On Sunday, August 28, 2005, Harold Washington was living in New Orleans, supporting himself as a substance abuse counselor and repairing his friends’ computers in his spare time. On Monday, Hurricane Katrina changed all that. The next day, Washington set out from the Ninth Ward, wading through waist-deep water to a house where his wife, their two-year-old son, and her father were staying. They made their way in boats to a bridge, where they were evacuated by Black Hawk helicopter and eventually put on a bus bound for Pineville, Louisiana. Washington had left New Orleans with a pair of shorts, a couple of T-shirts, a cell phone, his wedding band, and an ID. For the next few weeks he and his family bounced around, finally settling in Dallas, where a relative lived. Washington had visited friends in the city seven years before and remembered seeing a lot of want ads for computer repairmen. It seemed like a good place to start over.

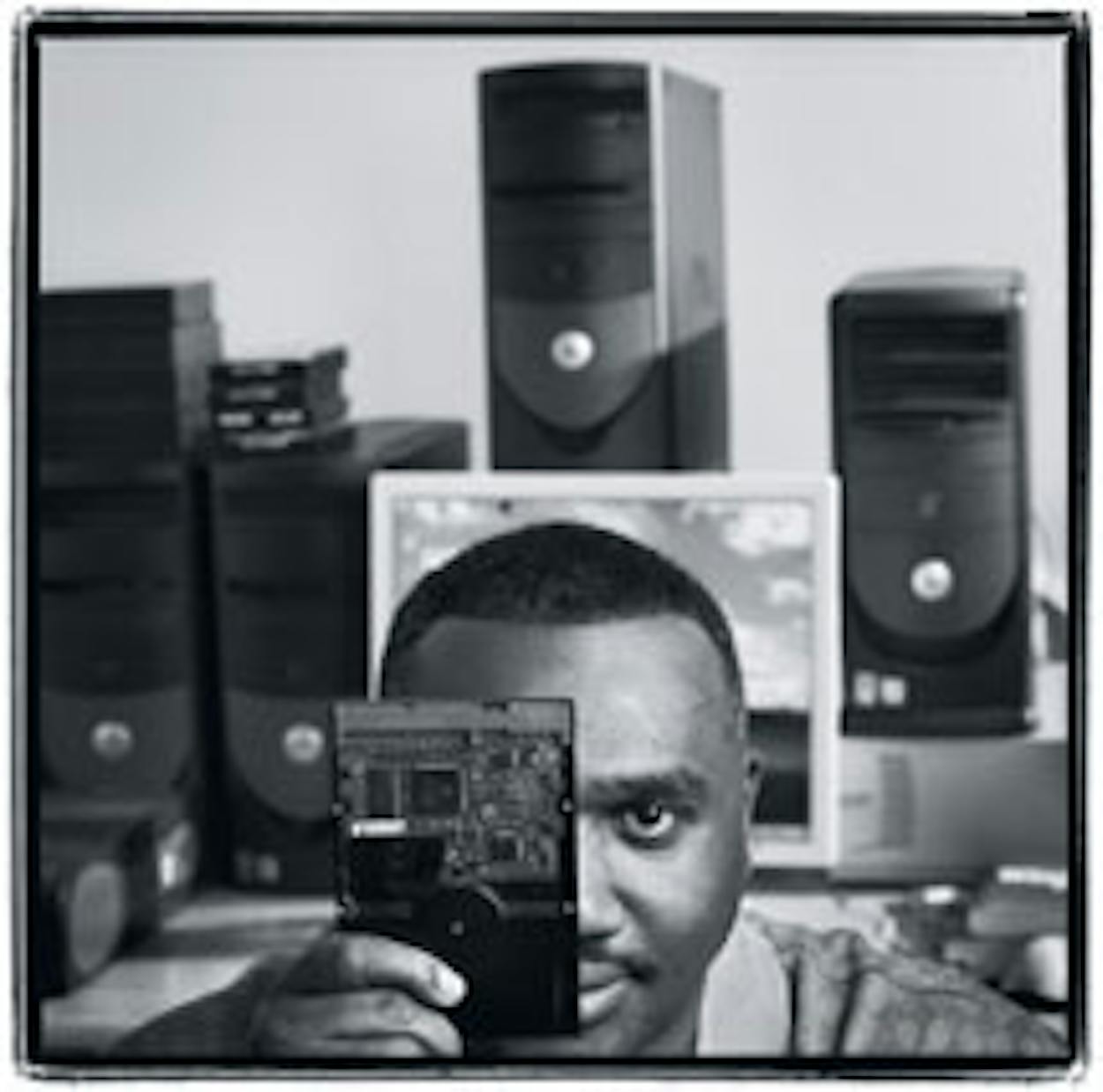

He went to the Texas Workforce Commission, where he was asked what kind of work he wanted to do. Fix computers, he said. The TWC got him a job at a technical school, where he also took classes to get his A+ certification. The woman who hired him ran her own computer-repair-and-sales business and told Washington that, with his experience, he could do it too. Washington was already working on the computers of family and friends, but now he started buying and selling PCs too. In April 2006 he filed papers with the county and made his business official. The name came naturally. “In New Orleans, I called myself King Harold, because it’s my spiritual belief that I’m a king and that my father was a king,” he told me, in his slow Louisiana drawl. “So, King Harold Computer World, where I’m the king of good service.”

In his first year as a small-business owner, Washington, who is 42, made just $5,000. Fortunately, by August 2006, he had left the technical school for a better-paying job at Pitney Bowes, repairing and maintaining mail sorters. On a typical day, he works for Pitney Bowes from eight to four-thirty. Then he comes home and works for King Harold until around ten, though sometimes he’s up in the wee hours of the morning, loading software onto hard drives. The business earns enough to keep him at it but not enough for him to quit his day job.

