This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The rain began late Wednesday afternoon, a slow soaking that lasted through the night. When he awoke on Thursday morning and saw that the rain was still falling, Andres Sarabia knew that it would be a bad day for San Antonio’s heavily Mexican American West Side. Soon families on Inez Avenue, a few blocks south of Saint Mary’s University, would be packing up their belongings and seeking refuge on higher ground; every time there was a big rain, the giant Mayberry drainage ditch behind their houses would turn into an immense thrashing lake. Muddy water lines on the houses ominously marked the extent of the most recent floods: two feet, sometimes three feet, high on the white frame exteriors.

Closer to town, Elmendorf Lake couldn’t hold the water that was streaming into it, and neither could Apache Creek, which wound east and south from the lake toward the stockyards and packing houses southwest of downtown. Apache Creek was a killer; few rainstorms hit the city that the creek didn’t claim a life or two, usually kids trapped on the side away from home by the sudden overflow.

Sarabia shook his head and allowed himself a short, bitter smile. People said this was an act of God; well, he knew better. There was just too much water with no place to go. Aside from a major thoroughfare or two, no street on the West Side had any drainage. You could drive for miles on curbless streets without seeing a storm drain. Even the huge ditches, some as wide as a river, that were supposed to carry off the water were choked by high grass, trees, and everything from grocery carts to old washing machines. None had even been cleared, much less channelized. Instead the water just seeped into the ground until the ground couldn’t hold any more, then it flowed down the streets toward the drainage ditches until they couldn’t hold any more, then it just stayed where it was, sometimes for days. Sarabia got into his car and began to pick his way through the flooded streets toward Kelly Air Force Base, where, like thousands of West Siders, he was employed as a civil service worker. Something had to be done. But what?

South of the stockyards Beatrice Gallego watched the river flow in front of her home and asked herself the same question. Actually that wasn’t a river; it was Winnipeg Street, but heavy rains turned it into a muddy torrent. She thought about her oldest child, Terry, whose trophies for beauty contests and softball tournaments were all over the house, walking to school barefoot, ankle-deep in mud. Perhaps she should ask one of her women’s clubs to send another petition to the city; maybe the city would do something this time.

The city would do something, all right, though not this time. On that rainy September day four years ago, Sarabia and Gallego couldn’t have foreseen—they didn’t even know each other—that they would help change the face of the city, not only physically but also politically; that they would become the leaders of the most unlikely political organization any Texas city has ever seen; or that they and their followers, most of whom earn less than $10,000 a year, would decide how the nation’s tenth-largest city spends hundreds of millions of dollars.

Today their organization, known as COPS (Communities Organized for Public Service), is firmly established in San Antonio as a major political force—some would say the major political force. It has won victory after victory, everything from large drainage projects and neighborhood parks to single-member city council districts, and yet its importance transcends any or all of these. For COPS has proved that you can fight city hall; it has challenged the basic assumption that pervades municipal government in every major American city: that ordinary citizens should leave things to experts, interest groups, and politicians. And, perhaps most important, it has unleashed San Antonio’s majority (and politically long dormant) Mexican American population, a fact that has in turn panicked the Anglo North Side, where people speak openly of a city divided into two camps and a Second Battle of the Alamo for political control of the city.

For most of the last quarter century, the quest for power in San Antonio was a triangular struggle among the staid Anglo business and social establishment, an increasingly large and vocal group of fast-money Anglo land developers and other outsiders who wanted action and lots of it, and an ambitious Mexican political clique trying to shoulder its way into the game. (Local folks of both ethnic groups use Mexican as shorthand for Mexican American, just as Bostonians talk about the Irish, rather than Irish Americans.) Most of the time the old-money gentry held the upper hand, and the standard interpretation of San Antonio politics has been that this ruling class sought and exercised power out of a sense of noblesse oblige, while the fast-money boys sought power mainly to further their own interests. It didn’t really matter why the Mexicans sought power because they never got any.

All that has changed now. The political arm of the ruling establishment, the Good Government League (GGL) is in ruins; the developers’ hegemony, after four stormy years, has been shattered, and the Mexicans can no longer be ignored. It is anybody’s ball game—literally anybody’s; the rise of Andy Sarabia and Beatrice Gallego is proof enough of that. What a strange place for all of this to be happening: stuffy old San Antonio, the only city in the U.S. outside of New Orleans where social status is determined by men; a city where what club you belong to really matters, not just socially but politically and economically; a city that somehow missed out on the economic miracles that transformed Houston and Dallas—something its self-conscious citizens have never accepted and can’t understand. And here it is, the first city in Texas to experience the ethnic political upheavals that will someday surely come to Houston, Dallas, and the rest: from noblesse oblige to the Second Battle of the Alamo in five years.

White Man’s Burden

Asked if San Antonio is in fact headed for a Second Battle of the Alamo, a local Mexican activist snapped, “Yes—and this time we’re going to win.” They won the first time, of course, but no one, Anglo or Mexican, thinks of it that way. The Alamo is where it all started, this century and a half of ethnic tension that has gripped and shaped and at times even blessed San Antonio, giving it a unique character and depth no other Texas city can approach. Seldom has that tension been pushed far into the background: not in the years immediately following Texas independence (Mexican national troops intermittently occupied the town between 1836 and 1848); not by the time the railroad arrived in the 1870s (Germans began to control the town’s banking and commerce and had replaced Mexicans as the town’s dominant ethnic group); and certainly not in the first half of the twentieth century, when San Antonio neighborhoods were segregated by deed restrictions, San Antonio schools were segregated by tradition, and even downtown was tacitly segregated by Flores Street.

But seldom has the city been as divided as it is today. With the 1970 Census, Mexicans are again a majority of the population—a fact that by itself would be enough to make Anglos uneasy. Enrollment in the San Antonio Independent School District is 70 per cent Mexican and only 14 per cent Anglo; the school board is in Mexican hands and the eleven-member city council is headed that way. It has five Mexicans and one black, giving ethnic minorities a majority, and crucial votes often split right down the ethnic line—a development that delights some of the Mexican councilmen and dismays others. For the first time the central fact of San Antonio’s existence—its ethnic diversity—is reflected in its politics, and though there is an almost universal sense that this is healthy, no one seems to know where to go from here. Like Europe before 1914, San Antonio appears headed for a war nobody wants and nobody thinks can be avoided. There is no ground swell for bridge builders, though one of the Mexican councilmen, University of Texas at San Antonio professor Henry Cisneros, is ideally suited for the role. For a time he seemed destined to be the city’s first Mexican American mayor in over a century, but events may have overtaken him.

Even Anglos of goodwill—and there are many in San Antonio—are starting to be afflicted by the same kind of doubts that plagued sympathetic white Southerners during the civil rights movement. What is wrong with these aliens in our midst? Why can’t they become “Americans?” Why can’t Mexicans do what the Germans and the Irish and the Italians and the Jews did when they came to this country?

There is no one answer to such questions. Some say the discrimination has been greater; some point to the psychological burden of being a conquered people (going back long before the Alamo, all the way to Cortés); others talk of vast cultural differences, theorizing that the Protestant ethic so basic to the Texas character is missing from the Mexican’s heritage. But at least part of the reason rests on something so basic as geography. When the Germans, the Italians, the Jews, came to America, they came in great waves—and they stopped. There was an ocean between them and the Old Country. They had to assimilate; there was nothing else to do.

The difference between the European and the Mexican is the difference between an ocean and a river. There was no single wave of Mexican immigration; rather it was a steady trickle that began in the early years of the twentieth century, when South Texas was cleared for agriculture and revolution broke out in Mexico. There were always more Mexicans arriving, more family to be cared for, and though the front end of the community disappeared into the melting pot, the back end never seemed to diminish. The constant tension between front and back tugged on the middle and never allowed it to break loose from its past.

