This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

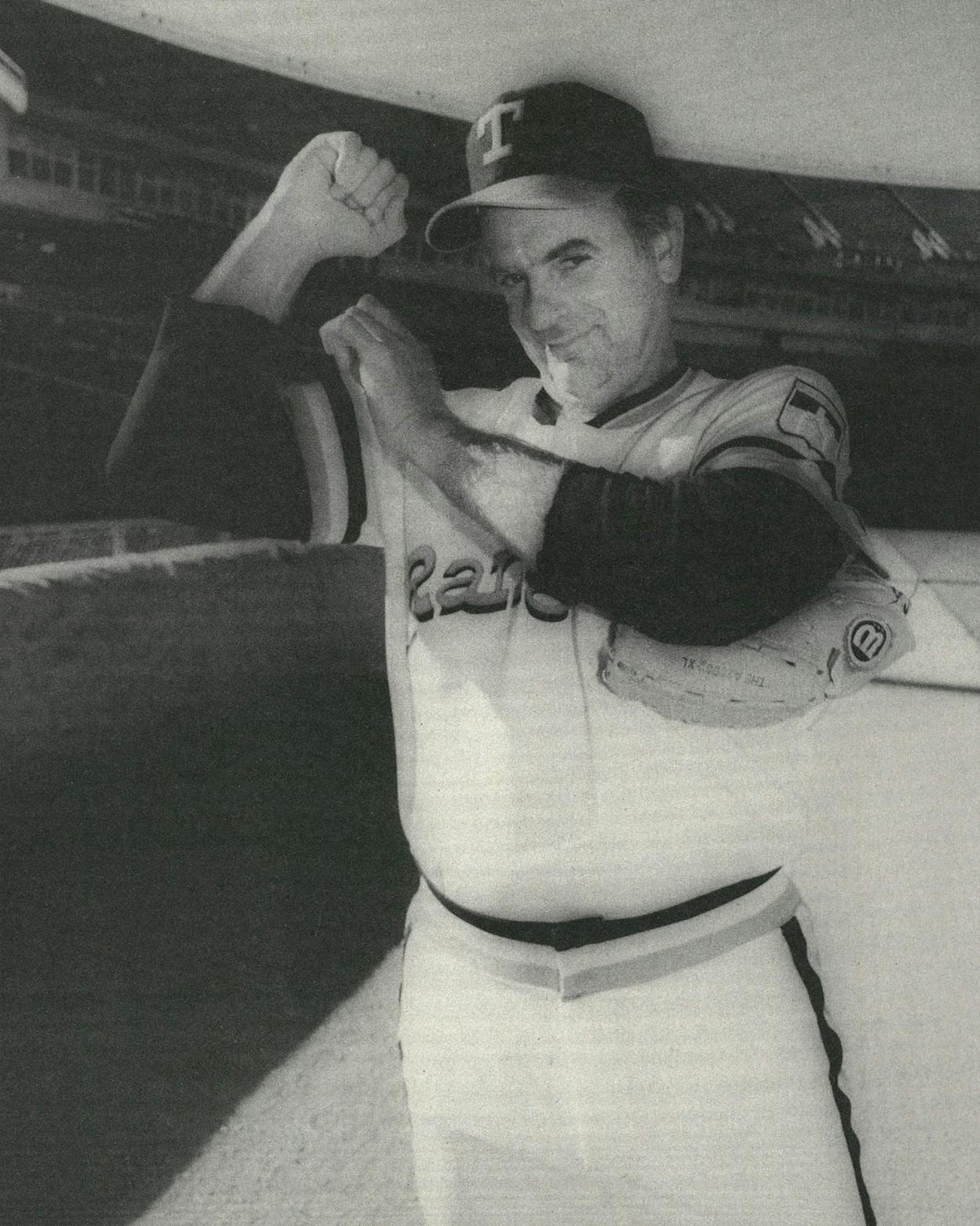

The end of the bench is Perry land. The fan’s eye scans the roster of springtime faces in the dugout until it comes to the old man in the blue jacket, keeping warm on an impossibly hot day, staring blankly into the near distance where opposing batters present themselves to his imagination. With his cap pushed partly back you can see his eyes, which are so bright they are nearly colorless, and above them the rise of a shiny bald dome. He does not shave between pitching assignments, and his beard, stark white, gives him an air of disrepute, like one of the sorry old men who surprise you out of alleyways. Showered and shaved, he is transmogrified into the respectable farmer he is in the off-season, which is to say that he is powerful without being muscular, with a nice, soft overlay of prosperity. But at this moment, when he is waiting to resume the mound, he is forbiddingly intense and ill-humored, and the youngsters at the other end of the Rangers bench would no more cross his line of sight than they would poke a toe into a snake hole.

