An interviewer once asked the late choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey if he’d had to sacrifice anything. “Everything,” Ailey replied without hesitation. “Dancing presents an enormous sacrifice. I mean, it’s a physical sacrifice. Dancing hurts. We don’t make that much money. When we tour, it’s six months out of the year; it’s disastrous on any kind of personal relations. It’s a tough thing. You have to be possessed to do dance.”

This revealing conversation, presented early on in Jamila Wignot’s new documentary Ailey, sets the tone for a remarkable take on its titular subject. Ailey, who died in 1989, gave himself over to found one of the most renowned dance companies in the world. He envisioned timeless works that continue to be staged around the globe, and he often drew on his experience as a Black man growing up in 1930s-era Rogers, Texas. Through this, he nurtured a practice that not only centered Black dancers—so often excluded from ballet—but allowed them to actively shape its trajectory, too. “I wanted to do the kind of dancing that could be done for the man on the street, the people,” Ailey says in the documentary. “I wanted to show the Black people that they could come down to these concert halls, that it was part of their culture being done there.”

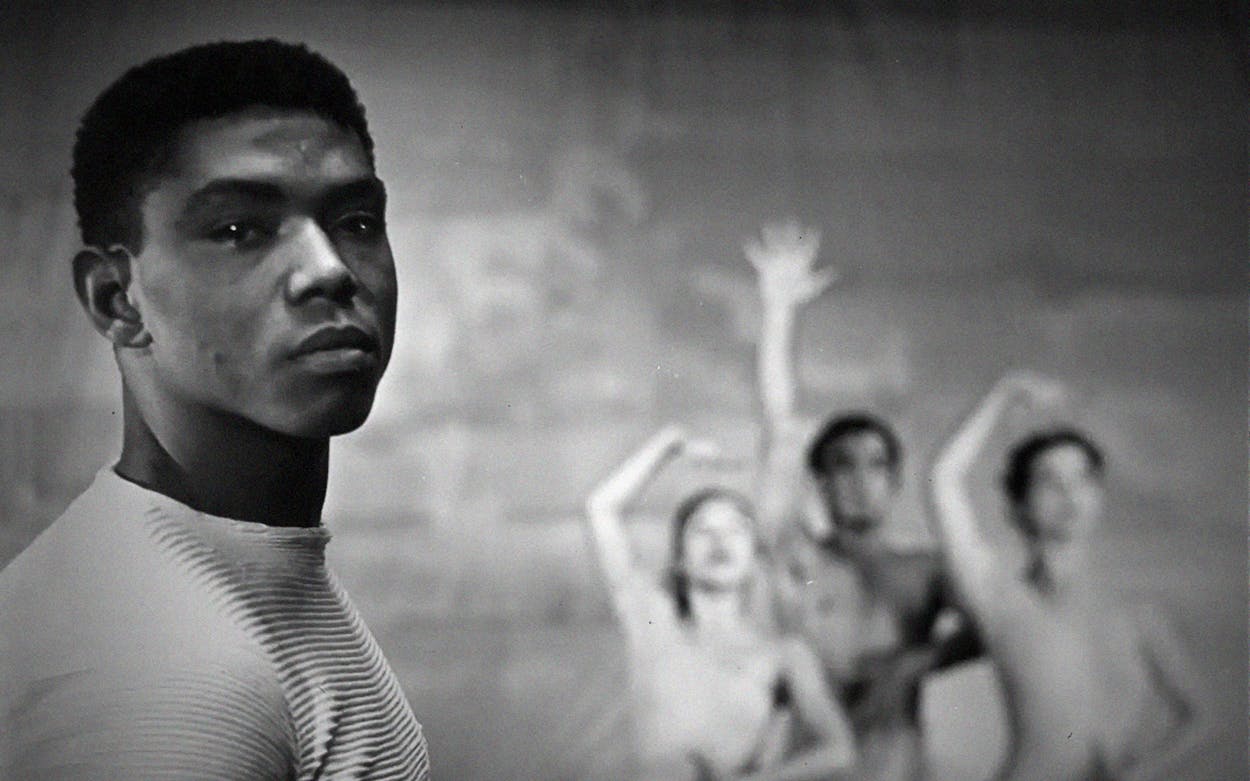

Screening in Texas starting this weekend, the film melds detailed voice-over interviews with Ailey; candid, sit-down chats with friends and collaborators; amateur home-movie footage; and rehearsal tapes of contemporary Ailey dancers as they prepare to stage Lazarus, a work informed by his life that premiered in 2018. Ailey is immersive and impressionistic in equal measure. It doesn’t follow the typical chronology that’s often at the core of a documentary; there’s no detailed play-by-play of the dancer’s upbringing.

But the film doesn’t need that to be moving. Wignot’s choice to have Ailey tell the story in his own words is complicated by challenging interviews with those who knew him best—these friends and colleagues sometimes have a different take than Ailey’s. This structure allows viewers to draw their own conclusions. “I’m interested in how you can be almost in somebody’s body experiencing their life and what that means, and that there’s space for me, as the viewer, to do some thinking on my own and have subtext,” Wignot tells Texas Monthly. “Which is difficult in a documentary.”

