This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Best way to understand this place,” beat patrolman R. C. Nettles says of the War Zone, “is this: almost no one is here for a good reason. You got criminals and victims, pushers and users, and some folks caught in between. And us.”

Nettles, tall, rangy, and good-natured, and his partner Jim Reynolds, stocky and graying, are working the day shift on a torturously hot Wednesday in July. As always, they cruise the streets of the South Dallas ghetto in search of some crease, some tiny seam in the facade of the burned-out neighborhood through which they can master its internal order. The grim face of poverty assaults the senses: endless rows of largely abandoned and neglected tenements, shotgun shacks, teenage mothers tending to their impossibly large broods, and vacant-eyed young men strolling the streets with that particular ghetto gait—no place to go.

Reynolds swings the patrol car southwestward on Grand Avenue and heads for the Wayside. The Wayside is the Wayside Inn, though it is doubtful the place has seen much conventional traffic in recent years. But, according to Nettles, it has seen just about every other kind—prostitution, drugs, pornography. The Wayside is close to being the War Zone’s pulse center, and Nettles has made frequent drug arrests there.

The officers check the parking lot for suspicious-looking cars and jot down a few license numbers, particularly those of rental cars, which almost certainly means a drug deal in progress nearby. Then Reynolds pulls the squad car up to a young black woman who is sleeping on the stoop of one of the rooms. He gives his siren a quick jolt. The woman rouses unsteadily and saunters toward the car. She is dressed in a soiled orange blouse, slacks, and sandals. She says her name is Stephanie.

“Can’t sleep in public,” says Nettles. “Against the law. Why don’t you go home and sleep?”

As Nettles continues his lecture, a vacant, slightly loony gaze crosses her face, a look that is the universal badge of the crack addict. “Candy face,” it is sometimes called in doper circles, and it is every bit as much a part of the topography of the War Zone as the drab, hopeless architecture of the slum apartments.

As we drive off, Stephanie returns to her perch, oblivious to Nettles’ admonitions. “You tell them to stay away,” he says, tired already. “But where can they go?”

