Featured in the Houston City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in Houston with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the Houston City Guide

The Undertaker is not from Texas.

Ostensibly a supernatural being—a nearly seven-foot-tall, three-hundred-pound goth Western funeral director in a black Stetson, black duster, and eye makeup—the legendary World Wrestling Entertainment character is from “Death Valley.” Not Death Valley, California, but, y’know . . . hell. “REST. IN. PEACE,” he’d boom to each opponent in the ring, both before and after they’d been vanquished, rolling his eyes back in his head.

Except the Undertaker is also a guy named Mark Calaway. He’s from Houston, played college basketball in Fort Worth, and started his wrestling career—like nearly all the Texas greats—at the Sportatorium in Dallas. He’s lived in Austin since 2004 and is a massive Dallas Cowboys and University of Texas football fan. He swears by Lockhart barbecue (“I get the meat sweats really quick”) and was addicted to Diet Dr Pepper until quitting cold turkey two years ago. His go-to cap and T-shirt choices—“Don’t Tread On Me” and the Blue Lives Matter logo—also suggest that he could someday hold elected office in this state.

But for thirty years, his job was not to let you know that stuff, with very few exceptions. Even as wrestling became increasingly open (and self-referential) about real life versus “kayfabe,” the man behind the Undertaker remained shrouded.

“The character, that was all you got,” says Calaway, whose outside-the-ring voice has a modest but recognizably Texas lilt. “And that was due to what I thought was best for business. I was fully committed to being Undertaker, so I did everything that I could to always present that.”

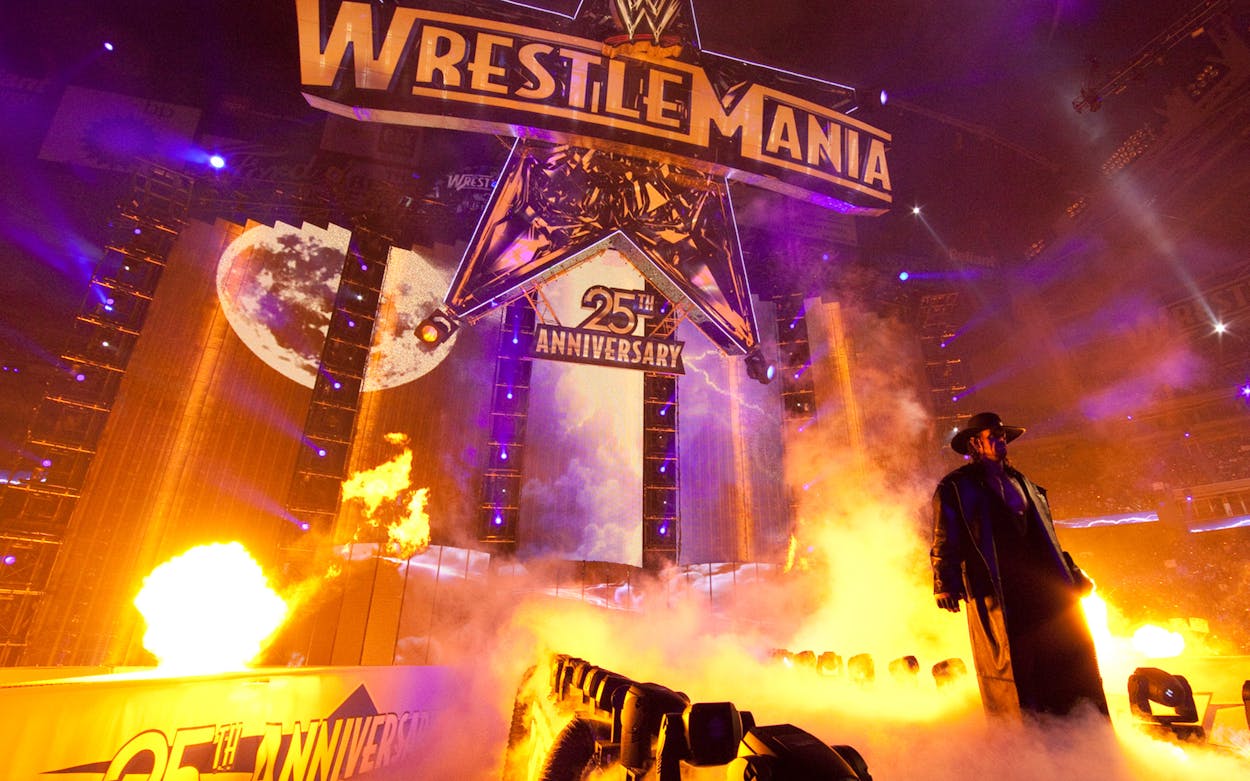

On Friday, WWE will put a cap on that commitment by inducting the Undertaker—and Calaway—into its Hall of Fame in a ceremony during Friday Night Smackdown at the American Airlines Center in Dallas. The Smackdown show is also the prelude to WrestleMania 38, which is Saturday and Sunday at Arlington’s AT&T Stadium.