The 1980 baseball season will conclude after Gaylord Perry turns 42, which is early middle age for the fan but late senescence for a ballplayer. For most of his teammates, Perry is a figure from their childhood, when they watched the Game of the Week and traded bubble gum cards with his face on them. Jim Sundberg, his catcher, was seven years old when Perry signed with the San Francisco Giants in 1958, and shortstop Nelson Norman was not even born. Perry is the oldest active pitcher in either league. The only player of greater antiquity is his former teammate on the Giants, Willie McCovey.

This is the year Perry will begin to close in on two of baseball’s most celebrated milestones. At the end of last season he had 3141 career strikeouts, second to Walter Johnson’s 3508. It will take at least two seasons for Perry to surpass Johnson’s record, and by that time Houston’s Nolan Ryan may have set a new mark. However, with a good year—21 wins—Perry could win his 300th game, entering the Valhalla of big league pitchers where only fourteen immortals dwell. The last time he won 21 was in 1978, when he was 40. That was the year he won his second Cy Young award as the league’s best pitcher, making him the only man to accomplish that in both the American and the National leagues. But no matter how many records Perry breaks, he will be remembered as something else: the most famous outlaw in the game.

Crowd noise, which he identifies as a shuffling toward the rest rooms and concessions, tells Perry that the inning has changed, so he stands and folds his jacket in his usual precise manner, which is as exact for him as the correct way to fold a flag. Everything observable about Gaylord Perry can be described as a habit. The principal theorem of his science is to reduce the margin of error. As a result, he lives a queerly ascetic life, cleansed of variety and regulated to the point of fanaticism. He likes steak, he says, so he eats it at every meal, including breakfast, which differs from dinner by the accompaniment of an egg. He also likes spaghetti and country ham, but he will eat them no more than twice a year and only between the end of the season and New Year’s Day, when his training invariably begins. He is fond of Wente Brothers’ Le Blanc des Blancs, a cloying, fruity wine, and he drinks nothing else—except champagne whenever he wins a Cy Young award. In all of his married life he has never eaten a casserole. “The first year we were married I cooked a tuna casserole,” says his wife, Blanche. “He looked at it and said, ‘Where’s dinner?’ ”

“Perry has a habit of picking on victims who are unable to retaliate, such as batboys. He wrapped one helpless lad up in adhesive tape like a mummy and left him lying atop the lockers. He also comes up to his teammates and squeezes their injuries, asking, ‘That doesn’t hurt, does it?’ ”

Even his walk to the mound is choreographed. Rangers catcher Jim Sundberg noticed the invisible path after watching Perry cover first base at the end of an inning. “Instead of walking directly back to the dugout, Gaylord will walk back down the first base line to right about here,” says Sundberg, pointing to the imaginary intersection where Perry makes a ninety-degree turn back to his seat. It is a hint of the superstitiousness that enforces his rigid habits.

His moods, too, are routinized. “A couple of days before he’s scheduled to pitch he starts getting edgy,” says Blanche. “He’s hard to please. He yells a lot. It’s his way of getting mentally tough.” By the time he begins to pitch he is so unapproachably angry no one dares to smile in his presence. In any clubhouse there is a considerable amount of rough humor, but it is never directed at Perry. The players have learned better. Even his practical jokes follow a pattern. “You don’t mess with Gaylord,” says Bump Wills, the Rangers’ second baseman. “His paybacks are pretty vicious. Very vicious.”