Meanwhile most Mexicans had little to do with the political or economic life of San Antonio, mainly because they were too busy trying to survive; tens of thousands got through the Great Depression by shelling pecans for a few pennies a pound. Who had the money to throw away for a poll tax?

A few Mexicans, though, were very much involved in politics. From the twenties through the forties San Antonio was run by a strong and corrupt political machine that stayed in power by handing out municipal contracts and city jobs. During the height of the Depression opponents charged that there were 3000 mattress inspectors on the city payroll; the machine hired city employees for their political connections and expected them to deliver their friends and relatives on election day. To this core the machine added the small ethnic vote on the Mexican West Side and the black East Side. No racial ideology was involved; the machine simply bought the loyalties of a few key organizers with favors, and these henchmen in turn bought poll taxes for their minions. Usually the favors involved protection for vice: West Side political meetings took place above the brothels on El Paso Street, and every prostitute had a poll tax.

“They jammed into the council chambers in such numbers that one councilman was reminded of Travis’ famous message from the Alamo: ‘I am besieged with a thousand or more of the Mexicans.’ ”

The machine gave way to the Good Government League in the fifties, and politics began to open up a little for the West Side. A Spanish-language newspaper editor’s son named Henry B. Gonzalez ran for city council and won; he survived a turbulent term when the city went through 48 councilmen in two years to win again. For the West Side Gonzalez was the right man at the right time. As basic as drainage was to be in the seventies, the issue in the fifties was more basic still: it was philosophical and political acceptance of the Mexican American as a part of San Antonio. Gonzalez symbolized that acceptance, but just as important, he was worthy of it. He took no money, he cut no deals, he spoke out for what was right, and his people revered him for it. He shattered his constituents’ own stereotypes about corrupt Mexican politicians and eradicated the memory of the whores with their poll taxes. That is why even today there are hundreds of people on the West Side like the old man who runs a gas station on Zarzamora Street, proudly showing visitors a frayed, yellowed letter Henry B. wrote him twenty years ago.

The GGL began as a reform movement, bent on bringing professional city government to San Antonio (“a copy of the American corporate structure applied to politics,” Walter McAllister called it; he would become mayor in 1961, at the age of 72, and serve into his eighties). For a century, ever since the early Germans had been too busy making money to pay much attention to politics, San Antonio’s leading citizens had shunned city hall, but now they invaded it to run the town as it had never been run before: everything from paving long-neglected streets to bringing the city a world’s fair and a branch of the University of Texas.

And yet, underneath the smoothly running exterior, all was not well. From the start the GGL made no effort to cultivate new Mexican political talent and develop a critical mass of West Side support. Instead, like the old machine, it chose to deal with the West Side through a few handpicked intermediaries—although in keeping with the changing times, its contacts were Mexican American businessmen, not vice peddlers. As a result there was no political outlet for ambitious young Mexicans: no spots on the city council, not even appointments to city boards and commissions. As for other electoral races, that didn’t sit well with Gonzalez, who by the time McAllister became mayor in 1961 had gone off to Congress—but not before spreading the word around the West Side that “there is only one politician here and that is me.” The only refuge left for Mexican political hopefuls was whatever liberal Democratic organization happened to be functioning at the time: Viva Kennedy, PASO, Mexican American Democrats. The names changed but the clique didn’t. They sat around, drinking and complaining and talking of the days when they would have power and cutting each other up, as liberals will. Some went on to become lackluster state legislators; others, even now, are waiting their turn, laying plans to reap the spoils of the Second Battle of the Alamo.

Ambitious Mexicans weren’t the only ones who felt excluded by the GGL. San Antonio’s council-manager system had gone to great lengths to keep politicians from making money out of government. (Two crucial city departments, water and electric utilities, were governed by self-perpetuating boards completely free of council control.) But no system could erase the fact that money was there to be made. Fortunes depended on where the city built water mains, how it enforced subdivision regulations, and what it decided about zoning. Builders and land developers yearned for city policies that stimulated growth, but the GGL was composed primarily of Chamber of Commerce types—downtown businessmen and merchants, many from old families, who had little incentive to tilt city policies in favor of suburban growth. These natural economic tensions were heightened by the social conflicts between the GGL’s old families and developers with nothing but contempt for bloodlines.

After McAllister finally stepped down in 1971, no one could hold the GGL together. The telling blow was delivered by a maverick GGL councilman named Charles Becker, son of the founder of the Handy-Andy grocery chain and a member of an old San Antonio family. Despite his GGL ties, Becker had far more affinity with the fast-money boys than with the stodgy old downtown crowd who, said Becker, spent their time “lollygagging” around the San Antonio Country Club and the Argyle Club, pruning their family trees. When the GGL needed the West Side votes, they weren’t there, and suddenly the GGL was O-U-T. Familiar names on city boards and commissions were replaced by Becker allies; before long, the president of the Greater San Antonio Builders was in charge of the planning commission and a major developer was chairman of the powerful water board.

Becker loved to talk about his feud with the GGL; his favorite saying was, “I’m gonna kill me some snakes.” But, it turned out, that was all he did; he destroyed the old order but built nothing new to take its place. When he quit in 1975, his legacy was a power vacuum.

