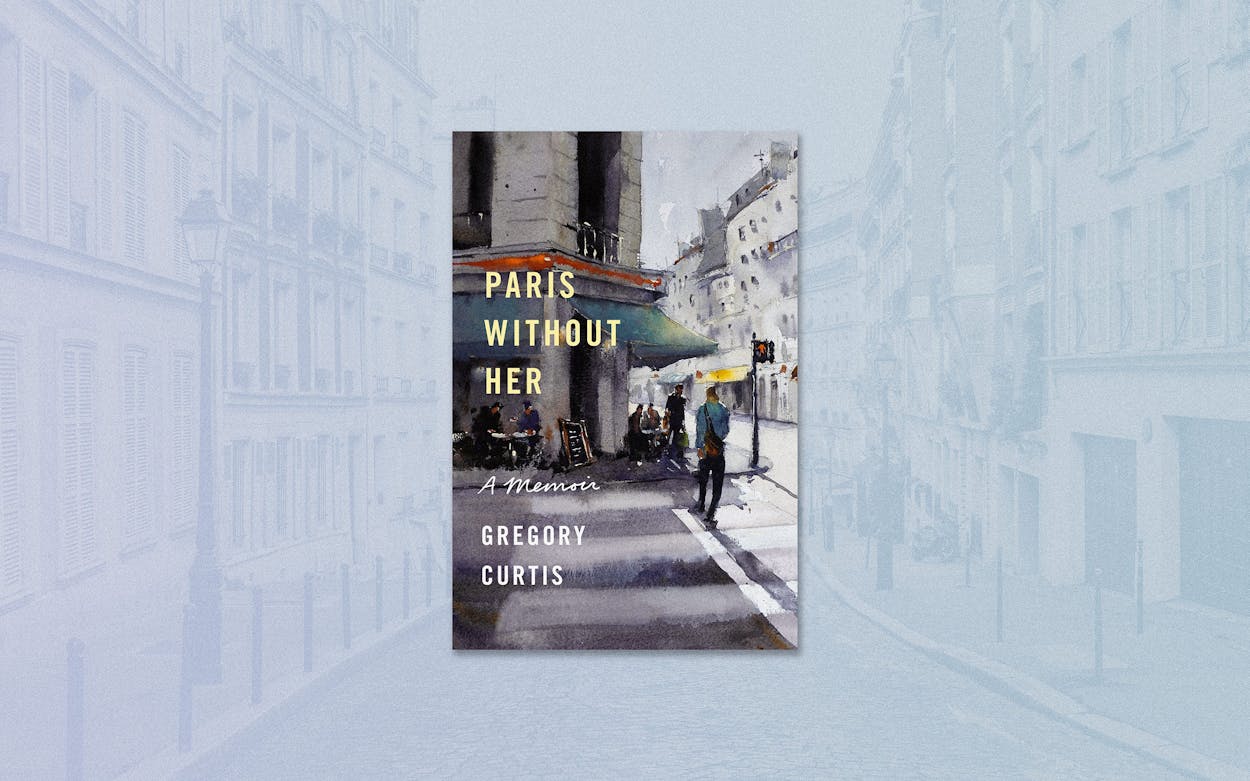

Though Greg Curtis has cast his attention overseas in recent years, writing books such as The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World’s First Artists and Disarmed: The Story of the Venus de Milo, Texas Monthly staffers and longtime readers know him best as this magazine’s editor in chief from 1981 to 2000. This was the role he occupied back in 1997, when I first met him and his wife, Tracy, who is the focus of Greg’s new book, Paris Without Her (Knopf, April 20). Part remembrance, part meditation, the memoir traces my former boss’s relationship with Tracy and his own journey after her death from pancreatic cancer in 2011, when she was 67.

Texas Monthly: One thing that struck me while reading Paris Without Her is that I’ve always thought of you as a private person. But this book is so revealing that I’m wondering if maybe I was wrong. Was your usual reticence an obstacle to writing this book? Or was it sort of liberating to expose so much of yourself in print, and in such detail?

Greg Curtis: I don’t know about liberating, but no, I wasn’t intimidated by that or, conversely, encouraged by that. I didn’t think, “Aha! Now I can get out of this suit!” It just wasn’t a factor, and it isn’t now. It is what it is; it is what I wanted it to be.

TM: Had you written anything else quite like this?

GC: No, other than some of the personal essays I wrote for Texas Monthly. I think if I look back, I’d be surprised at how many there are. But anything of this length, no. Not even remotely. I reveal things that if anyone had known to ask, I would have told them. There isn’t anything where I thought, “Oh, gee, if I say this, people will know this about me, and I don’t want that.” There just isn’t anything like that—I hope.

TM: When you were teaching me how to write a Texas Monthly story, you often said that you had a particular reader in your head. Was there somebody like that in mind while you were writing this book?

