Middle school is a time that few people would willingly revisit, but Lorenzo Gomez chose to buck the conventional wisdom. At the age of 38, he decided it was crucial for him to explore a chapter of his life so traumatic that he had blocked it out for nearly two decades.

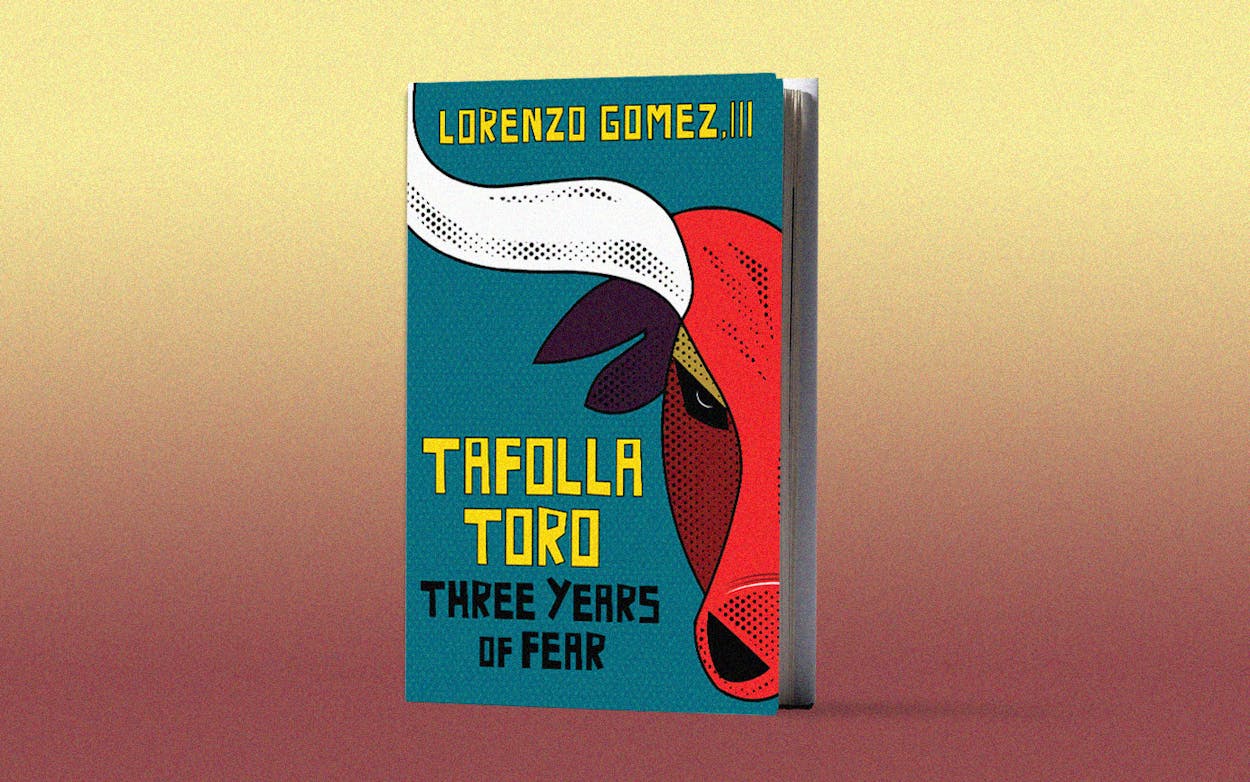

Gomez, chairman of San Antonio co-working space Geekdom and CEO of its content creation arm, Geekdom Media, has just published Tafolla Toro: Three Years of Fear (Geekdom Media), which chronicles his time at Tafolla Middle School on San Antonio’s West Side in the early nineties and the effect those years have had on him. As Gomez writes, that period of his life was marked by encounters with local gangs and the threat of drive-by shootings. In one painful recollection, he details the murder of his uncle.

A therapist helped Gomez work through the experiences he had blocked out and inspired him to assist others grappling with their fears. At the end of each chapter is a letter of advice addressed to his twelve-year-old self. “When you hold on to your fear, it blinds you,” he writes in one letter. “It clouds your vision. You forget about the people around you. Then fear becomes anger, and it’s easier to hate someone than to help them.”

Tafolla Toro is Gomez’s second book, following 2017’s The Cilantro Diaries: Business Lessons From the Most Unlikely Places.

Texas Monthly: Mental health can be a taboo topic, especially in the Hispanic community. Did you have any preconceived ideas about therapy?

Lorenzo Gomez: We didn’t even talk about [mental health] in my family. If you wanted to go to a therapist, it was seen as if you were crazy. That’s why I want people to come away from this book with the message that your mental health is really important. People go to the gym to get in shape physically; you can do the same thing for your mind.

TM: What lessons did you want to share with your readers?

LG: I fought the process at first. I didn’t want to be in therapy, but that changed when I found a great counselor. Now I use the principles I learned every day, and I wanted to include them in the book without having younger readers feeling like I was lecturing them. Instead, I wanted them to be able to relate to my experiences and learn to deal with the past in a healthy way. You can decide at any moment to change your behavior. You’re not necessarily bound by the things you’ve done before.

TM: Your book delves into a lot of the violence you witnessed in middle school. How do you think those experiences have affected your life?

LG: One of the negatives of seeing violence that young is that I viewed all conflict as a bad thing. Years later, in friendships and relationships, if conflict was on the horizon, my inner twelve-year-old felt like it would inevitably lead to violence. Now I’ve completely reframed that line of thinking. There were some positives to witnessing all that violence, though.

TM: Like what?

LG: It made me more at ease with taking risks. I’ve put myself in some of the riskiest situations out there, and it’s because I think, “What’s the worst that could happen?” I saw some really violent things in my life and made it out, so it helped me be more bold.

TM: The book dives into a really painful time in your life. Were there any moments you were scared to get into?

LG: The murder of my uncle was the part I was very nervous about because I wanted to be very thoughtful about it, and I wanted to be respectful of his memory. I wasn’t nervous about exposing my fears and anxiety. The power of the things that scared me was taken away because I wrote about it and talked about it. I can look at it objectively and put it in its place. I can make it useful.

TM: When you were growing up in San Antonio, the West Side was much more violent than it is now. How does your vision of the West Side of your childhood square up with the way you view the area now?

LG: When I was writing about it, I struggled because I was trying to describe an entire neighborhood, and I realized that my twelve-year-old self believed that everybody who lived on the West Side was bad and violent, and that’s just not true. I wanted to hit that head-on in the letters, and say, “You were afraid of people in the West Side because there were people there that hurt you and your friends, but there were so many others who were just going to school and studying hard.” You tell yourself this false story about an entire group of people, and you see that happen all the time in the world. I thought it was important to tell myself and the reader that you need to check those feelings because they lead to some very bad worldviews.

TM: How was your experience growing up in the West Side different than that of some of the people you went to school with?

LG: I grew up in a two-parent household. Both of my parents worked. But immediately across the street from us was a family where the husband shot his wife after an argument. Both of these stories exist on this one street, so to say the whole area was bad is just untrue. When you grow up in a neighborhood like that, the tendency is to say, “I’m not like this, I need to get out.” My parents tried to be a positive light and do whatever they could to better the world around them.

- More About:

- Books

- San Antonio