His back was on fire, his legs were smoking, and his feet were raw with pain. He ran. If you could call it running.

Gilbert!” Almost a decade later, on March 30, 2003, he crossed the finish line at the Capitol 10,000 in Austin to the sound of hundreds of people clapping, many calling his name. “Gilbert! Woo!” He finished ahead of some 14,000 runners, but it wasn’t good enough, and the look on his face said that he knew it. Others knew it too. A woman off to the side yelled, “Coach, you’re awesome! I love you! You’re number one, Gilbert!” In fact, Gilbert Tuhabonye was number three, a minute and fifteen seconds behind the winner in a race he had won the previous year and was favored to win again. Gilbert turned and jogged back against the flow of the other finishers, shaking hands and high-fiving spectators, who all seemed to know the thin African. Then he ran the last fifty yards again with Richard Mendez, one of many runners he had trained. “Come on! Come on!” Gilbert said to Mendez. “High knee!” When Mendez finished, Gilbert went back and ran with Ryan Steglich, another of his charges. And then with Shae Rainer and Lisa Spenner. “Come on! Come on!” he yelled. “Butt kick!”

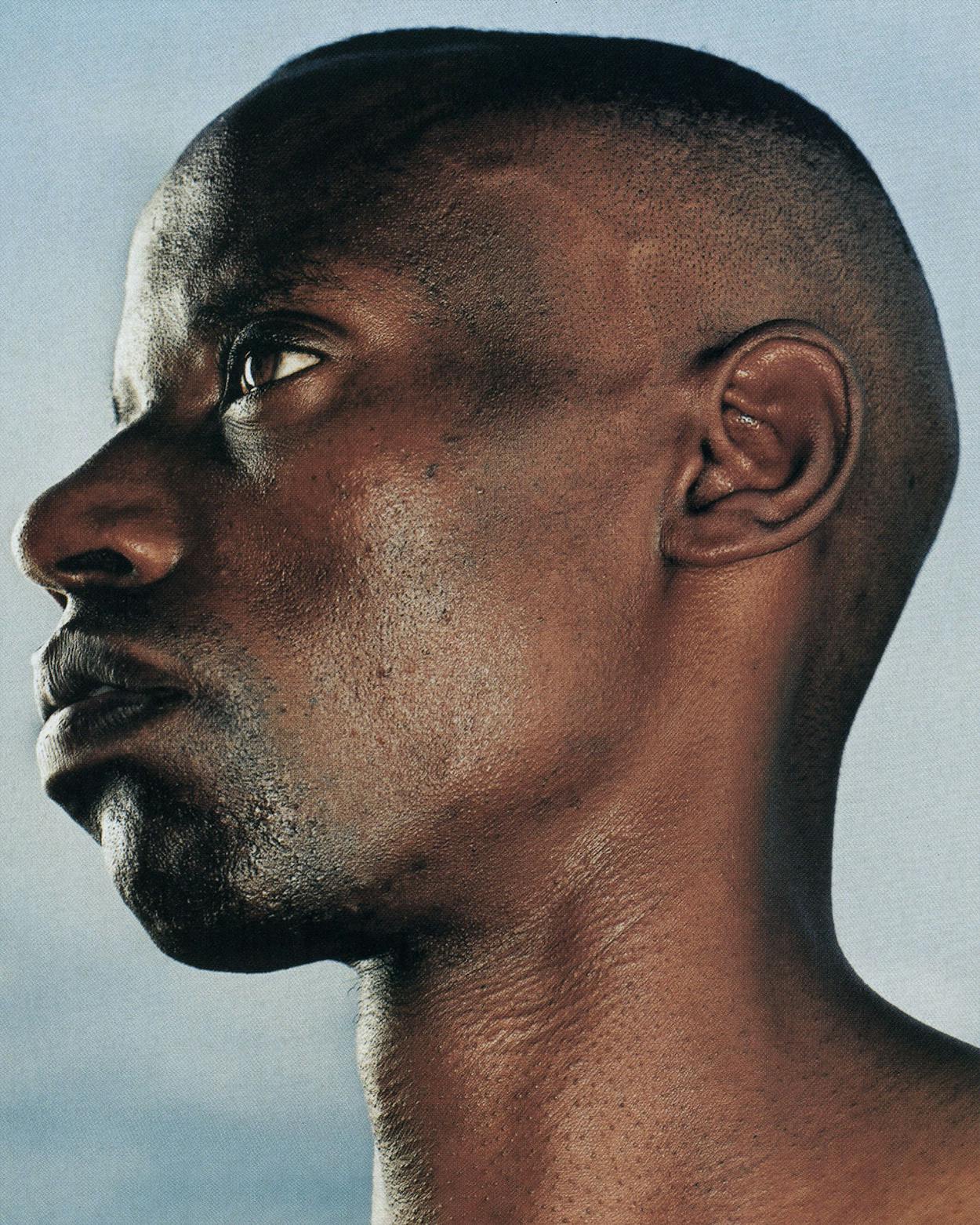

Afterward, Gilbert, who stands five feet ten and weighs 127 pounds, hung around talking to the other runners, many of whom wore T-shirts that read “Gilbert’s Gazelles Training Group.” A circle of eight stood basking in his approval, trading anecdotes about their pains and agonies, as runners do. He laughed and joked with them, accepting halfhearted high fives and thin encouragement, which made him look down self-consciously. Eight thousand miles from home, he’s a celebrity in Austin, a 28-year-old with protruding teeth and a boyish laugh, the most popular running coach in a town of rabid runners, a former national champion, both as a teenager in Africa and as a college student in West Texas. Governor Rick Perry, himself an avid runner, seeks out Gilbert to chat. Kids ask for his autograph. Rich white ladies pay him to order them to run laps. Everybody wants him to make them go faster. They’ve heard his mantra: It’s all about form. “If you have good form,” says Gilbert, “running becomes a joy. You can go farther and faster. You can run forever.”