GC: There wasn’t somebody, but I felt I was writing to someone. It wasn’t anybody in particular; it wasn’t even male or female. It was just a reader. I wanted them to keep turning the pages; I wanted them to be interested. That’s always been important, but with a memoir it seemed even more important. Cave paintings or the Venus de Milo are interesting in and of themselves, whereas one’s life isn’t necessarily interesting.

TM: I was moved by the different ways you stayed connected to Tracy after she died. You wrote, “When I feel myself beginning to grin or opening my eyes slightly wider, I feel like Tracy and I are thinking the same thing at the same time, just as we did when we were sitting together.” Did you keep track of those sort of things as they were happening, or did you re-create those moments later?

GC: I would write these pretty long letters in the evening, and I would put photographs in them. And usually those letters were about where I had gone, what I’d done that day: “I went here, I did this, I thought that, I saw this; here’s a funny thing in a shop.” So I did have a record, so to speak. It wasn’t intended to be complete; I didn’t do it every day. But over the years that I was there, I had a pretty good diary of what I’d done and what I saw and what I felt, up to a point. And I did talk about how I’d often think that I saw Tracy, and then, of course, it wasn’t her. That would happen when I was walking, and then it would happen sometimes when I was just sitting and having a glass of wine or something.

TM: And Tracy wrote things down in your Michelin Guide.

GC: Yeah, she did. And she had a journal. I think she had more journals than I was able to find. I found the one for our last trip to Paris. I thought there were others, and I couldn’t find them. I don’t torture myself too much, but before I left at the end of 2018, I cleaned out my storage unit and gave it up so I wouldn’t have to pay while I was gone, and I’m worried that in the midst of throwing things out I threw some things out I shouldn’t have. But I don’t know.

TM: I think my favorite passage in the book is when you go into the Church of Saint-Eustache in Paris and feel an emptiness and understand that Tracy is somewhere in the emptiness. Did that type of thing ever occur to you in those big spaces before Tracy passed away?

GC: No, Tracy was more religious than I was or am. But after she died, in Paris I would sometimes find myself getting up and going to a mass on Sunday morning.

TM: Was that weird? Like, “What am I doing?”

GC: Yeah, I never do it here in Austin. I never go to mass or church. I might, but basically I don’t. Tracy and I had gone into churches in Paris and looked around. We did not ever go into Saint-Eustache. Nonetheless, I think I knew it was the kind of thing that she would have liked. I really liked it. It was a very high mass. There were seven priests and there was all sorts of to-do and the biggest organ in France, they say. So it was quite an event. And I was there, thinking about the great beyond and the great beings, and [Tracy’s presence] just came in without me even thinking about it. That was just part of the experience somehow. That wasn’t what I was there for. I don’t know what I was there for, except that I liked it.

TM: There’s this theme of reinventing yourself in another place that you touch on throughout. You wrote that at some point you may have felt “like an imposter myself, as if I simply disappeared from my former life and reappeared in Paris under the same name but as a different person who is leading a different life and does not have a past.” Even if you started out feeling like an imposter, I imagine you did eventually become a different person.

GC: Yeah, in some ways it’s true. You have to communicate in a different language, which in itself is a separation from your past and an invention of your future. I don’t feel like I was running from anything. But yeah, when I was there, that was one of the things that I kind of realized: that I’m different. I don’t have a past in Paris, really. Nobody knew who I was at all. Every now and then, someone would ask me about myself, like the grocer or the Algerian man across the street, which is very sweet, I thought.

TM: Is there a difference between you here and you there?

GC: Even though we were just talking about being a different person, I guess “no” is the answer because by now I feel really at home there. I know the places that I like, and I know areas I would like to go see that I haven’t. I feel very comfortable in Paris now. And I’ll note one little thing: I didn’t have a car, and I didn’t need a car. I didn’t want a car. If I went to the grocery store, I’d walk over—and not to one across the street. It was a very nice walk. Everything seemed to take less time and be less trouble because you could walk there. You didn’t have to get in, drive, park.

TM: That’s one of my favorite themes in the book: the wandering.

GC: The important thing is to walk without a goal. Often, you think, “Okay, I’m going to go to the Louvre today.” That’s a goal. But a lot of times I’d just walk out, see where things lead. You can’t let expectations get in the way of what actually occurs. You just take what comes and then make of it what you can. And you might find real joy. Sometimes I would give myself little things. For instance, on a street not far from my apartment, there were three or four bookstores on every block—used and rare bookstores. And so one day I went into every single one and tried to chat up the owner a little bit. Some were quite receptive, and some couldn’t be bothered. I looked at what books they had, and there were real differences because the books they had were the taste of the owner, to a degree. That was really fun. There were times when I made a little plan, so to speak. But more often than not, I just went.

- More About:

- Books