Old Story, New Ending

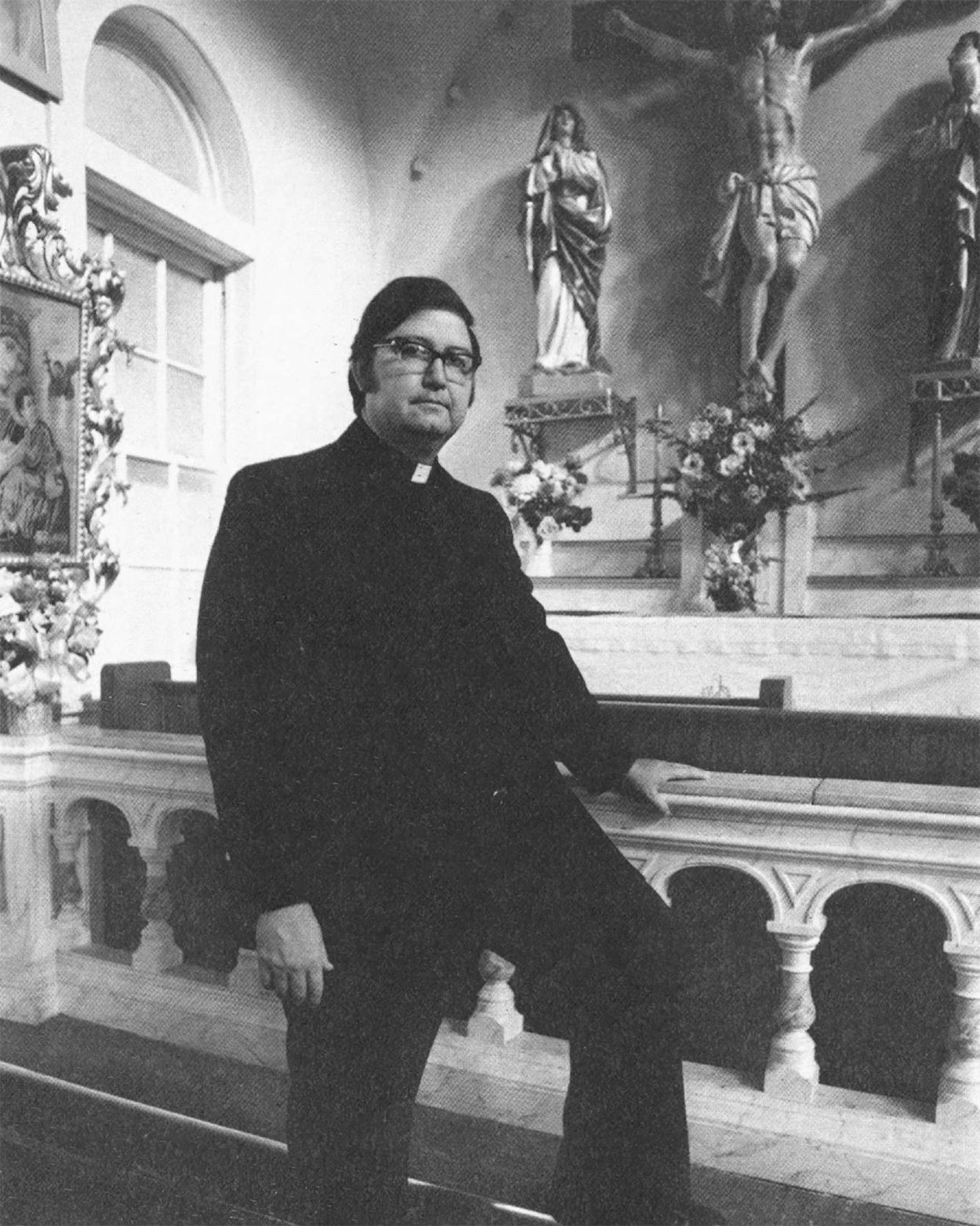

In the fall of 1973, about the time Charles Becker was busily killing snakes, Father Edmundo Rodriguez was listening to yet another plan for organizing San Antonio’s Mexican American community. A pudgy, gentle Jesuit priest in his late thirties, Rodriquez looked more like the ideal person for the part of Santa Claus in a secular Christmas pageant than a crusading reformer. But his visitor, himself a bulky 200-pounder, knew he had come to the right place. Working out of the fading red brick Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on the near West Side, not far from the old Missouri Pacific Railroad Station, Rodriguez had been active in numerous causes: U.S. Civil Rights Commission hearings in San Antonio, bilingual and bicultural committees, and a drive to get the Bexar County Hospital Board to respond to patient grievances. Equally important, Rodriguez was active in interfaith organizations and knew who might be willing to back their sympathy for the poor with cash.

Rodriguez wasn’t optimistic. There always seemed to be another social activist with a plan for organizing the West Side. He had watched them talk to people in the barrio about the obvious issues—racial discrimination, bilingual education, police brutality, unemployment—and had seen lots of heads nod in agreement, but somehow the organizers never made any progress. People didn’t seem to care, at least not enough to act.

Nevertheless, Rodriguez sensed that this one was different. His name was Ernie Cortes, he was a native of the West Side, and he had a solid grasp of how power worked in San Antonio. Furthermore, his bulk gave him an air of authority that made him hard to ignore. Cortes, thirty, had gotten his formal education at UT in economics, his political training on the Bexar County Hospital Board as an appointee of County Commissioner Albert Peña, and his practical experience as an economic development specialist for the Mexican American Unity Council. (It was as a member of the hospital board that he had first met Rodriguez.) Moreover, Cortes had received training earlier that year as a community organizer at the late Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago. Alinsky, a self-described radical whose goal was to bring power to the powerless, first came to national prominence in the thirties as a friend of labor boss John L. Lewis; he later organized Chicago’s Back of the Yards area (Upton Sinclair’s Jungle) and led the fight against Eastman Kodak on behalf of Rochester’s ghetto blacks. Alinsky was no idealist or social dreamer; he was a hard-core realist who wrote extensively about how to overcome the weaknesses of the poor by exploiting those of the rich and powerful.

“ ‘The trouble with this town is that it has too many old rich and too many new poor. They’re just alike. They’re lazy and idle and contribute nothing. Give me the nouveau riche every time.’ ”

All this Rodriguez knew. But what most impressed him was that Cortes didn’t seem to be just another hustler looking for no-strings-attached dollars from the church. He wanted money, to be sure, but Cortes agreed that it should come from an ecumenical sponsoring committee that would closely monitor the project and hold the staff accountable for the money. (Several San Antonio churches had already been stung by self-appointed organizers who had little to show for their efforts—including financial statements.)

Rodriguez agreed to try to raise the money. It wasn’t easy, but he was able to pry loose some contributions from Church of Christ, Methodist, and Episcopal sources, and to win the essential support of San Antonio archbishop Francis Furey. The money would be doled out in stages and could be cut off at any time. Only Rodriguez could sign the checks. The sponsoring committee, made up of churchmen from the donating denominations, was formalized in January 1974 and hired Cortes as the organizer at a salary of $16,000 a year. The movement was uninspirationally labeled the Committee for Mexican American Action, and Cortes went to work.

He started at the churches, asking pastors for the names of parishioners who were leaders, whether churchgoers or not. Cortes wasn’t interested in people who were active in politics; he was looking for those who organized church socials, ran PTAs, or perhaps were union stewards. Natural leaders, he called them: not people who were showy, but those who got others to show. He found a woman in a public-housing project who spent Saturdays cooking food for shut-in senior citizens; later, when the neighborhood organization tried to get a bridge across a creek for schoolchildren, she had no trouble getting people to turn out in support—they trusted her. He found Andy Sarabia, the chairman of the community life committee of Holy Family Church, who was already spending much of his time finding out what the parish could do about problems in the area. And he found Beatrice Gallego, a PTA leader and Head Start volunteer who was also involved with senior citizens and Catholic women’s groups. Cortes looked for anyone who had a following, and he found them in every Mexican neighborhood, people with no history of political involvement.

After identifying who to organize, Cortes’ next problem was to find what to organize them around. Instead of picking the obvious civil rights issues that had mesmerized previous organizers, Cortes took the simple but crucial step of asking his new contacts what mattered to them. The answers were startling: drainage, high utility bills, chugholes in the streets, sidewalks for their children. There was not a single mention of any of the more glamorous causes traditionally embraced by minority politicians.

Rodriguez was elated. It was, he said later, like one of those light bulbs that suddenly appears in cartoons. No wonder previous efforts had failed. They had been on the wrong track. The myth that Mexicans could never be organized, that they didn’t really care about social issues, had been repeated so many times he had almost begun to believe it himself. Many of his parishioners did believe it. But the problem had been with the technique, not with the people. It was so obvious; why hadn’t he seen it earlier? For the first time he allowed himself to think that this thing might actually work.

Cortes went from parish to parish during the winter and spring of 1974, recruiting leaders, weeding out the weak from the strong, researching issues, and setting up independent neighborhood groups organized around parish churches. It took him seventeen phone calls before Beatrice Gallego would even agree to a meeting. By the summer he was ready to take the crucial step: bringing the area groups together under one umbrella organization. Cortes and Rodriguez knew that this was where previous organizing attempts had been undercut by jealousies and personality conflicts. Certainly the potential was present for that to happen again. Neighborhood leaders would be vying for power in the central organization, and only a few could succeed. People who had spent their whole lives fighting for their own neighborhoods were suddenly going to have to shift their efforts on behalf of other areas. Yet without a strong umbrella, the local groups would have no clout. Projects like drainage were too big and too costly for one parish to attack.

Cortes and Rodriguez did the groundwork for the changeover. They taught their inexperienced troops that in politics, size is power. They explained about trade-offs: you help this parish get a park and they’ll help you get drainage. They promoted a merit system for leaders: those who produced rose higher; those who didn’t were limited. They talked to people about their fears and learned that most didn’t worry about losing jobs, or what their neighbors would think, but that they would be made fools of in public by people who knew more than they did. So Cortes helped them learn how to do research: where to look for answers and what to ask for when they went to city hall. The area leaders met in midsummer at a parish social hall to form their new union. There was a tense moment or two while the group debated what issues to focus on—a sizable contingent, incensed over spiraling utility bills, wanted to go to war with the city’s natural gas supplier, Lo-Vaca Gathering Company—but Cortes channeled the discussion toward whether anything could be done. Gradually, the group perceived, unhappily, that the utility crisis was in the hands of the courts, the Texas Railroad Commission, the Arabs, the energy companies, and, locally, the independent CPS (City Public Service) Board—none of which could be affected much by what some angry citizens in West Side San Antonio had to say. But drainage was different; it was localized, focusable, in the hands of a city manager, a city council, and, ultimately, voters, who had to approve bond issues.

