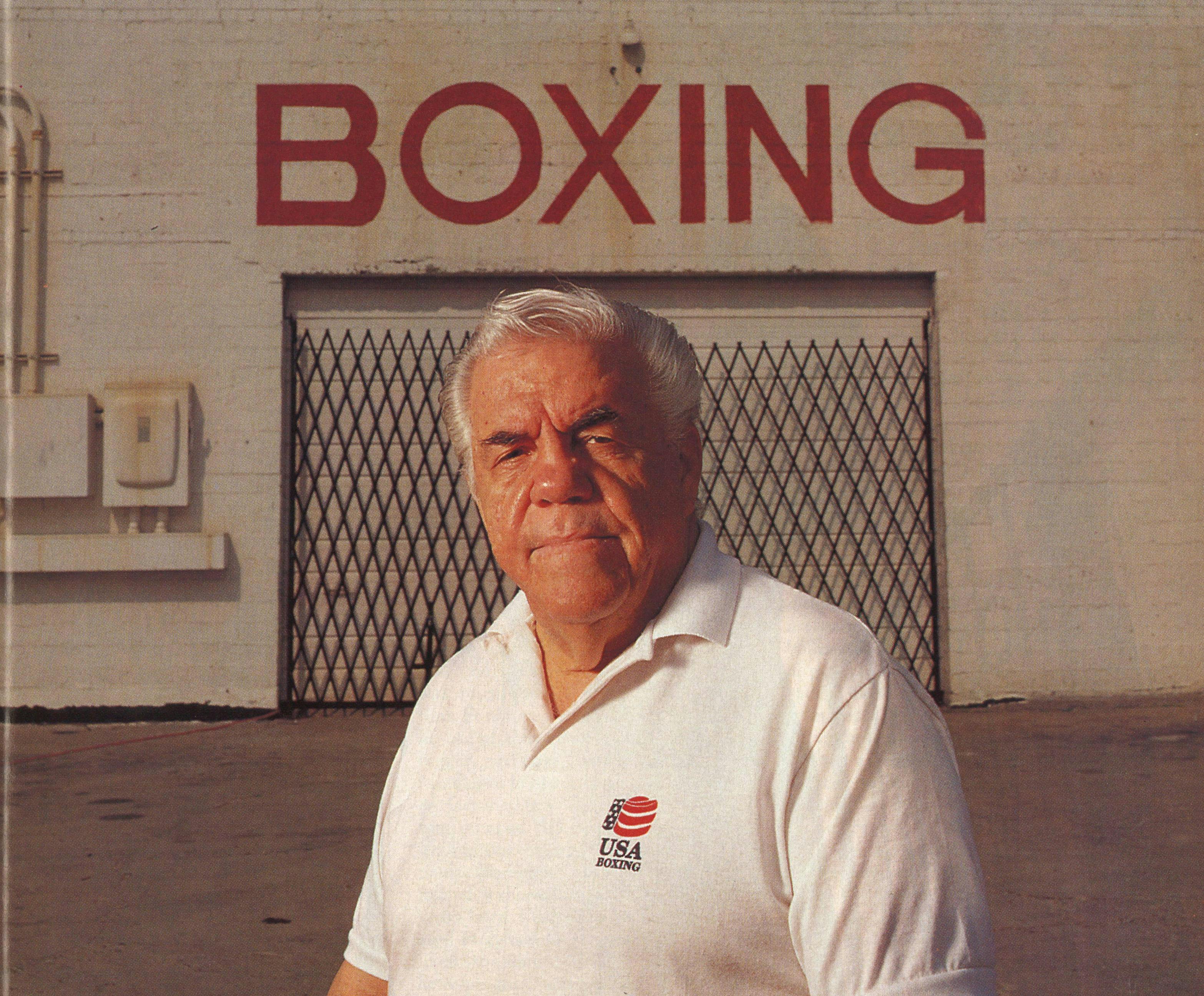

In early March, when Evander Holyfield began training to defend his title against George Foreman, visitors came to the gym in north Houston in trickles, sometimes in expensive cars that looked out of place in the neighborhood, especially in daylight. Some brought their own photographers. They wore three-piece suits, shiny Italian-made shoes, and excessive jewelry, and when they posed with the heavyweight champion of the world, they smiled as though this were a birthday party. They huddled for a while in the back of the gym with Lou Duva, the stubby, pugnacious onetime teamsters union boss who controls Holyfield and thirteen other current or former world champions, and ten minutes later, they were gone.

By the time Duva opened the doubledoor entrance of the Heights Boxing Gym each morning at ten o’clock, there were people waiting to do business, not all of it related to the championship fight in Atlantic City on April 19. The sweet science of boxing had always attracted more hornets than honeybees. Drummers and hustlers of every variety came around, paying their respects to Duva, shaking hands with the champ, slipping their cards into the coat pockets of reporters. Firemen from a neighborhood station stopped by some mornings, and so did youngsters from a local boxing association. One morning the only spectators were a pair of ladies in generous makeup and Frederick’s of Hollywood evening wear, their oversized shades suggesting that it had been a while since they had seen the sun.

Holyfield seldom arrived before ten-thirty or eleven, and there were days when he didn’t arrive at all. While his handlers waited, they worked with other boxers in Duva’s Main Events boxing stable. The best was Raoul Marquez, an eighteen-year-old Houston middleweight, a good bet to win an Olympic gold medal next year and maybe a world professional championship a few years after that. There were usually a few broken-down fighters hanging around the gym, too, looking for a job or just a kind word. Al Evans, a tall, angular black man with a creased face and gentle eyes, came in with his four-year-old son, DaVan, telling anyone who would listen that he was searching for a filmmaker to document his career “and show the way Jesus helped me.” Evans’ single claim to fame was that eight years ago, in an amateur fight, he knocked out Mike Tyson. Evans became such a familiar figure around the gym that Duva finally put him to work doing odd jobs.

Holyfield liked training in Houston—he had even bought a condominium here—partly because he had got it in his head that Houston’s heat and humidity helped him round into shape, but also because he associated his hometown of Atlanta with losers. Another reason was that Holyfield’s conditioning coach, Tim Hallmark, lived here. Holyfield and Hallmark went back to 1986, when Holyfield was training for one of the last fifteen-round title fights on record. When they changed the rules of boxing to set the maximum limit at twelve, the sweet science lost more than just three rounds.

The Heights Boxing Gym was near the intersection of Heights and Washington, so close to downtown that you could see the skyline. Forty or fifty years ago, this neighborhood was white, middle class, and residential, but the homes were long gone and in their place were endless blocks of used-car lots, auto repair shops, pawnshops, fast-food places, and black jazz clubs. The gym sat off the main drag, at the rear of Sam Segari’s trendy restaurant and bar and in back of a parking lot used by Rockefeller’s, one of the city’s livelier night spots.

