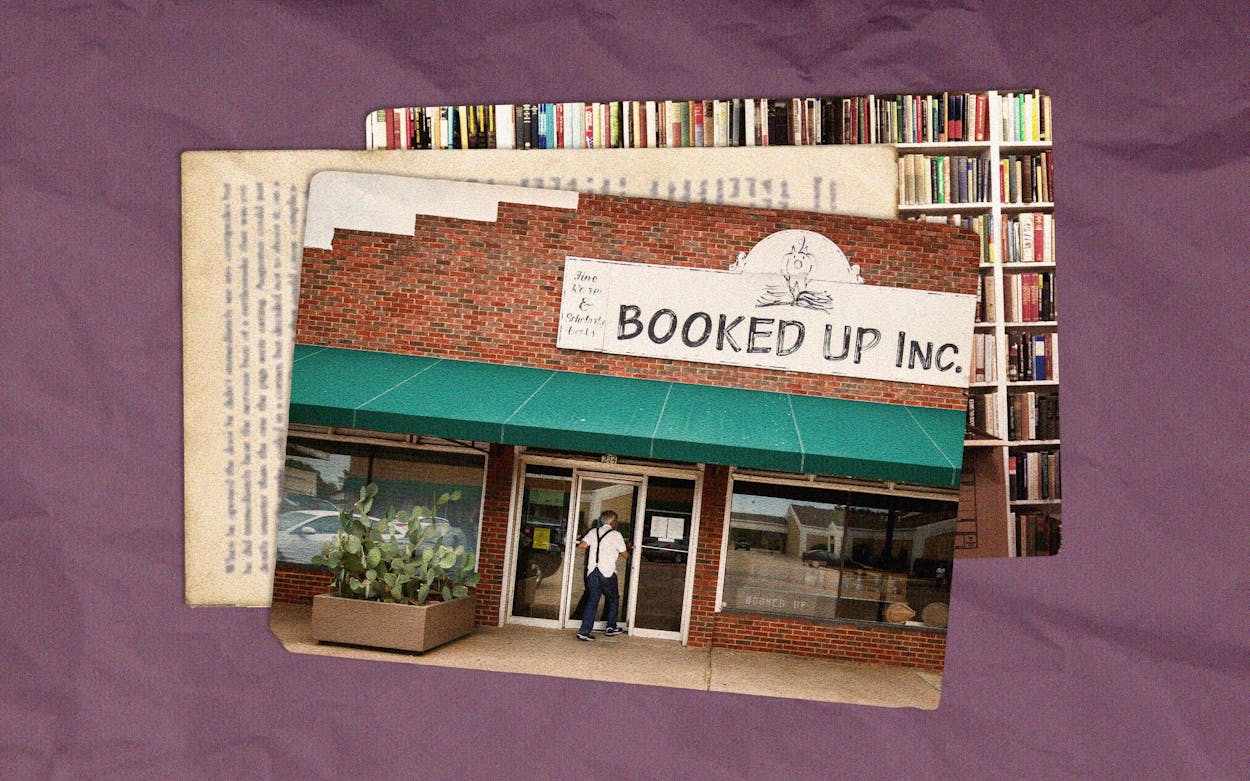

By 2002, when I first visited Larry McMurtry’s enormous bookstore, Booked Up, it was already legend. Its used, rare, and collectible books took up 30 percent of Archer City’s 66,518-square-feet of commercial space with rows upon rows of shelves. You couldn’t miss it. As an added attraction, I was told, the Pulitzer winner was often spotted working there, unboxing new acquisitions, weeding out any junk reads, and writing prices on the top right-hand corner of the first blank page in light pencil.

Since I was driving down Highway 281 from Wichita Falls to Brownsville for a story for this magazine, I would be skirting right past it. Archer City, then, was where I’d spend the first night of my drive. While I did love the smell of fresh-cut paper that hit me whenever I walked inside new bookstores, the musty smell of used bookstores held deeper memories of a childhood puttering around libraries. It was there that I formed my idea of the ideal book room: tall stacks where you can find interesting, weird stuff.

Booked Up exceeded my expectations. Driving up to the town square, I realized Booked Up had opened its doors in not one but multiple storefronts. For hours, I bounced from one building to the other, winding through the sections on twentieth-century English and American fiction, biographies, Western Americana, rare books, and poetry. I finally selected the out-of-print 1932 volume of The Circus From Rome to Ringling, by Earl Chapin May, that held the colorful, well-documented history I wanted for a story I was writing on circuses. It was 25 bucks—not bad for a book I’d never find anywhere else.

Once I’d checked in at the Lonesome Dove Inn, a sprawling house with bedrooms for visitors, another guest I’d met must have mentioned the arrival of a Texas Monthly writer to McMurtry, because in the late afternoon, McMurtry knocked on my door and asked me to go out to dinner with them. Of course, I said yes. Upon learning that I was driving a road and writing about it—something he had just done in his great book Roads—he talked, on the way to the restaurant, about travel literature, a genre he collected for his personal library to the tune of three thousand books. Many of the authors whose works he’d acquired were women travel writers whose high adventures included riding a dogsled off to a leper colony and roughing it in the Canadian bush. I was only driving six hundred miles via state highway by car; nonetheless he strongly recommended Eric Newby’s Slowly Down the Ganges. Absorbing that or any great travel story, he implied, would change how I’d see even a well-worn path. He seemed to have at least one book recommendation on any topic, though without much pressing, he could probably give ten off the top of his head.

“Book selling was mainly a way to finance my reading,” he wrote in his 2008 memoir about book-dealing, Books. While he started out as a book scout in Houston, acquiring inventory for the Bookman, it wasn’t until 1971 that he opened Booked Up, with his friend Marcia Carter, in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C., and by the mid-seventies, he seemed to get more of a thrill out of the store than the typewriter. “I began to view myself as essentially a bookseller—or maybe just a book scout,” he wrote. “The hunt for books was what absorbed me most. Writing was my vocation, but I had written a lot, and it wasn’t exactly a passion.” Writers, he suggested, get worse with age; booksellers, on the other hand, get better.

Eventually, with rent skyrocketing and book stock ballooning, Georgetown was no longer the best location, so he moved all 300,000 volumes in Booked Up to a place where he knew rent would be affordable: his own hometown, Archer City, population 1,500. It was there that he created his own version of a book town, with inspiration from Hay-on-Wye, in Wales, where more than thirty bookstores grace a city of 2,000.

In Archer City, the inventory grew further still, and he claimed to have gleaned at least a few pages of each of the 450,000 volumes that eventually graced the shelves. (For comparison, the typical Barnes & Noble stocks between 60,000 and 200,000 books.) As a reader and a dealer, his enthusiasm ranged wide, whether the book was Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, Goya’s Los Desastres de la Guerra, or a French book on an early trans-Saharan auto rally (“it’s a wonderful book, but it isn’t modern literature”). After a few decades in the business, he even started seeing some books from his personal collection, which he’d sold over the years, come back into his possession. Some pristine paperbacks he once sold to this magazine’s former editor Gregory Curtis wound up in a stash he bought from Wichita Falls. About sixty books he’d inscribed with his name and sold to book dealers, who tried to sand the then unknown writer’s name off the interior pages, landed back in Booked Up—more valuable with McMurtry’s fame, and a story, attached.

Over time, he noticed that the internet was disrupting the rare book trade, and the downturn in the economy in 2001 diminished the number of tourists beating the path to his store. Stranger still, he began to notice that “what consumers want now is information, and information increasingly comes from computers. That’s a preference I can’t grasp, much less share.” He hung on until 2012, when he sold off, at auction, 300,000 volumes. The shop eventually shrunk down to two storefronts.

Upon his death, in 2021, he left the store to his longtime work partner Khristal Merklin, who sold the buildings and remaining inventory but kept the name Booked Up for an online store of rare books about everything from art to western fiction. And the buyer of the storefronts and inventory? Magnolia’s Chip Gaines, who spent summers in Archer City, bought them, and though nosy types all over town (along with this reporter) have asked repeatedly, the current plans for reopening remain under wraps. To be fair, he has a few books to assess.

- More About:

- Books

- Indie Bookstore Week

- Archer City