The leaders settled on drainage (“We couldn’t tell them,” says Rodriguez. “It had to be understood and agreed on by the people themselves”), and Rodriguez breathed a sigh of relief. The center had held. Now it was time for a meeting with City Manager Sam Granata. But first, there was one more thing to do. That insipid name, the Committee for Mexican American Action, had to go. In a strategy session for the confrontation with city hall, someone jokingly suggested the name COPS: “You know, they’re the robbers and we’re the cops.” Someone else, still bitter about those utility bills, pointed out that “PS could stand for public service, just like CPS, only we really mean it.” and the group that would fill Charles Becker’s power vacuum had its name.

Ask and Ye Shall Receive

When Ernie Cortes called, Beatrice Gallego knew what he wanted—word passed quickly on the West Side, even though nothing had appeared in the news media about Cortes’ organizing efforts—but she didn’t want to talk to him. She had heard it all before, young radicals talking about confronting the system, full of socialism and kill the gringo, trying to convince her that she should get involved. Get involved! What about Head Start, the PTA, the church, substitute teaching? Those were the things that really mattered; who cared about another march to protest police brutality? There wasn’t any time left for politics, even if she’d been inclined that way. Besides, like most of the women she knew, even the most active, she considered home her first priority—her three children and her husband Gilbert, a hardware salesman who had built their house in a modest middle-class neighborhood called Palm Heights.

There was another reason she didn’t want to talk to Cortes. The whole idea of radicalism appalled her. The youngest of seven children, she had wanted to be a nun until she met her future husband. Like many Mexican Americans, she had been raised in a strict family atmosphere and been instilled with a respect for authority (though occasionally her father shocked her with bitter complaints about the city’s Anglo leadership and their neglect of the West Side). Long after her name had become a household word in San Antonio political circles, she recounted to him a small victory she had won at a public hearing New Braunfels Congressman Bob Krueger had arranged to hold in San Antonio. As she described Krueger’s reactions, her father interrupted his youngest child, “Baby, did you call him Krueger? You shouldn’t say that. He’s Congressman Krueger.”

At the urging of a priest, Gallego finally met with Cortes. He asked her about problems in her neighborhood. “I had to laugh,” she recalls. “What wasn’t a problem? We had no drainage, no sidewalks, no curbs, no parks, we were cut in half by an expressway, we didn’t have enough water pressure to water the yard and draw bath water at the same time.”

She was still skeptical, though, as the fledgling organization prepared for its showdown with the city over drainage. COPS tried to arrange a West Side assembly with Granata; he refused to come. So they took their plea for a meeting to city hall, jamming into the small council chambers in such numbers that one councilman was reminded of Travis’ famous message from the Alamo: “I am besieged with a thousand or more of the Mexicans.” The council took one look at the crowd and ordered Granata to meet with the West Siders. The session was set for August 13, 1974, at a West Side high school.

Cortes and Rodriguez were worried about the upcoming confrontation. They knew that turnout was critical; COPS had to make a good showing. More important, they wondered whether their people were psychologically prepared for what lay ahead. Most, like Gallego, had been brought up to respect authority. The Alinsky approach did not require breaking the law, but it did not shirk from bending it a little. Its guiding principle was to encourage and focus the latent anger of the poor by showing how the system worked against them. But everything was predicated on that anger; it had to come naturally. Just how angry were these homeowners and churchgoers? Angry enough to forget their upbringing? Angry enough to implement the Alinsky tactic that “ridicule is man’s most potent weapon”? Angry enough to overcome the lack of confidence and fear of ignorance they all were sure to feel? Another of Alinsky’s cardinal rules was “Never go outside the experience of your own people.” Was militance itself a violation of that rule?

Cortes did the best he could to prepare his people. At training sessions they rehearsed the confrontation, anticipated the double-talk bureaucrats excel at, and drilled on pinning the city manager down to yes or no answers.

Poor Sam Granata. Not only was COPS laying for him, but also the sky was about to fall on him. On August 7, just five days before the meeting and practically a year after the destructive 1973 rainstorm, the heavens opened again. Forty families were forced out of their homes, and on Inez Street floodwaters drove an old woman with a 105-degree fever out into the mud. A bridge across the Mayberry ditch caved in, and streets all over the West Side were impassable. COPS didn’t have to worry about the turnout anymore; 500 angry people showed up. “That bolstered our faith in God,” said Sarabia of the rain.

Granata was greeted with slides showing typical West Side scenes after a storm. The city manager was on the defensive from the start. COPS researchers had uncovered histories of drainage projects that had been authorized by the council but never funded—the Mayberry project had been part of the city’s master plan since 1945—and others that had been funded in bond elections but never implemented. COPS wanted to know why, and the only answer the beleaguered Granata could come up with was “We dropped the ball.” In the audience, Beatrice Gallego could hardly believe what she had heard; her last doubts about COPS’ tactics melted away. The authorities weren’t so smart after all. Why, COPS knew more about drainage than the city manager! These people weren’t worthy of her respect. Now she was angry. Granata made matters worse by lamely defending the city’s inaction with an explanation that would come back to haunt the city: “If you want something, you have to ask for it.” Beatrice Gallego vowed to herself that no one would ever have to say that again. She went home that night and started drawing up lists.

Granata’s ill-advised admission that San Antonio government operated by the squeaky-wheel-gets-the-grease method did more to politicize COPS’ membership than all their careful training.

It exploded the myth most of them had accepted for years—that the city in its wisdom would take care of them in good time. The battle lines were drawn for keeps.

The aftermath of the Granata confrontation was immediate victory. When he refused to promise any action on drainage, the meeting ended in a shouting match, and COPS returned to the council chambers. Becker, who eventually would turn against COPS when the organization began sniping at developers, professed astonishment that the Mayberry project had been neglected for thirty years and told the city staff to come up with a plan for financing it. That fall the council drew up a $46 million bond issue that passed in November—the same month that COPS held its first annual convention, formalized its structure, and elected Sarabia president.

Perhaps more than any other person in COPS, Sarabia epitomizes the idea of a natural leader. When he talks about city politics, his eyes bore into you like lasers, with the fierce intensity of focused anger. He is outwardly calm, with none of the gestures of the polished speaker, but the listener is transfixed by the eyes. It is only later that you realize he is quiet and soft-spoken. He seems to shout without raising his voice.

“We got into COPS because we cared about our neighborhoods,” he recalled recently. “We weren’t looking for any handouts—we’re taxpayers, and we found out our tax money wasn’t working for us. They’d promise us projects and then they’d use the money for something on the North Side. We found case after case of it. It made us angry. Then we found that they were incompetent. When you learn something emotionally, I guarantee you, you never forget it.

“You’re educated to become one of them. If you want to make it, you have to leave your neighborhood, move to the North Side, forget what you left behind. It doesn’t just happen; the city’s policies are planned that way. Ignore the old, subsidize the new. But what if you don’t want to move to the North Side? What if you’d like your children to stay in your neighborhoods?”

COPS invited the city council to its first annual convention so they could learn about the needs of the neighborhoods. None showed up, so COPS decided to go over their heads to the symbolic leaders of the business community. They tried to arrange a meeting with the head of Joske’s (“We had lots of charge accounts with him, so we assumed he’d help us,” said Sarabia, who is no longer so naive as to assume anything of the sort). The counteroffer came back: would Sarabia meet him alone? No deal. Sarabia took 200 people to Joske’s, and they spent hours examining fine dresses, trying on expensive coats, asking sales personnel about jewelry—and buying nothing. With 200 Mexicans and a half-dozen TV cameras clogging the store, Joske’s didn’t do much business that day. The next day Sarabia led the group to the Frost Bank, the city’s largest. Again they broke no laws but merely lined up at tellers’ windows to exchange dollars for pennies, then moved to the adjacent window to trade pennies for dollars. Upstairs, Tom Frost, Jr., agreed to meet with a COPS delegation, admitted they had legitimate complaints about the way the city had neglected their neighborhoods, but declined to say it publicly. The next day, however, the head of the Greater San Antonio Chamber of Commerce appeared at COPS’ shabby West Side headquarters. All he learned was that next time he’d better make an appointment first. Cortes refused to see his unannounced visitor.

Not surprisingly, the tie-ups caused a storm of protest in the city about COPS. Bewildered North Siders couldn’t understand what these people wanted; hadn’t the city responded to their requests with a bond issue? They didn’t understand that COPS was interested not just in projects but also in power—a permanent share of the decision-making process. But not all the protests came from the North Side. One Mexican on the West Side recalled her reaction to the tie-ups: “I couldn’t believe the church was involved. They’re always saying, ‘Mind your manners.’ How could they support such things? It was just horrible, walking over people like that. I can’t figure out to this day what made me change my mind and join COPS.” But she did.

Who Are Those Guys?

Occasionally there are moments that capture perfectly in one insignificant incident the unending historical tension between past and future. Such a moment came to San Antonio in early 1975 at, of all places, a hearing on how the council should spend $16 million in federal funds. COPS was there in force, with more than 200 supporters, presenting its case for putting the money into old neighborhoods for parks, drainage, and streets. But Mrs. Edith McAllister was there too, the daughter-in-law of the ex-mayor, soliciting $300,000 for the San Antonio Museum Association to renovate the old Lone Star Brewery. It was clear that COPS didn’t think much of her request when there was water standing in the streets, and it was equally clear that she didn’t really comprehend why all these people were up in arms. How could she make them understand? She summed up her plea to the room: “Man does not live by sewers alone. He also needs museums.”

From the beginning Anglo San Antonians have had a difficult time understanding just what COPS is. Their perplexity is understandable, because COPS is an organization built on paradoxes and contradictions. It is a radical organization made up of people whose personal style is intensely conservative. It is a political organization made up of people who have no use for politicians. It is an organization made up mostly of Mexican Americans, but it has nothing to do with traditional ethnic issues.

Yet someone with as long and proud a record of public service as former Mayor McAllister can say, in all seriousness, that “I haven’t got any use for a communist organization.” And lest that be interpreted as just the bitterness of an 88-year-old man, John Schaefer, one of the city’s leading developers and the chairman of the City Water Board, says, “To be kind to them, I’d say they’re socialist. Their philosophy is straight out of the communist manifesto: from each according to his means, to each according to his needs.” A local oilman has a somewhat more charitable view: “They’re just looking for a handout. I bet most of them are on welfare.”

In fact, most of them detest welfare. Carmen Badillo, COPS vice president, tells how her father bought cheap land near a creek rather than go into a housing project. The home cost $2500 and consisted of four walls—he had to build the inside walls himself—no sewers, no running water; it took him twenty years to pay for it. But it was better than public housing. “There are a lot of people on welfare who shouldn’t be,” she says. “It’s gotten to be the thing to do. But it’s wrong. It robs you of your dignity. Welfare people don’t participate. They don’t get angry.” So antagonistic is COPS toward handouts that its charter bars the organization from accepting federal funds. (Although in its early years COPS relied heavily on religious foundations, it is now entirely self-sufficient, financing its $100,000 annual budget through dues and an advertising booklet that brought in $47,000 in four weeks.)

As for economic philosophy, the COPS ranks are not exactly crawling with Marxists. A case can be made—as one area leader said—that “we’re more conservative than Tom Frost.” (Frost, who actually has considerable respect and admiration for COPS—“They’re good people and they’re good for the city,” he says—seems to be the organization’s favorite symbol for the Anglo power structure, even though he cannot accurately be called a power broker.) “Let me tell you what kind of free enterprise system they believe in,” says Andy Sarabia. “It’s only free for themselves. Our taxes pay for their free enterprise.”

Most Anglos have been unable to make the distinction between radical tactics, which COPS enthusiastically embraces—shouting, intimidation through numbers, rudeness, threats of mass action against politicians and financial institutions—and radical people, which it should be obvious by now are few and far between in COPS. Some might say there is no difference, but that is a terribly shortsighted view with terrible consequences for San Antonio. For there are Mexicans in town who do not share COPS values, who, though they do not use radical tactics, do aspire to control the city in a way COPS does not.

One of the things least understood about this organization is its contempt for politicians—all politicians, Mexicans included. Before major elections COPS holds “candidates’ accountability nights,” when office seekers are asked to give their views on issues COPS regards as crucial. COPS permits only yes or no answers—a tactic not so admirable when practiced by, say, the AFL-CIO, but the difference is that both COPS’ issues and its membership are broader based than the usual pressure group’s. And while there is much disagreement in town over COPS’ tactics, there is no dispute over its power at the polls. COPS will not endorse particular candidates, but it will raise unholy hell about those who openly oppose their goals. One unfortunate Mexican politician came to accountability night a little too full of booze and macho; he said no to their questions and they walked the streets to beat him at the polls. On two important citywide referendums—one over halting development on the Edwards Aquifer northwest of town, the other on single-member city council districts—COPS showed its muscle when both propositions passed. During the single-member districting election, word got out at midafternoon that the West Side turnout was too light and in three hours of working door-to-door, COPS boosted the turnout high enough to help districting squeak through by 2000 votes.

The only people in town who seem to have figured out that COPS has no political ambitions beyond its issues are the politicians themselves. Several councilmen complain privately (they wouldn’t dream of saying so publicly) that COPS never gives any credit to politicians who help with their projects.

As an organization, COPS views all politicians as the same. “A politician is a politician,” Gallego is fond of saying; they would all rather make a speech than a commitment. Undoubtedly there are COPS members who emotionally would like to see the city elect a Mexican American mayor, but once the votes were counted, ethnic ties would make no difference. Earlier this year COPS attacked the Anglo majority on the school board for voting to spend $1.6 million on a new administration building instead of refurbishing rundown schools; the April elections produced a Mexican majority and COPS promptly attacked them on another issue. That produced a phone call to COPS the next day: “What’s the matter with you people? Don’t you realize we have to stick together?”

Of all the things about COPS, this disinterest in personal or ethnic political power is the hardest for other San Antonians to believe. Many people thought that when Sarabia voluntarily gave up the presidency last year (to be succeeded by Gallego), he was preparing to run for county commissioner. He didn’t, he says, “because then I’d have to face all these crazy people.” Sarabia talked about why he could never have switched over to politics:

“If anyone really thought that, it proves they didn’t understand COPS. Politicians don’t matter—people matter. The whole basis of this organization is a tremendous faith in people.

“Can you imagine what it was like in the beginning? Nothing was easy. We got calls in the middle of the night: ‘Why don’t you go back to Mexico?’ We were awed when we went to city hall. We didn’t know anything about a single issue. All we had was our own anger—and trust. COPS started as a blind trust; it was built on trust. Now no one wants to violate it.”

“Let San Antonio Grow”

High up in one of San Antonio’s tallest bank buildings, The Lawyer made it perfectly clear he didn’t trust COPS. He had tried to understand them, tried to deal with them, but it was useless. He had even suggested that his clients, some of San Antonio’s biggest land developers, read Alinsky’s manual Rules for Radicals, but demand was so high local bookstores couldn’t keep it in stock. Meanwhile, COPS kept attacking his clients even more fiercely.

“I can’t understand it,” The Lawyer said. “There’s only one answer to the West Side’s problems, and that’s better jobs. Who else in this town besides the developer pays double the minimum wage? If we don’t build houses, what’s left here economically except the military.”