This past spring, a friend told Washington about a Dallas nonprofit called the PLAN Fund that offers classes and makes small loans to people trying to start businesses without much experience. Since it began, in 1997, the PLAN Fund has made 461 small-business loans. The key word here is “small.” The theory behind the PLAN Fund is known as microcredit: lending tiny but crucial amounts of money to poor people who want to start their own businesses—in essence, teaching them to fish rather than giving them fish. Microcredit, or microfinance, was developed thirty years ago by Muhammad Yunus, a Bangladeshi economics professor who won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize. In the Third World, Yunus’s work with the Grameen Bank, a microcredit lending institution he founded in 1977, has lifted millions from the gutter. In the First World, his theory has been less quick to catch on. Currently, Dallas and Harlem are the only two places in America with Grameen-affiliated microcredit groups. Luckily for Washington, he wound up in one of them.

Washington wasn’t sure if he wanted a loan, but he needed help writing a business plan. Plus, he felt he needed a mentor, someone to help him navigate the obstacles of running a new business in a new city. And so in May he joined seven other hopeful entrepreneurs at the Multi-Ethnic Education and Economic Development (MEED) Center, just east of downtown Dallas, for their first PLAN Fund class. One woman had her own business as a fashion consultant; another had recently launched Epitome, a Christian magazine (“Not gossip, just Gospel”). There was a former math teacher who wanted to start a tax-and-financial-services company and a man who was trying to juggle his three start-ups—a painting studio, an organization that connects African Americans to their heritage, and something to do with distressed houses.

The MEED Center is home to various community organizations and hosts classes in things like English, accounting, and résumé writing; on the other side of the main room, a computer class was just finishing up. A thunderstorm raged outside and the roof leaked a steady drip, feeding a growing stain on the gray carpet. A Coke machine rattled so loud I thought it would explode. The PLAN Fund students sat down around a table, each with a notebook open and a pen or pencil in hand.

Class began with a presentation from Sam Hills, the PLAN Fund’s most successful graduate. In 2003 he launched a medical equipment company that now employs five people and grosses $500,000 annually. “I’m Sam Hills,” he proclaimed, “president and CEO of S&A Oxygen Express, where your needs are expressed!” Hills is regularly called on to give the same stirring speech to incoming students.