You can run forever. This, to a runner, is heaven. Gilbert’s students see him as a savior, upbeat after all that he’s been through, relentless and optimistic when he has every right to be withdrawn and angry. A man on a mission: to win an Olympic medal, to tell his story, to show the world what one tribe did and what one man—set on fire and left to die—can do. A man with a last name (pronounced “Too-ha-bon-yay”) almost too good to be true. “In Burundi,” Gilbert says, “your last name has to have meaning. When I was born, it was a very difficult time. It was right after the war. There had been a big drought, crickets attacked the crops—and then my mother broke her ankle. When I was born, she said I was special. She said, ‘This is not my son. This is a son of God.’ ‘Tuhabonye’ means ‘a son of God.'”

As the runners dispersed, Jeff Kloster, who works with Gilbert at RunTex, an Austin running store, brought him his warm-ups, and Gilbert took off his shirt to change. Though Jeff had seen them before, he could not take his eyes off the scars that cover Gilbert’s back. The burns continue along his right arm, where they bubble the skin like large patches of candle wax, and then to his right leg, which gets darker along the sides of his calf, where the flames ate down to the bone. The scars are proof of the unthinkable: Ten years ago, on a mountaintop in Burundi, high school kids and their teachers were stuck in a room and set on fire. For nine hours Gilbert watched his friends die, breathed their burning flesh, hid under their corpses. Then he ran for his life. People speak of crucibles and the forging of character. They have no idea.

In the living room of his two-bedroom South Austin apartment, Gilbert is beating on an imaginary drum. He’s playing along with a group of drummers on a CD of Burundian music. It sounds like an army—pounding, lurching, exploding, simmering, then accelerating beats; there’s no melody, only occasional yelling and chanting. “There are eleven people in a circle,” he says excitedly, “each with a three-foot-wide drum.” He moves his arms and his head along with the rhythm. “There’s one in the center. He’s calling out, jumping. Everyone is watching him, following him. There’s a lot of dancing. It’s awesome.”

Gilbert’s pretty wife, Triphine, plays nearby with their daughter, Emma. At home the couple speak mostly Kirundi, their native tongue, though they try to speak English around Emma, an alternately shy and boisterous two-year-old. Gilbert also speaks French and Swahili. His English is very good, and he speaks it with a melodious lilt. He has short hair and high cheekbones—he’s handsome in an earnest, youthful way. He’s wearing blue denim shorts, a gray Mizuno shirt, and sandals. His legs are thin but muscular. His burns look like relief maps.

