Though Daniel Johnston is best known for his music, he was also a prolific visual artist who created thousands of drawings and sketches. By far the most famous of these is Hi, How Are You, the now-iconic black and white image of a frog with eyes that look like antennas. Originally drawn for the cover of Johnston’s 1983 cassette, Hi, How Are You: The Unfinished Album, the frog and his friendly question still adorn a brick wall at Guadalupe and Twenty-first streets near the University of Texas. Johnston painted them there 28 years ago, and though the Sound Exchange record store that commissioned the mural is long gone, the art is world-famous. Kurt Cobain wore it on a T-shirt for several public appearances, and last year the streetwear brand Supreme released a shirt featuring the work. Since 2018, Austin mayor Steve Adler has declared January 22, Johnston’s birthday, to be “Hi, How Are You Day,” a mental-health awareness effort led by a nonprofit, the Hi, How Are You Project. It’s clear that the image still resonates—but the sheer scale of its success also threatens to flatten Johnston, who died at 58 in 2019 of a suspected heart attack, into a bumper sticker or an Instagram post. He risks becoming a symbol, rather than a complex, flawed human being and serious artist worthy of critical consideration.

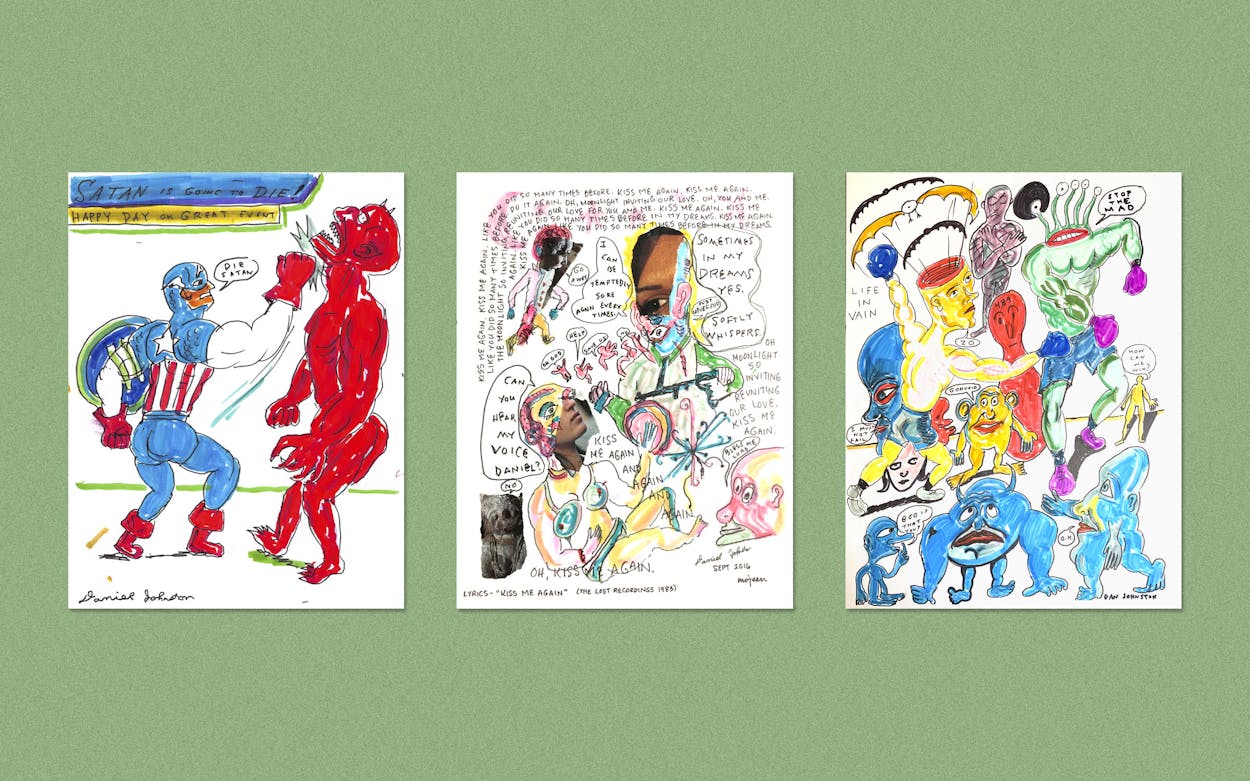

Thankfully, a new exhibit pushes back on that. On view through July 31 at Dallas’s Ro2 Art Gallery, “Story of An Artist & Songs of Pain” features 179 mostly never-before-seen artworks by Johnston. Sketched with cheap colored markers on found paper, typing paper, and cardstock, the drawings are mostly legal pad–size. Enigmatic and full of the same raw energy and sincerity that attracted fans to Johnston’s music, these works deepen our understanding of Johnston as an incredibly prolific, world-building artist.

