William Middleton’s long-awaited Double Vision: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil (Knopf) finally arrives March 27. The first-ever biography of the legendary art patrons—whose namesake Houston museum has been drawing visitors from around the world since it opened in 1987—is a veritable tome; Middleton, a journalist and editor who’s spent much of his professional life between Paris and New York, relocated to Houston to complete the nearly 800-page book, which he toiled on for over a decade.

We recently caught up with Middleton by phone to talk about the process of writing the book and the Menils’ legacy in Houston.

Texas Monthly: At what point did you decide you needed to move to Houston to do this properly?

William Middleton: My first feeling was that I needed to be in Houston because most of the research materials were there. But once I lived there for a while, I began to really understand Houston and Texas. It’s a very particular sort of place, and it’s I think it’s important to understand what it was like in 1941 when John de Menil first arrived.

It sounds like such a cliche, but there’s a sense of optimism [in Houston], a sense of “let’s just get it done.” I lived in France for ten years, so I like France a lot, but France is very funny. In Paris, when you propose something the first answer is always no. No, that’s not possible. No, we couldn’t possibly do that. Eventually you talk a while and you convince people, but I think Houston’s sense of yes, we can do anything, was important to the Menil spirit.

TM: What was Houston like when the Menils arrived in the 1940s?

WM: It’s not that there was nothing there. There were pockets of sophistication. There were always people in Houston who traveled a lot, and who were aware of what’s going on in the world. But compared to Paris or New York it didn’t have much.

TM: There were a number of points in their lives when the Menils could have switched their focus to New York or Paris. Why did they stick with Houston, despite the occasional resistance to their liberal politics?

WM: Dominique assumed that after John retired they would return to Paris, where she had her family. And he just said, no, this is where we are, we started here, and we’re going to stay. Lois, their daughter-in-law, said that after that Dominique never wavered. She was completely committed to Houston. She has this quote: “What do Paris or New York need with another museum?” They felt like they were needed in Houston. And I’ve never seen anything, any note, any letter, that suggests Dominique wasn’t happy there, or that she viewed it as a sacrifice. She was fully committed to it.

TM: Why are the Menils important enough to merit an 800-page biography?

WM: The size of the biography is dictated by the size of the lives. In this case, it’s a joint biography, so you have two family histories. John de Menil was born in 1904, and Dominique died in 1997, so the book covers the entire twentieth century. It’s set in Paris, New York, Houston, and several other cities.

TM: You detail extensive family histories for both John and Dominique. Why was that so important to you?

WM: Well, they didn’t just drop out of the sky. They were the product of a very specific background, and to understand what they did in Texas you have to understand where they came from. They came from a very big world, and they arrived in a place that had very little. Instead of complaining about that or being depressed, they took a look around and said, let’s do something about that.

TM: How would you define the significance of the Menils in twentieth century art history?

WM: Well, they built the most important collection of Surrealist art in the world. I think the expanse of their collection is also rare—often collectors limit themselves to two or three areas, and collect in depth in those areas. The Menils, as you know, collected everything from prehistoric to contemporary pieces, and they were just as passionate about a Cycladic object as they were about Andy Warhol’s electric chair series. The scale of the collection is also significant—there are very few people who buy 10,000 works of art. And they built a free museum so Houstonians could see it.

TM: What would Houston look like today if the Menils had never come?

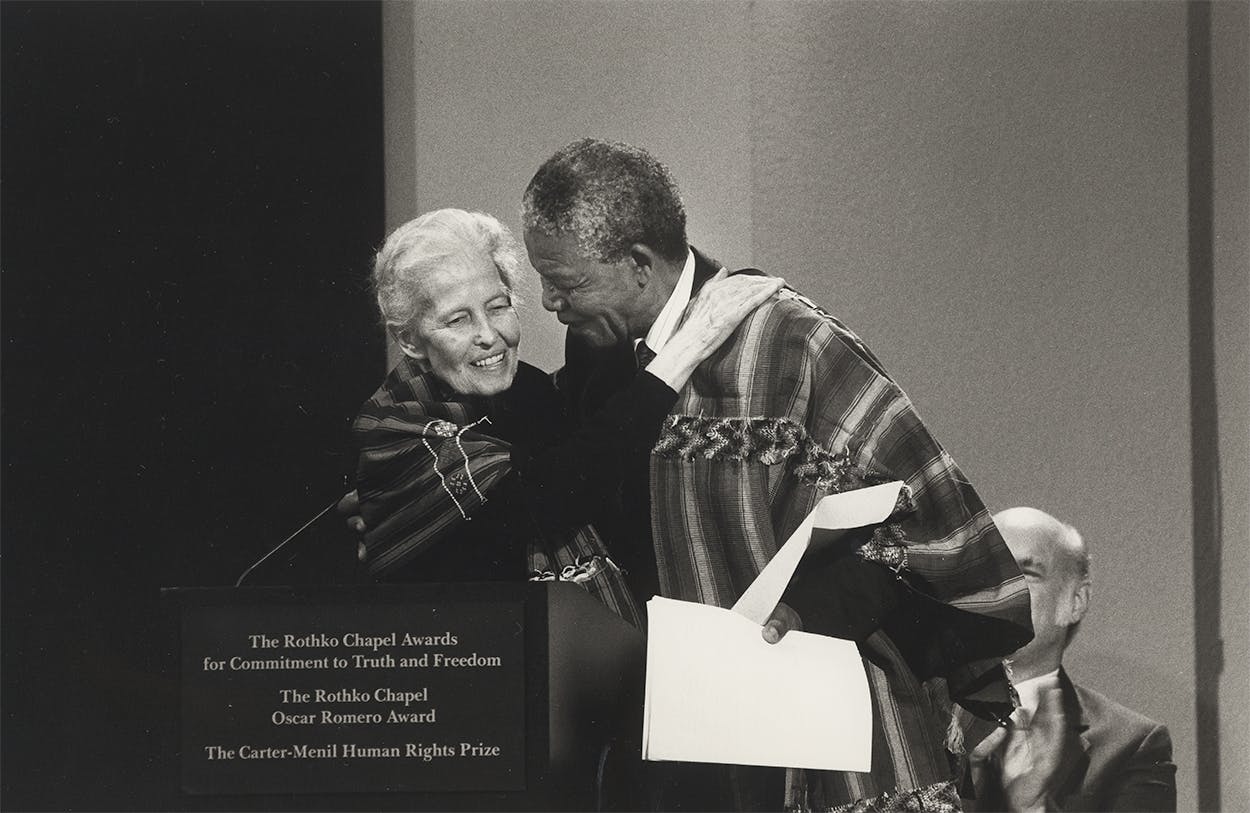

WM: We think of the Menil Collection and the Rothko Chapel, but look at what they did for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Look what they did for the Contemporary Arts Museum. The first exhibition they did was a 1951 Van Gogh show at the Contemporary Arts Museum. So they worked with collectors around the world and they ended up getting 21 Van Goghs down to this “potting shed,” as someone called the museum. It was the most exciting cultural event ever seen in Texas. So from the very first thing they did, they said it’s not just going to be good for Houston, or good for Texas, it’s going to be good by international standards, New York standards. And I feel that when you have one institution insisting on that, it helps inspire everyone. They raised the level for everyone.

Middleton will embark on a book tour, which includes multiple Texas stops, on March 27.