John Wooten’s specialty in football has been creating holes on the field and helping his teammates blaze trails off it. In the nine seasons that the East Texas native played guard for the Cleveland Browns (1959–67), a Browns running back led the NFL in rushing seven times (six of those rushing titles belong to Jim Brown; Leroy Kelly won the other). Wooten grew up in Carlsbad, New Mexico, and first played organized football as a high school sophomore, after the city’s schools desegregated. In 1955, Wooten became the second Black football player at the University of Colorado. When high-profile Black athletes began to make their voices heard in the late sixties, Wooten became a powerful civil rights advocate alongside the likes of Muhammad Ali; Bill Russell; Wooten’s teammate, Brown; and several others. Their “Cleveland Summit,” which concluded with the players’ public support of Ali’s position as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, took place 54 years ago this week. In July 1968, Wooten was placed on waivers by the Browns after he publicly expressed displeasure with Black players being excluded from an offseason team golf outing.

His subsequent work in NFL front offices included top-level scouting positions with the Dallas Cowboys (1975–91), Philadelphia Eagles (1992–96), and Baltimore Ravens (1997–2003). In 2003, he cofounded the Fritz Pollard Alliance, which pushed the NFL to adopt the Rooney Rule to increase opportunities for non-white candidates to land head coaching and front-office positions. Wooten retired from the Fritz Pollard Alliance in 2019, and now the 84-year-old stands on the figurative sidelines, observing social activism among today’s athletes from his home in south Arlington. He spoke with Texas Monthly last month.