Perry has a habit of picking on victims who are unable to retaliate, such as batboys. He wrapped one hapless lad up in adhesive tape—“like a mummy,” says Wills—and left him lying atop the lockers until another player discovered him. When Perry played for San Diego, spectators who draped their bare feet over the edge of the Padre dugout would suddenly find their toes frozen with ethyl chloride. “One thing I don’t appreciate is that he keeps hurting our own players,” says outfielder Richie Zisk. “He’s always coming up and squeezing their injuries and saying, ‘That doesn’t hurt, does it?’ ”

His bullying behavior seems almost like a bluff when one hears the avid testimony of his friends back home. “We ain’t got no big heroes down here in eastern North Carolina, except for Gaylord,” says Booger Scales, an insurance man in Greenville. “I know more than anybody else what he has done for his mom and dad—the new car, the new stove, the big farm, the money in the bank.” Whatever mask of toughness and cynicism he holds up to ballplayers and reporters, he doesn’t show it to the buck-toothed kids in their Little League uniforms, who find him a patient and unpatronizing source of advice. Perry seems drawn to their naiveté, a quality he cannot tolerate in grown-ups unless they have been given dispensation by nature or circumstance, such as Mattie Coletrain, an aged, blind black lady from Perry’s hometown. For nearly twenty years Mattie has heard herself greeted across the staticky airwaves by radio announcers whenever Perry is pitching—his own Mrs. Calabash.

Some pitchers, such as the Yankees’ Luis Tiant, like to bewilder batters by varying the windup or delivery with every pitch. Perry is the strictest opposite. Like an aspiring magician, he spent hours in front of a full-length mirror, eliminating quirks and unconscious gestures, training his hands to do nothing that was not stylized. He still reviews films of every performance, searching for any extraneous motion that might give away his intentions or weaken his delivery. Each Perry pitch is prefaced by the same routine: wiping his forehead with his thumb, back and forth, back and forth, pinching the bill of his cap, twice patting the graying hair behind his right ear, then back to the cap. These movements are as ritualized as the sign of the cross a Latin batter makes when he approaches the plate. Perry calls them decoy moves; he learned them by studying Don Drysdale and Lew Burdette, two pitchers who were also known for throwing the pitch that made Perry famous—the spitball.

Like the Frisbee and the theory of gravity, the spitter—or greaseball, as it is rightly called in its present incarnation—is a product of inspired accident. In 1902 an Eastern League outfielder named George Hildebrand was standing beside a rookie pitcher, watching him warm up. “He threw his slow ball by wetting the tips of his fingers,” Hildebrand later recalled. “Just as a joke, I took the ball and put a big daub of spit on it and threw it up to the catcher. The ball took such a peculiar shot that all three of us couldn’t help but notice.”

A few years after Hildebrand’s discovery, Big Ed Walsh of the White Sox won forty games with a spitter, which he made more lubricious with a chaw of slippery elm bark. The spitter was quickly attacked as “a disgusting and pernicious example to thousands of boys.” One of those boys was Burleigh Grimes, who when he was eleven saw a pitcher in St. Paul named Hank Gehring go to his face with his hands. “I asked my uncle what he was doing, and he said he was throwing a spitball,” says Grimes, now near ninety and a member of the Hall of Fame. “So I went home and got some bark and started to workin’ on it.” Ten years later Ol’ Stubblebeard, as he was known (like Perry, he would not shave between starts), was in the major leagues, where he pitched for nineteen seasons, becoming the most famous spitballer of his era and the last man to throw the pitch legally. The spitter was outlawed in 1920, but pitchers who relied on it were allowed to go on using it until the end of their careers.

The official reason for the ban on the spitter was that it was unsanitary. The real reason, as every batter knows, was that it was too hard to hit. The year before the spitter was made illegal, Babe Ruth hit 29 home runs, a record many said would never be broken. The next year he hit 54, and the fans broke down the gates to see him. Since then, rule changes have always favored the hitters: fences were brought in, the ball made livelier, the mound lowered, the strike zone shortened. “It’s a slap in the face of pitchers,” says Jim Kern, the Rangers’ reliever. “The rules committee forces a lot of pitchers to go underground.”

Burleigh Grimes threw the last legal spitter in 1934, four years before Perry was born, when he went nine with no decision against Carl Hubbell. By then, legal or not, the pitch was a part of the established repertoire of unscrupulous hurlers, not only in the big leagues but also in sandlots and cow pastures all over the country.