Ailey’s legacy is well established in New York City, where he spent much of his adult life and founded his theater. But his native Texas, and his complicated relationship with it, informed how he saw the world and the work he went on to do. Born during the Great Depression in the rural Bell County town of Rogers, Ailey recalls being “glued” to his mother’s hip as they traveled around the region “looking for a place to be.” As a child, he picked cotton in the fields alongside his mother; she also cleaned houses for white families in the area. Ailey would later recall this time when producing his monumental work Revelations (1960), drawing on what he referred to as “blood memories,” visceral impressions that were as much a part of his body as the blood coursing through his veins. Ailey’s memories, and the distinct way he imbued them into emotive movements onstage, became a crucial influence on Lazarus choreographer Rennie Harris decades later. “I see the dancer as the physical historian,” Harris says in the documentary. “The dancer holds the information from the past, the present, and the future. Why a particular movement was particular or important; why it was valued in a community.”

As a child, Ailey found himself drawn to house parties and local honky-tonks where his neighbors, family members, and friends would let loose and dance together. “This is where we let it all hang out,” Ailey remembered. “It was a time when people didn’t have much, but they had each other.” He drew on this experience for his ballet Blues Suite, a performance that launched his company, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, in 1958. Set in a “sporting house,” or a brothel, the piece follows individuals drinking and dancing at the joint until morning church bells signal that it’s time to go home and get ready for Sunday service.

Blues Suite loosely reflected that sorrowful, albeit joyful, time in Ailey’s life, presenting “the problems but the romance,” as he describes it. For Wignot, this interplay was critical to the documentary. “I want people to understand the brutality of Jim Crow Texas, in the first decade of his life,” Wignot says. “I also want people to understand what defines Black life—and that is not the brutality. What defines it are these spaces that we create where we can have relief, where there is music and there is church. It’s a complex experience. And I think it is foundational to his work, and to his identity as a person.”

When Ailey was twelve years old, he and his mother decamped to Los Angeles. He caught a performance by the touring Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and soon it became a ritual for him to venture downtown and watch dance shows. Something was missing, though. “There was nobody Black, nobody to model oneself after,” he remembers in the film. But when Ailey had the opportunity to see trailblazing Black dancer Katherine Dunham, he was “taken into another realm” by the way she pulled from Afro-Caribbean, blues, and spiritual traditions. “Dance started to pull” firmly at Ailey after that, and he started making up steps as he played on the grass.

