This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Moms are the heroes in my songs,” says Joe Scruggs, and therein lies the secret to his success. The parents with the purse strings have purchased nearly one million copies of Scruggs’s albums of children’s music, and the Austin-based singer and songwriter—a cross between Jim Croce, Jimmy Buffett, and Mister Rogers—plans to release his sixth album this year. A concert schedule that keeps Scruggs on the road two weekends a month further attests to the popularity of his music, in which Everymom evicts under-the-bed monsters, yields freezer space to preserve a snowman, and gamely attempts a ride on a birthday skateboard. Like “Fractured Fairy Tales,” Scruggs’s music works on two levels: Nonsensical lyrics and silly sound effects appeal to the kids; slice-of-life vignettes and sophisticated musical arrangements hook the adults.

Unlike the artificially bright Wee Sing series or the unremarkable Raffi, Scruggs makes music that is distinctively his. In his smooth, fluid voice he sings original novelty tunes, activity songs, parental love ballads, and updated nursery rhymes (his “Eensy Weensy Spider” goes waterskiing). Scruggs switches easily from rock and roll and pop to jazz to folk and bluegrass. His topics range from the mundane (“Refrigerator Picture”) to the fantastic (“Twilight Zone Home’’), from timeless subjects like first-day-of-school blues to the strictly eighties phenomenon of the malfunctioning computer-chip toy.

In “By the Way,” a boy interrupts the Monday morning rush to school and office with an apologetic “Oh, by the way, I need an orange juice can,/Four cotton balls, and/Six rubberbands,/And, by the way,/I’m an angel in the play./I’m gonna sing,/And I need some wings.” In “Take a Nap” a child grouses about his mother’s insistence that he rest, and the final verse reveals her true motive: She wants him to lie down so she can too—at which point a soprano chorus breaks in with a heartfelt “Hallelujah!”

Some songs educate (“Read a Book”), and others address childhood fears, like “Goo Goo Ga Ga,” which Scruggs pegs as the all-time favorite of his junior audience. In it he uses baby talk to offset the potentially scary voices of an overgrown alligator, a witch, and a troll. The lyrics may bog down in preachiness—as in “Pour on the Sugar,” an anti-spanking song—but Scruggs generally shies away from morality playing. “It puts a real damper on your creative flow ,” he says. “I try not to clobber kids with messages.”

Instead, he occasionally clobbers them with sentimentality, the bugaboo of children’s music. Scruggs readily admits, “It doesn’t take much to make me cry.” Sometimes he is right on target, as in “The Rocking Chair”: “Holding my little girl’s hand/She’s watching the ceiling fan/As we go rocking, rocking, rocking in the rocking chair”—a freeze-frame for any Texas parent who has watched the spinning blades lull a wide-eyed baby to sleep. But often he turns mushy, as in the breathily delivered “Grandmas and Grandpas.”

Scruggs also has a painful proclivity for false rhyme (like “squash” with “defrost”), and all five albums contain their share of cuts that are mediocre (“Raindrops and Lemon Drops”), predictable (“ABC”), or even annoying (“Are We There Yet?” is just as irksome set to music as it is queried en route by a traveling child). Many tunes have a singsong rhythm not unlike advertising jingles and circle endlessly in a grown-up’s brain (“The people in the car go up and down”). But by and large Scruggs wears well, and his wholesomeness—in the age of Pee-wee Herman, when children’s entertainment is growing ever more janglv and manic—can be a welcome change of tune.