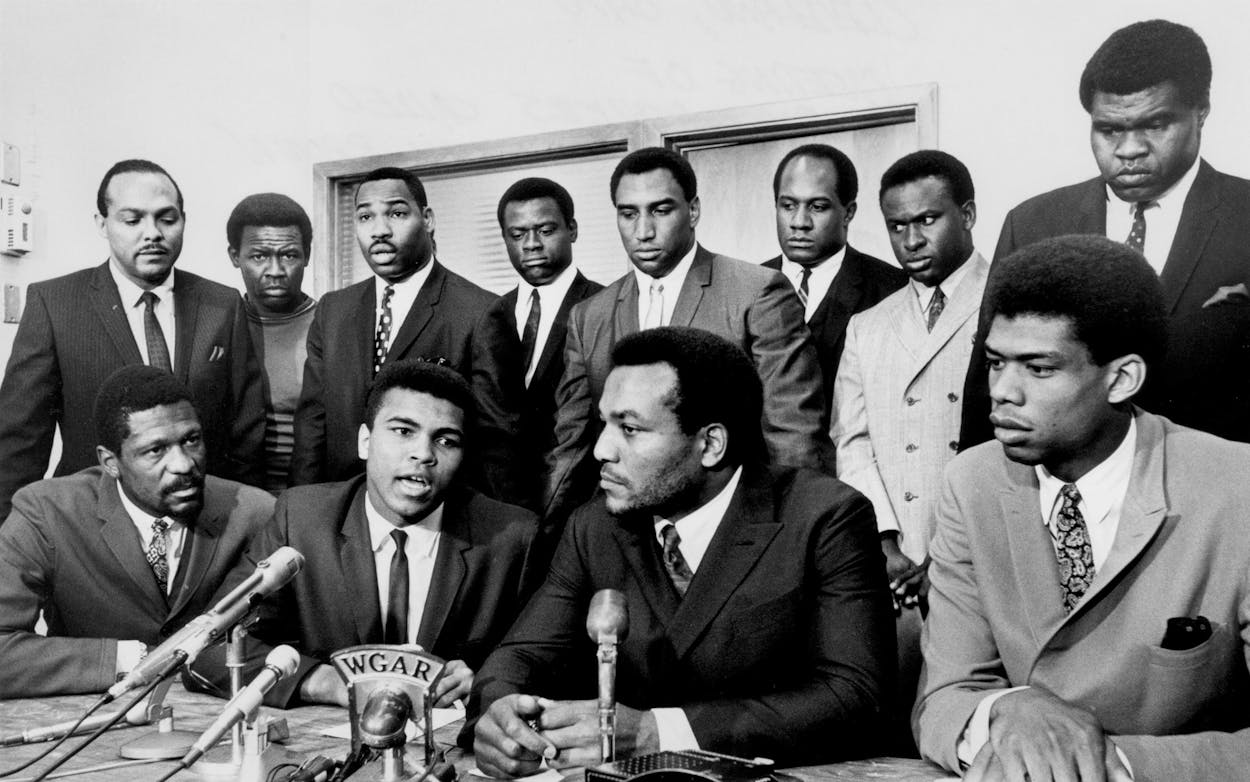

Texas Monthly: The 1967 “Cleveland Summit” included you, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Bill Russell, fellow football standouts Willie Davis, Bobby Mitchell, and Curtis McClinton, as well as Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), who was then playing at UCLA. What was the purpose of that gathering?

John Wooten: Jim and I, under Jim’s creation, had put together an organization called the Negro Industrial Economic Union. Knowing that we were athletes, I set up a meeting with Dr. [Martin Luther] King, and I said to him, “Dr. King, as much as we support what you’re doing, it is very difficult for us as athletes to march with you, to sit in at the sit-ins or the demonstrations, so forth, because we as a group would have trouble with letting people pour syrup and spit on us and all that kind of stuff and not respond. But we support what you do. What we’re going to do is create this organization to help build economically in communities around the country. And that organization was funded by the Department of Commerce under the EDA, Economic Development Administration, to work with, to try to build an economic base. And this organization allowed us to raise money so that we could use it as seed money to help establish shops, barbershops, shoe shops, drugstores, all kind of different businesses within the Black community around the country.

Jim and all of us met and got to know the Champ [Ali]. That’s what we called him—the Champ. In ’67, the Champ does not step forward in Houston [reporting to the U.S. military induction center]. What they were planning to do is declare the Champ a draft dodger and put him in jail. They immediately took away his crown. They immediately took away his passport. So, Herbert Muhammad [Ali’s manager and son of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam] calls Jim and says, “We need your guys’ help.” Jim is living in L.A., calls me and says, “Herbert Muhammad just called me. Get the guys together. We’ll meet on Saturday in Cleveland.” So, everybody was talking to [Ali] about [how] he could go in a special service. [Ali said,] “I don’t want to be associated with any organization that kills people. And that’s what the U.S. military does—kills people. I’m not going to be . . . I don’t want to be associated with it.” When it was all over, we stood with him to say you are a conscientious objector and therefore you should not have to go to the military. And later on [in June 1971], the Supreme Court said exactly that.

TM: As we speak on May 25, it’s the anniversary of George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis. How would you say pro athletes have responded?

JW: I have been overwhelmingly joyful, and it goes all the way back to when the [NFL] commissioner [Roger Goodell] announced early on that the league itself was wrong in standing against the kneeling and the openness to which the players had shown two years ago, going all the way back to [Colin] Kaepernick. . . . The players were fighting for equal justice, justice equity. We’ve always fought for the right to do what you have to do under, number one, the law of God, and the law of this land. The Declaration of Independence was not written to protect us as minorities, people of color. But what they did say was that all men were equal under God, and that’s where the rights come in . . . that’s what you’ve got to hold them to. This is the kind of thing that we’re fighting. But by the same token, we recognize that this is still the greatest country in the world as it relates to who we are and where we are as people. [There’s] nowhere else, I truly believe, that you and I would be having this kind of conversation.

TM: Why do you think some white fans don’t understand or accept the social causes that Black athletes have stood for?

JW: I can’t tell you the number of times that I’ve been stopped for no reason other than “driving while Black.” When I went to work for the Philadelphia Eagles in ’92, I’m working there as the vice president of player personnel. In preparation for the draft, you’re working late in the office. My wife had been wanting to go see this movie. I said, “There’s a late movie at 10:30. I promise you’ll I’ll be home, and I’ll take you to the movies.” Movie’s out about 12, 12:15, and we’re driving home. And I live in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, just across the bridge from Philadelphia. We’re driving, and I notice this police car pulled up right behind us. I know they’re there and don’t understand why he’s there, ’cause number one, I’m not speeding.