The gym was excessively modest, a white concrete-block structure just large enough to accommodate a ring, an exercise area, and a simple dressing room with no shower. Two heavy bags hung from chains, but there were no speed bags—this despite the fact that early in his career Holyfield was obsessed with them. As an eight-year-old at a boys’ club in Atlanta, Holyfield began boxing not because he liked to hit people or mix it up but because he fell in love with the rat-tat-tat-bang of the light bag. A row of mirrors covered part of one wall, reflecting a platform for rope skipping and a bench for weightlifting or stretching. Except for those spare furnishings, the only equipment was what Holyfield’s entourage brought each morning.

This was the biggest fight in Lou Duva’s fifty years in the game, bigger even than the one last October when Holyfield lifted the championship from an overweight and undermotivated Buster Douglas. Duva said that he knew that his man would knock out Douglas because Douglas had quit in three of his last four fights: His upset of Tyson was one of those aberrations that mainly served to remind the public that the sweet science is sustained by periodic mutations. Duva had grown up on the streets of New York’s Little Italy and in Paterson, New Jersey. He got his start in boxing as a bucket carrier at the legendary Stillman’s Gym—the University of Eighth Avenue, the great boxing writer A. J. Liebling called it. While other students of the game were studying the fighters, Duva studied the old-time managers, noting how they maneuvered to steal fights. He had been a trucker, a bail bondsman, a bounty hunter, a union boss, a club-fight manager, and eventually a millionaire—but the one thing Duva had never done until now was own (as they used to say) a heavyweight champion. He who controls the heavyweight championship controls everything.

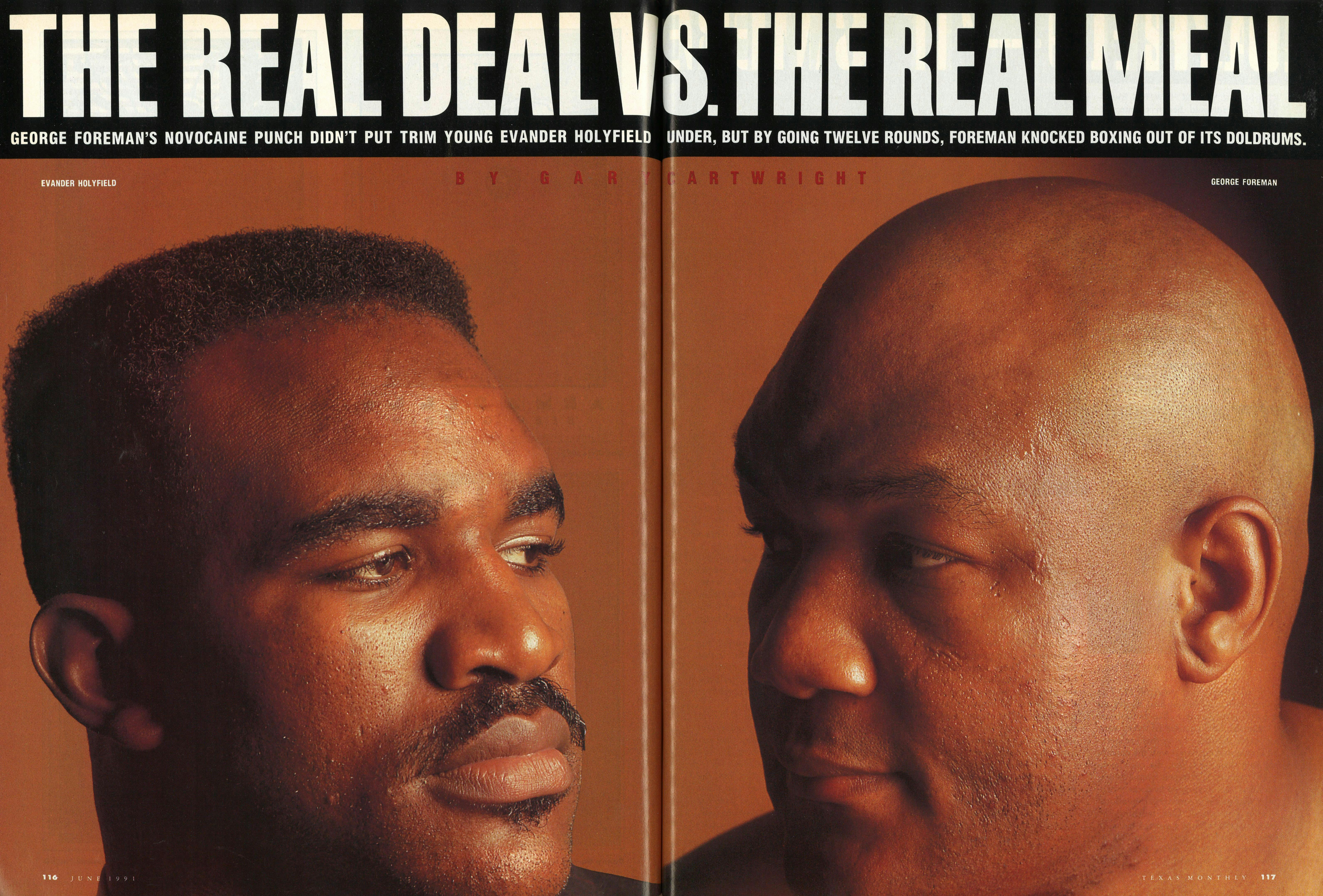

Holyfield was Lou Duva’s starry crown. Risking it against a 42-year-old phenomenon like George Foreman was a way to ensure a payday of, let us say, $100 million when the Holyfield-Tyson fight was arranged maybe a year from now. That would have to wait, of course, until Holyfield beat Foreman … if he beat Foreman. Sure, Foreman was much older than Holyfield: By the time Foreman was 28, Holyfield’s age, he had already retired. But he was also bigger, stronger, wiser, and meaner. No fighter in history ever punched harder. Getting hit by Foreman was like getting pumped full of Novocain. Jimmy Young, one of only two boxers ever to defeat Foreman, still remembered the jolt of a Foreman left hook fourteen years later. Foreman’s reputation bothered Holyfield more than the champion liked to admit. When former light- heavyweight champion Jose Torres visited Holyfield’s camp, he sensed that Holyfield was nervous and apprehensive. If Torres smelled fear, Duva must have smelled it, too. During the third week of training, Duva ordered red-and-gold banners suspended from the rafters, reminding visitors—Holyfield—that the fighter was the “undisputed” heavyweight champion of the world, that he was “the real deal,” that “youth beats age.”

No Rolls-Royce had ever been treated better than Duva treated his man Holyfield. The gruff, pint-size manager had assembled a team of specialists to watch over the champion from the time he awoke until he went to bed. At the head of the team was trainer George Benton, who had been Joe Frazier’s co-trainer in the second Frazier-Foreman fight, but Holyfield also worked daily with his conditioning coach, Hallmark, and with an assistant trainer, a weight coach, and a ballet instructor. The champ’s nutritional program was closely monitored, and special exercise equipment was designed to increase his punching power. Instead of traditional roadwork, he ran wind sprints, a method of rehearsing his body to work without oxygen, as it would be required to do at the finish of a hard round. Holyfield spent his mornings in the gym, his afternoons watching film and resting, and his evenings in a health spa in the Galleria area. His only diversion was a Thursday-night ritual in which Duva treated the entire team to an evening of Italian food and bowling.