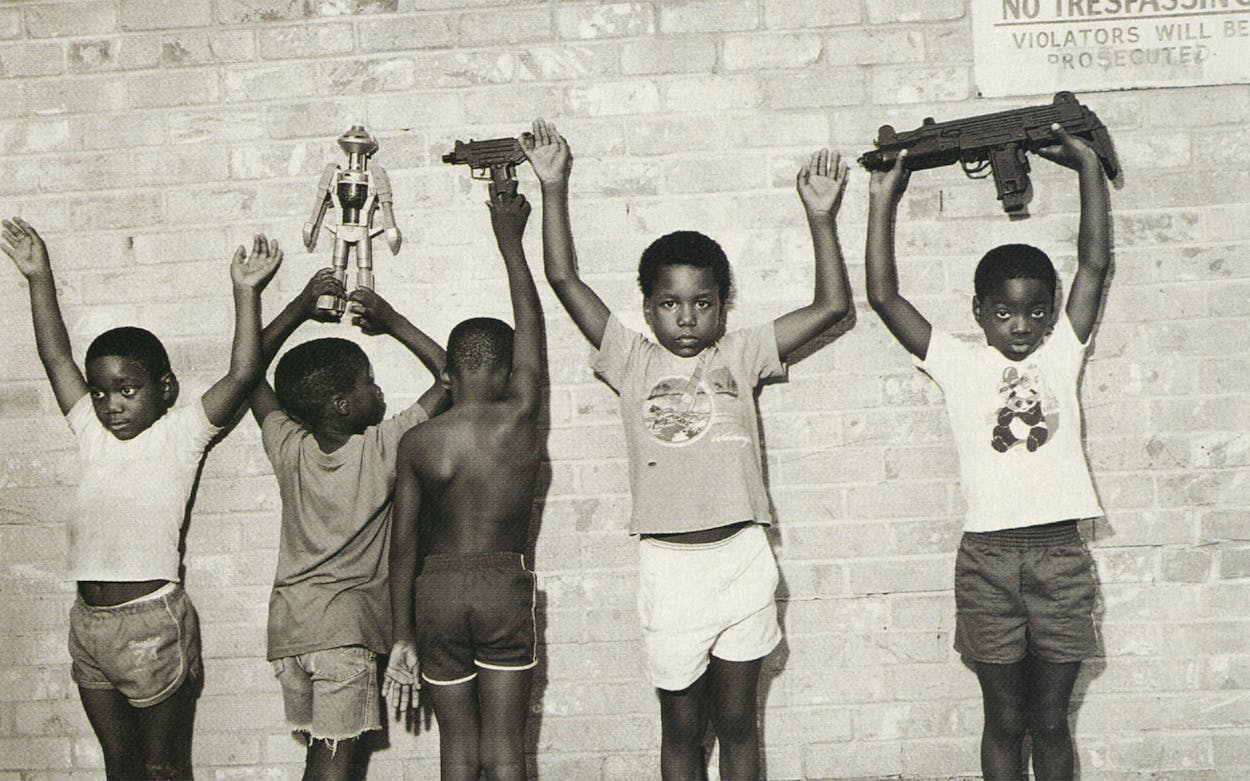

As the morning wears on, the streets unlimber a bit. Kids play in dusty, treeless apartment courtyards; teenage boys languish in the dozens of empty, weed-infested lots in the neighborhood. In time, other teenage boys, those better dressed, appear on street corners and apartment stoops. Many of them are members of the War Zone drug trade’s lowest echelon—small-time street dealers, or “good eyes”—lookouts for the proprietors of the neighborhood’s larger crack houses. An industrious good eyes can make $50 to $100 a day, which has made the job a coveted one in the War Zone.

The officers pull over one young man after they spot him taking a hasty left in the area of several known crack houses. He responds to their warnings to stay away with a halfhearted candy-faced glare. On Jeffries Street we encounter two more candy faces, one a middle-aged black man who wants Nettles to check his driver’s license on the computer to see if he is straight with the parole board, the other a teenager who stares at the squad car briefly before quickly disappearing into the bramble.

Men, women; young, old. In the swatch of Dallas that runs south from Interstate 30 to the Trinity River bottoms along either side of South Central Expressway, the candy face is everywhere. It’s easy to conclude that this is not merely a poor neighborhood invaded by drugs. It is occupied territory, a neighborhood claimed by crack. Drugs aren’t a subculture here. They are the culture.

As we prepare to head off to lunch, Reynolds takes one more swing westward, where we encounter a familiar figure. On the steps of a one-story office building lies a young black woman. As the patrol car guns past her, she raises her head slightly and gives us a candy-faced stare. It is Stephanie.

It is conventional wisdom that despite the good intentions and spending programs directed at poor inner-city neighborhoods since the sixties, most of them have, if anything, deteriorated in the last 25 years. And since 1983 neighborhoods like the War Zone seem to have gone from worse to worst. The area hasn’t always been a ghetto, and it certainly hasn’t always been a war zone. In the earlier part of the century, in fact, Forest Avenue, Park Row, and many of the other streets here were lined with the mansions of Dallas’ gentry. Even into the fifties the neighborhood served as a haven for wealthy Jewish families. One can still spot the crumbling shadow of a once-fine home crammed in and among the cracker-box apartment houses that shelter most of the neighborhood’s present population.

Like many inner-city neighborhoods, the War Zone lost its wealthier inhabitants to the suburbs; working-class blacks and whites settled in South Dallas in the sixties as they moved to the city from small towns and rural areas in search of work. The architecture changed to suit those new inhabitants as cheaper apartment complexes replaced single-family homes. Like many poor inner-city communities, the neighborhood always had more crime and drugs and despair than other parts of town did, but as ghettos go, it was always known as a relatively quiet, well-kept neighborhood of working-class poor. Some—but never all—of the people got high, and their choice of intoxicants was limited to comparatively harmless substances like marijuana, uppers, and cheap wine.

