Nathan Harris’ extraordinary debut novel, The Sweetness of Water, takes place in the fictional town of Old Ox, Georgia, in the waning days of the Civil War. In the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, brothers Prentiss and Landry find themselves freed but confronting the question, What next? Despite its historical setting, this story asks questions that feel intensely relevant today. What’s the price of dignity? What’s the legacy of slavery and racial violence? And what does it really mean to be free?

The 29-year-old Austin author earned his MFA last year from the University of Texas’s Michener Center. He opens his book (published by Little, Brown, and Company on Tuesday, and just selected by Oprah for her book club) with a white, pacifist landowner, George Walker, losing himself in the overgrown forest of his property on the edge of Old Ox. It becomes apparent early that George is a man in search of direction, both literally and figuratively. He has “developed a hitch over the last few years, had pinned it on a misplaced step as he descended from his cabin to the forest floor,” Harris writes, “but he knew this was a lie: it has appeared with the persistence and steady progress of old age itself—as natural as the lines on his face, the white in his hair.”

As he grapples with aging, George roams the land in search of a near-mythical creature, a beast that has eluded him since childhood but which he has seen and still believes to be out there. “I often wake to its image,” he says, “as if it’s trying to alert me to its presence nearby . . . it travels through my head like an echo, bounding through my dreams.” It’s clear early on the beast is a metaphor for George’s former self, full of conviction. In old age there’s a rift with the person he knows he is and the person (or persona) he’s been forced to accept to keep peace with his neighbors in Old Ox: capitulating, spiritless, ineffectual in matters both big and small. In the process, he’s ceded his dignity.

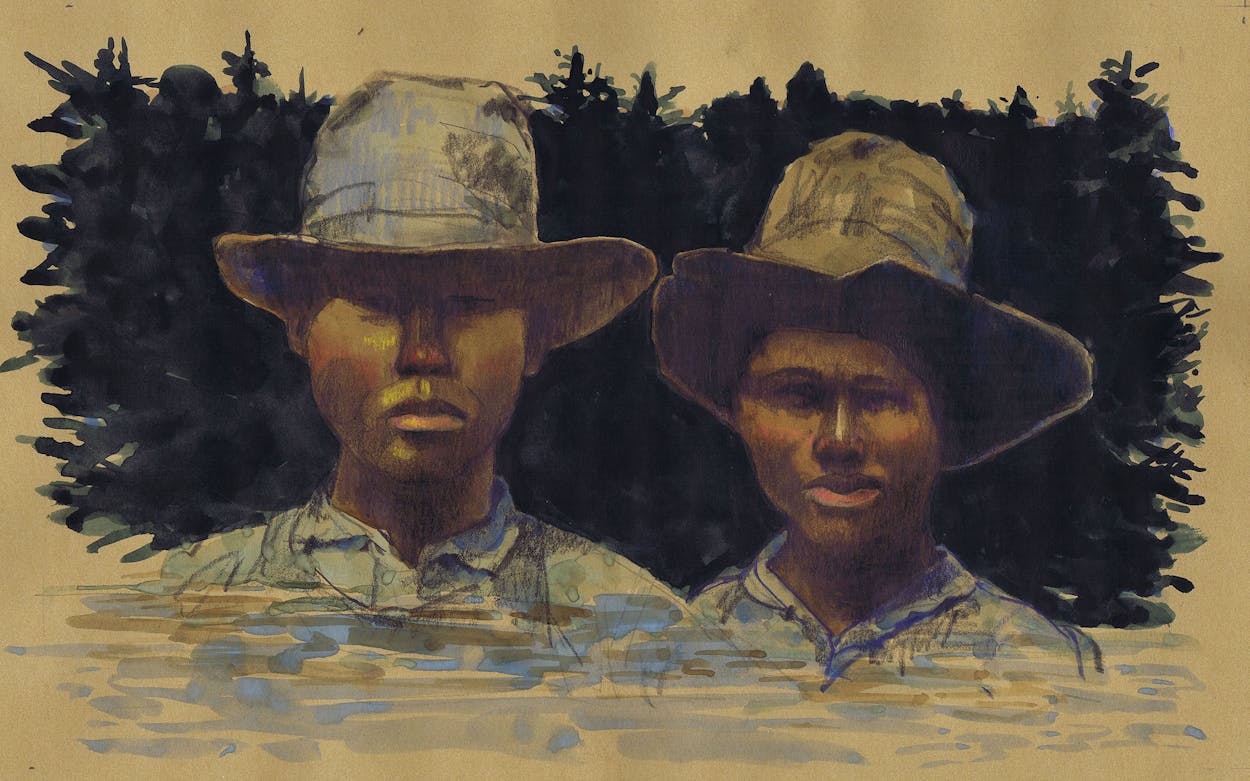

The search for this beast provides a sense of escape for George—in part from his wife, Isabelle, who is inconsolable after the disappearance of their only son, Caleb, a Confederate soldier. George also seeks refuge from the turmoil of his community, which is struggling to come to terms with the Union soldiers in its streets and the upheaval of the nascent Reconstruction era. It’s with this backdrop, and in the tranquility of the forest, that George happens upon Prentiss and Landry, brothers recently freed from an adjacent plantation. The brothers are in poor shape, emaciated and dressed in “britches as ragged as if they’d fitted their legs into intertwined gunny sacks.” Like many of the recently freed, Prentiss and Landry are unsure how exactly to bridge their desires with their reality. They know that if they are to thrive, they must leave Old Ox, but to do so they’ll need money. Their hopes reside in the North, where they plan to reunite with their mother, if she’s still alive. Like Walker, they are unsure but hopeful of what’s out there.

The brothers, willing to lend a hand in tracking the beast, eagerly accept George’s offer to have them work on his farm. The brothers save their earnings little by little. In turn, George finds some direction as he throws himself into the work of clearing his densely wooded homestead to sow a crop of peanuts. And then one day, Caleb, the son he thought was dead, appears on the doorstep. Nothing is ever the same again.

Harris expertly introduces explosive plot twists across parallel threads—between Caleb’s story and Landry and Prentiss’s, with Isabelle often playing interlocutor. There’s an elegant interplay among all facets of the narrative that at once raises the stakes for all the characters while gesturing toward a larger world outside Old Ox. The overall effect is a dazzling world-building that makes the relatively compact novel feel much larger than its 368 pages. I was immersed in the world that these characters inhabit.

Throughout the novel, Harris doesn’t so much give us the backstory as share the gossipy looks, the slights, the anxieties within characters and community members alike. This is especially true regarding Prentiss and Landry, but also Caleb, who has a clandestine romantic relationship with a fellow soldier. After Landry sees one of their trysts in the woods, Caleb’s lover decides he has to kill Landry in order to keep the secret hidden. If Caleb had played both sides in the beginning—the son of his pacifist father and the Confederate war hero come home—he must now choose one destiny and fall into it. This is the dilemma that ripples out into the rest of the novel and touches every character in Caleb’s orbit.

While all the characters in this novel yearn, there’s a certain palpability to the yearning of the two brothers. Harris somehow manages to weave emotion into the smallest of moments: frying up a sliver of bacon; copying the stitch pattern of a knitted sock in just the right shade of blue; experiencing the beauty and brutality of the wilderness with all five of the senses. Harris’s abilities are on full display in passages that feature Landry’s obsession with water—an important motif throughout the novel.

“The slime at the bottom of the pond grazed his toes now when he let it,” Harris writes of Landry. “Small guppies flitted before him, darting about like children at play. He took a deep breath and dunked his head. Silence consumed him. He was entombed in tranquility, in the boundlessness of his floating, his weightlessness.” Such moments not only subtly underscore the individuality and desires of the characters, but also the indignity and horror of having their humanity stripped from them extrajudicially. Or worse, judicially, as happens toward the end of the novel. Parallel threads in the narrative collapse into one, and Old Ox devolves into mob rule and mob justice. The fallout is catastrophic.

Everywhere in Old Ox, the ideology and violence of the plantation system persists. The Union soldiers succumb to local money and politics. The white-supremacist ideology of the Confederacy doesn’t disappear so much as it is repurposed by Union generals to advance their individual agendas. Just as there is an interplay among parallel threads in this book, there is also the uncanny interplay between the present and the past. Harris’s writing made me think about how the legacy of slavery is still with us, and how well-meaning whites can be complicit in its continuation. The overall effect is a deep interrogation of white fragility and the ease and convenience of white cowardice in the face of injustice.

Several uncanny scenes in the novel bring to mind George Floyd and other victims of police violence. In one horrifying scene, Prentiss, confronting Old Ox’s sheriff in the wake of a murder, is knocked to the ground by the sheriff’s deputy before feeling “a grip about his neck—Wade Webler locking him in a chokehold,” Harris writes. “Prentiss’s heart beat so hard he felt it in his head. He could not free himself from this bear of a man and had begun to panic, squirming toward his own unconsciousness.”

In reading Old Ox scenes of mob justice, corrupt officials, and a community’s use of violence as a political tool, one can’t help but notice the echoes of the brand of white-supremacist ideology behind January’s Capitol riots, the impunity of the Trump presidency, and the rise of the far right. There is an aspect of this novel that asks the reader to move beyond the idea of a savior North and damned South. It asks us to consider white-supremacist ideology not as a uniquely Southern phenomenon, but as an uncomfortable truth and feature of the entire American endeavor, especially of the criminal justice system. Old Ox is in Georgia, but it is also everywhere today.

Harris writes with the confidence and command of a seasoned master of the craft. And, of course, the magic of his sentences is in the details—everything is historically accurate and painstakingly researched, whether he’s describing the reprieve of a fresh tick mattress or the complexity of growing peanuts in Georgia soil. This novel is simply the best I have read in years.

- More About:

- Books