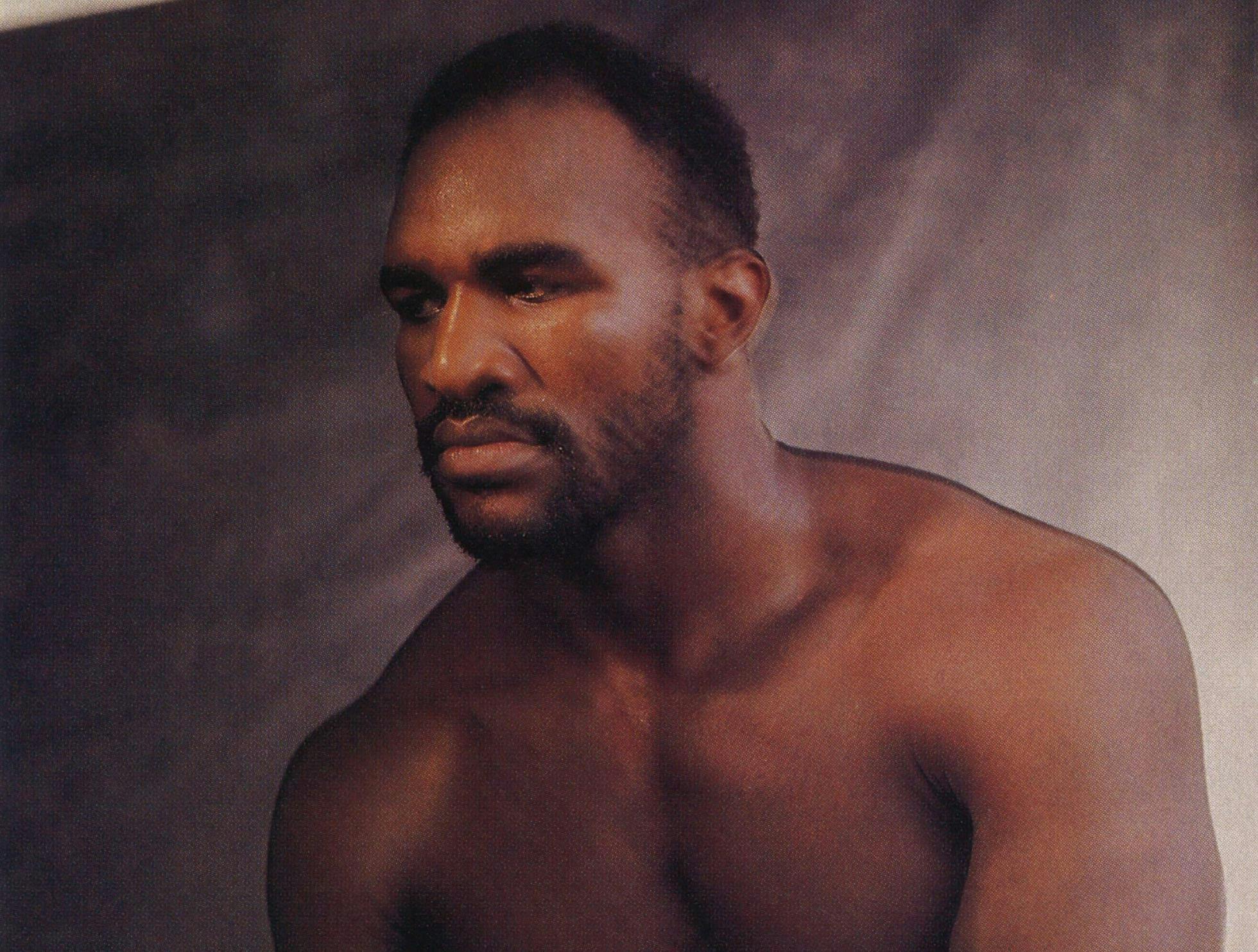

Holyfield didn’t look like a heavyweight; he looked like a Michelangelo sculpture. Every muscle group seemed to have been copied from Gray’s Anatomy, and all that was missing was the name tags. Outside the ring, he was unfailingly courteous and polite, and he seldom missed an opportunity to credit God for his success. People thought of him as nice, maybe too nice to beat George Foreman. “People don’t see me as a threat,” he admitted. “They see a guy who makes sense when he talks and doesn’t act crazy. I don’t intimidate people with my presence like Foreman or Tyson. For me, boxing has always been more mental than physical.” Only when he climbed into the ring did this sweet-tempered young man seem possessed. His ex-wife, Paulette, told an interviewer that she had been terrified the first time she had watched her husband fight, that she hyperventilated and broke out with hives. His relentless quest to become the heavyweight champion broke up their marriage—four children later—she claimed.

Paulette was primary among many problems that burned in Lou Duva’s ample gut. One of the champ’s greatest assets, Duva insisted, was his ability to handle stress, to focus on the priority of boxing and put personal problems aside. But toward the end of the second week of camp, on a day that Duva had promised reporters that his man would be sparring four rounds, Holyfield suddenly bolted, flying to Atlanta to take care of “personal problems.” Paulette had bumped her divorce-settlement demands from $4 million to $20 million, coincidentally the exact size of Holyfield’s purse for the championship fight. Holyfield was back after a few days, apparently as focused as ever. But you had to wonder. Sam Langford, a great lightweight in the early 1900’s, used to say, “You can sweat oat [out] beer, and you can sweat oat whiskey, but you can’t sweat oat women.”

To get his man ready for the fight, Duva imported a series of Foreman look-alikes as sparring partners. They arrived at camp like logs at a sawmill, each six foot four, 250 pounds plus, each a never-was posturing as a has-been, most strong enough to give the champ a taste of the mugging and mauling he could expect one month later in Atlantic City. With a ghetto blaster at ringside playing what sounded like rock music from hell, Holyfield went progressively longer each day.

“Don’t lose your cool,” trainer George Benton yelled above the music. “That’s what he wants you to do. Stay loose, stay loose … go with the flow.” Benton wanted Holyfield to push or pull away from the bear hugs of the imitation Foremans, to counter with uppercuts and punishing left hooks to the body. Since Holyfield was quicker and more mobile than Foreman, the strategy was to stay in what Lou Duva called “the zone,” far enough away to duck but close enough to counterpunch.

“Foreman is heavy-handed, what I call a club fighter,” Benton said. “He never knocks a guy dead with a sharp blow; he clubs him to the floor. Evander’s got to be flexible . . . stick and move, stab and move, in and out . . . make Foreman rush his punches, keep him busy, tire him out. Foreman was never known for his stamina, even when he was a young man.”