“I’ll be the first one to tell you that opening up your own business is not an easy task, but it can be done,” he said, patrolling his five feet of ground at the front of the classroom, left hand in pocket, right hand cutting through the air. “How many of you know where the comptroller’s office is?” Three people raised their hands. “How many of you know where the records office is?” Six responded. “You got to know these things. How many of you talk to someone every day about your business?” A few hands went up. “That’s good, because if you don’t talk to people about your business, how the heck are they gonna know what you do? It doesn’t matter where you are. Go to the movies, talk to the folks. Go to church, talk to the folks. I went to the Black Expo for entrepreneurs in Austin, and this guy walked up to me and said, ‘Hey, you’re that guy. You’re that express guy. You got that oxygen company that does things expressly.’ He couldn’t remember my name, but he remembered that. Get yourself something catchy. And if anybody ever asks what you do, don’t just say, ‘I do basket weaving.’ Say, ‘I do basket weaving! I do the best basket weaving in the town, in the state, in the country! I need to get you a basket right now!’ They gonna remember that. Make your dream come true, because it can.”

When Hills had finished his presentation, the teacher, Adele Foster, asked the students to introduce themselves and talk about the businesses they had or that they wanted to start. “I don’t know how I’m going to get enough money to do all of it,” said the man with three start-ups, “but I’m the ultimate entrepreneur. I am just entrepreneur crazy.” When it was Washington’s turn, he said, “King Harold Computer World, where everyone is treated royally.” The others laughed and applauded. Washington is five feet eleven and muscular, with close-cropped hair and a mustache, both of which are graying slightly. “I’m here because I’ve been talking so much about starting my own business,” he continued, “my friends are sick and tired of hearing me. I work on computers sometimes until ten at night. Sometimes I’m up at two or three in the morning, can’t sleep, go sit at the computer. I have a vision. I want to be known in Dallas as the computer guy. Just call me up and I’ll make sure you get it.”

Before the class was over, Foster laid out some of the topics for the seven weeks of classes to come—marketing, licensing, suppliers, regulations, and insurance. Fixed costs versus variable costs. The Web. Wal-Mart. “I believe everybody can be in business for themselves,” she said. “The info you get with the PLAN Fund you will do something with. There’s gonna be accountability. Class starts at six-fifty. When you walk out, you’ll know what you’re gonna have to do.”

“A middle-class person who wants to start a business goes to family and friends, because those are the people who believe in you. The PLAN Fund is that system for these people.”

I looked around at the students. They were all wearing nice clothes; many, like Washington, had come from day jobs. The PLAN Fund isn’t for the destitute, those who are more concerned with scrounging dinner than maximizing their Web presence. It’s for the working poor. The typical PLAN Fund borrower is a 38-year-old with a household income of $29,700 a year, or 58 percent of the U.S. median household income. But she (three quarters of PLAN Fund students are women) also has poor credit, no bank accounts, and no home equity. “We’re talking about the basics,” Irvin Ashford, a Comerica banker who sits on the board of the PLAN Fund, told me. “No checking account, bad credit; they don’t know how to pay bills; they go to check-cashing places and liquor stores for loans. They’re unbankable. A middle-class person who wants to start a business goes to family and friends, because those are the people who believe in you. The PLAN Fund is that system for these people.”

Microcredit was born in the aftermath of one of the worst natural disasters in the past fifty years. In 1974 Bangladesh had just won independence from Pakistan in a bloody war, only to be slammed with a series of cyclones, floods, and droughts that brought on an unprecedented famine. Historians estimate that more than a million people died. At the time, Muhammad Yunus was teaching economics at Chittagong University, on the Bay of Bengal. Walking to and from the classroom, he passed women and children starving to death in the streets, and the experience pushed him to look outside academia for a real-world solution. He began knocking on doors, talking to the poor.

