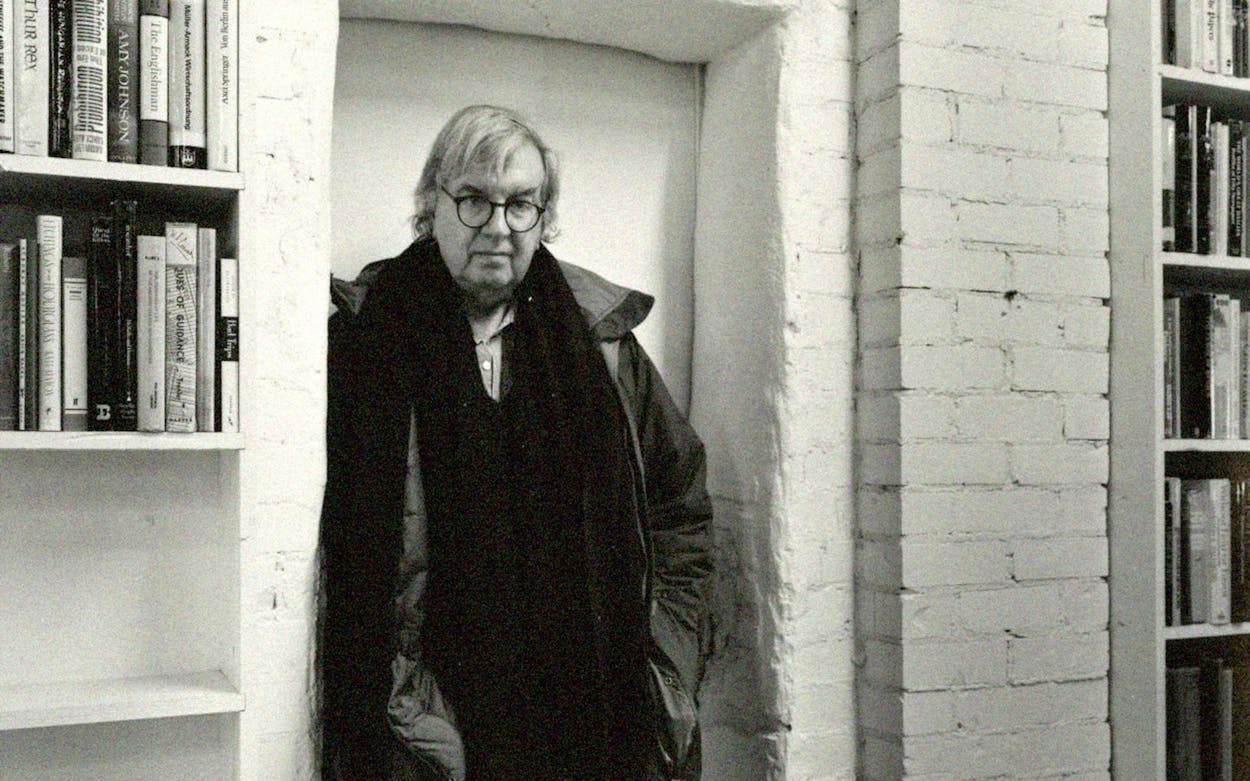

In the days following Larry McMurtry’s passing, many Texas wrote heartfelt remembrances of the man and his work. The best, I thought, came from people recalling their trips to McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, hoping to see him around town. Even in the versions of these that lacked an actual encounter with McMurtry, Archer City somehow still shone. During the month since McMurtry’s death, I’ve revisited some of his work to see how much of Archer City he left behind on the page. What did he say about the place while he was there? For the uninitiated, what would serve as the textbook for a crash course on Larry McMurtry’s Archer City?

The town is of course immortalized in his fiction, most notably through his novel The Last Picture Show. And even if his fiction work is where McMurtry shone the brightest, he also published scores of nonfiction work, which I consider some of his best. Archer City is there in 2001’s Paradise, written as McMurtry’s mother was dying. It’s there in his early collection of essays In a Narrow Grave. And it’s there in the trio of memoirs he wrote later in his life. But the town is usually mentioned in passing. However, that’s not the case with McMurtry’s Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen: Reflections on Sixty and Beyond. For anyone interested in seeing Archer City through his eyes, Walter Benjamin is the closest you’ll get.

McMurtry wrote the book in 1999, when he was living in Archer City full time—more or less for the first time since his youth—with hopes of getting his bookstores up and running. The book jacket claims that it is “as close to an autobiography as his readers are likely to get.” He opens in perhaps the most McMurtry way ever: sitting by himself in a Dairy Queen on the outskirts of town, drinking a lime Dr Pepper and reading an obscure essay by Walter Benjamin called “The Storyteller.” Much of the book is told from his booth at the Dairy Queen, and McMurtry spends plenty of time explaining his experience of growing up in Archer City and how the action around town, or lack thereof, shaped him. —Paul Knight, associate editor

Join the BOXT Wine Club

At some point this year, I realized I needed to cut back on my daily imbibing, which had increased during the course of the pandemic and other disasters. So, I started drinking wine out of a box.

This might seem counterintuitive, but hear me out: Boxt, founded by Austin businesswoman Sarah Puil, is a new monthly subscription service offering your choice of one of six varietals of wine (three red, three white), each of which comes in a recyclable, reusable, aesthetically pleasing pine box that contains the equivalent of four bottles. Think of it as a good house wine on tap in your fridge. Because the wine has a shelf life of about thirty days, you can drink on your own schedule—that one-glass-a-day maximum cautioned by health experts is a lot easier to achieve when you don’t feel the pressure to finish off a whole bottle.

The wines, alas, like many of our state’s newcomers, come from California (Napa, specifically), and they are listed simply as numbered profiles (I’ve enjoyed Number One [“Bright. Crisp. Dry.”], similar to a New Zealand sauvignon blanc). The site doesn’t offer much else in terms of information on the winemaking; it promises just that these are premium wines inspired by the house wines Puil enjoyed during her European travels. And this isn’t necessarily a money-saving service: the most popular membership option requires a $19.99 annual fee (which covers all shipping for the year) and then $74 a month (the equivalent of $18.50 a bottle). But Boxt can be an attractive option for those who know what they like. (Maybe Number Six [“Sweet. Juicy. Velvet.”], like a California zinfandel, perhaps?)

I relish exploring and learning about wines—especially those from Texas—too much for this to be my default option, but I’ve enjoyed the no-pressure ease of pouring a glass of wine for dinner or happy hour when the mood strikes. There’s an eco-friendly component I’m happy to toast to as well: for every box it makes, Boxt plants a tree via its nonprofit partner, One Tree Planted. —Kathy Blackwell, executive editor

Attend an Ortega’s Kitchen Pop-up

I have vivid memories of eating at the Ortega’s Kitchen food truck, started by high-school sweethearts Erica and José Ortega. At the mobile truck’s various locations across Houston, I would sit with friends under string lights hung over picnic tables, dipping tortilla chips into homemade salsa (which I’d sometimes just eat with a spoon). After Ortega’s temporarily shut down during the pandemic, I missed these moments, but the truck has recently started to do occasional pop-ups again. While they specialize in Mexican food, the Ortegas meld Houston’s many cultures into their cooking, making for a business that both tastes and feels like home. The truck serves everything from birria tacos to fried rice to aguas frescas to enchiladas, complete with excellent red and green salsas, of course. Follow Ortega’s Kitchen on social media to be alerted about the next pop-up. —Aarohi Sheth, editorial intern

Grab a Burger From Bad Larry Burger Club

In the past year, ordering takeout online has become second nature for my husband and me. But beyond our regular rotation of favorites, the occasional trendy food pop-up requires a fast-as-lightning ordering finger. While Austin’s Bad Larry Burger Club technically existed pre-pandemic, it caught our attention only last fall, and we’ve since been lucky enough to win the online ordering lottery a few times (time slots generally sell out in mere minutes). Chef Matthew Bolick would show up in a parking lot or take over an existing food truck and dish out smashed-patty burgers from a metal chute six feet long (to promote CDC-recommended social distancing, obviously). Nothing else is on the menu except the double-meat, double-cheese burgers—which are topped with just pickles, onions, ketchup, and mustard—but each one is a perfectly juicy, delicious experience that will have you licking melted cheese off your fingers and wondering if it’s not a bad idea to order two next time. —Jenn Hair Tompkins, associate art director

- More About:

- Libations

- Books

- Wine

- Larry McMurtry

- Houston

- Austin

- Archer City