In the mid-eighties events conspired to change the neighborhood. They happened so fast and so fiercely that the place seemed to change overnight. First, a new drug hit the streets, a purified form of rock cocaine called crack that was at once the cheapest and the most potent narcotic ever to make its way into the hands of a junkie. As late as September 1985 the drug did not figure into calls made to the national 800-COCAINE hotline; nine months later one third of the calls referred to the drug. Crack seldom appeared outside New York City and Los Angeles until late 1985 or early 1986, but within the year no less than 25 states were reporting significant usage of the drug.

With the new drug came a new kind of dealer. Gone was the neighborhood pusher who dispensed from his home and, like his customers, was known to residents and police. In his place came Cuban and Jamaican families and groups who introduced a more organized and decidedly more vicious style. The invaders used terrorism to run off local dealers and take over the neighborhood. Law-abiding citizens took refuge in their homes; local teenagers, whose job prospects were slim, were recruited and then punished savagely if they didn’t peform up to standard.

But the siege wasn’t complete until the Dallas economy busted, sending the neighborhood even more deeply into despair. When day laborers, who had filled so many of the apartments, were laid off, they moved on, leaving an almost perfect physical and social milieu for crime: rows of apartments with hidden U-shaped courtyards and alley access, where dealers could move in and operate invisibly. There are no fences between the units; vacant lots overgrown with four-foot weeds and filled with piles of rubble provide additional hiding places.

The local population consisted almost entirely of either those who wanted a piece of the action or those who were more than willing to turn their backs on it. This area ranks near the bottom in statewide median household income; its unemployment-to-population ratio is among the highest in the city, as is its percentage of residents below the poverty line. Its purchasing-potential index ranked in the zero percentile in 1987. Only 4 percent of its residents have college degrees, and more than 50 percent of the residents are under 34 years of age—suggesting that the process of going from worse to worst isn’t going away anytime soon. The neighborhood is hopelessly transient, irrevocably unstable; nearly 70 percent of the residents here are renters, nearly 50 percent of the housing units contain three or more apartments. Moreover there is a profound absence of traditional nuclear families. As in wartime, women and children predominate. The men one sees are the elderly and the infirm or the young toughs.

The neighborhood looks easy to roll over, and it is. Since 1984 crime in the area has risen 30 percent; on one beat in the War Zone violent crime runs thirty times the citywide average. Gunshots pepper the air day and night; many people are armed, and few if any residents believe the police can solve the problem.

The extent of this neighborhood’s surrender to another authority became clearest earlier this year, when Dallas County probation officers, after suffering endless threats and intimidation during their monthly trips to see probationers in the area, announced that they weren’t going to enter the War Zone anymore unless they could be armed. Dallas police officers followed suit by begging their superiors for automatic weaponry equal to that wielded by drug dealers. Maybe we have long had neighborhoods where middle-class folk don’t like to go. But the War Zone has become a place where even cops don’t like to go.

The crack house in question wasn’t a house at all but an upstairs apartment at the far end of a withering, dusty complex on Clarence Street. Nettles had heard via the grapevine that a group of Jamaicans had been dealing there the previous week. But with the number of abandoned apartments in the neighborhood and the almost feline way in which the dealers move from one building to another and back again undetected, Nettles wanted to see if the Jamaicans had already evacuated.

A pair of shirtless young black men loitered on the steps, eyeing the patrol car with that singular look that folks in a neighborhood like this seem to have been born with: a combination of wariness, contempt, and a strange practiced indifference. The taller one stood and began shouting, “Police! What you all doing here? Police!”

As we were about to climb the stairs to the balcony, Nettles turned to me and advised, “Last I heard, one of these guys has an Uzi, so you know, if you see something move in the doorway, don’t be ashamed at all at just pitching yourself over the edge here.” This was the third day I had been with Nettles, and I was by now used to his good-natured sarcasm about his work. But I could tell he wasn’t kidding this time.

Those stories of twenty-year veteran police officers who retire without ever having drawn their guns may still be true in some neighborhoods, but officers who work the War Zone must operate on the premise that it is not merely a possibility that they will confront gunplay, it is a likelihood. During the time I spent with Nettles and his partner, they drew their pistols at least once a day, searching crack houses.