In 1976 he met a young woman with three children who made bamboo stools for a living. To pay for the bamboo she had to borrow from middlemen who demanded she sell the finished stools back to them as payment; her profit was a mere 2 cents per stool. She couldn’t borrow from the local moneylenders because their rates were exorbitant. She couldn’t go to a bank for a loan because it wouldn’t give loans in such small amounts, especially to someone so poor. As Yunus wrote in his 1997 autobiography, Banker to the Poor, the woman was “a bonded slave.” Her only way out, he figured, was credit. With credit she could buy the bamboo on her own and sell the stools on her own, in the free market.

Yunus decided to try an experiment. He had one of his students put together a list of 42 villagers who drove rickshaws or made things like pottery and mats; then he loaned these people small amounts to buy their own raw materials and sell their products at their own rates (the total Yunus initially gave out was less than $27). Next he went to a bank and borrowed $300 to make more loans. To his surprise, almost all the people repaid the money. In 1977 he founded an experimental branch of a local bank to make these “microloans.” It was called Grameen, from the Bengali word for “village.” No collateral was needed. Yunus made borrowers work in groups of at least five—for support among members but also to take communal responsibility for the loan. He sought out women, both because it was almost impossible for them to get loans in a Muslim society like Bangladesh and because in his experience, women were more responsible than men and more likely to use their extra income to support their families. Many of the Grameen loans were only $25, a lot of money in rural Bangladesh. Interest rates were high, up to 20 percent, but not nearly as high as those of the local Tony Soprano.

Grameen was so successful (in some years the repayment rate was 98 percent) that soon international development banks were loaning it millions of dollars to work with. In the eighties, Grameen added branches throughout Bangladesh. At each one the story was the same: Without much in the way of collateral or training, a person could come in and get a small loan to buy a milk cow, fix a cart, or sell some rice on the street.

Yunus’s philosophy was based on his faith in the free marketplace. “I believe in the central thesis of capitalism,” he wrote in Banker to the Poor. “The economic system must be competitive . . . an entrepreneur is not an especially gifted person. I rather take the reverse view. I believe all human beings are potential entrepreneurs.” Gradually, Yunus became something of a celebrity. He traveled the world, preaching the gospel of microcredit to enraptured crowds and winning over converts like Kofi Annan, Bill Clinton, and Bono. In 1997, with Yunus’s blessing, an offshoot of Grameen was launched to give small loans in Latin America, Africa, and the United States, where most banks won’t consider making business loans of less than $10,000. Yunus asked Alex Counts, an American he had worked with in Bangladesh, to run the nonprofit, which was called the Grameen Foundation-USA (later simply the Grameen Foundation). When Yunus came to Dallas to give a speech promoting the new venture, a local social worker named Gwen Moore was in the audience with her husband.

“I wasn’t expecting to be so inspired that night,” Moore recalled. “My husband and I, we said, ‘We’ll never meet another person like that in our lives.’ We thought we’d met Gandhi. One thing he said that night was ‘It only takes one’—to make a difference. I gave notice at my job that week.”

With Regina Nobles, who worked for Dallas City Homes, a low-income housing developer, Moore started an experimental Grameen-inspired loan program. They’d made thirty loans when, in October 1998, they invited Counts to come and see their operation. The Grameen Foundation was already working with one American group, Project Enterprise, in Harlem, and Counts and Yunus liked what they saw in Dallas. “Dr. Yunus urged us to get involved,” Counts told me. “Our basic approach was to apply and adapt the Grameen approach to the troubled neighborhoods of Dallas.”

Almost three fifths of Dallas was in the low-to-moderate income range, and Moore, Nobles, and Counts were determined to change that. “We really wanted to help a lot of people,” Moore told me. “Our original business model called for helping two thousand people in five years.” They called the new organization the PLAN Fund. Like Grameen, it used the peer group model as much as possible (PLAN stands for Peer Lending Action Network). Borrowers went through a ten-hour “certification process” in basic business ideas, then they got loans, an average of $1,000 each. “We didn’t want the PLAN Fund to be cautious,” Counts told me. “We had an aggressive, proactive model. We went out with live bullets. We asked them to take risks.”

