When singer-songwriter Blaze Foley was murdered at the age of 39, in February 1989, he had released only one single and an LP that he’d mostly distributed himself. He had spent much of the previous two decades in obscurity, making the rounds at clubs in Austin and Houston, crooning his introspective folk-country stunners, which melded starry-eyed romance and critical self-reflection.

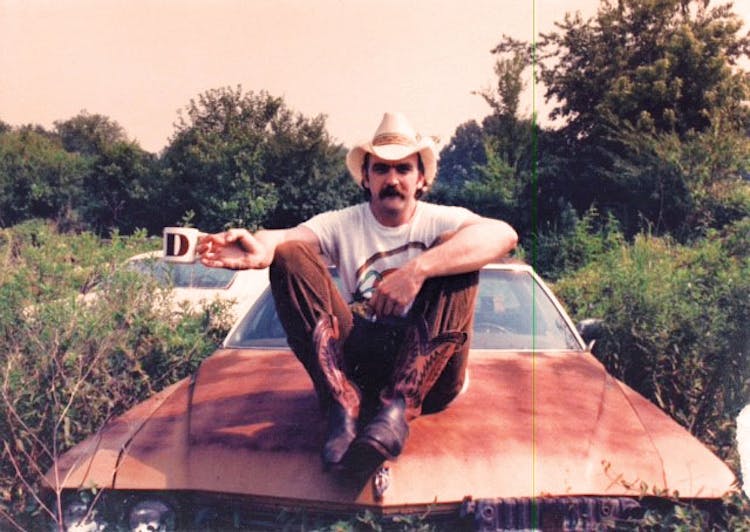

To many who knew him, he was an eccentric backwoods sage. He was dubbed the Duct Tape Messiah after he began binding his tattered boots and clothing with adhesive to mock the shiny attire worn by urban cowboys. Townes Van Zandt once described him as “one of the most spiritual cats I’ve ever met: an ace picker; a writer who never shirks the truth; never fails to rhyme; and one of the flashiest wits I’ve ever had to put up with.”

Foley was also an infamous drunk who was prone to self-sabotage. He died virtually penniless.

Yet since his death, he has become something of a folk hero. Beginning in the late nineties, several previously unreleased albums were made available to fans. John Prine, a hero of Foley’s, covered one of his songs, the elegantly observant “Clay Pigeons,” on his Grammy Award–winning 2005 album Fair & Square. The documentary Blaze Foley: Duct Tape Messiah was released in 2011. And this month marks the debut of an Ethan Hawke–directed biopic, Blaze.

The Austin-born Hawke was attracted to Foley’s story precisely because it disrupts typical Hollywood narratives. “One of the things I don’t like about most music movies is that they’re always about somebody famous, as if famous people are the only people who have interesting stories to tell,” Hawke says. “I spent my life in the arts, and almost all of the interesting people I’ve met, the most talented people, have faced just utter indifference. I thought, wouldn’t it be fun to make a music picture that doesn’t have the scene where the guy makes it?”

There were moments when Foley flirted with a breakthrough. In 1980 he landed a coveted spot opening for Kinky Friedman at New York City’s famed Lone Star Cafe but was subsequently excoriated by the headliner for his drunken performance. Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard cut a version of Foley’s “If I Could Only Fly” for their 1987 duet album Seashores of Old Mexico. Haggard, who had likely never heard of Foley before that recording, released a solo version of the song in 2000, making it the title track of his fiftieth album. Foley, of course, was long gone by then.

Toward the end of his life, Foley befriended an older man named Concho January. Foley had multiple—at times violent—scuffles with Concho’s son, Carey, over what Foley perceived to be an abusive father-son relationship. It came to a head when Carey shot and killed Foley at Concho’s home in South Austin. According to playwright and author Sybil Rosen’s 2008 memoir, Living in the Woods in a Tree, the lyrics to “If I Could Only Fly” were affixed to his casket. As he was lowered into the ground in Austin, mourners threw Bibles, picks, and capos into the grave, covering a casket sealed by his friends in layers of silver duct tape.

Hawke based the film on the book by Rosen, whom some knew as Foley’s wife, though they were never legally married. She met the man she called Depty Dawg (he had already shed his birth name, Michael David Fuller, but had not yet adopted Blaze Foley) in 1975, while she was working as an actor at an artists’ colony in Georgia. Foley, who grew up in both Georgia and Texas, had signed on to play in the house band and help with occasional carpentry projects. Days after meeting, the couple began a whirlwind romance and moved into a tree house tucked into the woods, where their landlord allowed them to live rent-free. There, they spent the next year honing their respective crafts. Though their relationship lasted only two years, the couple bouncing between Georgia and Austin and Chicago all the while, it was the most fertile creative period of Foley’s life. And Rosen was his greatest muse.

Hawke pulled some of the film’s most striking dialogue almost directly from Rosen’s book. In one scene, Rosen, played by Arrested Development’s Alia Shawkat, and Foley, by musician Ben Dickey, are curled up in the back of a pickup heading down a tree-lined country road. “So are you going to be a big country star, like Roger Miller?” she asks. Blaze, laughing, replies, “I don’t want to be a star. I want to be a legend.”

Before they began filming, Hawke asked Rosen, who cowrote and acts in the film, to keep a diary of her experience on set, a selection of which we have published here. —Abby Johnston

November 28, 2016

Village Studios

Jackson, Louisiana

Forty-one years ago, I described living in a tree house with Blaze Foley as being like falling out of a dream. This afternoon, landing in the parking lot of the film studio where much of Blaze will be shot, I feel the way I did at 25—as if I’ve been dropped into a mysterious world without quite knowing how I got here.

At 2 p.m. Village Studios is muggy and quiet as naptime at summer camp. It does seem like a village: picket fences border a row of modest, popsicle-colored town houses; an old caboose is parked incongruously, like an immovable red bull; and directly in front of me are two quasi-antebellum houses with broad verandas, one oval-shaped with a riverboat bow. The Long, Hot Summer was filmed here. Village Studios lore maintains that Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward met on these jasmine-scented porches.

All at once, Ryan Hawke, a producer on the movie and Ethan’s wife, races out of one of the houses and hugs me. “A person, a real person!” she cries, meaning me. I suppose it must be odd to know someone mostly as a character in a movie script and then have them pop up in the flesh a week before filming begins. It feels a bit odd to me too.

Ryan and I met once before, six months ago in New York City, when she and Ethan and I had dinner together. We were all nervous, but we wanted the same thing: to make a loving movie about Blaze and his music. Collectively, the three of us are like a couple who get pregnant on the first date. You don’t really know each other, but you’re suddenly committed to bringing this baby into the world.

Ben Dickey, who will play Blaze, appears—it’s the first time we’ve seen each other. I am stunned by his size—towering like Blaze—and charmed by his Huck Finn smile. His hug is huge, warm, engulfing, and shockingly familiar. Our emails back and forth over the past month have woven us into a kind of karmic cloth that binds us through Blaze. Writing three, four times a day, we grappled with Blaze’s myth and how it differed (or not) from the man I knew. Mostly, we talked about love—sexual love, true love, the kind of love Blaze felt for the suffering world. We wrote about tree houses and songwriting and where inspiration comes from. I saw so much of Blaze naturally occurring in Ben, who is a musician himself—his artistry, his sensitivity, and his struggle—I knew he had only to open himself to the story to make Blaze come alive once more.

There’s no small talk; there isn’t time. The film has come together so quickly. Ethan and I first talked in April, and now it’s November, with only seven days before shooting begins. We turn into the art department, which is housed on the first floor of the boatlike house. The large room, lined with desks, is basically a Blaze museum. He covers the walls. There are tree house pictures, snapshots of my late parents (which I find bizarre, like they’re still watching me), and an array of images from Blaze’s other lives. He lived a lot of them in one.

I meet art director Elissabeth Blofson and production designer Thomas Hayek. Within minutes, I am showing them Blaze mementos: a stack of love letters; the 1979 45 rpm single of “If I Could Only Fly” inscribed to me; the ponytail he cut off and gave me when we broke up in Chicago. Thomas’s wide grin fades; he begins to cry.

Ben, Elissabeth, and Thomas take me to see the tree house and the sets for our Austin and Chicago apartments. It’s intoxicating and vaguely disorienting to see the places Blaze and I lived filtered through others’ vision. The awareness that, for the next five weeks, the only firm ground beneath my feet will be the unrelentingly surreal nature of this experience slowly begins to wash over me.

Later, at night, I meet Alia, who plays me, still a strange thing to write. Small, dark, and curly-haired, she gasps when she sees me and rushes into my arms, like a living mirror image or a dream of someone I used to be.

December 5, 2016

T&T Liquor & Lounge

The Austin Outhouse

It takes so many people to create one illusion: designers, builders, electricians, buyers, dressers, caterers, visual artists, hair and makeup artists, costumers, prop masters, soundpersons, boom-ops, cameramen, lighting designers, drivers, production assistants, location managers, grips, gaffers, and best boys. Ethan gazes around the spacious T&T Liquor & Lounge—the movie’s homage to the Austin Outhouse—where Blaze’s last performance will be filmed. “I love this space,” he declares, his voice husky with awe. “I want something good to happen here.”

He gathers the cast and extras, the technical crews. He says we need a sense of urgency but that we’re in no rush. I take this to mean we’re to attend to each moment with intention and intensity and forget about time. The scene itself has a built-in urgency, with Blaze trying to record as many songs for the live record as he can in two hours. Ethan tells the extras that the portrait we’re painting here is of an ordinary night in an ordinary bar. He places people at the cafe and pool tables.

We do take after take, going after the perfect shot in one smooth sweep. The band must come into the bar just as a cook emerges from the bathroom—it all has to be choreographed, timed, cued. The camera is an alive thing with numerous protrusions, crouching buglike on cinematographer Steve Cosens’s shoulder. His assistants hover over it like tender caretakers. Ethan follows Steve, holding the hand monitor, pulled into what he sees there, a smiling conductor waving an arm, willing this barfly ballet to life.

At certain moments, like when I spy Ben as Blaze in his duct-tape finery and fulsome beard, time suddenly collapses. Ben has made Blaze’s limp his own; the hitched gait projects vulnerability and endurance. Each time I see him, just for a second I think, “Oh, there’s Blaze, he’s here, he’s come, this is not a dream.” But it is a dream of sorts, a conjured realm where life and death can permeate the membrane of illusion that separates them.

December 9, 2016

House in St. Francisville, Louisiana

Concho’s House

Crew call today, 11:30 a.m. We are filming into the night. The last scene will be Blaze’s death. The location, a stand-in for Concho’s home in Austin, is a half mile from the Mississippi River, a slumped wooden house held up on rock pillars, gutted by flooding and neglect.

Martin Bradford, the actor who plays Blaze’s killer, is on set today. I hug him. “You have the hardest job,” I tell him. “We’re going to get this right,” he replies.

By nightfall, the weather is stinging cold. Charlie Sexton—our Townes Van Zandt—kindly keeps me company on the set. Thin, sensual, and sly, with a shock of unruly hair, Charlie knew Blaze in Austin.

I wonder at my lack of tears as we’re filming Blaze’s death. Charlie calls it anesthetized sensitivity. I don’t want to be numb. I don’t want to turn away. I want to hold all of it. Writing the memoir felt like Blaze—in whatever afterlife he occupies—was insisting I restitch his memory back into mine. But now I’m being asked to bear witness to events I wasn’t present for and never wished to be. Though I’ve pictured Blaze’s death a thousand times, tonight it feels like the force of imagination itself has finally brought it to life right in front of me. The shock and proximity to horror, even if it’s make-believe, cuts too deep for tears.

Mercifully, the actual act happens offscreen. Ethan is trying to avoid what he calls the pornography of violence. Watching from the monitor, I see a flickering blue TV light through a window, then the flare of the gunshot; Blaze coming out, bleeding, dying, wending to the street; his killer trailing in a frenzied panic. I feel the anguish from both of them.

Blaze looks up into a streetlamp, its light bright as a celestial beam. The crew huddles around the monitor, watching as he collapses in the street. Their faces are as pale and drawn as mourners. It’s almost as if he isn’t dying alone this time.

The scene has a terrible beauty I had not anticipated.