The apartment is cluttered with Emma’s toys. On the walls are a tacked-up Burundi flag and photos of Gilbert running; a Bible sits on a table. Another song comes on, from the sixties, called “Yes, I Love Micombero,” about a Tutsi president from back then. Gilbert sings along, and Triph, who is also a Tutsi, remembers it too. “If you say this guy’s name in front of a Hutu,” says Gilbert, “he will kill you.” Gilbert pretends to play some of the other instruments. “In Burundi, the music is good and the climate is beautiful. If there was peace, I’d go there to train. The lake is gorgeous—there are hundreds of types of fish. It’s like Hawaii: a lot of birds, all these types of fruits. It’s paradise.”

Burundi is a small, poor, mountainous country in east central Africa. Gilbert was born in the southern county of Songa on November 22, 1974, the third of four children. His Tutsi parents were farmers, raising corn, potatoes, peas, and beans, and also kept milk cows. As a boy, he ran everywhere: down the valley to get water, to school five miles away. He loved to race his friends, but more than anything else, he loved to chase the family’s cows. In the sixth grade, he was baptized a Catholic, and the next year he went to a Protestant boarding school in Kibimba, about 150 miles away. Of the thousand or so students, about 60 percent were Hutus and the rest Tutsis. For the most part, they got along pretty well, sharing the same dorms and playing on the same soccer team.

Though the Hutu and Tutsi tribes have squabbled for centuries, it’s only in the past two generations that things have gotten brutal, both in Burundi and in its northern neighbor, Rwanda. The countries are roughly the same size and are similar in many ways (think of the Dakotas). They each have a five-to-one mix of Hutus and Tutsis, they speak Kirundi, they’re roughly two-thirds Catholic, and they have shared histories. In Burundi, the Tutsis (a.k.a. the Watusi) have ruled the Hutus ever since emigrating from Ethiopia, more than five hundred years ago. The Tutsis were cattle herders and aristocrats, while the Hutus were working-class farmers. They lived together in relative peace until the Europeans came; Burundi and Rwanda were incorporated into German East Africa in the 1890’s, and Belgium took over after World War I. “During colonization, they started dividing people,” says Gilbert. “The Germans made the differences between Tutsi and Hutu into law: Divide and govern.”

Both Rwanda and Burundi became independent in 1962. While the Hutus gained some power in Rwanda, Tutsis controlled the army and the government in Burundi, making occasional attempts at parliamentary elections to give the more numerous Hutus a voice in government. Just before and after independence, ethnic violence flared up, and there were massacres by both sides. In 1972 an attempted coup in Burundi led to the slaughter of some 150,000 Hutus; many Tutsis were killed too, including three of Gilbert’s uncles. “Bad teaching,” he says about the causes of the violence. “Deep hate.” It’s a class thing and a race thing, even though both tribes have intermingled for so long that sometimes even Burundians can’t tell the difference. But usually they can. A Tutsi, says Gilbert, tends to be tall and thin, with a narrow nose; a Hutu is shorter, more muscular, and has a wider nose. Tutsis complain that Hutus lack ambition; Hutus say Tutsis are arrogant.

At the Kibimba school, Gilbert began running competitively. As a freshman, he won an 8K race running barefoot. The next year, he met a coach who showed him how to run properly—how to get his knees up and how to hold his arms. The coach told Gilbert that if he worked hard, he could make the Olympics. In his junior year, Gilbert was a national champion in the 400 and 800 meters, already a great runner in a country known for producing them. By his senior year, in 1993, all he cared about was school and running. His goal was to get a scholarship to an American college, get an education, and return home. The dream actually seemed possible, since Burundi appeared to have turned a corner on its violent past: The latest Tutsi dictator had mandated the first-ever presidential election, and not surprisingly, a Hutu won. A new day was dawning in Burundi. Four months after the election, though, the president was assassinated by Tutsi soldiers. It was a new day, all right.

