Whether it’s a grandmother’s rolling pin or a beloved Eagle Scout medal, we all have treasured objects—but they often sit unused in a drawer or gather dust on a shelf. In What We Keep, released September 25, writers Bill Shapiro and Naomi Wax bring together the stories of those objects from 150 people.

The idea came to them when Wax found an old, burnished locket at a yard sale in upstate New York. “It struck us: How did this thing that meant so much to someone at one time go from being a cherished possession to being in a box at a yard sale?” says Shapiro. “That got us thinking about the stories that get wrapped around these objects, and how over time, as they’re passed down, the stories start to fray and disappear.”

Over the next three years, Shapiro and Wax crossed the country, speaking with hundreds of people from all fifty states about their most meaningful possession. The items and the lives of the participants vary widely: Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban chose his 14 1/2-pound 2011 NBA trophy; activist DeRay Mckesson chose his signature blue vest; Art Williams, a bank note counterfeiter, chose his paintbrush. “It was surprising, but nobody chose an object with inherent value,” says Shapiro. “They were all matters of the heart.”

Many participants’ choices reflected a period of optimism and change, like that of Tim O’Brien, Austinite and author of The Things They Carried. He selected a Boston Red Sox cap that he started wearing right after returning from fighting in Vietnam. “It reminds me of a time in my life, a time of energy and possibilities, when things hadn’t narrowed,” he says in his entry. “When I look at the hat, it’s reminiscent of the feelings I had then, feelings of rebirth, I’m not dead and What am I going to do with this life that I didn’t expect to have?”

O’Brien is one of several Texans featured in the book. Below are three of the items, and entries, from the state.