December 15, 2016

Village Studios

Radio Station

How does one become a legend? What makes that happen? Is there a tipping point, an alignment of stars and circumstances that suddenly causes a life to blossom into fable?

I’m sitting in the gray, claustrophobic “radio station” set where Charlie, as Townes, is being interviewed about the late Blaze. Charlie mines Townes’s oddness, suavity, depth, and arctic detachment in powerfully convincing fashion. It was so wise to cast musicians as musicians. Ben and Charlie know this performing life and what it costs.

In the radio station with Townes is Zee (played by Josh Hamilton), Blaze’s perennial sidekick, a composite character of musician Gurf Morlix and two other Texas and Georgia running mates. Townes is unabashedly mythmaking, describing Blaze’s rapturous meditative encounters with Jesus and Buddha, while Zee quietly underscores the man, eye-rolling as Townes goes on and on.

There’s obvious friction between Townes and Zee over Blaze’s legend versus his humanness. I never knew the legend. I only knew the man. At times I’ve resented the legend for the price he had to pay for it. But I can feel its pull. I might not be sitting here otherwise.

December 15, 2016

Village Studios

Sybil’s Chicago Apartment

Mid-afternoon, and we’ve moved to an upstairs “apartment” where we’ll film Blaze and Sybil’s breakup. What made me think there was nothing more to learn about our goodbye?

The scene hangs on Blaze’s song “If I Could Only Fly,” written for me—for us, really—in early 1977. Blaze has been on the road, and now he’s come home to sing this new song for Sybil. Between Ben’s broken delivery and Alia’s raw and tender performance, Blaze’s presence flares up in me, illumining the loss, exposing its inevitability. Costumer Lee Kyle puts a hand on my shoulder. “My heart is breaking,” he whispers. “I can only imagine what’s left of yours.”

Lots of noses are blown after each take. Ethan calls it “a breakup between two kind people.” He says he’s proud of Sybil the character for taking care of herself.

“We wanted to be artists,” I say. That’s what brought us together. And that’s what broke us apart.

December 16, 2016

Village Studios

Rosen Family Apartment

When Ethan and I discussed the possibility of me playing my mother, Jeannette, in the movie, I told him I was born to play the role. He laughed and said, “You won’t be playing a portrait of your mother. You’ll be playing the woman that serves the film.”

I asked that the acting credit for Jeannette go to Jean Carlot, the name Blaze gave me in the tree house for my future on the big screen. This morning is Jean Carlot’s debut. Her name is on the dressing-room door, scrawled fittingly on green duct tape. On set, Ethan calls me Miss Carlot. He introduces me as the famous French actress and compliments me on the work I’ve done on my Southern accent.

It’s chilly today, so a fire is built in the fireplace on the Rosen family apartment’s elegant set. Ethan places Alia and me on pillows, tucked into the hearth on either side of the flames. Sitting by the fire, sharing a mother-daughter cigarette, we improvise a scene. Jeannette surprises me. She’s somehow cooler, less fragile than the scripted Jeannette, with an unexpected sturdiness. But then, Alia has an innate sturdiness. I guess our filmic DNA is lining up.

In the afternoon, we shoot another scene with Blaze, Sybil, Jeannette, and Sam, my father. Sam is played by playwright Jonathan Marc Sherman. We met last night, and we are already knit as family. Jonathan radiates goodness, so he’s perfect for Daddy. The situation makes me feel like Faye Dunaway at the end of Chinatown: He’s my father, he’s my husband. He’s my father and my husband.

By nightfall, Miss Carlot’s day is done. In the hair and makeup trailer, wiping off mascara, with Alia sitting on my right, we notice our arms—my right, her left—lightly toasted from our scene by the fire. They bear a matching mirrored pixilation of identical red dots.

January 4, 2017

Eastern Louisiana

Mental Health System, Visiting Edwin

6 a.m. crew call. We drive through the darkness to the hospital for a day of shooting, mostly of Blaze; his father, Edwin; and his sister Marsha—scenes based on an actual trip Blaze, Marsha, and I made to see Edwin in Dallas in 1976.

It’s still dark when we arrive at the institution. Tall outside lamplights and a few dim interior lights reveal austere nineteenth-century brick and wooden buildings beside recent additions, some that resemble modern elementary school classrooms and a warren of steel barns.

Before we shoot, we attend a safety meeting with hospital security personnel, cheerful men and women in brown-and-green uniforms. They tell us not to wander around alone, to use the provided shuttles between locations and base camp. Still, we are jazzed to be in this unusual, unsettling location because Kris Kristofferson is on set today.

Ethan cast Kris as Blaze’s father, giving the role an immediate luster that the original, I’m sorry to say, did not have. At eighty, Kris is small, frail; he suffers from short-term memory loss, which at times gives him a bemused, wondering look. He’s handsome as ever, with moonlit hair and disturbingly blue eyes.

We film his scenes in an abandoned wing of the hospital, green-tiled and utilitarian. The rec room where Blaze and Marsha (played by musician Alynda Lee Segarra) visit their father is bare except for splotches of colored tiles on the walls. Blaze and Marsha sit across from Edwin and sing “Pearly Gates,” a song from their childhood as itinerant gospel singers. Ben’s and Alynda’s voices glide together in pure, braided harmonies, the way families can.

In a different scene, Kris’s Edwin was remote, impassive around his children. It’s unclear if he even recognizes them. But when they sing to him, he wakes up. The hymn connects him not only to his children but also to himself, if only for an instant.

The scene is fragile, beautiful. Everyone is moved by the sweetness of the song and by Kris’s vulnerability. His charisma lends the scene a resonance unlike the one I experienced forty years ago. That visit felt dark, hopeless. We sat in a squalid parlor. A shriveled Edwin—he was fifty and looked one hundred—shook, smoked Camels, and cried when his children sang. I didn’t sense connection in his tears. To my young mind, it was a first glimpse into the heart of the America that had created Blaze Foley—its music, its religion, its fractured love.

That past no longer exists, except as music and memory. And if I’ve learned anything from Blaze Foley, it’s that memory is like a thought: it weighs nothing.

January 7, 2017

Village Studios

The Tree House

A rush of equipment into the woods. Finally, we are filming in the tree house! These scenes, coming at the end of shooting, feel like a reward for all our hard work, a shared adventure before we disband. But there is still so much to do. I notice a medic is onboard now. Blaze and I did fall out of the original tree house on occasion, so maybe her presence is warranted.

This tree house sits perched on a high hill as if dropped there by a flood. You have to look up, up the hill for it. It’s bigger than our tree house was, brighter too.

The making of Blaze has constantly demanded that I abandon what I think of as real and enter the envisioned world these artists have created. At the same time, the creators yearn for authenticity, fired by the desire to make their invented world as believable as it can be.

Frankly, it’s a relief to surrender to it. That past no longer exists, except as music and memory. And if I’ve learned anything from Blaze Foley, it’s that memory is like a thought: it weighs nothing. You can’t even hold it in your hand. And these particular memories are forty years old. They’ve been altered in my mind by time and emotion and more time. The only real constant is how I feel about Blaze and the life we lived together.

The first night of filming in the tree house, I was freezing. Ethan says we have to embrace the weather. And if we’re lucky—it is Louisiana, after all—tomorrow promises to warm up, so we may get several seasons of tree house life on film. But for tonight, there’s a fire in the woodstove, candles, and kerosene lamps giving off an amber glow. The tree house feels lived-in and loved.

Just before the camera rolls, Alia jumps up, finds me behind the monitor, and hugs me. She has come to thank me, I think, but also to receive the passage of the story—and the love—from me to her, from Sybil to Alia, and Sybil to Sybil.

It’s so cold in the tree house that when Blaze and Sybil kiss, their breath mingles whitely. “I’ve never seen this in a movie before,” Ethan cries with delight, opening the door to make it colder, breathier. The crew watches me watching Alia. What really happened to us in that tree house? I think about the seeds that got planted there, the songs that grew from them, and what they have become.

Sybil Rosen lives in rural Georgia. She is the author of Riding the Dog, a Blaze Foley–inspired collection of short stories, which was released in 2015.

- More About:

- Music

- Film & TV

- Books

- Ethan Hawke