The apartment is clear at least for now. As is often the case, the Jamaican dealers have left behind remnants of their trade: spoons used in processing the crack, small plastic bags used to package it. The soiled carpet features an assembly of abandoned personal effects, such as clothing and makeup, some fast-food containers, a few laundry hangers, and a fedora. The dealers have torn a hole in the wall shared by the adjoining apartment, which apparently was also rented by the dealers—a means of ready escape frequently employed by Jamaicans in the event of a bust.

But they are long gone, off to any one of dozens of other abandoned apartment buildings or perhaps simply to return here another day or another night. “They’ve only been here a couple of years,” says Nettles as we walk back down the balcony, “but they know this neighborhood like they grew up here. And they know where we are almost better than we do.”

A black youth stops Nettles and his partner that day, John McGuire, at the top of the steps and motions them toward his apartment door. He points to a gaping hole in his front window and then to a shattered mirror just inside the front door. “They did that,” he says. “Just the other night. I don’t know why.”

“Did you call the police?”

The man shrugs and gives the answer the officers are well accustomed to: “No.”

Walking back to the patrol car, I ask Nettles if he thinks the kid was involved in the drug trade and was the subject of some kind of retaliation. “Could be,” he says. “On the other hand, with these Jamaicans, sometimes they just go to shooting up a place as a means of enforcement, to let these folks know who’s in charge. That’s the thing about them. They’ll just shoot you for the hell of it.”

The Jamaicans first appeared in the War Zone in 1986, fast on the heels of Cuban dealers, who had set up shop in Dallas and various Midwestern cities about a year before. The invasion was remarkably well orchestrated. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Jamaicans operating in these cities are part of a network based in Brooklyn. They were dispatched to the hinterlands because the turf in the Northeast had long since been established and the market had hardened. Places like Dallas were wide open, and because of the relative shortage of crack in the area, the Jamaicans figured, they could charge a higher price at less risk. They were well-trained, well-armed, and well-financed drug soldiers, not crooks or thugs or toughs—but warriors.

If the Jamaicans represented a more vicious sort of drug dealer, they were also a more clever one. Their distribution system is remarkably simple and streamlined. A bulk of the drug is generally flown in from Miami, Houston, or Los Angeles and picked up by a courier, who meets a dealer at a predetermined drop-off point. The dealer sells it himself or distributes it to lesser dealers at smaller crack houses. In either event, the object is to move all of the drug in as short a time as possible, thereby eliminating evidence. Within the next day or two the cycle is repeated, often at an entirely new set of locations with perhaps an entirely new set of dealers. One other reason that crack can seize a neighborhood is that it is remarkably profitable. By cutting the drug with cheap cocaine substitutes during the cooking process, a crack dealer can turn a 150 percent profit on the raw product. Still, the drug is always easy for users to find. Stroll down any of the War Zone’s major thoroughfares—Grand, Oakland—and practically anyone on the street can tell you where the dealers are doing business that day.

It is organized chaos of a kind that has stumped drug law enforcement. Before crack, the dealer and his point of sale could be pinned down with enough legwork. The odds were good that a few days later, if a cop served a warrant on a dope house, evidence and probably a suspect could be found. The Jamaicans changed that. They are everywhere, anywhere, in a place like the War Zone.

The Jamaicans have cash, which in hard-pressed South Dallas is the great seducer for everyone from apartment managers to unemployed teenagers. With the recession, occupancy rates in the neighborhood run as low as 50 percent. Typically, Jamaicans will infiltrate an apartment house by sending in a well-dressed woman—usually with a child and the deposit and first month’s rent in hand—to do the leasing. Maybe she’ll rent a second apartment for a friend. Then most likely the landlord will never see her again; sooner or later she’ll be replaced by dealers.

Perhaps more insidious is the way in which the dealers have managed to infiltrate the teenage populace of the neighborhood. In the early days of the invasion, the Jamaicans themselves ran the crack houses. But with hard times exacerbating already high unemployment rates among teenage youths, the dealers found a compliant and eager young work force among neighborhood kids—now they do the Jamaicans’ dirty work. Indeed, the only noticeable daytime presence of the Jamaicans is the occasional anomalous sight of a Cadillac or a Mercedes parked on a side street.