So I keep driving. Now we get to where I need to turn in to go to the condo where we were living. All of a sudden, he puts his lights on, flashing and blinking. So I stopped and he . . . I’m looking in the sideview mirror. And I notice as he gets out of the car, he unsnaps his pistol. My wife is just scared to death. So, he comes up, and I let the window down. I’ve my both hands on the wheel, okay? I know the procedure. And he says, “Where are you going?” I said, “I’m going home, sir.” He said, “Well, why did you turn up in here if you’re going home?” I said, “Because I live in that condo right over there to your left. That’s where I live.” So, he says, “Who are you?” I said, “My name is John Wooten, and I work for the Philadelphia Eagles.” So, he goes back to his car. He comes back, he says, “Why do you have Texas license [plates]?” I said, “I just took the job here with the Philadelphia Eagles. I’m from Dallas, Texas.” “Well, you get that changed, you hear?” I said, “Yes, sir.” That’s what I’m talking about.

TM: What were the circumstances of your departure from the Browns in the summer of ’68, after you’d started almost every game for the past eight years?

JW: [Veteran Browns cornerback] Ross Fichtner—we had been playing [in a golf event] down in the Ashland Country Club, where he was a member. We’d been playing down there like, it had to be like the third year. The year before, I had won. I have the trophy here now! And he calls and said, “I’m not going to invite any colored guys down this year to the tournament.”

I said, “What do you mean by that?” He said, “Well, the pro says last year some of the guys took items and didn’t pay for them.” I said, “Ross, you know, we know who was at the tournament. So, all we’ve got to do is go back, you and I, and get the money from each one of those guys—whatever the pro said they took—and pay him his money.” He said, “I don’t want to do that.” I said, “If that’s what you’re going to stand on, then I must take a stand because I’m not going to be a part of that. And I’m going to say that openly, that you’re wrong to do this. We’re all Cleveland Brown players, so it’s not hard to identify who the pro is talking about, right?” I called the Cleveland Press, Bob August, and I said to him, “Ross is having a tournament there in Ashland, which I won last year, and he’s not inviting us simply because, quote, we’re Black guys, and I’m against that.” Well, Bob August wrote it just that way in the Cleveland Press. [Browns owner Art] Modell’s reaction was he waived both of us. I’m a troublemaker; I’m gone.

It was obvious they were thinking I’m going to end up out of the league. So I said to the commissioner [Pete Rozelle], “I’m not going to let someone do that to me. I’ve done nothing wrong. I’m not the one who created this situation. Got to resolve it.” If I wasn’t on a team by X date, then I’ll be heading to the court to sue the league. And that’s when Edward Bennett Williams with the Washington football club stepped in and said, “Hey, I want ‘Woot’ to come here with us.”

The same Modell called me back when I was with the Eagles in ’95 and says to me, “I want you to come join us here at Baltimore and help us win a championship.” And he told me, “You were right for what you did in ’67. I was wrong.”

TM: During your time with the Fritz Pollard Alliance, how were you involved with Kaepernick and his protest against police brutality?

JW: I went to his agents, his representatives, and I said, “Let me talk to Colin. And if he agrees, I’ll have people—Jim Brown, Paul Warfield, Leroy Kelly, Cris Carter, Ray Lewis—I’ll have people that will stand behind him just as we did Ali.” And they came back and said Colin doesn’t want to do that. “I don’t have any more to say. I’ve offered to help.” I felt he needed to tell the American public that he wasn’t against the American flag, that he was not against the military, that he was against the injustice that he’s seen in this country as it relates to people of color. And that’s why he was kneeling. I think if he had said that just that way to the American public, I think the situation would have been different.

TM: All those years ago, what made you step outside the comfort zone of professional sports to become socially active?

JW: I grew up with a single parent, youngest of six. My mom taught me this: you stand for what you know is right, no matter who it is, what it is. Consequently, when I see wrong being perpetuated simply because of the color of your skin, I have no choice but to fight.

This conversation as been edited for length and clarity.