An amiable gentleman in his fifties, Benton was a sort of boulevardier with a fondness for wool golf caps, gold jewelry, and forgiving women. Like other members of the team, he wore a Real Deal T-shirt while working. Fie reminded me of Jersey Joe Walcott, the quick-study eyes, shoulders defined by many hours in the ring but none in the weight room. Benton grew up in North Philadelphia, in a tough neighborhood a few blocks from Johnny Madison’s Gym. Naturally, his mother forbade him to hang out with the rabble at the gym, and naturally, by the age of ten, he was working there as a towel boy. “When Madison sold the gym to Joe Rose,” Benton remembered, “he sold me with it. Rose started training me at age twelve and trained me until I retired at thirty-six.” A ranking middleweight in the sixties—he beat three champions but never in a title fight—Benton’s career ended in 1970 when a gunman, apparently mistaking him for someone else, put a bullet in his back. For the past fifteen years, Benton had trained for Duva.

One week before it was time to break camp and head to Atlantic City, Holyfield rounded into peak form by boxing twelve rounds with four different Foreman look-alikes. To contain the crowd, Duva stretched a rope between the front entrance and the ring, and positioned Al Evans to keep small boys from climbing underneath, an assignment that gave both Evans and the boys much pleasure. The only people allowed in the exercise area behind the ring were reporters, a few men in three-piece suits and Italian-made shoes, and members of Houston’s sports aristocracy, such as Dicky Maegle, the old Rice University all-American halfback.

Holyfield looked sharp. He had learned his lessons well. He stayed in the zone, dodging jabs and countering with fast, sure combinations to his opponent’s head and body—four, five, and six hard shots in a flurry. The imitation Foremans mauled, wrestled, and tied him up, but Holyfield kept his cool. Hallmark shouted encouragement—“real deal!”—and checked Holyfield’s pulse between each round. In the final two rounds, Holyfield’s lean, contoured body was lathered with sweat and he was breathing hard, but he was still sticking and moving.

Afterward, Duva personally removed Holyfield’s gloves and wraps, changed the boxer’s sweat-drenched T-shirt, and toweled him down as gently as a mother. “He got a little tired there at the end,” the manager acknowledged, “but remember, he was in there with four fresh guys. I don’t think Foreman is dumb enough to train for twelve rounds.”

JUST WHEN THE SWEET SCIENCE appears to lie like a painted ship upon a painted ocean, a new hero . . . comes along like a Moran tug to pull it out of the doldrums.

A. J. Liebling wrote that sentence in 1962 about a brash young heavyweight named Cassius Clay, but it worked just as well in 1991 when applied to George Foreman. This was one of the great stories in the annals of boxing—Foreman’s comeback. The appeal of the fight was international, universal, timeless. Try to remember the last time a heavyweight championship fight attracted this kind of interest. You had to go back to the days of Ali, Frazier, and Foreman. In 1973, when Foreman knocked out Frazier and won the heavyweight championship, people predicted that he would hold the crown for twenty years. Instead, he held it for slightly better than twenty months—until Ali, who had lost the title to Frazier, reclaimed it from Foreman in Zaire. Now Foreman had returned, two decades later, and the prophecy was on schedule.

People had laughed at the notion of a Foreman comeback, none more relentlessly than kingpin promoter Bob Arum, who predicted that no one would take the comeback seriously. Foreman fought in tank towns, against mediocre club boxers, for purses starting at a few thousand dollars. Averaging a fight every other month, Foreman fought himself back into shape. Gradually, the purses got larger, and so did the demands for his talents. After four years, he had won all 24 of his fights, 23 by knockouts. When Douglas beat Tyson, and Holyfield beat Douglas—and the doldrums sucked the wind out of boxing’s sails—Arum reviewed the situation. Working a deal with Duva’s Main Events organization, Arum made himself co-promoter of the championship fight. He first offered Foreman $10 million. Not enough, said Foreman, who negotiated for himself. Arum bumped the offer to $12.5 million. Nobody had ever paid a challenger that kind of money before, but then George Foreman wasn’t merely the challenger, he was the draw. “Foreman is the first fighter I’ve ever negotiated with directly who didn’t overestimate his worth,” Arum admitted.

In an era in which sporting events had become more complex than grand opera, Foreman was a one-man band. He was his own promoter, his own manager, his own trainer, even his own cut man—in a fight last July, George applied a butterfly patch to his own eye cut. “He’ll barely let you help him unlace his gloves,” said Mort Sharnik, Foreman’s publicist. Unlike Holyfield, who would split his purse many ways, Foreman would keep all except what he paid his attendants and advisers.

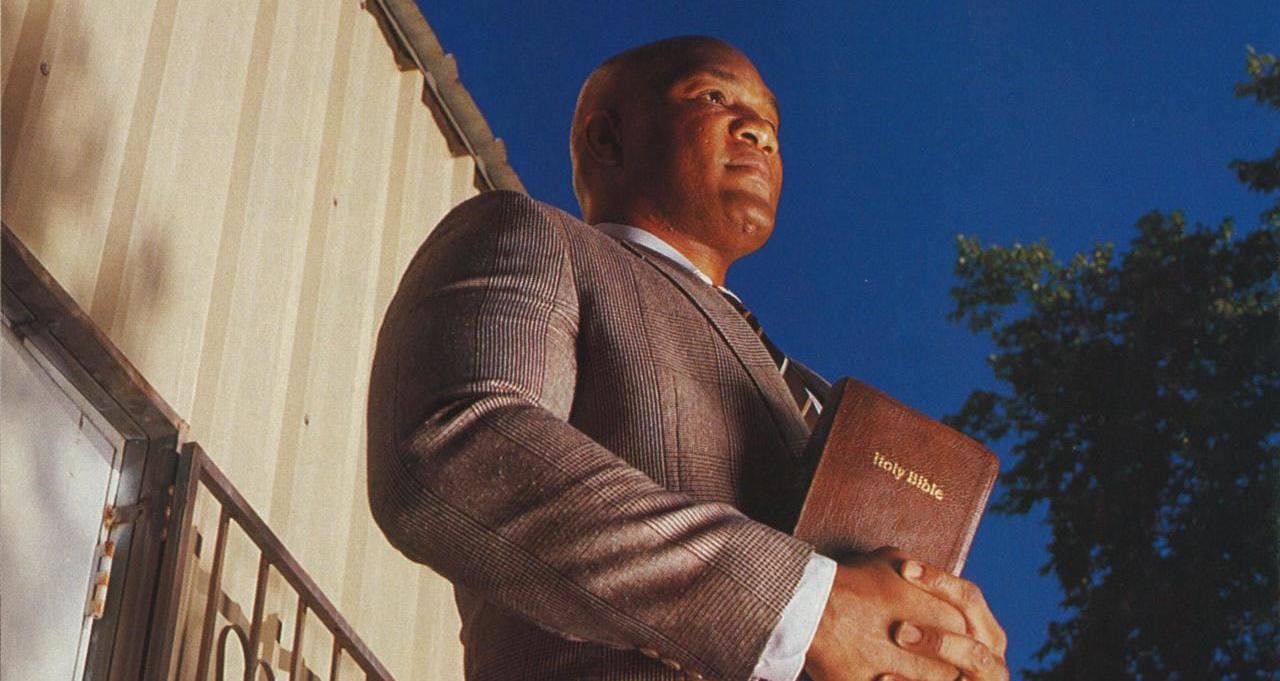

Nobody mentioned Foreman’s age anymore, except in awe. Reporters seemed fascinated by his weight—did he really return from the island of St. Lucia in January weighing just 240?—but that was no more than another rainy day angle for the press. The only people truly concerned about Foreman’s weight were those in Holyfield’s camp, who wished George would lose thirty or forty pounds. When George told reporters that dieting interfered with his sense of contentment—that he tended to hallucinate when he ate too lightly and that the franchise hamburger had changed his life—he wasn’t necessarily trying to be funny. Kathy Duva, Lou’s daughter-in-law, who was in charge of publicity for Main Events, told a member of Foreman’s camp, “We’re really glad that George is taking this fight seriously,” illustrating how badly Holyfield’s people misread the situation. Foreman had been as serious as rent right from the start. His motive for a comeback may have been charity—he wanted to build an indoor arena for his youth club in Houston, and he had done that and a lot more with his winnings—but beyond the altruism was his deep-seated conviction that God wanted him to be the heavyweight champion of the world again. “It is my destiny,” he said. “It is in the stars.”

Not since Muhammad Ali had there been a heavyweight with such charisma and mystique. In the soft light of his reincarnation, Foreman emerged as a philosopher, wit, and elder statesman, roles he very much enjoyed. In his spare time, this ninth-grade dropout read War and Peace and books on the Depression, the Holocaust, and the New Deal. George wrote his own dialogue, coining a repertoire of self-effacing quips and one-liners that made him the hit of talk shows. “People say I made my comeback fighting guys just off the respirator,” he would growl, looking menacingly at the camera. “That’s a lie! I didn’t fight nobody hadn’t been off the respirator at least eight days.” Publicist Sharnik, borrowing a gesture from The Great White Hope, got Foreman to shake his fist like Jack Johnson and call out defiantly, “Here I is!” Interview requests poured in from all over the world. “This fight transcends boxing, even sports,” said Sharnik. That wasn’t just hyperbole from an overwrought PR man. As an investigative reporter for Sports Illustrated and later the boxing coordinator for CBS television, Sharnik had been around sports for thirty years.

Foreman had a compulsion to control his own environment and an aversion to sharing the spotlight. Sharnik wanted to invite Willie Nelson, Nolan Ryan, Ann Richards, and Bill Moyers to a “Texas Treasures” barbecue in Houston—the idea being to establish that Foreman belonged in such company—but George vetoed the idea. Nor in the weeks before the fight would he agree to appear on the same talk show as Holyfield. “Why should I?” he asked. “My task is to put him in the shadows.” But as the moment drew closer when he would share the ring with Holyfield, Foreman became more pensive and introspective. At times like this, he always retreated to the sanctuary of his heavily wooded two-hundred-acre ranch near Marshall.

The small East Texas town of Marshall had a mythical pull on Foreman. This was his place of birth. Though his mother took her flock of children to Houston’s Fifth Ward when George was a baby, he had returned as heavyweight champion of the world and tracked down his true father. One of the many things Foreman and Holyfield had in common was that they grew up dirt poor, the babies of large families raised by deeply religious, hardworking mothers, and years later, fame and fortune secure, both returned to their roots to face their biological fathers. Later, George preached at the old man’s funeral, then he placed his Olympic medal and his championship belt in the Harrison County Historical Museum in Marshall and bought a ranch south of town. The ranch was a sort of memorial. It was also the place he went when he wanted to be left alone.

In the final weeks of training, reporters who found their way to Marshall had no guarantee that they would actually see George Foreman. Except when his wife and children were there, George lived alone in his four-bedroom brick ranch home, seldom venturing outside the chain link fence that surrounded the property. The compound included a house for his mother, a bunkhouse, stables for his Tennessee walking horses, two stocked fishing ponds, and a new tan-colored corrugated-iron gym—a replica of his church in northeast Houston. The gym was spartan. It had no dressing facilities, no mirrors, and bare panel walls, the monotony broken only by a large American flag displayed across one side of the interior. Equipment was minimal: some weight machines and a heavy bag. George held the speed bag in contempt, but the heavy bag was a virtual addiction. Sometimes he pounded it for the equivalent of fifteen or eighteen rounds, and what you noticed on collision was that the bag moved but his body didn’t, not a ripple.

The only person who saw Foreman regularly was an apprentice boxer and weight lifter named Bobby Cook, who worked out with him daily. Cook was Foreman’s majordomo, on 24-hour call: When he went into town, he wore a beeper and carried a cellular telephone. Cook had curly brown hair and looked something like Mel Gibson—Foreman called him “my golden boy.” He appeared to be in his early thirties, though Foreman had advised Cook to not reveal his true age. Since he had had only seven professional fights in four years, Cook didn’t have a clue about how to train for a championship fight, which was precisely the reason Foreman liked having him around.

Foreman made up his training schedule as he went along. He got out of bed when he wanted to, somewhere between four in the morning and noon. Unless his wife or mother was in camp, George did the cooking for both himself and Bobby Cook. Spiced turkey legs was his specialty. After breakfast, depending on how he felt that day, he would chop down hardwood trees for two or three hours, work on the heavy bag, and maybe spar five or six rounds. Or maybe he would take a nap. Sometimes he would harness himself to a wagonload of firewood and jog across a pasture, his yearling colt trotting behind. Some days he wouldn’t work at all.

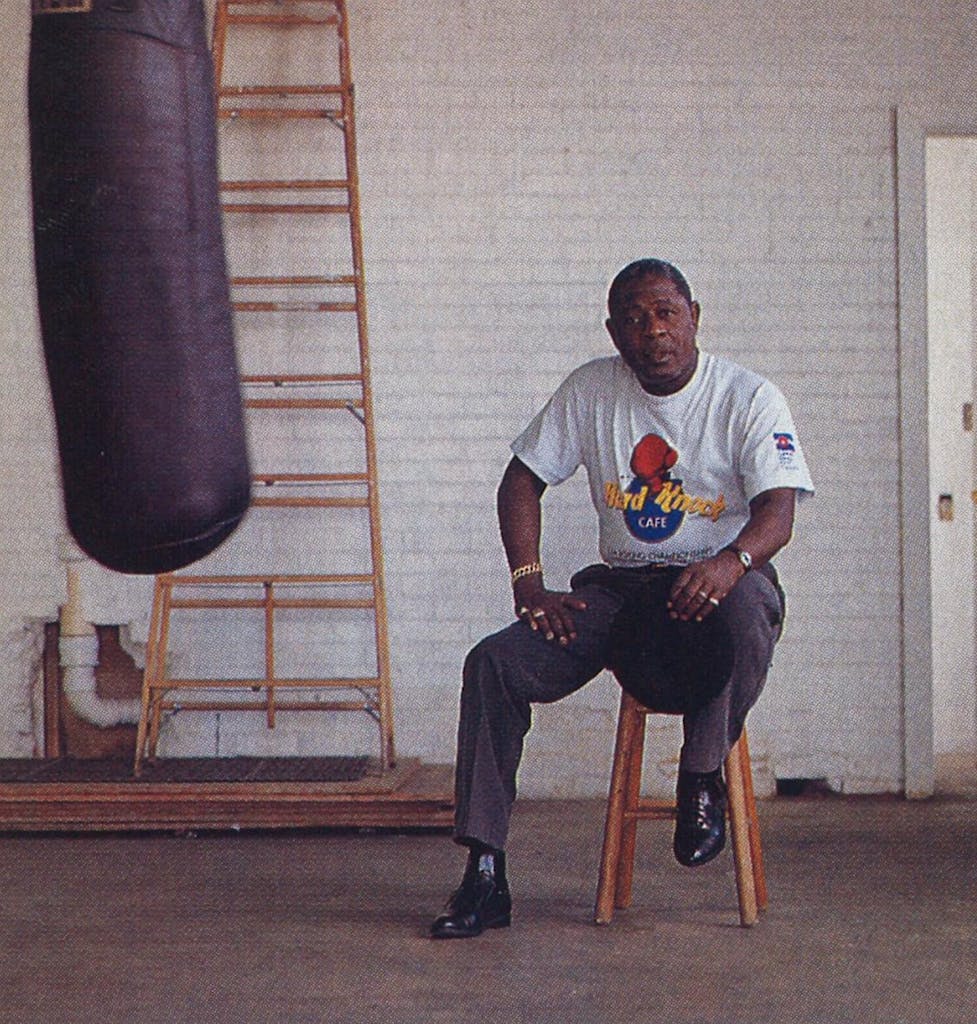

Five sparring partners and a small number of “advisers” stayed in town, at two motels on either side of the intersection of Interstate 20 and Texas Highway 59. The only adviser Foreman even pretended to consult was the great light-heavyweight champion of the fifties, Archie Moore, a ring legend whose 234-fight career spanned nearly thirty years—1935 to 1962—and included the incredible feat of holding a world’s title at age 49. They used to call Moore the Mongoose, a tribute to his ability to dodge incoming blows. “I could take a punch, but it is prudent to evade them,” explained the Mongoose, who talked like a character in a Bullwinkle cartoon. “Constant punching can cause severe implications over time.” Foreman claimed that Archie taught him “breathology, escapeology, and all them other ologies.” Contradicting Archie Moore would have been as unthinkable as sassing his own mother, and yet Foreman was able to pay homage to the 77-year-old immortal without asking a lot of questions. Moore spent most of his time in town, hanging out at a pawnshop or imparting his wisdom to visiting journalists. What George Foreman really listened to was his own body.

Most of Foreman’s attendants were straw men, retained because of old loyalties or family ties. Ron Weathers, a burly, bearded former gambler and saloon keeper from El Paso, was there because he had promoted most of Foreman’s comeback fights, which meant that he booked arenas and made up the difference out of his own pocket when gate receipts failed to cover expenses. “Promoting is a sickness, just like gambling,” Weathers told me. “After you’ve booked enough losers, you’re praying for just one winner—just one—and then you’ll quit.” In payment for his good faith, Weathers had been given a small piece of the promotional rights of the championship fight.

Even in isolation, Foreman found time to watch or read everything the media said about him. That distressed Sharnik, who couldn’t predict how George might react. Three weeks before the fight, for example, a report on the CBS Evening News called Foreman “old” and “bloated” and referred to him as “a cafeteria with arms.” George got a chuckle out of that. But at almost the same time, an article in the Houston Chronicle said that Foreman had turned surly and was reverting to the Sonny Liston-like scowls and recalcitrant nature of his younger years. What particularly galled George was that the story quoted Lou Duva at length. Duva said that he couldn’t imagine what was going on at Foreman’s camp and speculated that “maybe they don’t have control . . . over there.”

In the war of nerves that foreshadowed every championship match, Duva was a master. He was using the media to needle Foreman, and he was getting away with it. George sulked for several days. Then he invited media representatives to the ranch, where he proceeded to tie one end of a bull rope to his two-ton pickup and fashion the other end into a makeshift harness, which he slipped over his shoulders. The rope burning into his flesh, Foreman towed the truck a quarter of a mile along a gravel road.

Later Sharnik said, “George is a little apprehensive now, but as soon as we get to Atlantic City, he’ll be okay. He calls it ‘cutting in.’ He’ll cut in—reach a sort of state of grace—and after that nothing will bother him.”

THE REASON THIS FIGHT WAS HELD in Atlantic City was Donald Trump, who had guaranteed the promoters an $11 million site fee to use Trump Plaza, then tried to weasel out. The only two cities in America that were still interested in hosting a heavyweight championship fight were Las Vegas and Atlantic City, a situation that didn’t flatter the sweet science but one that was increasingly irrelevant. The enchilada grande for this event—and for all future events of this magnitude—was pay-per-view and closed-circuit television, which together eventually attracted an audience of 1.5 million homes and grossed $77 million. The rest was thin gravy: They could have held the fight in Donald Trump’s hat, and nobody would have known the difference.

Atlantic City seemed as good a place as any to stage what was essentially a primordial event in which members of the lower class attempted to beat each other to death for the profit and amusement of the upper class. In the decade since Trump and men like him had arrived to build their casinos, the old seaside resort had been ground into dust. Beyond the neon hum and ostentatious glitter of casino row, along dark, rutted, debris-strewn streets that belonged in Beirut, Atlantic City was boarded up, bombed out, leveled. The Victorian homes, the rambling hotels with turrets, parapets, and profusions of balconies, the mom-and-pop groceries that offered credit, the neighborhood bars, theaters, parks, trees, birds, people . . . gone, all gone. The famous Boardwalk was now a back path for the casinos, a way to get from one dice table to another and still claim to have seen the ocean. As in times past, the Boardwalk’s landward side was lined with hole-in-the-wall shops selling cheap jewelry, novelties, saltwater taffy, hot dogs, pizza, and fresh lemonade. Its intersections were identified still by Monopoly-board names like Park Place, St. James Place, and Connecticut Avenue, but people no longer came to fish or swim or luxuriate in the simpler pleasures of life. In most cases they didn’t even spend the night. They came by bus, day-trippers from New York or Philadelphia, wild-eyed to get to the slot machines. Atlantic City made Las Vegas look classy.

Both fighters and their entourages stayed at Trump Plaza, and so did almost everyone else connected with the fight. There was hardly a nook of the hotel that didn’t offer a reminder that the Battle of the Ages was upon us. Posters of Foreman and Holyfield lined the plush corridors, alongside posters of such coming attractions as Eddie Fisher and Theodore Bikel. One of the hotel’s ten eating places featured the George Foreman Buffet. Gift shops sold posters, programs, caps, and shirts printed with photographs of Foreman and/or Holyfield. TV sets that were suspended from ceilings just outside the casino entrances played commercials continuously. There was Big George in a rocking chair, saying, “I’m just a baby boomer, but I’m gonna lower the boom on that baby Evander.” When you telephoned the hotel and got put on hold, you heard the voice of Evander saying that George must be off his rocker. That was about as nasty as it got. This was a fight in which nobody even pretended to be mad at anyone else.

A ring was constructed in the Imperial Ballroom, just down the hall from the pressroom, and the fighters trained there daily—Holyfield in the morning and Foreman in the afternoon. All of Holyfield’s sessions were open to the public, for an admission price of $3, but when Foreman trained in earnest, he admitted no one, not even the media. Big George wasn’t trying to hide, just concentrate.

Other than the times when he was actually working, Foreman was almost unavoidable. Six days before the fight, he preached a sermon at Atlantic City’s Shiloh Baptist Church. You saw him in the hallway or the lobby of the hotel, an unmistakable figure in a floppy red hat and red-tinted sunglasses, always surrounded by admirers. When he took his daily strolls with Archie Moore along the Boardwalk, crowds flocked like sea gulls, and George stopped to answer questions and bump fists—his way of shaking hands. He would pop into the pressroom unannounced and stay for two or three hours, until the questions became redundant and even ridiculous. Q. Have you ever had a cut problem? A. Not since the Fifth Ward.

Even the cynics—and there were many among the press corps—got caught up in George’s shtick and found themselves swapping favorite quotes. What was it George said about Holyfield’s strength coach? He said he had a strength coach, too—his wife. He said she put big chains around the refrigerator at night, and they were so strong that he couldn’t break them. On the night of the weigh-in (Foreman pushed the scale to 257, nearly 50 pounds heavier than Holyfield), George was back in the pressroom, eating fruit salad and calculating how many cheeseburgers he would need to consume to get his weight up to the record 270, which was how much Primo Camera weighed when he went fifteen rounds against Tommy Loughran in a title fight in 1934.

Holyfield, on the other hand, was seldom seen except when there was a press conference or a scheduled workout. It was the champion’s nature to be retiring and understated. On rare occasions, Holyfield and his entourage would pass through the lobby, wearing the snappy blue-and-orange team jackets that Duva had selected for the fight, but people were not always sure which one was the champion. One might assume that Holyfield resented being merely a prop for Foreman’s one-man show, but in fact, he seemed to enjoy it. “George is funny,” Evander said. “That’s his thing, and it’s good for business.”

“Holyfield’s idea of a good time is wearing brown shoes with a tux,” said Bert Sugar, the editor of Boxing Illustrated. Sugar had become the fight game’s unofficial historian since the death of Nat Fleischer, and he probably gave more interviews than both fighters put together. A lanky Runyon-esque character in a floppy gray fedora, blue blazer, garish scarf, and silk trousers with a print of little fish, Sugar gestured with his trademark cigar when he wanted to make a point. Many cynics had this fight figured as a sham—a front-page story in the Philadelphia Inquirer on the day of the fight called it “one of the most charming con games ever played”—but Bert Sugar disagreed. “To say that Foreman has only a puncher’s chance is the most classic understatement since a Crow scout told General Custer that there might be a little trouble along the banks of the Little Bighorn,” Sugar told me.

In the five days leading up to the fight, more and more people were picking Foreman. There was no sports book in Atlantic City, but reports from Las Vegas said that most of the betting was on Foreman, who was getting three-to-one odds. Archie Moore, always the mystic, hinted that George had developed a technique to offset Holyfield’s speed, though he wasn’t at liberty to discuss it. “I can’t divulge secrets that must not be known to wayfarers,” said the Mongoose, who could usually be found sitting (and sometimes napping) on a chair just inside the pressroom door, a white knit hat warming his ancient gray head.

With Moore in his corner—and with the addition of Angelo Dundee, who arrived a week before the fight—Foreman had better than a century of ring experience at his call. Dundee was one of the storied figures of boxing. He had been in Muhammad Ali’s corner the night that Ali bamboozled Foreman in Zaire, far and away the most humiliating experience in Foreman’s career. George had always believed that someone drugged his drinking water that night, though he didn’t blame Dundee. Angelo’s presence here in Atlantic City was mostly symbolic and motivational, but he could be viewed as a counterweight to Lou Duva, whose fiery Italian temper had been known to intimidate referees and ring officials. “He’s our capo,” said Ron Weathers. At the rules meeting two nights before the fight, Dundee demonstrated the point, arguing successfully, over Duva’s vitriolic objections, that the water for both corners must be supplied by the boxing commission.

On the day of the fight, Foreman had his usual fare: bacon and eggs for breakfast, roast chicken for lunch, prime rib for dinner. It is not recorded whether he had a late-evening snack—the fight didn’t start until eleven-fifteen—but it would have been in keeping with his belief that food nourishes the soul as well as the body. Many old-time managers concurred. John L. Sullivan ate beefsteak or mutton chops three times a day when he was training. One of Jack London’s most poignant stories told of a boxer who could not muster the strength for one final rally because his family butcher had refused credit for a bit of beef before the fight.

The crowd at a heavyweight championship fight may not be richer or more important than the crowd at any other major sporting event, but it acts like it. Trump and his blond bimbo, Marla Maples, preened at ringside and strutted along the corridor leading to the dressing rooms, at all times flanked by a squad of goons in dark suits. Jesse Jackson pumped hands and waved. Pat Robertson made himself apparent—Pat Robertson!— is this a great country or what? The list of celebrities introduced by the ring announcer sounded like Academy awards night: Kevin Costner, Gene Hackman, Robert Duvall, Sylvester Stallone, Billy Crystal. The biggest hand of all was for Muhammad Ali, who gimped down the aisle with his coterie and joined Joe Frazier in the ring.

The casinos had bought blocks of $1,000 tickets for favored customers, and there were obviously many high rollers seated in the first fifteen or twenty rows. Though ticket prices were scaled from $100 to $1,000, all the seats on the floor of the mammoth convention hall (capacity: 19,000) appeared to be the $1,000 variety, at least for tax purposes. The ratio of men to women, I’d guess, was five to one, but the women were, almost without exception, gorgeous, stunningly dressed, and attached to the arm of some guy who looked as if he swapped toxic-waste contracts for a living. It was the ultimate statement of woman-as-ornament.

The crowd was overwhelmingly pro-Foreman. There was thunderous applause as the challenger approached the ring, led by his handlers in their red- white-and-blue jackets with “USA” sewn on the sleeves. One of George’s men carried an American flag. George’s wide face was absolutely radiant under the hood of his red terry cloth robe: This was the moment he had waited for, worked for, prayed for, dreamed of. More subdued was the reaction to Holyfield’s entrance, but the champion appeared quietly confident. He knew what he had to do.