Casey Gerald

author, There Will Be No Miracles Here, Austin

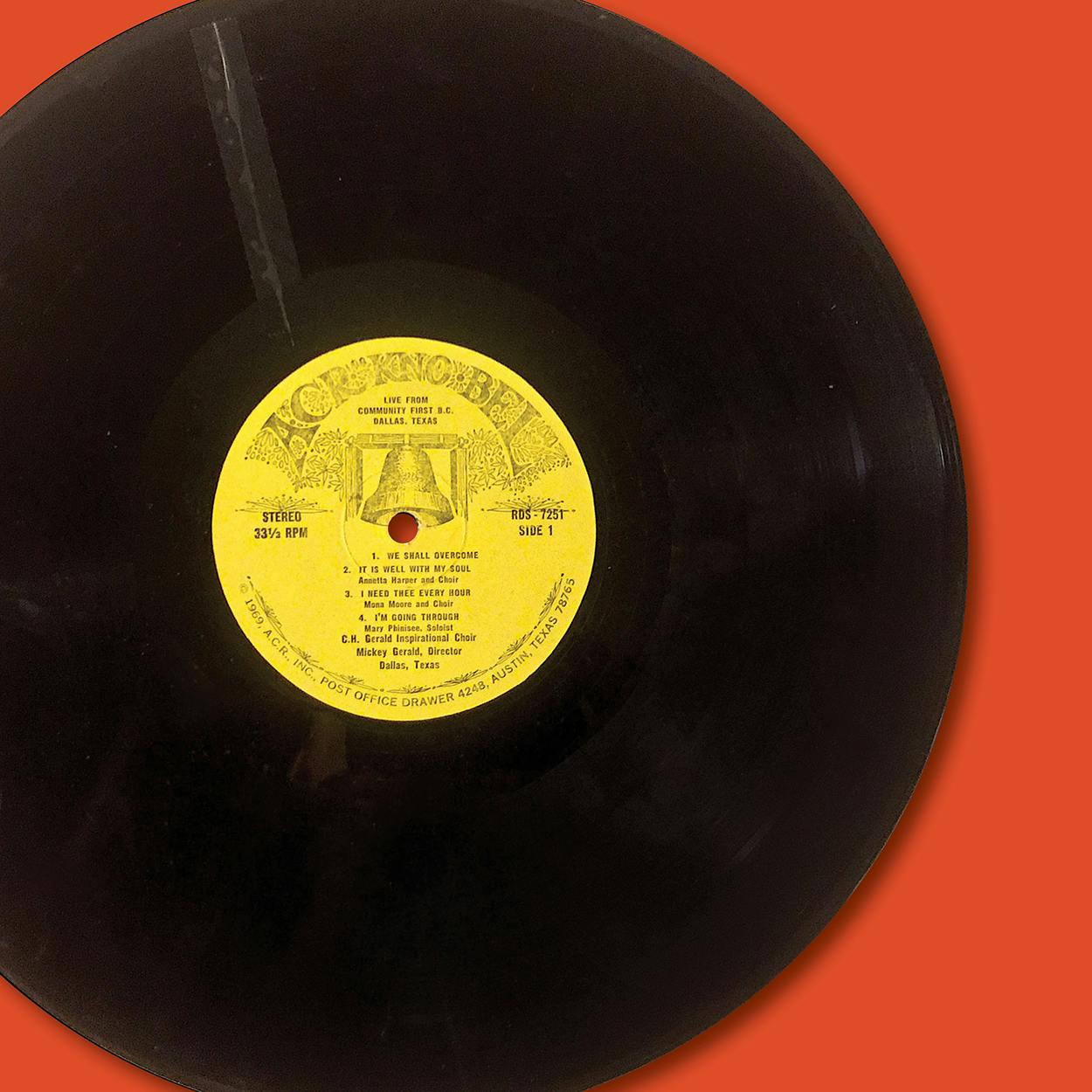

I have a vinyl record from 1969 of a sermon my grandfather gave when he returned to Bastrop, Texas, where he was born. He was born in 1928 and back then most of the black folks there, including my grandfather, were descendants of slaves. He began preaching when he was 16 or 17, and when he first started he got paid in canned goods, but he went on to start what became one of the largest churches in the black community in Dallas, at least before megachurches.

I found the record in my grandmother’s closet in 2012, when I was in business school. Her closet was this great archive: She hoarded all these old press clippings and church programs and photos—there were cassettes, but I’d never seen any vinyl.

I’ve got 30 cousins, so there’s a lot of clamoring for things, but I just said, “Hey, Granny, can I take this?” She as in a good mood that day, I suppose, because she gave it to me.

The album cover is fuchsia, which is strange, and it has white lettering that says “Community First Baptist Church, Dallas, Texas,” which is the church he founded. The choir—the C.H. Gerald Inspirational Choir—is named after my grandfather, and in a great case of nepotism, the director is his second-oldest son. On the B-side, the name of the sermon is “A Crown in Lay-Away”—my grandfather was known for his weird sermon titles.

We always had to go to church, but I don’t really remember hearing my grandfather preach in person. I remember more just hanging out with him. He’d take my cousin and me—we were, like, seven, eight, nine years old—to IHOP, and then after IHOP he’d take us to the Dollar Store and get us these cap guns, and he would always tell us about fighting in the war in Korea and about shooting people. We knew that in the imagination of a lot of people in the black community in Dallas, he was a huge, larger-than-life figure. But for us, he was this guy who was really cool—and who you were deathly afraid of.

For such a long time, it was illegal for black people in this country to read and write, so the black experience in America is largely an oral experience. And a lot of that came through the church, came through religion. So to have this recording of my grandfather at 41, at what became a sort of very prominent church that he had founded, and in the town where his family had lived all the way back to slavery, is incredibly moving.

Ellen Ochoa

Director, Johnson Space Center; first Hispanic woman to go to space; Houston

You don’t get to take very much on the Shuttle, so I was really happy that I was allowed to bring my flute. I starting playing when I was about 10, and I got this particular flute just before graduating high school. So it’s been with me for a long time, through band, ensemble, symphony orchestra, and solo recitals.

Space is obviously a place where I never dreamed I’d get to play it—184 miles above the Earth. Being an astronaut is what I’ve dedicated my life to, but music has always been there for me. The opportunity to play this flute in space brought all the parts of my life together and that was incredibly special. I played a Mozart concerto; sometimes when I play it now, I think back on that day.

Nat Rosenthal

Consulting executive, Houston

We did okay through the first days of Hurricane Harvey, through the rain. We fought it. But then they released the reservoirs, and it took us a while to realize that this was really happening. We fought that night, too, but at one point it was over: It came in all at once, from all sides of the house. Outside, it was dead quiet. No rain. No cars. The power was out. There was no movement. But the water’s coming in through the walls, through every crack.

That night I got a text from my son:

– How are you doing?

– Fine.

– Are the Magic cards safe?

Yes, the Magic cards were safe. They were the first things I’d grabbed from the office downstairs. My whole life was about to get flooded—there were photo albums, rugs, books down there—but I’d gathered the cards from the floor and brought them upstairs. It took four trips because there are 3,000 or 4,000 of them, in three-ring binders and 2-foot-long recipe boxes. My son was half-kidding—but only half. He wanted to know. Those cards are our connection.

I started playing Magic: The Gathering with a few guys in ’95 when I was studying for my MBA and getting sober. We stopped playing after a few years, but I kept my cards, kept them through my first marriage, and when I got divorced I brought them with me. I remember thinking, “Maybe my son will be a little nerdy, too, and I’ll get to share this with him.” When he was young, he liked the pictures. But as he got older, he liked that each game had an infinite number of possibilities. Being a divorced dad, I saw Ethan every other weekend and I was looking for ways to connect with him. On Friday nights, we’d go to gaming shops with names like Asgard, and they’d have tournaments. We’d get clobbered but we didn’t care—I was spending time with Ethan.

A lot of those cards they don’t make anymore and they’re worth quite a bit. But I keep them because my son likes them, because we have that connection.

- More About:

- Books