They did, making loans to 351 people in those first few years, sometimes without a credit check, indeed without a lot of rules or restrictions. The results, it became clear, were not worthy of any Nobel Peace Prizes. “The word on the street,” said Moore, who is now the president of the PLAN Fund’s board of directors, “was that we were easy money.” Moore and Nobles’s good intentions had gotten in the way of good business sense. The people getting chunks of money weren’t asked to give much in return, and many didn’t; their businesses never took hold, and few borrowers paid back their loans. The default rate eventually soared to 40 percent. “We wanted to work with people, help them succeed,” Moore explained. “So when they weren’t paying on their loans, we let them slide.” Though many businesses did succeed, including S&A Oxygen Express, the leaders of the PLAN Fund realized they had to reevaluate the fundamentals of microcredit. “We dreamed too big,” Moore said. “You come in with naiveté: ‘We can fix anything.’ You learn it’s not so easy.”

The problem was that the Grameen model had not been developed with the First World in mind. In Bangladesh, as in most desperately poor Third World countries, a majority of people make their livings, such as they are, through some kind of entrepreneurship—

selling pencils on a street corner or taking in laundry to wash. The alternative is starvation. By contrast, maybe one in twelve Americans runs his own small business. Our sophisticated, super-regulated economy makes it hard to work for yourself and offers plenty of jobs working for someone else. It also offers plenty of buffers to starvation: the minimum wage, food stamps, or at the very least a daily lunch at the Salvation Army. Another big difference: In Bangladesh the peer groups have a genuine social cohesion; a loan would go to a group of women who often shared in the basics of daily life, such as getting water from the same well. In Dallas, borrowers in a group were usually strangers who were scattered around the city.

These inherent differences between the Third and First worlds have led some economists to question the promise of microcredit in America. One 2001 study argued that “in the first world, microenterprise is not a panacea but a vitamin.” It went on to conclude that “most of the poor will reach the middle class through education and wage jobs.”

“The Grameen model works well in Third World nations where there’s a communal aspect,” Ashford, the Comerica banker, explained. “In Texas, we believe in our own fortitude. We live by a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps mentality.” In 2004 the organization retooled itself, becoming an independent nonprofit, though still with ties to Grameen. Anthony Pace, who was hired a year later to be the new executive director, told me, “In the first years, the program’s emphasis was on loans: Get ’em in, get ’em out. You may be able to do that in Bangladesh but not in Dallas.” Pace, a boyish, fast-talking New Yorker with a background in international business, worked with Counts to create a hybrid—taking the best of microfinance over there and mixing it with the best of capitalism over here. “There were no books on how to do it. We had to experiment on how to make it work in Dallas.”

They upped the training considerably, to a two-and-a-half-month-long program of classes (to better educate but also to weed out the unmotivated), and they strengthened the group support idea. “In Dallas, you need more than loans,” Pace told me. “Microfinance is about breaking psychological barriers, about starting a business and saving money. You gotta change psyches.”

A couple weeks after the first PLAN Fund class, I went to visit Harold Washington at his home office and see how things were going. Washington lives in a third-floor apartment in a mile-long block of identical apartment buildings in Carrollton, a suburb north of Dallas. (He and his wife are now separated.) His living room was crammed with cardboard computer boxes. An ironing board held stacks of recordable CDs, and the floor was full of monitors and mouses. In the small dining room, a table was piled high with another monitor and two towers, both loaded with software. Five more towers sat underneath it. A Dell computer box served as another table, this one strewn with more CD-Rs and cables. A couple of older computers had been opened up on the floor for parts. A copy of a book titled The Greatest Salesman in the World lay on the kitchen counter. “It’s by Og Mandino,” Washington told me. “He says, ‘Don’t run your business just on making money—use your heart.’ That’s my blueprint.”

He was making most of his money through sales. “My thing now is having the money to purchase Dell computers,” he said. “Once I sell $25,000 worth of Dells, I get a big wholesale discount. I want to be able to offer brand-new Dells for $599. Wal-Mart sells them for $848.” Eventually, he thought he’d make his real money on service calls, and he said that that side of his business was starting to pick up. “Every Saturday I have somebody’s computer to fix. Geek Squad charges $159 to just show up. I charge $65 an hour. Things were slow the first three or four months. Since then, the phone hasn’t stopped ringing.”

Washington had been trying to get a couple of contracts—with the Dallas Independent School District and the Minority-and-Women-Owned Business Enterprises at DFW International Airport—and he thought the PLAN Fund might be able to help him get his proposals together. Though at first he hadn’t been sure if he was going to apply for a loan, he now thought he would. He could use the money to buy more equipment, more Dells. Plus, a successful loan would help raise his credit rating. His goal was to be running King Harold Computer World full-time by the end of the summer. “After I get a business plan,” he said, “I can go to the Small Business Association, get a $10,000 loan from Chase or Capital One, get a storefront. All I need is a storefront.”

The PLAN Fund is by no means the only microcredit group working in the U.S. There are around five hundred American organizations that help people start small businesses, and like the PLAN Fund, most offer not only loans but training as well. What makes the PLAN Fund different is its commitment to and affiliation with the Grameen model: The loans it makes are really small, and it emphasizes the peer group—lending approach. (Project Enterprise, in Harlem, is still the only other Grameen group in the U.S.) Students, who pay $25 for materials and a $50 annual membership fee, take eight weeks of Business 101 classes with the same people. After that, they form peer groups of four to eight people and begin going to biweekly “center meetings,” where they hear lectures and get one-on-one help from teachers. It’s like a country club for the working class, a place where members make contacts, network, gossip, and trade ideas.

“A lot of these people are in environments hostile to starting a small business,” Counts told me. “There are temptations to spend money on get-rich-quick ideas, or people are trying to borrow money from them. It’s hard to stay positive. In the early days of the PLAN Fund, there was a woman who bought a used car to do her catering business, and her boyfriend was so threatened by her success that he put sugar in her gas tank. The peer group helps people stay around others who are seriously working on their business, who can give them a pep talk.”

Some of the classes and peer group center meetings I attended had the feel of new-age encounter sessions. For her class on how to write an executive summary, Adele Foster spread a bunch of things on the floor—a shoe, a small purse, a scarf, a bottle of water, some Post-its. “An executive summary should summarize what your business is about,” she told the students, inviting them to pick up an object and explain what it represented about their business. “This is for watering my business with new ideas and customer service,” said one young woman, waving the water bottle.

Other classes were more conventional. One week I watched Cornelius “Neil” Small teach nine women and four men at the Parks at Wynne-wood, a public housing facility in Oak Cliff. The lesson was “My Projected Sales Revenue.” Small, a former loan officer and counseling coordinator with the Small Business Development Center, talked about cash flow, figuring out market share, and scoping out the competition. “Identify your competition,” he said. “There’s nothing more annoying to me than someone telling me there’s no competition. I’m here to tell you, if there’s a product or service out there and it doesn’t have competition, you don’t want to be selling it. Know your competition. How are you going to be different? You gotta be cheaper, better, or faster, okay?”

After two of these peer group meetings, you can apply to the loan committee (made up of community members and PLAN Fund board members), and if you’ve made it through the classes, meetings, and the application process, it’s extremely likely you’ll be approved. First-time borrowers can ask for $500 to $1,500; second loans are for $750 to $2,500; the third loan, called the “transitional loan,” ranges from $2,000 to $4,000. Hopefully, the fourth loan will come from a bank. PLAN Fund loans carry an interest rate of 9 to 12 percent, which Pace told me goes back into the loan fund.

During the early, freewheeling years before Pace became director, the PLAN Fund made 438 loans for $630,525; since then it has made just 23, for a total of $44,459. The main reason for the lower numbers: the more rigorous training. A lot of people don’t make it. “Life just happens,” Small told me. “Some will drop out, think, ‘This is something I don’t want to do.’ Others won’t have any choice. Transportation is really an important issue for a lot of these people. They don’t have decent cars to make it to class every week.”

Two who have made it, who have each taken three PLAN Fund loans and who regularly come to biweekly center meetings, are Julieta Hernandez and Veronica Rivera. Hernandez grew up in Ciudad Acuña, across the border from Del Rio. Her parents ran a small store selling clothing and novelties. She married and had four children, and in 1999 the family moved to Dallas. Her husband toiled at two maintenance jobs while she worked as a cashier at a drugstore, though she dreamed of having her own store. She loved to sell, but what could she offer that people couldn’t get at Wal-Mart or Target? She recalled the comforters, or cobertores, that everyone used on their beds back home. With so many Mexicans now living in the Dallas area, surely there would be a market for these blankets. In 2002 she started selling cobertores and called her business Galería Internacional. The following year, she heard about the PLAN Fund and began coming to classes.

After several months of center meetings, Hernandez was approved for a $1,500 loan. She bought seventy comforter sets and sold them through word of mouth. “My customers would tell me, ‘Go to my mother’s house—she’ll buy a couple.’ I tell people, ‘If you need something else—boots, underwear—I have that too.’” She took out another loan, bought more comforters, sold them. Last year, she took out her third loan, for $4,000, and by the end of the year she had cleared $10,000. Her husband was able to quit one of his jobs. At one of the center meetings she discussed how, with gas prices so high, she would probably be better off selling in one place. After her next loan, she’s going to the Small Business Association and then a bank—“Leave the PLAN Fund, become independent. My credit is much better now.” I asked if she was looking for a location for a store. “All the time. I’m dreaming. It’s soon.”

Rivera is from Mexico City. She went to her first PLAN Fund class in 2000 and one year later started a janitorial company, J.B.S. Cleaning Services, with her husband. The initial loan enabled her to buy a used car, and the second one five vacuum cleaners; with the third loan she bought some steam-cleaning equipment and a better car, which she uses to pick up some of the ten people she and her husband employ. The company cleans businesses and homes all over Dallas. The PLAN Fund helped her get her business plan together, but mostly she credits the support system. “My group is five people. The others in the group would say, ‘You can do better—come on! Don’t quit!’ That’s important, because sometimes we feel we can’t do it. If I have a problem with my business, I can call Anthony Pace. He gives me numbers. I didn’t know anything about sales tax permits. They have someone at the PLAN Fund who talks specifically about the sales tax.”

Last year J.B.S. grossed $60,000; this year Rivera expects to make close to $100,000. “I love this country,” she told me. “This is the country of the opportunities.”

Hernandez and Rivera have succeeded because they did the hardest thing of all: They stuck with the program. “Basically,” Small told me, “business is about trying. If you keep trying, you’ll succeed. Staying with it—that’s what the support of the group is all about.” I told him about the look I’d seen in Hernandez’s eyes when she talked about her plans for Galería Internacional. He nodded. “That’s the tiger’s eye—it’s palpable. I can look at someone and tell if they’ve got it. But I find fewer people in the low-to-moderate income range have that look in their eye. Folks have so many issues to deal with, they don’t even think about starting a business.”

Almost everyone who had come to the first class showed up at the last, on June 27, even though it was raining so hard people were getting washed off the streets of Dallas. The students took a written test, and Pace and Foster discussed the answers afterward. “Provide four examples of marketing tactics that can positively impact a sales forecast,” read Pace. “Business cards,” said a young man. “Word of mouth,” said a woman. Foster talked about a restaurant that had dressed someone up in a costume and put him by the side of the road: “What can you do that’s outrageous to make you stand out?” Harold Washington answered, “How about calling yourself a king?” and everyone laughed.