The Lawyer proceeded to reel off a dismal litany of statistics. Houston’s building permits are up 40 per cent; San Antonio’s down 2 per cent. San Antonio’s unemployment rate is twice that of Dallas. Houston has 122 home-based companies listed on the New York and American stock exchanges; industry-poor San Antonio by comparison has only 11. Manufacturing accounts for only 13 per cent of the labor force, compared to 27 per cent nationally; almost all of that is concentrated in products for local use, or in the needle trade—businesses that pay minimum wage: $2.30 an hour, $92 a week, less than $5000 a year. More than one job in four is on a government payroll; only Washington, D.C., has a higher percentage. The federal government alone accounts for a third of San Antonio’s total wages. The picture is not a good one, nor, says The Lawyer, is it an accident: “Before we got involved in politics, there was nothing here. The dumb bastards that ran this town did everything they could to keep industry out and build a wall around this town. They didn’t want outsiders here.”

One outsider they particularly didn’t want was Henry Ford. Long before World War II he wanted to build an automobile assembly plant in the city, but the local gentry didn’t exactly greet him with open arms. It is said that they tried to snooker him on the land deal and otherwise made it known he could take his factory and his labor unions elsewhere without being terribly missed. When Ford finally realized he wasn’t wanted, the story goes, his parting shot was “You people are crazy.”

But the business leaders of that era didn’t care. After all, the banks were full of cattle money and oil money—but no one stopped to consider that little of it ever seemed to be plowed back into San Antonio. Instead it was invested in the oil patches and grasslands of South Texas. Its owners had no stake in the city’s economic vitality. The economy came to rely increasingly on the military—another group, like cattlemen and oilmen, without a permanent stake in the community. No one paid much attention in 1933 when a small company named Frito picked up and moved to Dallas; no San Antonio bank would advance it the capital for expansion, so it had to look elsewhere. But the loss of that company, which now employs 17,000, typified the complacent attitude of the business leadership. True, the city made some nominal efforts to attract industry—the council even voted tax dollars to help support the local Chamber of Commerce—but the Chamber was dominated by merchants who benefited from the abundant supply of cheap Mexican labor. When a new plant was lured to the city, it usually turned out to be something like Levi Strauss, another nonunion minimum-wage shop. And despite the city’s gloomy economic statistics, some of the city’s leading figures, like former Mayor McAllister, still maintain that San Antonio shouldn’t go after heavy industry.

“We broke that up,” The Lawyer says. “Anything’s possible here now. Where do you think COPS would be if we hadn’t opened things up? I can’t figure out why they hate us.”

The Lawyer leaned back in his chair, locked his fingers behind his head, and inspected the ceiling through fashionably large glasses. “The trouble with this town,” he summed up, “is that it’s got too many old rich and too many new poor. They’re just alike. They’re la-zy and i-dle”—he drew out the first syllables contemptuously—“and contribute nothing. Give me the nouveau riche every time.”

There was a time, when the GGL was falling apart in the early seventies, that astute San Antonians involved in politics thought the alliance of the future would unite the Hungries (Anglo developers and Mexican West Siders) against the Satisfieds (old families and downtown interests). Similar coalitions have sprung up in other cities—Austin, for one, where ethnic minorities broke with the no-growth policies favored by students and other liberals. But such predictions reckoned without COPS.

Once COPS realized that money had been diverted from projects planned for older parts of town, they looked to see where it went. They found, for example, that the widening of Pleasanton Road, a major South Side artery, had been approved in a 1970 bond issue—but when the road builders went to work, it was San Pedro Avenue on the North Side that got their attention. More often than not, that was the pattern: the diverted funds went to build a water main extension to a new subdivision, to pave streets or build drainage systems in the newer parts of town. Issue after issue came down to who would get the money, new or old, and it became clear that city policies, intentionally or not, usually favored the new. The consequences were obvious: people wanted to live where the roads were, where the drainage was, where the money was spent.

Other city policies benefitted not just suburban areas generally, but their developers. COPS was particularly outraged at City Water Board procedures, instituted after developer John Schaeffer became chairman, that called for the city to provide auxiliary water main materials free to subdividers. The materials may have been free to developers, COPS protested, but not to inner-city taxpayers who continued to cope with substandard mains and low water pressure while their tax dollars were handed out to developers in the form of subsidies. Furthermore, COPS noted, developers were supposed to reimburse the city for the much larger suburban mains the city built out to their subdivisions—but in practice both the developers and the city generally ignored the debt. That, of course, amounted to another subsidy. Now COPS had the ammunition to challenge the most basic of assumptions about the modem city: that the decline of the core and the sprawl of the fringe are inevitable.

So the developers became the enemy. They were in power; they were the ones shuffling money around to encourage growth outside of town. Nothing underscored their attitude—and their power—more clearly than their reactions to a study by an upper-level city planner suggesting that all growth in San Antonio for the next 25 years could take place within Loop 410. During a public hearing, a developer on the city council threw a copy in the trash can, proclaiming vehemently, “That’s where it belongs.” Soon the author was canned too.

The feud between COPS and the developers broke into the open in July 1975 when 250 shouting, boisterous COPS supporters jammed a small room at the City Water Board to protest a proposed rate increase. But COPS wasn’t there just to protest; its style is always to have an alternative. Stop subsidizing developers—make them pay for their own water mains—COPS said, and you won’t need a rate increase; and they hauled out facts and figures to back it up. Eventually the board agreed to change its subsidy policies and consented to a compromise on the rate increase. COPS had proved that it was not just a powerful neighborhood organization, but a force to be reckoned with citywide.

A few months later COPS successfully challenged the developer crowd again. The city council narrowly voted to buy a suburban golf course from a developer for a price considerably above appraised value; for added controversy, the council planned to finance the deal with federal funds earmarked for the inner city. Beatrice Gallego vowed publicly that if the purchase went through, she would make a national scandal of it. The city was spared when COPS was instrumental in getting federal officials to veto any diversion of the funds.

But even more important than the individual victories COPS was winning was the political change that was taking place in the city as a whole. People were getting fed up with the developers. Subsidies, sweetheart deals, insider transactions, stacked boards and commissions—COPS had helped put San Antonio city government under the microscope and people didn’t like what they saw. The developers suffered an overwhelming defeat when COPS and Anglo environmentalists forced a referendum on a council decision to allow construction of a shopping mall over a thin slice of the Edwards Aquifer northwest of town. Environmentalists managed to portray the fight as a clean water issue, but Cops knew the real issues were growth and power. Voter turnout trebled expectations, and the developers—who had run newspaper ads warning that COPS was trying to take over the city—were routed by a 4–1 margin. The developers’ brief rule was in serious trouble, and suddenly they began showing up at council meetings wearing buttons pleading “Let San Antonio Grow.” But they were finished. A year later, in March 1977, another referendum ushered in single-member council districts and in the April election, developers were routed all over town: their candidates were beaten not just on the West Side and South Side, but North and Southeast as well.

Curiously, despite the fact that COPS has publicly insulted them and contributed greatly to their loss of political power, some developers hold a grudging admiration for COPS—much more than for the old guard that once ran the town. Perhaps it is because, despite Anglo fears of an ethnically divided city, there is still a large reservoir of goodwill in San Antonio. John Schaeffer—though he considers Sarabia “definitely radical,” thinks that COPS is “out to take over the city,” and says COPS members have threatened him personally—nevertheless bought a $1000 spread in COPS’ fund-raising ad booklet this summer. Jim Dement, who helped finance Charles Becker’s 1973 mayoral campaign and this year made an unsuccessful council bid himself, is similarly ambivalent. He accuses COPS of “fostering hatred and real problems,” but he concedes, “They had to do something drastic to get the attention of the public.” And he adds, “I see dedication to San Antonio that wasn’t here three years ago. There’s more hope and conversation in this town than in a hundred years. And I love it. This is a town where you can have nothing and be somebody. Now don’t tell me COPS is bad.”