The kids are recruited through mutual acquaintances or sometimes right off the street. The first stage of the courtship involves the dealer giving the kid some money or even buying him a car, and telling him to go have a good time for a while but to be available when needed. When an operation wants to expand or, more frequently, a young dealer slips into debt, the big dealer already has a loyal apprentice on the payroll.

Part two of the courtship is a little less pleasant. Through intimidation and physical threats, the young dealer is kept in line. A transgression as simple as coming up $5 short on collections can earn the kid a beating or, worse, a wound to the foot with a .357 Magnum. Further transgressions will leave him shot in the head. A horrifyingly common sight in the War Zone is a youth limping around on crutches after having been shot through the foot as punishment for crossing his dealers.

One young man that Nettles ran across one afternoon had been shot in the foot and neglected to go to the hospital. His foot was the size of a basketball and had turned an ugly gray. When Nettles asked him why he hadn’t been to the doctor, he responded with a candy-faced shrug.

“I‘m going to another funeral tomorrow,” says Robert Hall, reciting a lament that has become fairly common in his life during the past few years. Hall has lived in the War Zone for fifteen years and manages an apartment house there. Like most of the other residents who have tried to resist the Jamaican occupation, he is still shocked at what has happened to his neighborhood.

“Like last night,” he says, gesturing up Jeffries. “Right there, they tried to shoot up this little girl. That’s been the latest thing. They’re using young girls now. Say they can trust them more.”

Hall sports a roughly cut Afro and wears a stylishly torn T-shirt and jeans. By his own admission, he feels like an outsider in his neighborhood: “Yeah, I hear it all the time when I’m walking around at night. There goes the cop lover. There goes the snitch. I guess probably some of my old friends even think that.”

By his count, Hall has lost twenty old acquaintances to drug-related violence in recent years. “I lose them to the violence, or I lose them to the drug,” he says. “I have a friend I saw recently who used to be a truck driver. Owned his own truck. He’s blown it all on crack.”

Some friends who have gone to work in the drug trade have tried to recruit him. “Oh, yeah,” Hall says. “They come around with money and the cars, and they say, ‘You’re a manager. You’d be good at this.’ It’s a money thing. You take a sixteen-year-old down here and give him a car, and it will get his attention. I see my friends sometimes and I see they have nicer clothes and I know what’s going on. But man, I see other ones, I see them smoke the crack and walk to get some more. Smoke and walk. That’s all they do. Once they own you, you are theirs. Little sixteen-year-girl I knew got shot up the other night because she wanted out.”

We are joined at his office by Margie Walker, another apartment manager who has lived in the neighborhood since 1962. She says, “I was walking into the grocery store the other day, and this little nine-year-old comes up and says, ‘You want some crack?’ I knew the little boy. We always had drugs here, but this is something else. This has taken over.”

She watched in horror a few months ago as a girlfriend who had become ensnared in the crack trade was beaten and stabbed to death in an apartment house across the street from hers. “It was over and they were gone before I could even get my breath,” Walker says. “But people are getting used to it. That’s sad. There’s no pride. They see trash littering these lots—they ignore it. They hear gunshots—they ignore it.”

Hall remembers when he realized something very bad was going on in his neighborhood. He was managing a different apartment house in the area, and one day he heard shots ring out in the complex. Rushing out of his apartment, he realized they had come from the direction of an apartment where two of his friends lived. He found one sprawled on the floor, a bullet through the head. The other was literally blown up against one wall. “I thought, ‘Gee, I never thought this place could get any worse.’ But it did,” he says. “We’ve lost it. They’re going to use us up and then leave us behind for dead.”

On another side of the War Zone, its northeastern rim, Don Kemp surveys the neighborhood surrounding his sheet-metal shop on South Carroll and tries to tally the burglaries. One other thing about the crack culture is that it is voracious. It consumes whatever lies in its path and then ventures out in search of fresh prey. In just the past couple of years the dealers and the pushers and the crime that is always at their sides have moved slowly but certainly into Kemp’s neighborhood. It has been hell ever since.

“Glad you came today,” says Kemp, a burly sort with a boyish face. Like many small businessmen in this sector of the War Zone, Kemp is white. But that has not immunized him from feeling the fallout from the War Zone. “They hit us again last night,” he says. “Ripped the tires off a job trailer out back. No problem. They just come by and help themselves anytime they want.”

Kemp and his father, Don Senior, guess they’ve been burglarized at least twenty times in the past five years to the tune of about $100,000 in expensive welding and other metal-processing equipment. Most of that has been taken as a flat-out loss since obtaining business insurance in the War Zone has become next to impossible. “Sometimes they just come in and take a few calculators and office stuff and then pee on the floor for the hell of it,” says Don Junior.

Kemp Sheet Metal Works has operated in this neighborhood for 66 years. Don Senior is still astonished at the fierceness and suddenness of the neighborhood’s transition. “Move out?” he asks. “Sure, you can think about it. But I’d have to sell this place, and who’s going to pay enough that I could afford to move? We’re stuck here. So if something’s going to change, it’s going to have to change here.”

Joe Johnson is a barrel-chested black man with softly graying temples and an electric smile. Like most landlords in the War Zone, the Jamaican occupation has placed him in the grip of a vicious vise: He can stand idly by, accept the Jamaicans’ rent money—often the only rent money—and at the same time watch his neighborhood reduced to slums. Or he can fight the problem and live with perilously low occupancy rates and fear of violence.

Johnson has made up his mind to fight. For almost two years he has served as a one-man cheerleader and activist for the neighborhood. He thinks a big part of the problem has been ignored. The War Zone is not just a police problem, he says; it is a community problem as well. The topography, both physical and social, allows crime to thrive.

Under the circumstances, it is understandable that Johnson didn’t really know where to start improving the neighborhood. He began by taking it upon himself to board up abandoned apartment houses, mow and clean trashed-out vacant lots, and have abandoned vehicles hauled off. But the real answer, he says, would be to get the city to mount an all-out assault on the neighborhood’s landlords.

Unfortunately, the city’s building enforcement code is lumbering and inefficient, especially in a neighborhood like the War Zone, which has always suffered from official neglect. A few vacant buildings have been condemned and demolished, but the process is painstakingly slow and often takes more than a year.

Cruising the Wayside again one afternoon, Nettles had shown me an example. After spotting a rickety flight of stairs without a handrail, he called a fire inspector to the scene. The stairway was indeed in violation of the fire code—action could be initiated to close the motel down if the owner didn’t clear up the problem. But that would take time, said the inspector, a sweet-faced young woman who added that she wasn’t pleased at all to have been assigned the War Zone beat. “It’s not a real good situation,” she said. “I’m white, female, wearing a uniform, and driving a marked car. But I’m unarmed. Put it this way: I try to get my inspections in the rougher areas done before noon.”

Other cities, however, have revitalized dormant, drug-infested neighborhoods. In Miami, Dade County officials blitzed a particularly drug-active apartment complex by using combined investigations by police, building inspectors, and health inspectors. An enormous list of violations was compiled and a suit filed to have the building demolished as a public menace. Houston officials are working with the U.S. Attorney’s Office to attack drug-infested apartment houses via federal statutes that allow seizure of property used for the making and distribution of drugs. But in either case the process is slow and uncertain and filled with loopholes. Under Texas law, for example, property cannot be seized unless officials can prove it was actually purchased with the proceeds of a drug sale.

The problem is also a private one. Most of the property in the War Zone is owned by absentee landlords, including at one time school-board member Thomas Jones and, ironically, three Dallas police officers, assistant chief Leslie Sweet, Corporal Thomas Payne, and former assistant chief Charles Busby. And although most landlords claim they have done all they can to keep an eye on the problem of drug deals in their complexes, police say cooperation has been spotty, particularly since the recession made profits tight. Joe Johnson, for his part, is undaunted. He has even created a neighborhood crime watch. Those have been de rigueur in most neighborhoods for at least ten years, but in the War Zone the idea of citizen involvement tackling crime is novel.

I went to one packed crime-watch meeting in a small church. Those attending seemed to be the neighborhood’s older residents, save a young black who stood at the rear of the church, surveying the proceedings with the shrewd stare of a good eyes. But when Johnson or beat officer Nettles or anyone else rose to exhort the group to remember to do the simplest things—to report suspicious new members of the community, to call the police when something seemed out of hand—few people spoke up, and on their faces I noticed that same old look of resignation. These were people used to giving in and giving up. Johnson says their efforts have pushed many dealers underground in his immediate neighborhood. But he knows the dealers will probably turn up half a dozen blocks away. People like Joe Johnson or R. C. Nettles are not trying to change habits, they’re trying to change a culture.

One reason the War Zone has become a place where even cops walk softly is that the Jamaicans have, in effect, created a kind of crime that is virtually unpoliceable by conventional methodology. All of the technology police have amassed and applied since the sixties is practically impotent in the face of the Jamaicans’ simple but effective guerrilla tactics.

For example, conventional policing these days ties a patrolman to his radio. That allows him to respond swiftly to emergencies, but because many calls aren’t emergencies, it also pulls him away from his beat. In a place like the War Zone the absence of a patrol car for even a few hours can compound the crime problem exponentially. On one occasion Nettles and his partner were called to the downtown Sears to take to jail a thief who had been nabbed by store security. The entire process took a little more than three hours, during which time almost anything could have gone on unpoliced in the War Zone—and probably did. “They’ve got to know we’re there and going to be there,” says Nettles. “This place has to be worked every day. I’ve been wanting to survey my beat apartment house by apartment house to get a handle on just what’s abandoned and who’s living where and where the hot spots are. That’s never been done. But I can’t find the time.”

Undermanned and outgunned, the police have been forced to use high theatrics to attempt to enforce the law. Last spring the police created a special multiagency task force to assault the crack problem in the War Zone. Narcotics officers were sent out undercover to make buys from crack houses, and special tactical squads were assembled to bust them. Since its creation, the task force has netted 289 drug seizures and confiscated more than $250,000 in property and cash. The idea is that if the problem can’t be cured, maybe it can be shocked out of the system. “At least we’re letting them know we’re here. That may not sound like much, but with this situation it’s where you have to start,” says Sergeant Jim Parker, a member of the task force.

Parker is a cherubic, ruddy-faced cop driving the third car in a drug task force caravan that is out on a Friday night to, as he puts it, “bust down a few doors.” Leading the procession is a beat-up white van with a small patched-on sign that says “South Loop 12 Fish Market.” It carries the entry team—half a dozen officers who will storm the targeted crack house. Following are four other vehicles—some marked, some not—to provide backup for the entry team.

Observing a tactical squad’s crack-house bust will firmly convince you that this is war. No polite rap on the door for warrant service here. As the caravan approaches a small, tattered apartment house in the 1600 block of Pennsylvania in the War Zone, the cars pick up speed. The van screeches to a halt in the courtyard, and the entry team is already jumping out of doors, shouting, “This is the police. The police!” and charging an apartment door. A young officer carrying an enormous solid-iron bludgeon leads the way, unhinging the door with two savage blows; a second officer, packing the “big gun”—a nine-millimeter submachine gun—charges through the opening, followed by other officers carrying shotguns. They continue shouting that they are the police. It is melodramatic, particularly considering that the bust will yield the arrest of one candy-faced dealer and the seizure of a few thousand dollars, a few bags of crack, and an automatic pistol. But that’s the point. The police are attempting to get the whole block’s attention—in short, to reeducate a neighborhood to law and order.

The task force moves on to its second warrant, to be served on a small clapboard house where half a dozen dopers are dealing crack. We are half a block away when Parker says, “Look at that—they sure can smell us.” Fleeing madly from the rear of the house are five black youths. Parker rams the accelerator and squeals around the corner to try to head them off. One, two, three blocks we search; it has been all of a minute since we first spotted them. Nothing. The War Zone has swallowed them up.

One black youth, nabbed at the scene, is diminutive and impossibly young, bearing a sullen scowl and a nasty abrasion under one eye—the result of an ill-advised attempt to scuffle with the arresting officers. Since he is apparently nothing more than a hanger-on at the crack house, the officers decide to return him to his home a few blocks away.

As soon as the kid hits the door and sees his mother, he begins pouting and weeping. “Oh, my little boy,” she says. “What have you done to my little boy?” Parker and a fellow officer patiently explain that he was caught hanging out at a crack house, and that’s not someplace a fourteen-year-old ought to be. The mother nods as if she understands, but I leave wondering how soon before that kid will be back.

Our final warrant of the night is to be served in deep Pleasant Grove, a working-class white neighborhood that abuts South Dallas and is in many ways its own war zone. It is the domain of bikers and poor whites, speed labs and violence. As tactical captain Eddie Walt says, “Give me South Dallas any day, but not the Grove.”

From a tactical standpoint, this is the most complex bust of the evening. The house sits back from the road on a boulevard shaded by trees and adjoined by a large, empty lot on one side. The officers don’t know how many dopers they are dealing with or what kind of weaponry they might have. As we cruise up the boulevard toward the house, the tension is thick.

The officer carrying the big gun leaps from the van even while it is still moving. Three white dopers loitering in front of the house are quickly seized, cuffed, and forced to the prone position. They are two females and one male, all in their twenties. One of the females, clearly wired to the hilt, excoriates the officers with a barrage of expletives. “I ain’t no doper!” she screams.

“That makes me feel a lot better,” remarks a nearby officer.

Two more white females and a white male are found inside the house, which turns out to be a true testament to something Nettles has observed on an earlier occasion: “Maybe it’s true that poverty creates drugs. But to my mind, it’s drugs that create poverty.”

Dirty dishes litter the kitchen; the inhabitants have dumped heaps of dirty laundry throughout the rambling home. Police find syringes and other drug paraphernalia stuffed into drawers.

Wandering through a small bedroom past a laundry-littered bed, I notice an infant, no more than six months old, sleeping amid the dirty linen.

“Unbelievable,” I say under my breath.

An officer overhearing me says flatly, “I’ve seen worse. I keep thinking they’ll never surprise me. But they always do.”

While we are riding back to the station, it occurs to me that I have seen law enforcement’s best assault on this new crime wave, and all it has amounted to is the bust of a handful of dealers and the confiscation of a handful of dope and money. Even the cops admit that before the sun rises the next day, replacements will be operating new houses. “It’s like trying to eradicate weeds,” says Parker later. “They grow back pretty much where and when they want to.”

In early September the task force was disbanded and deemed a smashing success. Police subsequently expanded the narcotics division to attempt to keep pace with the Jamaicans. But the law officers may have lost too much ground already. In recent months Jamaicans have been buying up businesses on the neighborhood’s major thoroughfares—gas stations and convenience stores and pool halls. “Consider this,” a police lieutenant said one day. “Consider what it’s going to be like when they start buying apartment houses. It’s hard enough to police now. What if we have to go in and try to bust a rock house that’s owned by a Jamaican?”

It’s another hot and swollen weekday in the War Zone. Nettles and McGuire are cruising up Jeffries again and pondering the future of the place. As in many neighborhoods, it is the kids who provide the clues.

On the right they spy a black kid, cinnamon-colored and tiny, ghetto-strolling up the street. The officers immediately recognize him. Jimmy has been the subject of recent criminal complaints in the neighborhood. Unlike so many others, Jimmy has not been accused of vandalism or petty theft; he has instead been accused of taking younger neighborhood kids at gunpoint to any of the abandoned lots in the area and forcing them—at gunpoint—to have sex with him.

The officers follow Jimmy home and confront his mother with the complaints. “We really wish he’d cut that out,” says McGuire, with well-practiced dryness. Jimmy’s mother seems to agree. As officers Nettles and McGuire continue the lecture, Jimmy wanders around oblivious, insouciant. Ultimately, the cops can do little more than urge his mother to keep him on a tight curfew. “Make sure he stays in this courtyard, okay?” says Nettles.

She nods, and we exit. I ask Nettles how old the kid is.

“He’s ten.”

“What will he be like when he’s, say, twenty-one?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” says Nettles. “The way it is down here, he probably won’t make it that far.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas