Frank Guridy wasn’t raised on Texas exceptionalism. He’s a New York City native, a Spurs fan by marriage, and a Longhorn only inasmuch as he spent more than a decade as a professor at UT. But with his new book, The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics, recently released by the University of Texas Press, Guridy puts forth an extremely everything-is-bigger-in-Texas thesis. He argues that the state’s signature zeal to be the best—to innovate and entertain while also winning games and making money—created unprecedented opportunity and culture change for Black, Latino, and female athletes, symbolically, practically, and sometimes inadvertently. It’s a work of scholarship that’s also the stuff of barstool arguments and Twitter dunks.

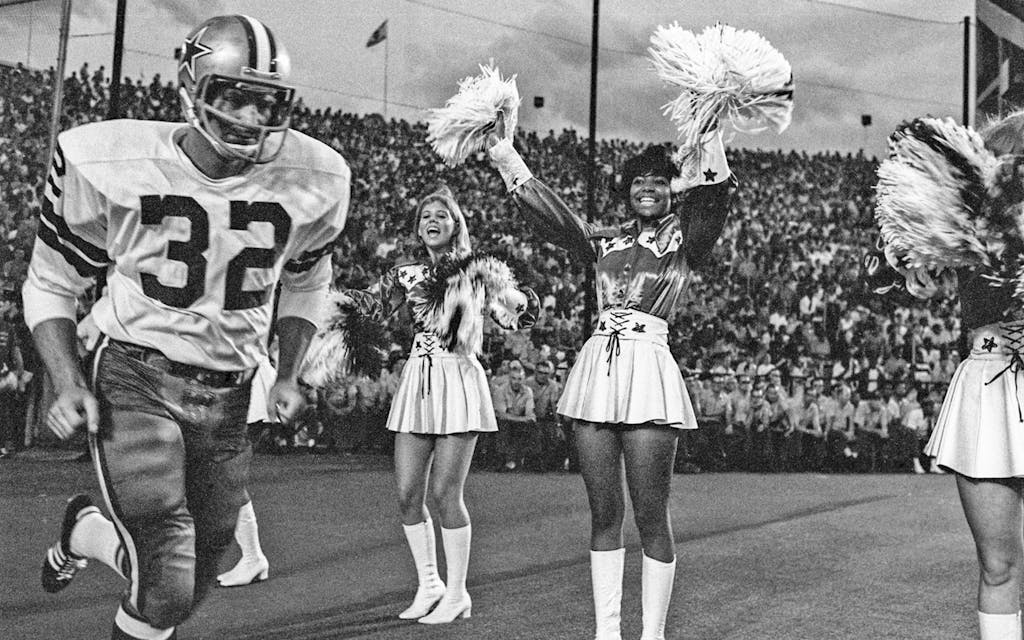

Delving into such landmark moments as the integration of the Southwest Conference, the building of the Astrodome, the “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs, the original San Antonio Spurs of the American Basketball Association (ABA), the University of Houston’s “Phi Slama Jama,” and the mythology of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Guridy makes a case that the Texas sports revolution of the sixties and seventies was every bit as history-making as Jackie Robinson’s impact on baseball and post–World War II America, or the impact on both sports and popular culture of such contemporary athletes as Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and Serena Williams.

Fast-forward to 2021, and it feels like there might need to be another revolution. While any work of history is also meant to say something about the present moment, this book feels especially timely. American sports headlines from the past month or so—about the “Eyes of Texas” debate at UT-Austin, the inequities between the men’s and women’s NCAA basketball tournaments, Major League Baseball pulling the All-Star Game from Georgia because of the state’s restrictive new voting laws—have only served to prove Guridy’s point.

Guridy spoke with Texas Monthly from New York City, where he is an associate professor at Columbia University.

Texas Monthly: Part of your book’s thesis is that it served business and capitalism to have the Texas sports revolution, at least until it didn’t. Now we’re seeing teams, leagues, and corporate sponsors saying they don’t want to be in the Native American team-name business, or the voter suppression business.

Frank Guridy: There are a lot of similarities. No doubt. These are never just moral, cultural phenomena—it’s always linked to broader political and economic changes. That was certainly the case in Texas in the 1960s and, really, going back before that, to the integration of the Cotton Bowl Classic in Dallas in the 1940s. The Cotton Bowl boosters, if they wanted to bring the best talent to play against the Southwest Conference champion, they figured out, “Well, we’re gonna have to accept Black athletes as part of those teams,” as they did with Penn State in 1948 and Oregon the year after that. That is an economic calculus, absolutely.

And that’s the story throughout my book. You see this with the coming of professional sports in Houston and Dallas. Roy Hofheinz, Bob Smith, Clint Murchison, Lamar Hunt—these are white rich men who were raised in the Jim Crow era, some of them the sons of arch-segregationists. And they decided, “We’re fanatical about sports, and we have a civic-minded understanding of what sports can do for our societies. And that means that we will have to abandon legalized segregation.” And that’s what they did.

TM: You’ve talked about growing up in New York City as a huge sports fan, but have also said you weren’t necessarily a sports scholar before writing this. How much of the Southwest Conference history did you know going in?

Frank Guridy: I knew a fair amount as a fan. All those [SWC] programs I encountered as a kid watching the Cotton Bowl on TV. And I kind of knew about Doak Walker. A Texas football legend. You can’t understand the expansion of the Cotton Bowl without understanding that story, and then in order to understand SMU with Jerry LeVias, and then eventually with the Pony Express, and the [NCAA] death penalty, you’ve got to go back to Doak Walker. He just has an enormous impact in the Jim Crow era.

TM: Most people know that SMU made Jerry LeVias one of the first Black players in the SWC, but he was actually preceded by Warren McVea at the University of Houston, which was not yet a member of the conference. And while the story of Texas Western becoming the first team with an all-Black starting five to win a men’s NCAA basketball championship has been told plenty of times, you write about the fact that Guy Lewis was also recruiting Black players to UH in the sixties.

FG: I was interested in the people who actually made the decision to stand outside of history. The story is not just the economics and the winning, but that a historical figure—a person, a human being—decided to buck the trend. That’s what Hayden Fry does in 1965, when he signs Jerry LeVias, and that’s what Bill Yeoman does in 1964 when he signs Warren McVea, and Guy Lewis is another one. He’s from East Texas, right? He could have just gone along with the program, and he didn’t.

I wanted to focus on that moment when inclusion happens. Why did they decide to allow Black athletes to be in the space that had been completely separate? They wanted to win, of course, but they also decided: “No. I’m not going to go along with the program. I’m actually going to use my privilege to change history.”

TM: In your writing about Lewis, and Houston’s Fonde Recreation Center, and the Astrodome, you also make a case that isn’t news to Texans, but might be to the rest of the country: that Houston is our most American city.

FG: I’m very comfortable making that claim! Absolutely. A lot of Houston folks make the case that Houston’s the most diverse city in the country, and in a lot of ways Houston is completely overlooked on the national landscape. You can’t understand what happens in the sports world, and certainly in Texas in that period, without understanding what’s going on in Houston. Its particular ethnic mix, the role of the oil economy—it’s not by accident. The Astrodome was built there because it’s a wonderful combination of farsighted sports entrepreneurs teaming with athletes and activists who were coming of age in the civil rights struggle.

And I think that’s why the Astrodome became such a beloved institution. Because even though it’s the first indoor stadium, and the first stadium to have luxury boxes and the bells and whistles and the amenities that we see at all stadiums today, it catered to a wide demographic, in ways that stadiums don’t now. Stadiums at their best work when they really serve a larger purpose than just, you know, going to see the Yankees or going to see the Texans. And that’s what the Astrodome had.

TM: The SMU “death penalty” scandal, in which the team had its 1987 season canceled after paying players, comes at the end of your story. You put that in the historical context of college football becoming the corporate and TV-driven machine we have today. It also seems that a big part of the college football fan base now looks back on that and thinks, “Yeah, they broke the rules, but it wasn’t less ethical than what we have now.”

FG: That is sort of the conclusion I came to. In the book, when I use the term “student athletes,” I usually put it in quotes—kind of critiquing that whole construction, which was made by the NCAA in the 1950s.

I was a professor at UT, so I saw it firsthand. You have a number of student athletes who actually try to be students, but in terms of the big so-called revenue-generating sports, those people are not there to be students. They are there to work for the institution. And what you also see happening is that eventually, the compensation grows much bigger for coaches and athletic directors and the rest of the people who run these operations, [but not] the actual players on the field.

So in a lot of ways I don’t see it as an ethical question anymore. These are laborers, many of them of Black, and, in fact, they should have been compensated in some way. And so my read on that is that in some ways, the SMU boosters and the university were right. Certainly they were breaking rules and making all sorts of violations. But in some ways they were just doing what history was pushing them to do at that time.

TM: And you can’t really separate race or class from the “Oh, they should just be happy that they’re getting a free education” mentality.

FG: That’s exactly right. And I think that’s what informs so much of the animus toward athletes who protest. One of the consequences of that era of integration was [that] white fans figured out they could still love a Black athlete on the field, but don’t have to necessarily see them as equals.

The whole notion of “shut up and dribble” is the white public—not all white people—thinking that they’re owed a debt of gratitude. That [athletes] should be grateful for the opportunities they have, and that they should forfeit the citizenship right to expose themselves as people. That they shouldn’t care about anything but producing revenue for their teams and the universities. And that’s just a completely dehumanizing, racist position and sexist position to take.

What we’re seeing in this generation of athletes is that they’re really pushing back hard against that, showing that you can be a beloved athlete and be an American citizen who cares about voting rights, and cares about justice. Those are not mutually exclusive identities. We are seeing a lot of examples of that now. And certainly in the period that I wrote about, there were a lot of people like that.

TM: I presume you’ve been following the “Eyes of Texas” saga pretty closely.

FG: I have, yeah. What makes it interesting to me as somebody who worked there for eleven years is that I think the institution has done a lot in overcoming that legacy. Certainly in terms of the way they were hiring more diverse faculty during the time I was there. Between 2001 and 2013, UT-Austin hired something like seventy African and African Diaspora Studies faculty. That’s really significant. I’m at Columbia University, and we could never dream of doing something like that here.

So in terms of the faculty, in terms of the programming, in terms of a lot of the public culture, I think that UT-Austin, given its Southern, Jim Crow roots, has actually done a lot in addressing those issues. But clearly there’s more to do. The Black Lives Matter movement [has highlighted] the ways in which lingering and ongoing white supremacist traditions continue in our institutions. “The Eyes of Texas” has gotten caught up in that, and the students, or a significant portion of them, feel like something has to change.

Because even with all the changes that we’ve seen, if you go to a UT-Austin football game, you can’t escape that legacy. When you see the predominantly Black football team out there in that context, the specter of segregation remains. I think that in some ways, the students are responding to that as much as they are the actual history of the song. The song is relevant, but it’s really about the whole picture, which has just been exacerbated by the gross inequities between the value that the football players produce and the amount of money that the institution and coaches and athletic administrators make from their athletic labor.

TM: So does it feel like we are in a hopeful moment, after a long period of less hopeful moments?

FG: Yeah, if I’ve been encouraged by anything over the last year, it has been the power of the social movements we’ve seen in our country. You’re seeing [them] force questions to the floor that have been ignored. You’re seeing the ways in which activism matters. And you’re seeing the ways in which it even affects policy.

And to see athletes join that movement has been inspiring to me. Because I see sport as something that is more than entertainment. It’s something that should really epitomize the values of society, and that’s what we usually say it does, right? The kinds of things we often say about sports—that it facilitates teamwork, that it’s an even playing field and so on—those are aspirations. In terms of really adhering to the ideals that we supposedly live up to, or profess in this country, we have to make some more substantial changes.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.