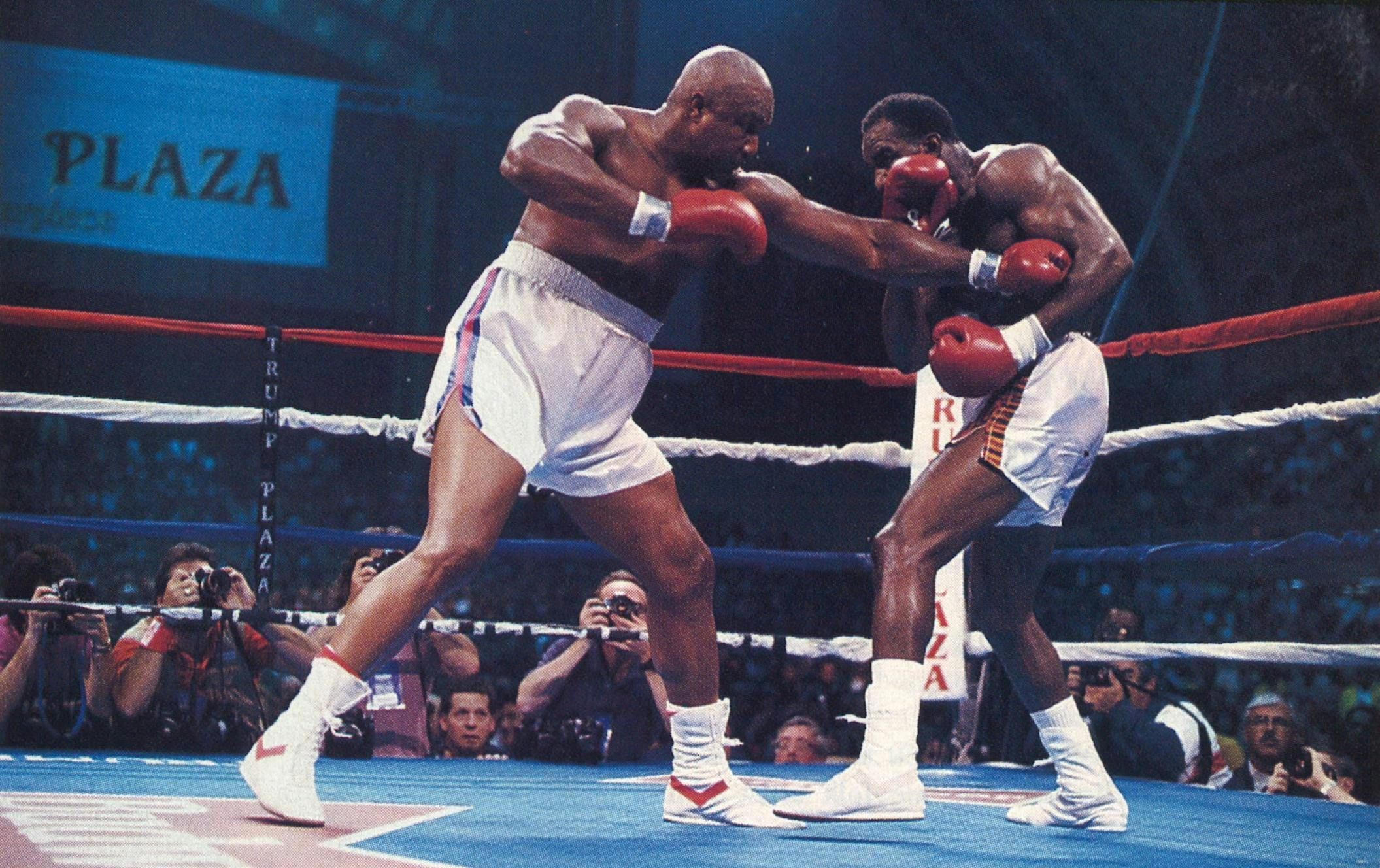

Looking back, it was Holyfield’s fight all the way. Foreman had his moments, especially early, but Holyfield was always able to rally. Foreman stung Holyfield with a clubbing right near the end of the second round, bringing the crowd to its feet, but Holyfield answered in the third round, rocking Foreman with a left hook to the head and scoring freely at the bell.

Holyfield was fighting smart, holding to the plan that trainer George Benton had laid out, sticking, stabbing, moving, staying close, forcing Foreman to swing wildly or, more often, cover his face and upper body with his massive arms and wait for the assault to subside. “When Foreman’s hiding,” Benton had said, “he ain’t hitting.” But Foreman kept coming, taking more than he was giving, yet always a threat to end it with one punch.

Foreman’s last good opportunity came early in the seventh, when an overhand right sent Holyfield reeling backward. Holyfield tried to clinch, but Foreman pushed him away and continued the barrage. The champion somehow collected himself, retaliating with hooks to the head and jabs to the body. You had to admire Holyfield’s moxie, the way he ignored the crowd, which was chanting George’s name now, the way he maintained his concentration, putting together combinations in batches of six or seven. Late in the ninth round, Holyfield had Foreman against the ropes, but the bell saved the challenger, and George wobbled back to his corner, dazed but still defiant, shaking off Angelo Dundee’s offer of a stool. Foreman never once sat down between rounds, even when he could barely stand.

Knowing that he was ahead on points, Holyfield fought defensively in the final three rounds. Even so, Foreman was never more than an uppercut from regaining the title. By the twelfth and final round, both fighters were hurt and exhausted, and still they continued to attack until the last seven seconds of the fight, when Holyfield sort of pulled Foreman to his body and hugged him. “I love you, man,” Foreman whispered in the champion’s ear. Holyfield nodded. It no longer mattered what the cynics said. This had been a classic battle between two great warriors, one of them a little younger and a little quicker and little more able than the other. This had been a display of courage and dignity and ringsmanship rarely surpassed.

Fans lingered near ringside, thousands of them, standing on chairs or clogging the aisles, knowing that there was nothing more to see and yet feeling an urgency to pay their respects. Some had booed Holyfield, especially in the late rounds, and this was a time for atonement and absolution. Some had given their hearts to Foreman, and this was a time to say that they would do it all over again. After awhile, they filtered out of the convention hall and onto the Boardwalk, ignoring the early morning chill, talking, reviewing, critiquing, basking in the afterglow. Kids ran among the crowd, wads of unauthorized Battle of the Ages T-shirts bulging beneath their coats, hawking the shirts for $10 each until the cops chased them away. The throngs crowded the casinos and packed the few eating and drinking places that were open after midnight. Somehow they needed to sustain the magic, even if it was only in the company of one another.

In the dressing room later, Holyfield said that he had hit Foreman with everything he brought and it still hadn’t been enough. “He just kept coming,” Holyfield said, shaking his head in admiration. George offered no excuses, no alibis. Though his face was swollen and his lip split, he still was able to joke. “I was winning,” he said, “until Lou Duva snuck that mule in the ring.” Foreman said he was going to fly home to Houston and preach Sunday morning at his own church. Maybe he would box again—obviously the money would be there—but his admirers hoped that he wouldn’t. There was nothing more to prove. Let the quest end here. George Foreman had lost on the scorecards, unanimously. And yet, as George himself might have said, it had been a victory for . . . pork chops, cornbread, black-eyed peas, pumpkin pie, grannies and grandpas, the overweight, the underappreciated, the unobserved, old dogs and kitty cats, the world.

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- Gary Cartwright

- Donald Trump