Perry’s father, Evan, was a sharecropper in the little hamlet of Farm Life, North Carolina. He threw knuckleballs for the local semipro team until he was 45 (he was noted for his endurance, once having pitched and won both ends of a doubleheader). His boys, Gaylord and Jim, grew up playing ball after church on Sunday, using balls they made with rocks and tape and rolled-up stockings, oak roots for bats, and fertilizer sacks for uniforms—an unimaginable distance in time and place from the day when they would each win a Cy Young award and become the most victorious brother combination in baseball history.

In a few years backslapping scouts were flocking to eastern North Carolina to sample Ruby Perry’s deep-dish pies and watch her boys pitch. Jim, the older, signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1956, when the scout for the Giants was already calling his kid brother “the best seventeen-year-old pitcher in the country.” Both Jim and Gaylord are big men; each is six four, although Gaylord has the bigger frame. When he came into the minors he had a rising fastball and a modest curve, not enough, he realized, to make the fine pitching staff of the San Francisco Giants. “I could see down the road that although I threw hard when I first came up, that wasn’t going to keep me in the game. Some of the guys on the Giants’ staff, like Don Larsen and Juan Marichal, threw really hard, and some of them were clever. I realized I needed a good off-speed pitch, a good slider, and a big motion. The motion is what deceives the hitter. I got mine from Juan Marichal. He used a big leg kick, and I could see how it hid the ball from the batters.”

While Perry worked on the slider, the Giants’ management was growing cool on the young pitcher, who by 1964 had four wins and seven losses in his two partial seasons with the club and an ERA of 4.38. They were about to send him back to the minors when the white knight of Perry’s life arrived in a trade with the Braves—Bob Shaw, whose name will live in baseball lore for two accomplishments: he beat Sandy Koufax 1–0 in the 1959 World Series, and he taught Gaylord Perry how to throw the spitter.

Prepare, pucker, and pop—the three P’s of the spitball,” says Shaw, the spitball evangelist, now a real estate developer in West Palm Beach, Florida. Shaw is a large, cheerful man with a facial resemblance to Archie Bunker. He claims to have taught the pitch to only two men, Perry and Tony Cloninger, “and right after I taught it to them, they each won twenty games.” Shaw learned it from Frank Shellenback, an old pitching coach for the Giants whose own career had been ruined when the White Sox failed to register him as a legal spitballer in 1920.

“First, you take your glove off and spit in your hand,” says Shaw. “Back when I pitched, you were allowed to go to your mouth, and I always chewed slippery elm lozenges, which made the spit very slimy. You prepare the ball by rubbing the slippery elm into the spot, which for me and Gaylord and most spitballers is in the wide part of the horseshoe just behind the seam. Lew Burdette used to throw it between the seams using regular spit, but that was very unusual.

“When you’ve got a good load on the ball, the next step is to pucker the fingers—by that I mean you have to force the ball in toward the palm, so that your knuckles are slightly puckered up, but not so high as with a knuckleball.

“Now the pop is the pop of the wrist when you throw it. Since there’s no friction on the top two fingers, it squeezes out just like a watermelon seed, with just enough drag from the thumb to give it a forward spin. With that rotation, the ball is bound to go down.”

What makes the spitter such a treacherous pitch to hit is that it is thrown as hard as a fastball, but it has the habit of dropping suddenly and precipitously just as the batter begins his swing. “It’s like a hard knuckleball,” says Yankees outfielder Reggie Jackson. “It’s the hardest pitch to hit.” Because of the slow rotation the ball appears to be coming in dead, or nearly so, tumbling forward in an indolent fashion and advertising itself as a regrettable mistake. The secret of the spitball is that it is meant to be swung at, but pitches that start out belt-high often drop well out of the strike zone before splashing into the catcher’s mitt. The hitter who is fortunate enough to make contact at all will usually hit the top of the ball and drive it into the ground, which is why the spitter is frequently thrown when a double play is needed.