The night before,” says Gilbert, “I didn’t sleep. I had two tests that day, in chemistry and biology. I was thinking, maybe I studied too hard. It was my senior year, and I had to be prepared for college. That morning I turned on the radio. Nothing. I thought the battery was dead. I went to class, and people started talking about the rumors—usually when the radio isn’t working, it’s a coup. A friend said there was a putsch, that the president was dead. There weren’t many Hutus around, but I saw one, my teammate on the 440 relay. He showed me a machete, pulled it out of its sheath, ran it along his throat, and said, ‘Tonight is the night I’m gonna cut your neck.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because you guys killed our president.’ I thought he was joking. I found out later that Hutus had been gathering since three in the morning, planning on killing Tutsis. By ten, a mob had gathered at the school—Hutus with machetes. They took away a Tutsi professor and said, ‘We’re gonna kill all these Tutsis.’ I told a professor, a Tutsi, what people were saying. He said, ‘Don’t worry—they can’t do that.'”

Sitting on his flowery couch, Gilbert recounts this story carefully, speaking slowly at some points and excitedly at others, sometimes waving his arms. “Around noon, we went to the principal to ask for help, and he told us, ‘You killed the president, and you have to die.’ We tried to organize a peaceful running away. We also hoped the army would come. There were hundreds of us marching—girls, boys, teachers, farmers—and we locked our arms together. We didn’t get far; the mob stopped us. By then it had started raining. Everywhere we looked, there was a Hutu with a machete, a bow and arrow, or a spear. Some were my friends. They told us to go back to the school. We didn’t move. All of a sudden, a woman took a spear and threw it into the crowd. And they attacked us—cutting people, their ears and noses, so they’d know who was a Tutsi.

“Many escaped. I tried to, but they were watching me. They knew I was a cross-country runner, that I could run and tell the soldiers. They got me, and the principal said I’d be the last to die. He said they’d do me like they did Jesus Christ. He said, ‘You will see what Jesus saw on the cross.’ He meant I was going to get a good torture, like Jesus got. They attached us to each other, one by one, with a rope, by the arms. I said, ‘Where are you taking us? I thought we were friends.’ ‘Not anymore.’

“Kids were bleeding, screaming, crying. My heart was beating like I don’t know what, I was so scared. They took us down the hill to a highway gas station owned by a Hutu, a guy I knew—I bought stuff from him all the time. People were all around us, walking next to us, with machetes. They were singing, ‘We caught the enemy! We’re gonna burn them to death!’ When we got there, they took our clothes. All I had on was underwear and a shirt. Before they pushed us inside, they beat every kid on the back of the neck with a big club. They hit hard—to stun or paralyze. Some were killed. I was one of the last ones and jumped inside, but they beat me on the chest so hard that I bled for three weeks.

“There were more than a hundred people in a room this big”—Gilbert points to the kitchen wall on the far side of his living room, a 40- by 25-foot space. “We couldn’t move. It was jammed with half-naked people screaming and crying. Outside, they were dancing, clapping, singing, ‘We did it!’ Just after I got in, they poured gasoline in through the windows—everyone got some on them. I got it on my shirt, so I took it off. Then they threw in branches that were on fire. The flames moved so fast. People were trying to hide and put out the flames. It was horrible. Many were killed by the fire and smoke. The Hutus were waiting outside for us to try to escape, but the doors were thick and we couldn’t break out.

“Because I was one of the last in, I was near the wall, banging against it, and I found a door to a kind of closet. I pushed it open, and there were more people in there. I let a few more inside. The Hutus kept throwing lit branches in through a window. I hid under the bodies of my friends. After a couple more hours, I heard a student tell the chemistry professor to get some chemicals to throw inside. The people left were gasping for air. I took a deep breath and was pushing air away from my face.”

At this point, the Hutus set fire to the roof, Gilbert caught fire, and he decided to let them kill him. “But something was guiding me,” he says. “When I jumped, they were outside, just a few feet away, standing by the fire they’d built under the window. But they didn’t see me. As soon as I landed, I couldn’t see clearly. The wind was blowing, and it was cold—I was naked. I just started moving and got around the corner. I heard someone shout, ‘Gilbert is coming!’ I saw a mob of people—they stood up, holding machetes. Everywhere, I saw people coming. I ran downhill. The more I ran, the wind was teasing the fire on my back. Some people were saying, ‘Don’t worry about him; he’s gonna die anyway,’ and they gave up. But not everyone. A guy came running at me with a machete. I ducked, and he just missed me and cut his own arm. I kept running, and all of a sudden I fell into a deep ditch filled with rainwater. It put out the fire on my back. I heard people talking, saying, ‘Let’s catch him. He knows who we are.’ I heard this one guy coming—I knew his voice—and he fell into the ditch. I was leaning against the side, and he had a spear in one hand and a machete in the other. I killed him. I have never confessed this before. I was so angry. They had burned me, killed my friends. I had nothing to lose. But I don’t think it was me who got that strength. God gives power to eliminate evil.”