Johnston struggled with severe mental illness throughout his life. Depending on which doctor he was seeing, his diagnoses included schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic episodes. These challenges didn’t hold him back from writing and recording catchy, confessional lo-fi ballads like “True Love Will Find You In the End,” earning him a cult following in the indie music scene of the 1980s and ’90s, when he lived in Austin. But visual art was his first love, says his sister, Marjory Johnston.

“He wanted to be a comic-book artist,” says Marjory. She was the primary caregiver in Daniel’s last years, and the art in the exhibit comes from her personal archive. “The songwriting was not his main thing when he was very young. He was both all the time, but people noticed the songs before they noticed his art.”

Like his music, Johnston’s drawings display an overwhelming sincerity and are replete with authentic emotion. One work is titled Guilt and Shame; he’s grappling here with Christianity and morality, common themes in his lyrics. At the same time, the imagery—four floating, headless bodies and a row of eleven severed heads—is unlike anything in his songs.

A section of the show features collaborations between Daniel and Marjory. The two worked together for the last four years of his life, and these later pieces feature collages and handwritten lyrics to entire songs. Daniel did the drawings, and Marjory wrote the lyrics and sometimes did the coloring.

In Johnston’s last years, fans and critics often considered him to be an artist in decline, weakened by decades of mental illness and intense psychiatric treatments. But these collaborations, which include one of Johnston’s last drawings, Life in Vain, clearly show artistic progression, particularly with his use of collage. Taking up as much room as the imagery, the lyrics to entire songs also tie the drawings directly to Johnston’s music. Viewing a Daniel Johnston song, perhaps while listening to it with headphones, is a unique gallery experience offered by these rarely seen works.

Johnston constructed a rich imaginary world with his art. Along with strange versions of superheroes like Captain America and the Incredible Hulk influenced by the style of comic-book artist Jack Kirby, the drawings include anthropomorphized frogs, mice, and ducks. The stream-of-consciousness imagery has enough symbolic visions to warrant its own dictionary, although the meanings are hotly contested by fans. The drawings include numbers, reflecting Johnston’s interest in numerology; frequent battles between good and evil; and references to his Christian faith, often with images of Satan. Some words are misspelled by accident, while others indicate dual meanings. Johnston’s fascination with eyeballs is prominent throughout his work. His frog starts out with two eyes, but eventually has several to indicate that he has lost his innocence by seeing too much of the world.

“His art was unfiltered—whatever came out of his head,” says Ron English, who collaborated with Johnston for twenty years, both as an artist and a musician. “He understood his image, but he wasn’t thinking about who his audience is or the market.” English remembers seeing Johnston’s lack of enthusiasm while he did an interview for Rolling Stone: “It was always just the raw, real him. That’s quite unusual for an artist or a musician.”

Johnston became known as an outsider musician, but he was not necessarily an outsider artist. The term refers to self-taught artists—often recluses or those struggling with homelessness or poverty—who lack formal training and are disconnected from the art world. Though his drawings reference mental illness and may not look like the work of a trained artist, Johnston studied fine art in college at Kent State University’s satellite campus in East Liverpool, Ohio. “He’s an insider artist,” says Jeff Feuerzeig, whose 2005 documentary on Johnston put equal emphasis on his music and his art. “But he was unfairly tagged by lazy people who don’t know the history of art. He is on the level of Pollock, Warhol, or Duchamp. He was something brand-new, and people don’t always understand brand-new when they confront it.” Feuerzeig’s film, The Devil and Daniel Johnston, won an award at the Sundance Film Festival and helped create interest in Johnston’s art from galleries across the globe.

“He created thematic visionary art,” Feuerzeig says, adding that the drawings frequently address Johnston’s life, spirituality, art history, and history in general. Works like Calling All Girls from the ’90s, for example, show a plethora of influences. A large, surrealist head with hazy eyes in the background makes the image psychedelic and activates the unconscious mind, but other characters in this work are more concrete, like figurative nudes and cubist box-headed men.

Johnston created hundreds of thousands of works, including about 10,000 meant for future collaborations with Marjory. Feuerzeig once saw several enormous trash bags full of drawings in the garage of Johnston’s family home. Though Johnston’s art could sell for thousands of dollars during his lifetime, he often handed out stacks of drawings for free or traded them for comic books and rides to fast-food restaurants.

While touring with Johnston, English saw him give countless drawings away, which sabotaged his art career. “How can an art gallery with an expensive storefront in Chelsea put in all that effort and try to get top dollar for your drawings when everyone with a comic-book store has a big stack of them under the counter?” English asks.

But “Story of An Artist & Songs of Pain” highlights some of the best pieces from one of the largest collections of Johnston’s work. And with wildly inventive Magic Marker color schemes and a cryptic cast of cartoon characters, Johnston’s drawings created a world worth exploring—the visual equivalent of his songs. Fans who are only familiar with his music have experienced just half of the endearing universe he created.

“The collaborations are a good place to start if you are a fan of his music but don’t know about his art,” Marjory says. “But you will recognize the same person you have been listening to in his art. There’s a naive quality and a wise quality. He was an extremely rare jewel of a soul, and people enjoy being around it.”