Wignot had a formative experience of her own while seeing an Ailey company show years ago in Boston, where she attended college in the 1990s. For her, the performance was revelatory; it provided “a counter-narrative to the ways that you experience life as a Black person in the United States,” she says. “The capacity to share experiences in a nonverbal way, and the expressive possibilities that are there on the stage, just really blew my mind.” She remained a fan of the company’s work for years, but didn’t know much about Ailey’s story until Insignia Films approached her in 2017 to potentially helm a documentary about him. As she conceptualized the film’s approach, Wignot gravitated toward telling Ailey’s story less through a head-on biographical approach and more through exploring the idea of movement itself. “Could we tell a story that somehow tried to capture what dance does?” she asked.

Interviews that Ailey recorded during the last year of his life were key. But by also including Ailey’s friends, collaborators, and fellow dancers, Wignot offers a more nuanced portrait. Near the end of the film, Ailey’s friend, the dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones, speaks about how the public held Black dancers to an impossible standard. That was especially true during the AIDS crisis, even as Ailey himself fell ill and eventually died from the disease. As Jones speaks about the shame surrounding AIDS, and the fact that white arts patrons often ignored the crisis, the film cuts to Nancy and Ronald Reagan. They were all smiles as they shook hands with Ailey during his Kennedy Center Honors the year before he passed away, even though the Reagan administration had spent years declining to acknowledge or act on the epidemic. “Men are men on the Ailey stage, and women are women on the Ailey stage,” Jones says. “And they are exemplary, and they are the survivors of racism and slavery, and they are beautiful and they are strong, and they will live forever and leap higher and higher. Are you telling me that they have sex that could kill them? Are you telling me Mr. Ailey himself? Oh, that’s too much; we have to edit that out of the history.” Jones believes that Ailey “participated in the editing of” that history, too, by distancing himself from other gay men who were grappling with the same disease.

Friends and fellow collaborators also discuss how, even after working with Ailey for decades, he kept those closest to him at arm’s length. His friends say Ailey struggled with the pressures of having to constantly create and innovate, particularly as a Black man in the spotlight; it eventually took a toll on his mental health. The film suggests that Ailey wasn’t truly close with anyone save for his mother, who always supported his career, and that he was lonely. The film often circles back to the idea that despite providing an outlet for profound freedom, as much for the dancers as audiences, Ailey himself didn’t feel fully free. “We just are left with that as a reality of who he was: a person who gave so much to his work, to the people around him, and who wasn’t able to receive the kind of love he put out,” Wignot says.

Still, that love reverberated through everything Ailey went on to do. As a young dancer, Ailey studied with the late choreographer Lester Horton; there, he learned “not just to do a plié but to give it an emotion,” as he once put it. That valuable lesson became a through line in his work, particularly in Revelations, a propulsive performance that pulled from his upbringing in the church, with scenes depicting his own baptism and the experience of gathering to worship on a scorching day. The documentary dwells on Revelations, with good reason: it’s regarded as one of Ailey’s masterpieces, an achievement that changed his career and has gone on to become one of the most-viewed modern dance performances in the world, experienced by an estimated 23 million people in over seventy countries around the globe.

Revelations also transformed the lives of Ailey’s contemporaries and collaborators. Choreographer Mary Barnett, who would go on to become a rehearsal director for Ailey’s company in the mid-seventies, was moved to tears the first time she saw Revelations performed live. It was unlike anything she’d seen or studied in dance; “this was more of a reenactment of life,” as she says in the film. “Alvin entertained my thoughts and dreams that a Black boy could actually dance,” adds George Faison, who danced for the company in the late 1960s. “It was a universe that I could go into, I could escape to, that would allow me to do anything that I wanted to.”

Not that dancing with Ailey was easy. Those who studied under him remember the man as both exacting and encouraging, relentless in pursuit of drawing out the greatness he knew his students possessed. Ailey posits that his impact is still deeply felt decades on, at once by his collaborators and by those who never met him. “The exchanges that all of us had were full of large embraces,” says dancer and Ailey artistic director emerita Judith Jamison in the film. “If he was talking to you from fifty feet away, you would feel that embrace, you would feel that comfort that you could make an absolute fool of yourself . . . you would feel safe to extend yourself enough so that you felt free.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Documentary