One of the greatest events in the history of Conroe, located about forty miles north of Houston, happened 66 years ago, on August 24, 1955. On that night, Elvis Presley and other musicians from Shreveport’s Louisiana Hayride country music radio show performed for the town at David Crockett High School’s football stadium.

The twenty-year-old “hillbilly cat” from Mississippi was already a regional phenom when he drove into the roughly eight-thousand-person railroad town. National stardom would come months later with his release of “Heartbreak Hotel,” but for that one night, Elvis was Conroe’s alone to enjoy. To this day, the account of Elvis’s visit continues to be told and retold, every detail studied like a favorite drawing. One notable resident was even remembered more for his relation to that day than his lifetime of achievements: a story in the local newspaper commemorating the late Lee Meredith, a World War II veteran, radio deejay, and schoolteacher, ran with the headline, “Multi-talented musician, newsman had a hand in bringing Elvis to Conroe.”

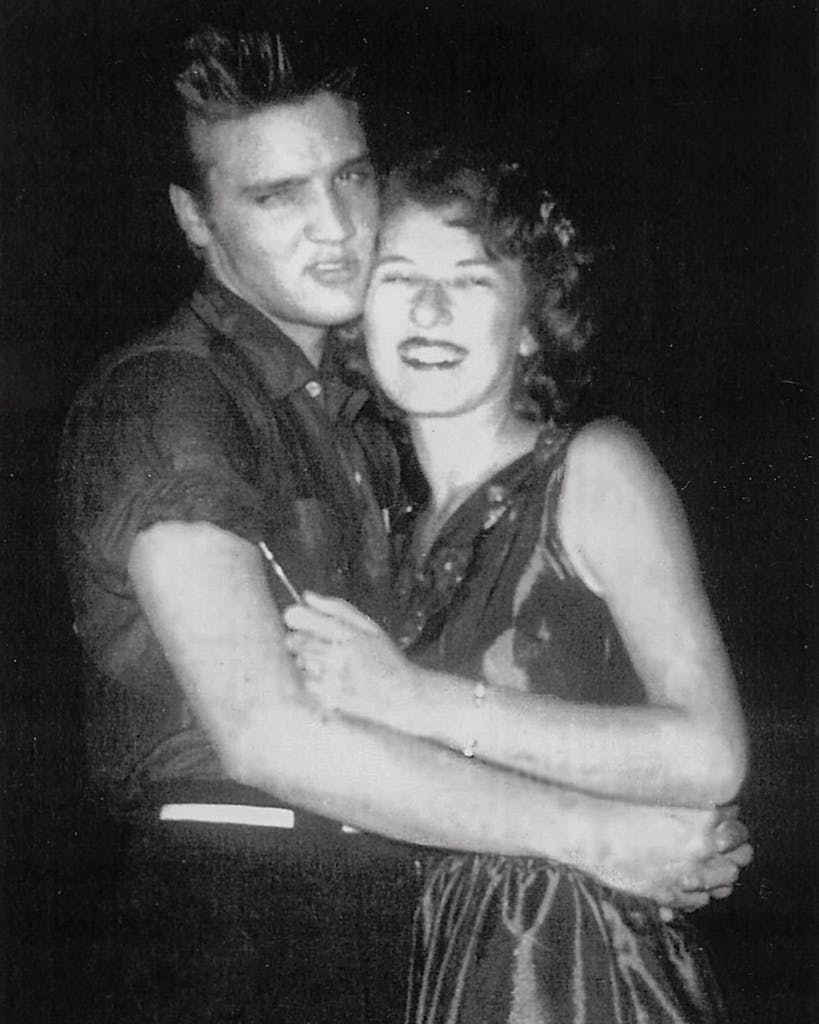

Photographs of Elvis’s performance quickly became cultural totems for the town. One image shows him and his band atop a makeshift stage (made from the beds of two pickups parked on the fifty-yard line of the football field). Elvis’s left hand is awkwardly over his shoulder and fiddling with his guitar strap, and the microphone obscures his face. But another photo shows his mouth twisted in a hunky sort of snarl while his arms are wrapped around the waist of a Conroe teenager named Mary McCoy.

McCoy wasn’t just another beaming fan. The sixteen-year-old was already an established deejay at the local KMCO radio station, where she had been hosting her own show since she was twelve. She was also an aspiring country artist. She performed that night along with the rest of the Hayride, including Johnny Horton, David Houston, and a scrawny upstart from Beaumont named George Jones. That was the second, though last, time she shared a stage with Elvis; she’d performed with him at the Hayride’s home in Shreveport just weeks earlier. “It was the thrill of my life, being at the right place at the right time,” McCoy said recently.

For McCoy, launching a radio career in East Texas during the fifties was serendipitous. Radio was still experiencing its golden age; in 1955, only half of America’s households owned a television set, but just about everybody, including in smaller towns like Conroe, possessed a radio.

In the South, a loose network of local record companies, independent producers, and promoters cultivated roots music artists, including country acts. The East Texas touring circuit was a proving ground for emerging musicians, who would often gig for months at a time, sometimes doing two or three shows a night, or sign on to package tours, which would send them to backwaters and bedroom communities all over the state. There they would perform at fairgrounds, high school stadiums, and community halls. The best publicity for these shows was via local radio stations such as KMCO and deejays such as McCoy, who served as influential tastemakers. The constellation of stations across East Texas gave small towns tangible cultural clout. Elvis didn’t put Conroe on the map. KMCO put Conroe on Elvis’s map.

The day of the concert, McCoy drove Elvis to the studio for an interview with KMCO’s station manager, which seemed to have been at least as important to Presley as the upcoming performance. The typically charismatic singer reportedly spent the entire interview nervously twiddling a piece of metal, which he ultimately managed to break. Radio, at least for the moment, was still king.

And it still is to McCoy. This year marks her seventieth on the air in Conroe, making the 83-year-old a contender for the Guinness World Record for longest-serving female radio host, first on KMCO and, since 1992, on K-Star Country (KVST), which broadcasts her shows six days a week. (Guinness lists Peruvian radio host Maruja Venegas Salinas as the record holder, but she died in 2015 during her seventieth year as host.) To Conroe, however, McCoy represents something greater. The 2010 inductee into the Texas Radio Hall of Fame is a treasured cultural institution and a repository of East Texas’s past. The number of residents with a connection to that past is diminishing as the town becomes part of the larger Houston metropolis. But as long as McCoy is on the air, those memories remain alive in the imaginations of her listeners.

The hallway leading to McCoy’s studios at K-Star is lined with dozens of signed photographs of country music royalty. Hank Locklin, Minnie Pearl, Charley Pride, Conway Twitty, and Loretta Lynn, to whom McCoy bears a striking resemblance. She remembers fondly a visit Lynn made to KMCO back in the late sixties, on a sweltering day at the height of summer. “[Loretta] was going to be on a show that night in Bryan,” she says. “She came in, and she had her hair up in curlers. And she made the remark that you hadn’t lived until you’d done a Christmas album in July.”

McCoy’s dark hair is impeccably coiffed, and her cheeks have a light kiss of blush. She’s dressed in jeans and a neatly pressed red blouse (red is her signature color). “This is the part of my life that’s kept me going,” she continues, waving around her. “It’s my love for people and for radio. And Conroe.” But she laments the passing of so many country artists from the golden era, her era. She points toward the quiet hall of faces. “Pretty soon,” she says, “there won’t be a single living person on there.”

She vows to keep their legends alive with her current radio program, The Larry and Mary Show, the flagship of K-Star, which she has cohosted with veteran radio personality Larry Galla since 1998. The show, which airs every weekday from 10 a.m. to noon, retains the poise and charm of a bygone era. The pair also records a special country classics edition that airs on Sundays, spotlighting both standards and obscure tunes by everyone from Patsy Cline to Wynn Stewart. “People will tell me that they go to church about that time, but they will stay in the car as long as they can to listen to it,” she says with a smile. She adds that she also hears from younger listeners who admit they were not familiar with many of the singers—Elvis among them—until they tuned in to her program.

During the show, Galla runs the boards and purrs into the microphone while McCoy gently responds to his patter with the kindly, soft-spoken drawl that has become her trademark. She and Galla banter between songs while she looks over her notes and the list of sponsors. When she flubs a line from one of the advertising spots, McCoy looks back at me with a smile and jokes, “I’ve only been doing this for seventy years—you’d think I could get it right.” They rewind to do it again, and she delivers it perfectly.

Over the years McCoy and Galla have refined this on-air ballad, which is every bit as tight as the classic country duets that often fill their playlists. McCoy and K-Star are like a bottle containing that last ray of old golden light, and for two hours six days a week, it’s beamed out to a world that from McCoy’s perch seems both vastly bigger and greatly diminished.

McCoy started life on a Panola County farm and, in 1948, moved to Conroe with her family in her father’s rickety Model A. The town was, like her, slight in stature but growing into its own. Conroe had been settled at the intersection of the International–Great Northern and Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe railroads in the late nineteenth century, and its booming lumber and oil industries soon made it the seat of Montgomery County.

The town’s courthouse square sits less than half a mile from Highway 75, once the main artery between Houston and Dallas before the construction of Interstate 45 began in the late fifties. The five-story courthouse, built in art moderne style, is the square’s centerpiece, looming impressively over the modest brick storefronts that surround it. Just southeast of the square is the Crighton Theatre, an Italian Romanesque–style venue, where an eleven-year-old McCoy with a booming alto won a talent show with her rendition of Patsy Montana’s yodeling classic “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart.”

“At that early age, I knew what I wanted to do: I wanted to sing, I wanted to be able to make records, I wanted my own radio program,” she says. McCoy didn’t have to wait long. Word of her performance spread to KMCO’s station manager, who invited her, in the spring of 1951, to audition for a show at the studio, which was on the second floor of the Capitol Drug building, right across from the courthouse. “I was just overwhelmed,” she continues. “[It] had the microphones and piano in there. When the ‘On the Air’ light came on, it was just a big thrill.”

She was shocked and delighted when the manager informed her that she had earned her first sponsor: Brown’s Sinclair Service Station, on the eastern edge of town. Her first gig was a fifteen-minute program on Saturdays in which she performed and pattered between songs. But singing on air was not enough for her. “I wanted to play records. I wanted to do every part that I could,” she says. She closely studied the deejay working the soundboard and turntables. “One day [the deejay] got up and said, ‘Mary, come here.’ He sat me down in the seat. And he walked off and said: ‘It’s all yours.’ ”

Soon after, she began hosting Hillbilly Corral, a weekday afternoon show. “It gave me time to get out of school,” she laughs. She spun country classics and new rockabilly hits. She also sat in when some of the biggest country musicians of the decade visited the station, from Sonny James and Carl Perkins to Jim Reeves. “[The radio station] used to [host] a lot of artists, from the fifties until the latter part of the seventies and into the eighties, when the music began to change,” she says. “The record producers would come by and visit with us. ”

Small-town radio, however, was not always fun or glamorous. “When it rained, we had to go and check the rain gauge,” she jokes about having to put together the weather report. “I don’t care if it was thundering and lightning . . . . So it didn’t do me a bit of good to have my hair done. I looked like the last rose of summer at the end of the day.” And as she started raising a family of four daughters, she would also have to balance her home and work lives, sometimes bringing her kids to the station or shuttling them to and from school between her radio programs.

Her favorite parts of the job were attending events around the courthouse square, including street dances, beauty pageants, and concerts, and performing at school dances and society halls. At the annual county fair and rodeo, she would broadcast her show remotely night after night. “I’d walk around the square, and I knew everybody,” she says. “I knew where every store was. Even though I wasn’t from Conroe, I always said this was my home.” She adds, “I just wish everybody could have grown up in that era.”

Today, Texas Highway 105 flows past the north side of the square. It is a six-lane boulevard lined with parking lots and strip malls. It’s easy to miss the turn onto Main Street. The courthouse and old facades are still there, but the square feels like a museum—except for the boutique storefronts peddling their wares to weekend tourists and antique shoppers.

McCoy’s image is one of the attractions: wander down Main Street past the Crighton Theatre, renovated after decades of disrepair, and turn left on Metcalf, and there she is, in a mural dedicated to “Conroe Legends.” She was the first inductee. Next to her are the professional motorcycle racer Colin Edwards II (a.k.a. the “Texas Tornado”), the Pulitzer Prize–winning Harvard historian Annette Gordon-Reed, and the boxer Roy Harris.

The commercial and civic heart of Conroe is no longer located in its town square, because Conroe is no longer a small town. Rather, it’s a 91,000-person exurb that stretches along I-45, blending almost seamlessly into Houston’s metropolitan sprawl of chain stores, housing developments, and congested roadways.

KMCO, too, is a vanished artifact; after its purchase by a Conroe family in the seventies and a change in call letters, the station finally went off the air in the early nineties. “It was like a curtain had been drawn, the day that I found out the station went dark,” says McCoy. “That’s how hard it hit me. I grew up in that station, so it was really sad to me.” McCoy was quickly hired by K-Star.

K-Star’s one-story office building is headquartered on the opposite edge of town between the tony housing developments and commercial centers of the Lake Conroe corridor. Still, it is one of the few remaining family-owned country stations in East Texas, a throwback to an era before rapid technological advances, corporate consolidation, and stiff competition from the internet. “I was approached many times about going to Houston,” McCoy says, referring to offers from rival stations over the years. “But I grew up [in Conroe] and just couldn’t turn my back on it.”

Not all towns last. Some flash and fizzle. Others drift in and out of relevancy, keeping a name but not an identity. Towns that endure have culture, which in plain terms means a sense of self, and that comes from their citizens remembering and forgetting together. Nostalgic anecdotes and homespun heroes are part of what makes up collective memory. Elvis came to Conroe. He probably wouldn’t come were he starting out today. But the Conroe he graced still lives on at 99.7 on your FM dial.

Conroe native Erik Morse has contributed to the Times Literary Supplement and Artforum.

This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Texas’s Radio Matriarch.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Conroe