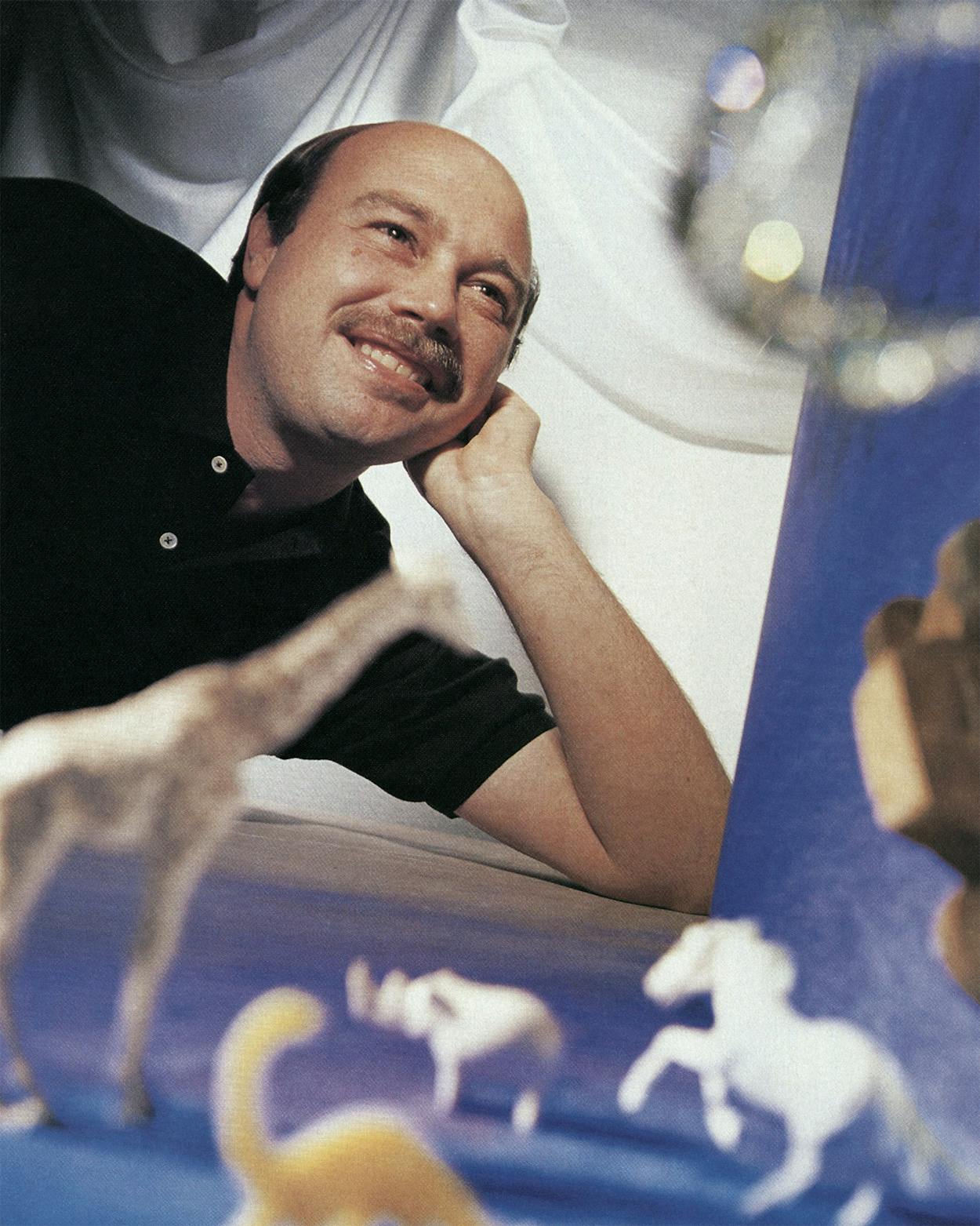

A born dad, the balding, baby-faced Scruggs, 37, was childless when he started his performing career (he and his wife, Linda, now have Patrick, five months, as well as big sister Casey, four). His El Paso upbringing helped fuel his mom-as-hero philosophy: “My dad was the typical dad of the fifties and sixties, and my mom always had to deal with it—whatever ‘it’ was.” After finishing a master’s degree in radio, TV, and film at Texas Tech, he moved to Austin and began working as a computer repairman for Radian (“I could put my brain in idle and let my subconscious work on songs”). His background is not particularly musical—he’s no relation to bluegrass great Earl Scruggs—but he habitually “played a little guitar and plunked out songs for my wife,” a kindergarten teacher. He penned parodies like “Bringing in the Sheets” to amuse her and her colleagues at teachers’ conferences. The funny stories that Linda brought home from school inspired his earliest children’s songs, like “Please Don’t Bring a Tyrannosaurus Rex to Show and Tell.”

Hearing them, Scruggs’s father offered to front the money to make an album. Pete Markham, a high school friend who also worked at Radian, volunteered to undertake marketing and distribution duties. So one day in 1984 Scruggs appeared, cassette in hand, at the Austin Recording Studio. There owner Wink Tyler called in freelance arranger and studio musician Gary Powell to score a four-song EP. Powell jazzed up Scruggs’s folksy delivery with overdubbed percussion and piano and sound effects like boinging springs and revving engines, then signed on backup talents like Austin flutist Megan Meisenbach and drummer John Treanor of Extreme Heat. The result further impressed the elder Scruggs to the tune of $20,000, and in September 1984 came a full-length LP, the sweet and bouncy Late Last Night.

On his albums Scruggs’s folksy delivery is jazzed up with sound effects like boinging springs and revving engines.

But retailers, Scruggs discovered, were uninterested in an individual album. They wanted not a gimmick but a steady product. So Scruggs teamed up with Powell and Markham again and in October 1985 released Traffic Jams, a collection of car songs like “Buckle Up” and “Speed Bump Blues.” Retailers perked up; the well-timed release enabled them to feed the booming yuppie-baby business. Scruggs and Markham then made an effort to distribute both albums through Discovery Toys, a California manufacturer that promotes in-home sales parties, à la Tupperware. After concerted persuasion, Discovery Toys agreed to give the albums a spin—and ordered 100,000 copies.

The latest release, Even Trolls Have Moms, was produced completely in Powell’s West Austin home studio, using elaborate synthesizing equipment. Because Powell also directs a University of Texas vocal group, he was able to draw on his students’ and colleagues’ voices for choruses and asides.

Tapes of their work are used in concerts to back up Scruggs’s lead vocals. Scruggs never just sings; the emphasis is on fun for both the big and little ones in the audiences. Early concerts featured props pilfered from his daughter’s closet, like a stuffed crocodile and monkey puppets; now high-tech doodads include a remote-control spider and exploding rockets. The rotund, impish Markham joins in wholeheartedly, donning overalls, a straw hat, and a huge inflatable guitar for “Rock and Roll MacDonald” and pulling the string on a Mattel See ‘N Say to produce the animal noises.

Scruggs expects his business to gross half a million dollars this year. He is busy on a new album, and his 1989 spring concert schedule includes Indianapolis, Seattle, Little Rock, and six Texas cities. He spends free time with his family or listening to his favorite records—Brian Hyland’s “Itsv Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” and Smetana’s “The Moldau.” Life is good for Joe Scruggs; perhaps that’s why he has resisted overtures from the East and West coasts to relocate. Austin, like his music, is familiar and easygoing compared with high-powered big-city life. Yet in the scrubbed pastel world of Joe Scruggs, what is scary is not the unknown but the known—the realization that childhood will not last, that children will grow up and, as a new song puts it, grow away. Time is inexorable. And there are darker things—Scruggs knows of at least three children’s funerals at which his music was played. Whispers one chorus: “Yes, I know where angels sleep.”

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Austin