Perry is not the only pitcher who relies on the spitter; he is merely the most notorious. All major league clubs have at least one spitballer, according to former umpire Tom Gorman, and some have two or three. And of course, the spitter is not the only illegal pitch. A scuffed ball is more common and sometimes more wicked; it rises or sinks depending on which side is scuffed. A curveball pitcher can enhance his curve with a bit of pine tar on the ends of his fingers, giving the ball extra spin. Dave Duncan, the former catcher now coaching the Indians, believes that half the major league pitchers are doing illegal things with the ball. “A pitcher will always keep one pitch in the back of his mind,” says California Angels pitcher Jim Barr, “one pitch that he won’t talk about. That’s the one he’ll save for the time when he really needs it.” Bill Lee of the Expos is the only confessed spitballer; others call their spitters by another name—most often the forkball, which is an honest but eccentric pitch that is much more difficult to throw. It behaves in a similar manner to the spitter in that it drops down, in a kind of swoon. The name comes from the ball’s being wedged between the two pitching fingers like a pea between the tines of a fork. At the moment of release the ball is poked out with the thumb in the same motion that a nurse uses to administer an injection. Perry, who likes to be coy on the subject, calls his spitter a “supersinker.”

Ever since the pitch was outlawed, libertarians in the game have lobbied to make it legit, with the result that the rules have become more and more strict but less and less enforced, like the liquor laws in Oklahoma. Even now, when umpires are supposed to have the authority to toss a crooked pitcher out of the game, they’ve been officially discouraged from doing so.

Perry threw his first spitter on May 31, 1964, when the Giants were playing the Mets in the longest game in baseball history—seven hours and 23 minutes, and that was the second game of the doubleheader. Altogether there were 32 innings of baseball, the most ever played in one day between major league teams. The first game started at one o’clock in the afternoon, and the second finished just before midnight. Perry didn’t make an appearance until the thirteenth inning of the second game. “Frankly, there was nobody else left,” he recalls. “And it wasn’t a case of saving the best for the last. I was the eleventh man on an eleven-man pitching staff.”

In the fifteenth inning Jim Hickman of the Mets led off with a single and moved to second on a sacrifice bunt. “We were in a position where Gaylord had to do something,” remembers Tom Haller, who was the Giants’ catcher in that game. “They had the winning run on second and one out and I knew we needed to keep the ball on the ground.” Haller called time and came out to the mound. “Gaylord,” he said, “it’s time to break the maiden.”

Perry recalls that his thoughts at that moment were of his wife and family, the old folks at home, his own inadequate salary, and the pertinent advice of his mentor, Bob Shaw: “There comes a time in a man’s life when he must decide what’s important. He must provide the best way he can for his family. You do that by winning in this game. That’s the only thing that counts—winning.” That day in Shea Stadium, when he went on to pitch ten scoreless innings, Perry learned that Shaw was right.

“There is an art even to cheating,” says Expos third baseman Larry Parrish, “and Gaylord is a true artist.” Cheating turned the marginal eleventh man on the Giants’ staff into the great pitcher he rapidly became. And yet the question that was to haunt his career from that day on was whether he could have made it on his own ability. He wouldn’t know the answer to that question for another ten years.

“I’ll be forever grateful to Haller, who put up with me that first season or two when I began wetting the ball,” Perry says. “I started out really slobbering on the old apple. Sometimes, I’m ashamed to admit, you could see the spray flying off the ball in flight.”

His friend Booger Scales remembers watching a game in Pittsburgh when the Giants were involved in a tight pennant race. “The score was two to two in the ninth, and Roberto Clemente was at the plate with a full count, when Gaylord struck him out with a spitter so loaded up that the spit got in your eyes in the stands. The Pittsburgh manager raised such hell he got thrown out of the game.”

In 1968 the rules were changed so that pitchers could not bring their fingers to the mouth inside the eighteen-foot pitching circle. The new rule occasioned what Perry likes to call “my struggle from spit to grease.” He had to learn to throw the ball with a lubricant, such as Vaseline, which he hid somewhere on his body or his uniform. Actually, it made him a better pitcher, since the grease gave him more control. That year he pitched his only no-hitter, beating Bob Gibson 1–0. Dick Dietz, his catcher in that game, says Perry threw only four pitches that were not greaseballs. “He had that stuff all over him,” Dietz says. “We didn’t have a sign for it, he just threw it. Curt Flood was the last batter of the game. Gaylord had him on a two-and-two count and threw him a greaser that Curt couldn’t have hit with a door.”

Managers who thought spitters had been banished were outraged by the greaseball, especially Whitey Herzog, who was managing the Rangers at the time. He took several balls he said Perry had thrown and sent them to the commissioner’s office for chemical analysis. Although it was never proved in the lab, Perry was not only using Vaseline but also experimenting with K-Y vaginal jelly. Ralph Houk, the former Yankees manager and an enthusiastic fly fisherman, suspected Perry of using fly-line cleaner, a waxy substance that is dry to the touch but beads when it mixes with water. Since each of these substances is nearly invisible when spread on the skin, finding the evidence is like searching for the purloined letter: it is always in plain sight. Complaining managers have inveigled umpires into examining Perry’s hair, his hat, his ears, his shoes—once he was made to change his pants. Managers who stand with their noses between Perry and the umpire are spellbound by the powerful odor that the pitcher exudes (it is often said that he smells like a pharmacy), and they can sometimes be seen sniffing about like a dog growing acquainted. Much-traveled manager Billy Martin once brought a bloodhound to the park and had the dog sniff through the ball bag. After the game, when reporters asked what had happened to the dog, Martin growled, “He died of a heart attack.”

The source of Perry’s bouquet is a fragrant analgesic balm called Capsolin. Players with aches and pains often use hot balms such as Deep Heat and Atomic Bomb to ease the discomfort; Capsolin is the black belt of these ointments. “Nobody else uses it,” says Rangers trainer Bill Zeigler. “It’s just too hot. The first time Perry was traded to Texas I got a call from the trainer in Cleveland. He said I was going to have to get some rubber gloves to rub the stuff on with. Once I accidentally got some on my nose and it raised a blister.”

Perry learned about Capsolin from Sandy Koufax, who used it to generalize the pain in his arthritic left elbow. Perry just uses it to keep his arm hot. When Jim Perry was Gaylord’s teammate in Cleveland he once made the mistake of borrowing a practice jersey. “All my shirts had gone out, and Gaylord had just got his back from the dry cleaner,” Jim recalls. “It was all clean so I put it on and went out running. In a little while I began to feel this incredible heat. I mean it was unbearable. My back was as red as a fire extinguisher.” Jim Sundberg has noticed that Perry’s shirts seldom last more than a few months. “That stuff burns holes right through them,” he says. Perry uses two tubes of Capsolin on his back and arm before every start and then refreshes his anointment with another tube in the fifth inning. “I think all his nerves are dead now,” says Zeigler. Capsolin, by the way, is a clear, greasy compound.

It is often said that Perry has never been caught, but it’s not true. He has been caught, but he has never been punished. Umpire Chris Pelekoudas found “a lubricant” on Perry’s right wrist in 1973, which was evidence enough to eject the pitcher from the game. But in the past Pelekoudas had been humiliated by league officials when he tried to call illegal pitches, so he simply made Perry towel off.

That same year Yankees outfielder Bobby Murcer got angry enough to say that baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn and American League president Joe Cronin “didn’t have the guts” to back up the umpires and eliminate the pitch from the game. Kuhn fined Murcer $250. Cronin mulled the matter over and surprised the world by concluding that Perry didn’t really throw a spitter after all. “Actually,” he declaimed, “all it really is is a hell of a sinker.”

Whitey Herzog had a bright idea. Perry was pitching for Cleveland at the time, so when the Indians came to Arlington, the Rangers manager ordered one of his pitchers, Jim Merritt, to throw spitters. Merritt was a worn-out left-hander with nothing to lose. He had never thrown an illegal pitch in his life, but that day he completely flummoxed the Indians’ batters, shutting them out 9-0 on a three-hitter. A fourth Cleveland player reached base when he hit a ball to third that was still wet when Jim Fregosi fielded it; he threw it fifteen feet over the first baseman’s head, into the reserved seats. Afterward, on television, Merritt confessed what he had done and was fined by the commissioner. Four days later Tigers manager Billy Martin tried the same trick. “We threw spitters, obvious spitters on purpose,” Martin said after the game. “This thing has got to come to a head. Somebody has got to take a stand.” Somebody did. The commissioner fined Martin and suspended him for three days, and before he could return to his club he was fired.

In 1974, just as it began to seem that there was an official conspiracy to protect Perry, the rules were changed to allow umpires to call a pitch a ball on the mere suspicion that it was illegal; the second time it happened, the pitcher was to be automatically ejected from the game. “There goes Gaylord’s value,” groaned his own manager, Ken Aspromonte, who was trying to trade him. Perry started the first game of the year for Cleveland on April 6 and lost. He didn’t lose again until July.

It was the greatest season of Perry’s career, his dry year. Although batters sneered, Perry claimed to have developed a forkball, and he actually held a private demonstration for senior umpires in the Fenway Park bullpen. “I told them I was trying to break the habit of going through the motions such as wiping my forehead,” said Perry, “and they said that would help.”

Three days later Perry beat the world champion Oakland A’s without a drop of grease. “I believe he’s a better pitcher without the spitter,” said Sal Bando, who was 0 for 4.

On June 17 Perry won his twelfth straight game, striking out nine White Sox batters, including Richie Allen four times. On June 28 he won his fourteenth, a three-hitter, which put the mediocre Indians into second place. It was also, incredibly, his fourteenth complete game.

The next week in Milwaukee Perry pitched in a gale. Two tornadoes touched down within ten miles of the park while the game was in progress, and the light poles in the stadium swayed like palms in a hurricane. In the fifth, with the Indians down by two runs and the terrified umpires ready to call the game, John Lowenstein hit a three-run homer into a 55-mph wind, and Gaylord won his fifteenth straight. The record in the American League for most consecutive victories was sixteen, held by Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Schoolboy Rowe, and Joe Wood. Perry would get his shot at that record against the Oakland A’s.

It rained all night and all the next day when we got to Oakland,” remembers Herb Score, who was broadcasting the game back to Cleveland. “I don’t think any of us thought the game was going to be played. The park was almost empty. That was at a time when Oakland was having trouble drawing fans anyway.” The Indians were now in first place, and they sat around the clubhouse during the rain delay playing cards and enjoying themselves—all except Perry, who sat on the dugout bench holding three new baseballs in his huge right hand and staring intently through the screen of rain. There was a tarpaulin covering the infield, but the outfield grass reminded one writer of the Pontine Marshes. After 22 minutes the weather abruptly cleared, and the umpires ordered play to begin.

Vida Blue, the A’s dazzling left-handed fastballer, did not allow a hit until the fifth, and by then Oakland was ahead on a two-run homer by Gene Tenace. There had been a traffic jam in the parking lot since the third, when people realized that the game was under way, and fans were still crowding into the steamy stadium.

Early in the contest Perry unveiled a pitch of his own invention that has since become a standard feature of his repertoire: the puffball. Most pitchers use the resin bag behind the mound to dry their hands, in order to get a better grip on the ball, and spitball pitchers sometimes go to the resin bag when they are pretending to dry their fingers. Perry’s puffball is a mocking counterpoint to the spitter in that it is the driest pitch imaginable. He gets his hand so coated with resin that when he throws the ball it appears to be bursting forth from a cloud of smoke. “They’re so surprised,” says Rangers catcher Sundberg, “that most of them take it for a strike.”

Sal Bando protested the puffball to the home plate umpire, which brought Aspromonte raging out of the Cleveland dugout. “What the hell?” the manager complained. “It’s like slop out there but they won’t let my guy use something to dry off his hands. The whole thing is uncalled for.” The strikeout of Bando was number 2199 in Perry’s career, putting him ahead of Grover Cleveland Alexander. In the seventh, a home run by catcher Dave Duncan put Perry ahead 3–2.

That day he struck out thirteen men, his season high. Sometimes when Perry is pitching he seems to cast a spell over opposing batters—they are drawn into the mental game of rhythm and placement that is characteristic of Perry’s art. Put simply, they can’t help but watch. Hitters who have faced him for years will come to the plate and seem to fall into a trance. Often the only one immune from the charm is some free-swinging rookie with no sense of aesthetics; in this game, it happened to be Claudell Washington, who was two games away from the minor leagues and had never had a big league hit—until he came to bat in the eighth and hit a Perry forkball for a triple. But Perry retired the side without surrendering the run.

In the bottom of the ninth Oakland’s Joe Rudi hit a long fly ball to right field, which under better conditions would have been the second out of the inning, one away from Perry’s victory. Charlie Spikes, slogging through the wet grass with his glove above his head, stepped into a mud puddle and dropped the ball, and Rudi was on third with a triple. He was replaced by a pinch runner, Herb Washington, one of baseball’s footnotes, who played two years in the major leagues and never came to bat. Washington’s single talent was that he could run the hundred-yard dash in 9.2 seconds. Gene Tenace brought him home with a shallow fly ball, tying the game.

Blue quickly retired the Indians in the tenth. Perry walked the first man he faced, and the next batter bunted the runner to second. It was exactly the same predicament Perry had been in ten years before, in Shea Stadium, when he threw his first outlaw pitch. The question that had preyed on him ever since that day had finally been answered. He had won fifteen straight games as an honest man; now he was one run away from holding hands with Walter Johnson and—who knows?—perhaps winning again and again, setting a record that would never be broken. Claudell Washington was at the plate. “He was standing right up on top of it,” Duncan remembers. In any other year . . . but Perry had made a vow not to throw the spitter, so he fed him a slider high and tight.

Afterward, Perry was overrun by joyous Oakland players rushing to congratulate Washington and carry him on their shoulders to the clubhouse. In a daze, Perry walked through their grinning faces and the whooping of the crowd. “The only thing I could think of was to get off the mound,” he said later. “It was all over.”

He would spend many nights wondering what would have happened if he had thrown a spitter to Claudell Washington. Finally, in the last game of the year, he threw the only spitter of the 1974 season to the Red Sox’ Tim McCarver, who promptly smashed it into right field—the same spot where Washington had hit his game-winning single.

Although Perry is the most durable pitcher since Warren Spahn—he once went twelve years without missing a start—his teams have always tried to sell their Perry stock before the market crashed. The Giants, who are notorious for making poor trades, swapped him in 1971 for Sudden Sam McDowell. The next year Perry won his first Cy Young award for Cleveland. One Bay area sportswriter still insists it was “the worst trade in San Francisco history,” a powerful indictment considering its competition: giveaways of premier sluggers Dave Kingman and George Foster and of two-time batting champion Bill Madlock.

Cleveland traded him in 1975 to Texas, where he won 42 games in two and a half seasons before going to the Padres. His first season in San Diego he won his second Cy Young award, and Rangers owner Brad Corbett called the trade “the worst mistake I ever made.” One of Corbett’s last acts as owner was to rectify his error after Perry, demanding to be traded to an organization closer to his North Carolina home, deserted the Padres team.

Perry has grown to love his reputation; he likes to advertise himself by grabbing a gob of Vaseline and shaking hands with umpires and opposing managers, by walking to the mound with a bucket of water, flaunting his crime, so that he enters that strange margin where crooks and clowns meet each other and become a kind of rascal hero. What others do slyly he does . . . well, slyly too, but with one side open so that the fans are in on the joke. For over sixteen years he has parodied the perfect game, and made us remember that cheaters win, and that winning is all we care about; but rather than condemn him, we tend to love him like we do the big-hearted whore and the winking politician.

And yet the Gaylord Perry who returns to the Rangers is not nearly the outlaw he used to be. Age has begun to tame him, and in the process it is turning him into that most intolerable creature, a fake criminal. He still prefaces every pitch with his decoy moves, but as he grows older he throws the spitter less and less frequently. It has to be thrown hard or it won’t drop, and Perry throws it only often enough to keep his reputation. It is still the pitch of preference when there are two strikes on the batter and a runner on base, and it is almost certain retaliation after he has given up an important hit. But there are games in which he may not throw it at all. Early in the season he beat the Red Sox 8–0, the 51st shutout of his career, and afterward he said he was legal the entire game. “The forkball was working well,” he said. The funny thing is that nobody believed him.

Larry Wright, a Dallas native, is the author of City Children, Country Summer, recently published by Scribner’s.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Arlington