Wrestling icon Ric Flair has called the Undertaker “the greatest character in the history of the business,” but Calaway’s achievement also transcends “sports entertainment.” As an athlete—yes, professional wrestling’s outcomes may be predetermined, but it’s still a sport of strength and skill—the 57-year-old, who retired from the ring in November of 2020, kept at it longer than Gordie Howe (52), George Foreman (48), and Nolan Ryan (46), with the scars and surgeries to prove it. And if you’d rather call him an actor, that puts the Undertaker among the longest-running characters in television history, right up there with Bart Simpson and Scooby Doo. The Undertaker made his first appearance at Survivor Series (in what was then called the WWF) on November 22, 1990, while the first full episode of The Simpsons aired just under a year before that (December 17, 1989). And yes, it’s fair to say the Undertaker’s just a little bit cartoonish—so long as he’s not standing next to you.

Whereas such wrestlers as Stone Cold Steve Austin (who’s returning to the squared circle for the first time in nineteen years at WrestleMania), Dusty Rhodes, and “Texas Tornado” Kerry Von Erich crafted characters that were as professionally Texan as could be, Calaway happened to find himself on another path.

“Look, I’m that guy,” he says. “I am Texan through and through. To people from outside of the state, I’m probably an obnoxious Texan. I’m just proud of my state and where I’m from. But it didn’t really work for the Undertaker. ‘From Tomball, Texas’ just doesn’t have that same feel to it.”

Calaway first fell in love with wrestling as a kid in northwest Houston (“Kind of between Ella and T. C. Jester”), where he was sometimes able to catch the occasional live card put on by Paul Boesch’s Houston Wrestling promotion at Sam Houston Coliseum. He was also always tall, and he resisted people telling him he had to play football, though his preference for basketball came to feel inevitable once he shot up to six nine.

Calaway began his college hoops career at Angelina College in Lufkin, then transferred to Houston’s University of St. Thomas, which in 1984 was restarting basketball from scratch and enticed him and other recruits with the promise of in-season tournament trips to Florida and Hawaii. But the revival didn’t take, and Calaway wound up playing at Texas Wesleyan for the 1985–86 season. He describes his game as “a Rick Mahorn type,” often with more points scored than minutes played thanks to all the fouls he picked up—not all of which, he says, were fair. “I always looked bigger than everybody. I would just bump into people and they’d fall down. They were flopping before flopping was cool.”

But the whole time he was on the hardwood, Calaway was also still in love with wrestling. After just one year in Fort Worth, he gave up both basketball and college, much to the chagrin of his father, Frank, a printing press coordinator at the Houston Post. The big redhead wanted to chase his dream, and he was willing to toil and suffer for it. He began parking himself outside the Sportatorium each Wednesday, knowing that was the day when the famous Von Erich family promotion, World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW), had its booking meetings. It was also payday for wrestlers, managers, and referees.

But week after week, this six-nine behemoth was ignored.

“The only person who would ever really speak to me was the referee Bronko Lubich,” he remembers. “It was kind of like, ‘Oh, you’re here again, kid?’

“ ‘Yes, sir, Mr. Lubich. I was hoping maybe today I would get to talk to somebody.’

“ ‘Good luck!’ And he would disappear into his office.”

Calaway says he did that for eight months, and was about ready to give up and go find another promotion, when Fritz Von Erich turned up for the first time. The patriarch of Texas wrestling, whose son David had died in Tokyo a few years earlier, stopped and gave Calaway a once-over before entering the building—without so much as a “hello.” But from outside, Calaway could hear Fritz and Lubich talking.

“I could hear him asking Bronco, ‘Who’s that kid out there?’ ” Calaway recalls. “And Bronco was like, ‘He’s been coming for months. He’s just trying to get booked.’ And that’s when I heard him say it. He goes: ‘That kid looks a lot like David. Let’s book him Friday night.’