Pace asked how many were expecting to apply for loans. Four raised their hands, including Washington. Pace said the PLAN Fund would work with anyone who was having trouble repaying a loan. “Since I’ve been director, we haven’t used a collection agency,” he assured the students. Foster called out names, and Pace gave certificates saying they were now PLAN Fund members. When she got to Washington, he said, “Roll out the red carpet!”

After class, he told me that the best lesson he’d learned over the previous two months was cash flow. “I didn’t know nothing about cash flow. But to run my business, I need three things: an operational fund, a tax account, and a payroll account. I need to put seventy percent in the first, twenty percent in the second, and ten percent in payroll, which is for me. I never thought about that, setting aside money to pay myself. My group leader told me that.” His peer group had helped him write his executive summary. He was also fixing one of the women’s computers, while the former math teacher was doing his taxes.

By June, Washington had talked with a man at the DISD who gave him the number of a woman in the purchasing department; he left a message with her. “She didn’t call back,” said Washington, “but I talked with him. I made a contact.” He had also talked with a man at the Minority-and-Women-Owned Business Enterprises at DFW. “He said I can work with the airport and directly with their subcontractors. He said he’d e-mail me all the info to talk to the purchasing person at the airport.” Though neither action had led to any business, Washington seemed confident. “I’m making personal contacts. I have somebody I talked to. I’m building myself up in the computer community.” He was still looking to get the Dell deal, and he was still planning on applying for the loan. “I want to buy equipment. I need it to keep a positive cash flow.”

But when I caught up with him a month later, he wasn’t so sanguine. “Right now, I can’t afford to get the loan,” he said. “I don’t want to chew off too much. The loan process is a long process. My group has to look at everything. They have to say if I’m ready.” Business was slow; he’d sold two computers that month, with another sale pending, but it was summer. “I’m waiting to see if everything will pick up next month when school starts. Hopefully my phone will ring more. If I can get the sales, I can get the loan to buy the equipment. I don’t want to get the loan and not be able to buy equipment with it. Our group leader told us we shouldn’t buy anything we’ll have in inventory for forty-five days or more. That money should be in the operations budget.” For the first time, Washington seemed depressed. His FEMA rental assistance was about to end, plus he had not met his goal of running his business full-time by August. He’d made it to the first center meeting but not the second, in early August, at which he would have had to announce whether he was applying for a loan. It was the first PLAN Fund meeting Washington had missed.

Two weeks after that, he was amiable King Harold again. His latest plan, he told me, was to open an eBay account and sell computers online as a way of getting to that $25,000 mark. “If the eBay thing takes off, I should have the Dell deal by December.” He said he saw Dell towers for sale on eBay for $500. “I’ll do the tower and a flat-screen monitor for $499.” So he was open to the loan again. “When people e-mail me and say, ‘I need a computer,’ I need to have it ready to go. With $1,500, I can buy four computers.” He held out hope for the DISD deal, though he still hadn’t heard from the woman in the purchasing department.

What had changed since early August, I asked. It was the group, he said. After he missed the second center meeting, members had started calling. “Everyone in my group called me—‘Heard you been having a hard time. What’s going on?’ They came to my rescue. They told me, ‘It’s gonna be okay. Business is gonna pick up.’” Then he got an extension on his FEMA aid to November. He planned to keep coming to the center meetings for the support. “I’m optimistic right now,” he said.

I asked Pace what he thought about Washington’s chances. “It’s hard to tell. It’s tough to succeed in business, especially with a couple of strikes against you. If you have more income and more savings, you can afford more risk. I always say to borrowers: Keep your day job, do it on the side, get experience and confidence, then go full-time. Sam, Veronica, Julieta are all people who have been with us for years. Harold has only been with us since May. At the low-income level, the margins for failure are so small—it takes less to knock someone down or out.”

The skeptical economists are probably right when they say that, for the most part, the poor in America would be better off getting an education or working for someone else. For the most part. Economics is a logical science and doesn’t—can’t—take account of the tiger’s eye, to say nothing of those who are just entrepreneur crazy. The poor will be with us always, but so will those who can’t sleep at night for thinking about their computers, their comforters, their American dreams.