How exactly did a mild-mannered high school kid kill a man? Gilbert demonstrates—he puts one hand on his chin and the other on the back of his head, jerking and twisting hard, pantomiming the breaking of someone’s neck. “I watch Chuck Norris,” he says. “Chuck Norris was my favorite. The guy puked on himself, and I knew he was dead.”

“The voice in my head said, ‘Go away,'” Gilbert continues, “so I got up again. I was so thirsty, so dehydrated, and I started toward the hospital, about a half mile away. It was so hard to move; every step hurt. I could barely stand up. My feet, I could see, were like meat. My right leg was so bad that I could see the bone. I was on my hands and knees, running like a monkey. There were still Hutus everywhere with machetes. The voice was telling me, ‘You don’t want to die.’ My heart was beating so hard that I thought they could hear it. When I got to the hospital, a guy saw me going in and said, ‘He runs like a monkey. He’s not a human being. He’s a spirit.'”

It was all about form—the years on the track, keeping his knees up and his arms back, pushing himself when he thought he was going to die. He stumbled into the sanctuary of the hospital. Soon the soldiers came, and Gilbert, with third-degree burns over 30 percent of his body, was moved to an army hospital; later he recovered in a hospital near his home, where his mother came to visit him. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, she and Gilbert’s father had been told that he was dead. Then, later that night, Gilbert’s father had been murdered by a Hutu gang on the road. Now, she was told, her son was alive.

“When my mother came to the hospital, I was bandaged everywhere. She said, ‘I told you, you are a son of God. If it wasn’t for God, you are dead.’ It’s a shock and also a lesson. It has meaning. I don’t think I survived because I’m strong but because of the power of God. God showed up.” But what about the others? Surely they were also children of God. Why weren’t they spared as well? “That’s the thing I didn’t understand. Afterward, I asked myself, ‘Why me? Why did I survive?'”

In the hospital, he lay on his stomach and left side, pondering the unknowable. When he closed his eyes to sleep, he saw flames and heard screams. He read his Bible. He figured the voice he had heard was God’s, but he didn’t know why it had spoken only to him. “Why did God want me to survive?”

Why do people run—that is, people who aren’t being chased by a fire-throwing, machete-waving mob? Why do thousands get up early on a Sunday morning and put their knees and ankles and hearts and lungs through the hell of 10,000 meters on hard pavement?

There is no single good answer to this question. In high school, people run for glory or for girls (or boys). Maybe they’re being punished. Later on, they run for exercise or just to fit into their pants. Eventually, if they’re lucky, they tap into another world: the state of physical and mental grace they reach when they’re cruising, when their blood is racing through their every vein. Their thoughts have never been clearer, and their limbs are snapping in rhythm; their souls are revealed, and they are striving, excellent souls. They become obsessed with this feeling. They get religious about it. It is, for some of them, as spiritual as they will ever get.

Go to a running trail in any big city in Texas, and you will see them working toward this feeling: the grimacer, the puffer, the hacker, the wheezer; the stiff-armed and the backward-leaning; the torso-barely-moving and the stumpy-legs-moving-fast; the potato on sticks, the pear-shaped, the ham-thighed; the loping underachiever and the determined overstepper; the elbows swiveling, the shoulders hunched, the whole body moving as if underwater. They are all bound together by this transforming passion and perhaps also by the fact that they look less silly if they run in numbers. They are, most of them, loners: mild-mannered, nervous, self-conscious, preoccupied with their bodies. They long to get better and faster, to raise their personal bests, even when at a certain point that becomes physically impossible (such logic does not concern the runner, who is high on the opiate of self-improvement). Their feet splay to the sides, their arms flail. They are desperate.