“And boom, Friday night, I’m in the ring with Bruiser Brody. That was my break.”

Brody “beat the crap out of me pretty good,” says Calaway, who was dubbed “Texas Red” for that first match. But the older brawler—a former West Texas State football player—also gave Calaway advice, and Brody continued helping him down the line. It’s a role the Undertaker would go on to play with wrestlers new to WWE. In Undertaker: The Last Ride, the company’s admittedly unobjective 2020 docuseries about Calaway, his colleagues talk about him the way Texas singer-songwriters talk about Guy Clark or Townes Van Zandt: a wrestler’s wrestler. “The bar for respect is the Undertaker, and everybody else—down here,” WWE star turned Hollywood star John Cena said, holding his hand low to punctuate the point.

Calaway’s early years also included the personas Master of Pain and the Punisher. As the Punisher, he held the Texas Heavyweight Championship for a mere two weeks in 1989 before Kerry Von Erich took the belt. A blond guy then known as Steve Williams also came up through the ranks around this time.

Calaway then moved on to World Championship Wrestling (WCW), where fellow Texan Terry Funk gave him the name “Mean” Mark Callous. But the WWF/WWE is where his career really took off.

Also known as “the Phenom,” Undertaker was unusually athletic for his size, and among other wrestlers, he was renowned for being able to support and set up other performers, win or lose. He was an ostensibly villainous character who became too popular to be anything but a baby face (a good guy), if still, of course, an antihero (and as an ultimately gimmicky and deliberately slow-paced wrestler, he also had his detractors). Facing him was a rite of passage for almost any WWE star, and his signature event was WrestleMania, the company’s biggest annual event. Between 1991 and 2014 the Undertaker went 21–0 at ’Mania, a streak that ended with a legitimately surprising loss to former NCAA wrestling champion Brock Lesnar.

By 2017 Calaway was pretty much only performing at WrestleMania, with an annual ritual of recovering from injuries and surgery, training all over again, and showing up for one big match. That’s when he began filming The Last Ride, and also when he started breaking character (including by doing interviews). It was both a symbolic and a necessary change—a way to force himself to accept that he was nearing the end. With more distance from the Undertaker, he says, “I knew it was going to be easier for me to hang up the hat and coat.”

At times The Last Ride played like an episode of Jackass, as a document of what wrestling does to one’s body (incidentally, Johnny Knoxville will also be at WrestleMania this weekend). There are multiple shots of ice packs and back braces and syringes, and even a bit of operating-room hip surgery gore. “People have no idea how much pain he’s in,” Calaway’s wife, Michelle McCool (who was also a WWE wrestler), said in the series.

More than a few of the Undertaker’s peers have fallen victim to the darkest side of wrestling—debilitating injuries, painkiller addiction, early death. The wrestler Scott Hall died just two weeks ago, at 63, while Calaway’s peer Triple H, who’s also a WWE executive, retired in March at 52 due to heart problems. That’s one thing about wrestling—the outcome may be planned, but the danger is always real.

“The reality is that within any given match, you’re two inches away from something really catastrophic happening at any given time,” Calaway says. “And then when you couple that with the amount of events that are done, it just kind of multiplies exponentially.

“But, you know that when you get in. It’s part of the price you pay to do what you love.”

The past two years are the first in a long time that Calaway hasn’t had to have some kind of operation—though he had plans to see a doctor in Dallas this week to assess the overall condition of his knees. If it takes replacements to keep him hunting and fishing and chasing his kids around, so be it. “I’m old for a wrestler, but I’m a relatively young man,” he says.

While the Undertaker reportedly remains under contract with WWE until 2034 (an interactive Halloween special for Netflix, Escape The Undertaker, was his most recent effort) and will surely pop into some story lines, the Hall of Famer is mostly ready to enjoy retirement and family. He expects to be out looking for turkeys, which he can already hear from his place outside Austin, after WrestleMania. He was the honorary pace car driver at last week’s NASCAR race at Circuit of the Americas, and he also loves to be around the Longhorns—a feeling the team reciprocates.

Only one thing seems to be missing for a guy whose body has its share of ink, both in and out of character: a Texas-themed tattoo. Having already had so many—and having had so many needles stuck in him to numb the pain of wrestling—Calaway jokes that he may be too “too soft” to endure it now.

“But I do need to get some representation,” he says. “It would be a safe bet to think that I will have the state of Texas on my body somewhere before 2022’s over with.”