A Call to Arms

On a warm October night Henry Cisneros interrupted dinner with an old friend to speak to one of several Anglo citizens’ organizations that have sprung up in San Antonio with hopes of emulating COPS’ success. It had not been a good week for bridge building—the council had split twice along ethnic lines amid much controversy—and Cisneros was a little nervous.

It was a Friday, so a lot of parents and most of the students were at high school football games. Nevertheless, about forty members of the CDL (Citizens for Decency through Law) showed up at a small church to hear Cisneros talk about the spreading menace of pornography in the city. It is an issue that truly outrages Cisneros—a few days earlier he had walked into a West Side convenience store with his two young daughters to discover a tabloid on the counter featuring the story How to Rape a Woman—but despite this affinity between speaker and audience, something didn’t click. Cisneros can call on a pretty rousing speaking style, but on this night he was subdued, content to rely mainly on homilies that are the ultimate refuge of every politician. He closed with a rhetorical question—“What can a small group of people do?”—but it soon became apparent that this small group of people was unlikely to do very much.

Someone asked Cisneros, “What can be done by the city council?” and he quickly flipped the ball back: “You people who have studied and worked on the problem need to come up with a plan to present to the city.” Hah! COPS would never have let him get away with that. They would already have had a plan. Then someone complained that the Witte Museum was displaying pictures of naked women. Cisneros bravely tried to point out that political organizations are more effective when they stick to things a large number of people can agree on, but the zealots persisted. It was another mistake COPS would never have made, another trap they would have avoided. It is inconceivable, for example, that COPS would embrace a cause currently popular among Hispanics in the U.S. Northeast: bilingual law courts. COPS stays sighted in on targets that are carefully chosen—so carefully chosen that in a recent poll, 70 per cent of San Antonians said they agreed with COPS goals, despite the general unpopularity of COPS tactics.

Finally a white-haired lady at the back of the room caught on. “I don’t approve of COPS,” she told Cisneros, “but they certainly know what they’re doing, don’t they?”

They do indeed. The truth is that the CDL felt the same anger about pornography as COPS felt about drainage.

It is a fair guess that everyone at the church that night was more affluent and better educated than 99.9 per cent of COPS’ members. Yet, if that meeting is any indication, CDL is unlikely to approach COPS’ success. COPS has managed to do the one thing that is essential to success in politics—or in business, athletics, or just about anything else. It has discovered the elusive formula of how to build an organization that works.

Not that anyone would want to use COPS’ organization chart for a model. It looks like a map of the New York subway system. Technically COPS is an organization of organizations—the only time individuals are counted is when attendance is added up at the annual November convention—but no one can say for sure how many groups are part of COPS at any one time. It depends on the issue and who’s paid dues recently. Right now there are 33 primary organizations, known as locals, with another three or four on the periphery. Most are Catholic parishes (which on the West Side is the same thing as a neighborhood organization, since neighborhoods there are defined by parish boundaries), but there are also block clubs and churches from other denominations: a small Anglo COPS chapter in the northeast, which joined because the area couldn’t get city help for their drainage problems, and a growing black East Side COPS group.

Each local is virtually autonomous in choosing its own neighborhood issues. If, for example, Andy Sarabia’s Holy Family local wants a park, a footbridge for schoolchildren, or some vacant lots cleared of weeds, it plans its own research and strategy—though obviously its chances will not be hurt by operating under the COPS banner.

There has to be a central organization, however, to set policy, raise money, and hammer out compromises on citywide issues like drainage priorities. COPS has managed to come up with a structure that allows everyone to take part without hampering the ability of a few skilled leaders. How this works is too complicated to be explained in detail, but it involves an executive committee (composed mostly of citywide leaders), a steering committee (composed mostly of neighborhood leaders), and a delegates’ congress (composed of any member of a COPS local who shows up to vote). In theory the committees recommend and the delegates ratify, but in practice the power lies with the committees. If this sounds too labyrinthine, try substituting management, directors, shareholders, and General Motors for executive committee, steering committee, delegates’ congress, and COPS.

One important omission from this bureaucracy is the Alinsky-trained organizer. This is no oversight. The organizer’s primary job is to spot new natural leaders in the community—to provide the group with a continuing supply of new blood. In the beginning, of course, Ernie Cortes did that and far more: he plotted strategy, helped lead actions, trained the Sarabias and Gallegos and other emerging leaders. It was too much, and to his credit Cortes had the wisdom to see it; to last more than a year or two, COPS had to be run by the people themselves. So Cortes left for Los Angeles in August 1976, to be replaced by someone who is as different in temperament and background from Cortes as Cortes is from Tom Frost. Cortes is from San Antonio, Mexican, and Catholic; Arnie Graf, his successor, is from upstate New York, Anglo, and Jewish, and for that matter doesn’t speak a word of Spanish. Nor was Graf well versed on COPS’ central issue. When he was interviewed by Beatrice Gallego, she inquired what he knew about the 39 Series; all he could think of was, “Didn’t Cleveland win?”* She was asking about drainage, not baseball, but Graf’s record as organizer of a white working-class Milwaukee neighborhood eventually carried the day and got him the job.

The Alinsky connection is probably the least understood, and most feared, aspect of COPS among San Antonio’s Anglo community. Many see it as the cause of the trouble. They pointedly mention that Father Rodriguez, Sarabia, Gallego, and other COPS leaders have gone to the Industrial Areas Foundation for training, and former Mayor McAllister bluntly calls the IAF “Saul Alinsky’s communist school in Chicago.”

Arnie Graf chuckles at the unlikely sight of Beatrice Gallego, mother of Miss Teenage San Antonio, earnestly watching a demonstration of how to make Molotov cocktails, or studying the Bolshevik Revolution. “Most businessmen could go to Chicago and get something out of it,” Graf says. “You learn how to read a city budget, how to deal with the news media.” Rodriguez says the most important subject is how to run a meeting, for that is where most organizations fail—either by having the same people make all the decisions, or by falling into endless unresolved debate. So the IAF teaches such mundane skills as how to plan and stick to an agenda, and how to resolve an issue.

No, the Alinsky connection was not the secret. At most it provided a useful frame of reference. Far more important were factors unique to San Antonio. There were breakdowns in city services that even the most sheltered Anglo could agree were inexcusable. There was a power vacuum in the city’s leadership, so no one could mobilize to stop COPS when it was still vulnerable. Many COPS leaders like Andy Sarabia held civil service jobs and were immune to Anglo threats of economic retribution. San Antonio’s ethnic minority had just become a numerical majority, so the old argument that Mexicans were powerless no longer had any validity. And most important, COPS had the Church.

It was as much a marriage of convenience as love at first sight. The Church has traditionally maintained a paternalistic attitude toward its Mexican American subjects. Only seven local Mexican American priests have been ordained in the San Antonio archdiocese in 250 years. Many priests never mastered Spanish, still the lingua franca on the West Side. Then, after Mao booted Belgian missionaries out of China, many came to the West Side in search of other downtrodden subjects. But by the seventies things were changing. Protestant denominations had been the great force for social reform during the civil rights fights of the sixties, but the Catholic Church was catching up. In San Antonio, as the West Side continued to deteriorate and young people moved to the North Side, it became obvious that the economic self-interest of the parish church lay in keeping the neighborhood up. San Antonio is not a rich archdiocese; there would be no help from the hierarchy. So COPS became not only good politics but also good religion.

The support of the Church was the crucial factor that got COPS started and kept it going. The Church was the only institution in the community that had the widespread allegiance of the people. It provided a financial base and a sense of permanence. It was a reservoir of leadership talent, and a way for people to keep in touch. But most of all, it gave COPS something no previous movement had had: a stamp of legitimacy. That is why even today the average COPS member would rather be led into battle by Father Albert Benavides, a fiery, immensely popular West Side priest, than any other COPS leader, even Gallego or Sarabia.

The role of the Church points the way to another of the reasons for COPS’ success. The organization draws on the inherent strengths of the Mexican American community—qualities like loyalty, belief in basic values, and a love for family. COPS is a family, an extended family in the Mexican tradition. This pays off in unexpected ways: when COPS speakers approached the podium during early confrontations, the audience, without coaching, crowded around them to give moral support. They knew how awed their leaders were by symbols of power, but of course the council or the water board didn’t; to them these tactics smacked of intimidation. That was fine with COPS—these moves became part of the game plan.

For all of its strengths and successes, COPS is approaching a critical phase in its history, one that may well test the ability of the organization to endure as a political force. Its leaders have chosen to tackle the most basic—and most elusive—of all issues in San Antonio: economic development. They have had enough of the traditional San Antonio wage scale, skewed toward the minimum wage and ranking far below the other big cities in the state. They want to bring high-paying industries to the city and they want them located near their neighborhoods, not far out on the North Side.

This will prove to be a very different fight than anything COPS has undertaken before. In the past the battle was in the political arena; COPS was dealing with people who at least nominally answered to them. There was always the ultimate weapon of the ballot box, as more than one candidate found out to his sorrow last spring. But in economic development the enemy is better insulated. At an October training session, COPS area leaders stood beneath a wall chart eight feet high listing the names and positions of the members of the elite Economic Development Foundation that is practically a roster of the San Antonio establishment. It includes bankers, downtown businessmen, and developers, who together have personally chipped in $1.5 million in the last three years to bring industry to San Antonio—mostly without success.

COPS leaders are convinced that the EDF, like the businessmen who ran off Henry Ford, prefers smaller industries that are harder to unionize and won’t upset the wage scale. Cheap labor is also a useful selling point to counter fears of runaway utility bills. The EDF vigorously denies pushing cheap labor (“Who says that?” asks Tom Frost. “We don’t. I’ve been there. That’s the worst thing you can say. Plants want skilled labor”), but someone neglected to tell the EDF’s consultant to soft-peddle the cheap labor issue. In a secret report COPS somehow managed to sneak a look at, the consultant warned the EDF “not to attract industries that would upset the existing wage ladder.” All the evidence indicates that the EDF is following this advice to the letter. For example, the report carefully identifies the high-wage and low-wage sectors of the metal industry; one of the EDF’s proudest acquisitions, Bakerline oil tool supplier, matches the description of a cheap-labor operation.

But the issue may be moot, says Frost. “Asking me if I want heavy industry is like asking a man dying of thirst in the desert if he’d like a beer when there isn’t one for a thousand miles. Sure I’d like it, but we can’t get it. That kind of industry locates near markets, transportation, and water, and we haven’t got any of them.”

COPS, of course, disagrees (and so, for that matter, do some of the hustlers on the EDF itself, like developer Jim Dement). But what galls COPS above all else is that the EDF, which is the primary group trying to attract business to the city, conducts all its business in secret. No one in the city outside of the membership has a voice in anything the EDF does. “It is our future they’re determining,” Gallego told the COPS training session, “and they should be determining it out in the open.” So COPS is committed to bringing the EDF out of the closet.

That almost happened a year ago—or more precisely, COPS was invited into the closet. A well-intentioned EDF member offered to put up $20,000—then the price of two memberships—“so that underprivileged groups on the Mexican American West Side and the black East Side can become part of the economic efforts for progress.” But the affair was bungled from the start. The offer was made in the press rather than in person; its tone was insulting; and it smacked of tokenism. Sarabia rejected the offer, also in the press, by announcing that “COPS is not for sale,” and added scathingly, “By the way, we don’t consider ourselves underprivileged, because we have the will to fight for our dignity. We think they’re underprivileged.”

Everything about the coming battle with the EDF points to a tough struggle. The issue is a hard one to grasp; it is hardly as easy to understand as, say, water in the streets. The first COPS training session did not go well; the area leaders were slow to respond to Gallego’s attempts to draw out their feelings. Finally Sarabia, exasperated, stood up in the corner of the room. He scolded them for their lack of anger—some were even making jokes—and asked, “Don’t you know what cheap labor means? They’re talking about you. Our kids can’t find a decent job here. All they talk about is going to Houston or Dallas.” That subdued things for awhile, but the feeling still filled the room that this was going to be a long, long fight. One important stratagem of an organization like COPS is to keep morale up by pointing to a continuing series of successes. That is possible with drainage, but how do you show results in economic development? Even if COPS can remove EDF’s cloak of secrecy, that still doesn’t produce one plant or one job. The economic cards, as Frost suggests, may be stacked against the city—and even if they aren’t, even if COPS succeeds as it has before, the rewards may not trickle down to the neighborhoods for a dozen years.

For once COPS may also have the wrong side of the timing. The organization is entering a transitional phase, with the original leaders gradually turning over the reins to new recruits. Perhaps it is too early to say, but the second generation doesn’t appear to have the intensity or the ability of the first. Gallego and especially Sarabia are remarkable people who have an almost mystical empathy with their constituency. No one coming up seems to have that. The theory of organizations like COPS is that people grow with their responsibilities, so perhaps someone will develop. But some of the newer COPS people seem to lack that most basic of ingredients—anger. Maybe that anger is only possible for those who remember the beginning; maybe COPS has grown fat with too many successes.

The most serious threat to the future of COPS, though, is the one least within its control. It is the pace with which San Antonio is rushing toward ethnic politics. The Mexican political clique, shut off from power all these years, finally got a base when they took over the San Antonio School Board last April; their first action was to fire the district’s longtime Anglo lawyers and replace them with Mexicans from their own crowd—who took exactly one month to raise the district’s legal fees astronomically. The targets for 1978 include the district attorney’s office and a northwest San Antonio state senatorial district. Then there are the true Mexican radicals, a small but disproportionately vocal segment of the community, who also have a power base in the form of a couple of council seats. To both groups, ethnic political control of the city is the primary issue, and the more noise they make about it, the more the North Side is coming to view that as the sole issue too. And even though that is the one thing COPS does not care about, it may be COPS that suffers most.

The first shots in the Second Battle of the Alamo could be fired in January, when the city votes on a bond issue that contains many of COPS’ pet projects—too many, some North Side critics are already saying. The numbers aren’t encouraging: despite the fact that San Antonio has become a majority Mexican American city, the bulk of the voter turnout is still concentrated on the North Side. That could be fatal to the bond program’s chances, and developer Jim Dement, for one, doesn’t think it has a hope of passage.

No matter how the vote turns out, ethnic tensions are sure to be exacerbated. What if COPS loses? Make that loses again, for a COPS-backed school bond proposal went down to defeat by less than a thousand votes last spring. When the crunch comes, will COPS vote issues or race—and if it sticks to issues, will anyone listen? San Antonio in all likelihood is in for some rough years ahead, and the direction it is moving does not augur well for COPS. In the ethnic politics of the late seventies and early eighties, the “radicals” of today may well become the conservatives of tomorrow.

But even if COPS never accomplishes another thing, its legacy is indelible. Long after time has dulled the recently laid concrete on the storm drains and sidewalks of the West Side, long after San Antonio has had its first Mexican American mayor, the repercussions of COPS will still be felt. For the real significance of COPS is not that it has changed streets but that it has changed people—its own people. There are for the first time ordinary folks on the West Side of San Antonio who do not see themselves as strangers in a strange land. Andy Sarabia, Beatrice Gallego, and a thousand others were awed the first time they set foot in city hall; now they are no longer prisoners of the myths and stereotypes that bound them up, and neither are their children.

One family active in COPS lives beside a drainage ditch on the South Side; even a moderate rain threatens their home and leaves water standing in the street. Late one evening this fall a politician and a friend stopped in front of the house to look at the tall grass that clogged the ditch and caused the flooding. The politician was pointing animatedly when a six-year-old boy emerged from the house, walked up to the strangers, and asked, “Are you COPS?”

Five years ago he would have meant something else.

*No, the Yankees.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio