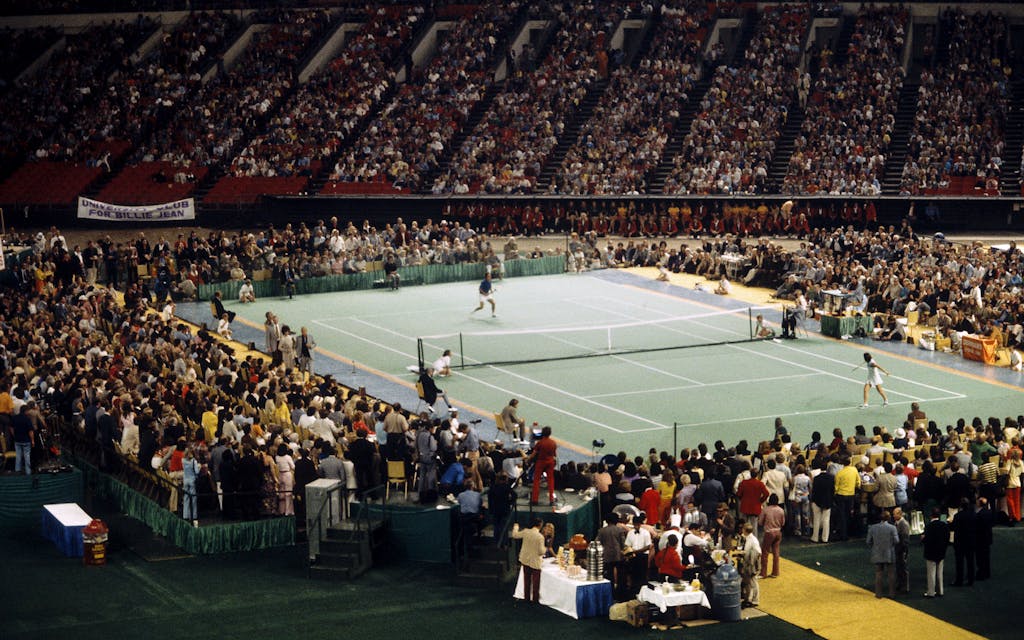

On the evening of September 20, 1973, an estimated 90 million viewers across the world, including more than 40 million in the United States, a fifth of the country’s population at the time, turned on their TV sets and sat down to watch a tennis match. The coverage began with the famous voice of sportscaster Howard Cosell announcing, “Live from the Astrodome in Houston, Texas, the tennis ‘Battle of the Sexes,’ Billie Jean King versus Bobby Riggs.” Cosell described the atmosphere as “a wild scene almost reminiscent of college football. With the celebrities present. With the big band here. With dancing cheerleaders and all of the rest.”

Of course this circus was happening in Houston and in the Astrodome. Women’s professional tennis was launched in 1970 in the Bayou City, almost exactly three years to the day before the “Battle,” when nine players, including King, signed contracts to each earn one dollar to play on the new Virginia Slims tour. “The ‘Battle of the Sexes’ is a culmination of the launching of women’s professional tennis,” says Frank Guridy, author of The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics. “You had this kind of outside-the-box entrepreneurial spirit that was circulating in the Texas sports scene at that time.” The Astrodome, part hulking monstrosity and part modern marvel, may have been the best example of that attitude. Just eight years old in 1973, the venue was the first stadium to be fully enclosed and air-conditioned, to have luxury boxes (based on the design of the Roman Colosseum), and to have its own fake grass (Astroturf, obviously). Muhammad Ali won four bouts there between 1966 and 1971; Elvis set an attendance record there in 1970 when he played six shows for more than 200,000 people; Evel Knievel jumped thirteen cars there in 1971.

That night in 1973 under the dome was a circus worthy of this new-age Colosseum. King, 29 years old and one of the world’s top women tennis players, made her entrance wearing her trademark glasses and a sweater over her collared tennis dress, with shirtless men carrying her into the famed arena on a litter adorned with giant pink feathers. Riggs, wearing a yellow jacket with the large red lettering of the caramel candy “Sugar Daddy” on the back, was carted out on a rickshaw pulled by women dubbed “Bobby’s Bosom Buddies.” He wasn’t about subtlety. He was 55, three decades past his last grand slam title, and happy to say whatever misogynistic thought ran through his mind anytime a microphone was present. When Johnny Carson asked Riggs before the match if he liked women, Riggs responded, “I like ’em real good in the bedroom, the kitchen . . . I really think the best way to handle the women is to keep them pregnant and barefoot.”

Riggs was the perfect male-chauvinist foil to King’s feminist stance, each a stand-in for one side in the larger battle over women’s rights taking place in the early seventies. In the eighteen months before the “Battle,” Ms. Magazine launched, Title IX became law, the Equal Rights Amendment was sent to the states for ratification, and Roe v. Wade gave women the right to access abortion care. But women still couldn’t get credit cards in their own name, they could be fired for being pregnant, and they had no legal recourse for sexual harassment at work. In her recent autobiography, All In, King writes, “I became a symbol for people who were tired of seeing women dismissed en masse, demeaned as second-class citizens and shut out of opportunities everywhere, not just sports.”

It was so much more than a tennis match. But it also mattered that it was just a tennis match. “The great thing about a match like this is it’s man-versus-woman and somebody’s gonna win. There are very few events that crystallize that as well,” says Susan Ware, author of Game, Set, Match: Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports. Sports are simple. Competition boils down the complex into a set of rules and demands a winner. There are no do-overs. Everyone who tuned in that night knew that at the end of the match, a man or a woman could declare victory and, in turn, so could men or women more generally.

After the pre-match festivities, it was King and Riggs across the net, in front of more than 30,000 people, the largest tennis audience ever to that point. Rosie Casals, King’s friend and fellow tennis player, battled sexist commentary in the booth. In 2017, Casals recalled about Cosell, “I know he didn’t think that women belonged in the booth, that’s for damn sure.” Part of what made the entire spectacle so powerful was the juxtaposition of the sexist remarks from the commentators and the TV producers’ decision to focus on beautiful women in the crowd alongside what they were they were hearing from Casals and seeing on the court: King’s dominant play and the brilliance of her backhand. The real-time, “in-your-face sexism while watching this athlete dismantle these stereotypes,” Guridy says, was a potent combination.

King whooped Riggs in straight sets: 6–4, 6–3, 6–3. When Riggs’s final shot landed in the net, King threw her racket up toward the dome in celebration. She had won. Women had won.

Today, the “Battle of the Sexes” turns fifty. King has said that every single day since the “Battle,” someone has mentioned it to her. Women want to tell her about their excitement over her win and how watching her trounce Riggs gave them confidence, while men say it caused them to question their assumptions about women.

What some of those well-wishers might remember, though, is that the “Battle” was actually the last part of a dizzying trifecta of athlete activism in 1973. That summer, eighty men’s professional tennis players boycotted the tournament after an international governing body refused to let a player compete because he chose not to play in another tournament. Seeing the men use collective action to protect themselves convinced King that women needed to do the same. A week before Wimbledon, she gathered 65 women’s tennis pros in a large meeting room in the Gloucester Hotel, had a player block the door, and presented everyone with bylaws. They hashed out the details and created the Women’s Tennis Association, which is still the worldwide governing body for women tennis players. King then went out and played at Wimbledon, winning not only the singles title, but also the women’s and mixed doubles championships.

Later that summer, the U.S. Open produced the next breakthrough: an announcement that women would be paid the same as men at the upcoming tournament. The previous year, King had put the wheels in motion for this. After winning the 1972 U.S. Open, where King earned $15,000 less than her male counterpart that year, she told reporters that the unequal pay “stinks” and that a few dozen of the top women players had considered boycotting the tournament that year. She met with the U.S. Open director and said she’d boycott in ’73 if he didn’t fix the issue. She even helped raise the money to achieve pay parity. In All In, she writes, “I told him I had lined up a sponsor—a Bristol-Myers brand, Ban deodorant—to kick in the extra $55,000 to achieve the equal prize money we were seeking. He made the deal.” And so, in 1973, the U.S. Open became the first grand slam with equal prize money for men and women. The Australian Open didn’t offer equal prize money until 1984, and even then, the purses for men and women fluctuated and were not always equal over the next seventeen years. Equal pay was not cemented Down Under until 2001. The French Open caught up in 2006, and Wimbledon, finally, in 2007, more than three decades behind the U.S. Open.

Fifty years on, Guridy says the “Battle of the Sexes” remains relevant because we’re “still dealing with gross inequalities across the board along gender lines in the women’s sports scene. You’ve got this paradox of an explosion of women’s participation in sports, women’s sports being a business and successful. You say, ‘Wow, look at all the progress.’ But you don’t have women controlling women’s sports.” Ware agrees: “Many of the issues that [the ‘Battle’] raised, like equal pay and respect for women athletes and media coverage and whatever, there has been progress since 1973, but nowhere near as much as I think any feminist would’ve thought in the seventies.”

Ware notes that the other two women’s sports milestones of 1973—the creation of the WTA and equal pay at the U.S. Open—get overshadowed by the “Battle of the Sexes” because the latter was a huge popular culture moment, but they were just as impactful. “Now we see how women’s tennis has prospered in a way that other women’s professional sports have not,” she says. “I think in large part that comes from them having a strong union, a strong base of support, and a common cause.” Equal pay at the U.S. Open, in particular, sticks out for her. “We know that it was the only place that happened. That women didn’t get equal pay on the job or in Congress or any other place. There at the U.S. Open, they did.”

It would be a long time before women in other sports would catch up, and most of them still have not. Sure, the U.S. women’s soccer team finally secured equal pay after a nasty fight with U.S. Soccer, but that was only last year, and it only applies when they are playing for the national team. The landscape in professional soccer or even at the World Cup is one of massive disparity. And if you thought equal pay in tennis was settled, it was only seven years ago that Novak Djokovic, the number-one men’s tennis player then and now, said prize money should based on who gets more butts in seats and that the men’s tennis organization “should fight for more because the stats are showing that we have much more spectators.” (He issued a clarification but it did little to clarify anything.) Outside of the grand slams, Djokovic need not worry. A recent Sportico report found that “the pay gap in tennis exists basically just as it did in 2007.”

Still, it’s not hyperbole to say that much of the progress made in women’s sports can be traced back to King’s activism over just a few months in 1973, capped off by her win over Riggs in the Astrodome. This was made clear earlier this month, when nineteen-year-old Coco Gauff won her first U.S. Open title at the Billie Jean King Center in Queens, New York. An audience of 3.4 million viewers tuned in to see her do it, which ESPN says made the match the most-watched women’s tennis final in history. (Gauff’s victory also drew a million more viewers than Djokovic’s win the next day.) King was at the women’s final, decked out in a glorious collared purple jacket and wearing matching frames, to hand Gauff her trophy. Then, when Gauff was given her check for $3 million in prize money, equal to Djokovic’s purse, she leaned into the mic and said, “Thank you, Billie, for fighting for this.”

Gauff laughed and the crowd roared. This was quite a different spectacle than the one the Astrodome hosted fifty years earlier. This one was King’s own in the making. And again, she won.