And in Austin, at least, they hang on Gilbert’s every word. He coaches at RunTex, where he is one of twenty instructors—”the Michael Jordan” of the bunch, says the store’s owner, Paul Carrozza. Some of Gilbert’s students (he has about a hundred at any one time) are competitive runners, people who, say, have qualified for the Boston Marathon and want to set a personal record. They’re fanatics, obsessed with every half-second, every curve of the trail, every ache and pain. They aspire to the elite. Lisa Spenner, 28, is one of these, a former triathlete who, after training with Gilbert for the Motorola Marathon, missed qualifying for the American Olympic trials by only 51 seconds. Most of Gilbert’s students are athletic types, late bloomers who run regularly but perhaps unwisely in local races like the Capitol 10K. They don’t aspire to the elite; they just want to run faster. Then there are the ones who just want to get some exercise with the enthusiastic African man. They aspire to look good.

Gilbert’s methods are pretty simple, really. One of the pleasant paradoxes of running is that the more machinelike you get, the freer you feel. As he says, it’s all about form: how the arms move (economically, if possible) and the feet land (heel to toe). His workouts are intense—sprinting around the track, speeding up hills, springing up and down on a bench—all to improve the basic mechanics of movement. He pushes his students hard and yells at them melodramatically as he trots alongside (“Knees up! Knees up! Knees up! I want to see you in the air!”). When, after eight successive sprints around the track or three inexorable ascents up a steep hill or a series of 100-yard dashes on a single breath of air, they feel like they’re about to die, they look at Gilbert’s scars. How bad, really, could it be? “He gets people to believe in themselves,” says Spenner. “He treats everyone like they’re amazing.” Sometimes they watch him as he motors like a quiet machine, his head barely bobbing, his arms swinging in perfect time, his feet making quiet patting sounds, and then they try it themselves. At the end of a workout they’re breathing hard, bent over, walking slowly, wet with sweat, exhausted. They are in agony. They are happy. They are better.

“Most elite runners think it’s all about them,” says Carrozza. “Gilbert is so giving, so willing to coach others.” If Gilbert is their savior, they are his saviors too—or at least they help answer the question that has haunted him for a decade now: Why me? “Eventually, I realized I had to help people,” he says, “coaching them, telling them my story, telling what happened. When I help people, I feel good.”

The Kibimba massacre was the beginning of a bloody civil war in which there were mass killings fueled by revenge on both sides. Six months later, a plane carrying the president of Rwanda and the new leader of Burundi was shot down, leading to the genocide in Rwanda of 800,000 Tutsis over a period of one hundred days; there hadn’t been such an efficient killing machine since the Holocaust. Burundi was lucky—the Hutus weren’t as organized there, and the Tutsis controlled the army. A mere 200,000, mostly Hutus, would die throughout the rest of the nineties.

Gilbert spent three months in the hospital, recovering not only from the burns but from the savage beating he had received. He was now a witness, for God and Tutsi, and he told his story to anyone who visited. His right leg was so badly burned that his knee was stuck at a 90-degree angle. The doctor said it would take six months to heal. Frustrated, Gilbert got on a bike and forcibly unstuck it. “The blood came through; I could sleep again. If I hadn’t done it, I could have been crippled.” While in the hospital, he got a scholarship offer from Tulane University, in New Orleans. Gilbert wasn’t healed enough yet to accept it, but he used it as motivation to run again. The biking led to walking, which led to jogging, which finally led to running a year after he had been left to die. In 1995 he ran the 400 meters at a competition in Kenya and later that year ran for Burundi in the World University Games in Japan. He went to the University of Burundi for a year and was training for the 1996 Olympics when he was sent to an Olympic training center in Georgia, one of many such facilities established by the International Olympic Committee for athletes of developing nations. He ended up as an alternate on the team but stayed in Georgia, taking English classes at La Grange College.

The next year, he accepted a track scholarship from Abilene Christian University, the small Church of Christ school in West Texas that has a storied running history. ACU has won 49 NCAA Division II track-and-field championships and has sent almost three dozen athletes to the Olympics, including the great Bobby Morrow, who, as a sophomore, won the 100-meter and 200-meter dashes and the 400-meter relay at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. ACU has recently been home to many African runners, and it was a perfect place for Gilbert, who studied agricultural business and starred for the team. He was an all-American all three years at ACU, running the 800 and 1,500 meters, the 8K and 10K, and the mile, and he was part of seven national championship teams, winning the 800 indoors in 1999. Coach Jon Murray says Gilbert was a natural team leader. “We called him the Ambassador,” he recalls. “He was always making friends, always helping people.”

Gilbert liked Abilene. “It gave me time to worship and think,” he says. “No distractions.” He told his story to church and school groups, and eventually a Burundian student from North Texas State University in Denton visited and wrote about him for her school paper. CNN did a story on him too. In 1999 he won an award given to courageous student athletes. He got to meet Bill Clinton and Muhammad Ali. In 2000 his girlfriend, Triph, whom he had met in the hospital, came to America and enrolled at ACU, and they were married soon after.

After graduation, Gilbert couldn’t find work, so one of his professors called an old ACU roommate in Austin: Paul Carrozza, who invited Gilbert down to visit. Inspired by his story, Carrozza offered him a position—several, actually. He wouldn’t just sell shoes; he would speak to kids as part of the Marathon Kids program, trying to get them to run. And he’d race. Carrozza, a former track star himself at ACU, would coach him. It was a long way from the killing fields of Burundi.

He’s gone back only once—Christmas of 1999—and he learned a hard lesson: You can go home again, but you really shouldn’t if you were a witness to genocide who’s told your story on CNN. The local media found him, and relatives told him that Hutus were looking for him. Gilbert lay low and fled for good just after New Year’s. “I’ll never go back,” he says. He doesn’t trust the recent power-sharing arrangement that calls for a Tutsi and a Hutu to alternate as president every eighteen months. “If there’s a Hutu in power,” he says, “there’s no Tutsi who could sleep at night.” Gilbert was granted political asylum in the U.S. in 2001, and he’s trying to get permanent residency.

We’re accustomed to African American athletes being superior, and we’re accustomed to Africans, especially East Africans, being the best long-distance runners. Generally, they are. But they’re human. They make mistakes. They get hypothermia, as Gilbert did in February at the Motorola Marathon in Austin, when he finished with a disappointing time of 2:26. They train wrong, as Gilbert did for the Capitol 10,000. They get tired. On a typical day, Gilbert is up at five, coaching at six, doing a morning run by seven-thirty, selling shoes all day, coaching after work, and then doing an evening run by seven; he runs an average of twenty miles a day. He tries to give time to Triph and Emma. He almost always falls short.

And, as unbelievable as it may seem to his students, sometimes he doubts himself. “I’ve never seen a guy so easily psyched out,” says John Conley, Gilbert’s agent. “Before a race, I tell him he’s done the work; he knows the strategy; he’s got the speed; he’s got the strength. He just has to not let the negative talk in his head get to him. It’s his Achilles’ heel. He thinks, ‘These guys are better than me,’ and he puts himself in last place. If he could be like Ali and think, ‘I’m the greatest,’ he’d be unbeatable.”

In truth, runners don’t race to beat other runners. They race against themselves: to conquer their wills, to transcend their weaknesses, to beat back their nightmares. Of course, a runner will never actually beat himself; he’ll never be good enough to do that. But he can get better. And so Gilbert has spent the spring and summer of this year trying to do just that, racing men who are faster than he is, knowing that this makes him better. In May he went to Indianapolis to run a half-marathon against a fast field and finished tenth, with a respectable time of 1:07:50. In June he ran the prestigious Grandma’s Marathon in Duluth, Minnesota, at 2:23, but he’ll need to get under 2:20 to make the Burundi Olympic team. Carrozza wants to push him even further and have him train with even faster runners. One problem, according to Carrozza, is that Gilbert has been running at slower paces with his students, essentially dumbing his body down. “He’s got to refocus on himself,” says Carrozza, “to balance the coaching with his training. But he doesn’t have to give up coaching.”

That will be a relief to the Gazelles and the spud-shaped obsessives on the running trails. Of course, they see Gilbert as more than just a good coach. He’s a flesh-and-blood symbol, a real-life survivor, a true son of God, a man on a mission that’s both infinitely greater than and remarkably similar to their own: the daily struggle to show what you’re made of.