In a small Texas town better known for its twice-yearly antiques fair, the Round Top Festival Institute looks ardently tranquil, tucked off Texas Highway 237 behind a thick curtain of trees and a long, white Chippendale fence. It’s not uncommon for folks driving by to roll down their windows and ask anyone who might be walking around, “What is this place?”

James Dick, the classical pianist who founded the Institute 51 years ago, loves how the inflection of that question changes, depending on who’s asking it. “Sometimes, it’s ‘What is this place?’ Sometimes, it’s ‘What is this place?’” he told me. Festival Hill, as it is commonly called, has always been both a location and a state of mind. “I never had the idea of it being just ordinary,” said Dick, without a hint of bluster in his proper Kansas accent.

In short, it’s a 210-acre sanctuary where architecture, fine arts, green space, and history are integrated into a “musical landscape” that’s arranged—like a score—to evoke a sense of form, movement, and color. The architectural vernacular, which is distinctive, to say the least, fancifully blends Old World European, Victorian, Medieval, and Czech-German-Texas influences. More than half of the nine buildings, which include artist residences, are historical structures that have been radically transformed. Dick and the late Richard R. Royall V, Festival Hill’s longtime managing director, never saw a building they couldn’t embellish with architectural antiques, handcrafted woodwork, and a whimsical roof statement. The campus centerpiece, a jaw-dropping concert hall that seats one thousand, took 27 years to complete. Ancient-looking stone follies define the many water features (including a grotto, multiple fountains, and a manmade lake fed by a natural creek) and expansive gardens that were designed and long tended by famous herbalists Madalene Hill and Gwen Barkley.

Festival Hill has events throughout the year, but summer is when it sings and why it exists, drawing crowds of classical music aficionados and longtime patrons. During six weeks each June and July, the Round Top Music Festival offers an educational and performance program that’s comparable to the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer academy at Tanglewood and the Aspen Music Festival. The big difference is that in spite of being in Texas, this festival is purposefully smaller than its peers. All of its students receive scholarships and they perform together as the Texas Festival Orchestra. “I wanted a human scale,” Dick said. Still, the numbers have added up to an impressive list of more than three thousand alumni who include principal players of many of the world’s top orchestras, some of whom have returned as faculty.

After a two-year pandemic hiatus, the festival is back in full swing this year with 87 students (selected from 450 applicants) and a rotating faculty of 42 distinguished international musicians. All performances are open to the public, including three paid concerts each Saturday and free weekday master classes. Faculty generally perform chamber music in the afternoons. Programs devoted to Mozart and César Franck, plus recitals by Grammy-nominated flutist Carol Wincenc and the renowned violinist Guillaume Sutre and harpist Kyunghee Kim-Sutre, are highlights this season. Dallas native Michelle Merrill, up-and-coming Argentinean Alex Amsel (assistant conductor of the Fort Worth Symphony), New York’s Dongmin Kim, and Pacific Symphony music director Carl St. Clair lead this summer’s remaining Texas Festival Orchestra concerts. (Performances are ongoing through July 17.)

I’ve known Dick for several years now, and each time I ask for a meeting he invites me to a quiet lunch in the basement dining room at Menke House, where Festival Hill’s small staff receive a comforting lunch daily, year-round, prepared by an in-house chef. Dick, who will be 82 this month, walks to Menke House from his apartment in the staff quarters at Clayton House. He is perpetually busy but rarely appears rushed as he heads to the biggest table and sits under a bay window filled with leggy houseplants. Dick can look intense when he performs, hunching his shoulders over the piano keys as if he is willing the emotion out of them. Offstage, he is humble and approachable, neat and unfussy in his khaki slacks and plaid button-downs.

Festival Hill at Fifty, veteran Houston music critic Carl Cunninham’s history of the enterprise, fills 374 pages, but I wanted to know how on earth Dick dreamed up the place. “Obviously, there’s no small answer,” he said. “But there’s a big answer: it’s a lot of wonderful people. Also one’s own grit and determination. My Aunt Ava took a newspaper called The Grit. I was a little kid but I thought, what an interesting word that is. It stayed with me.” He laughed, the wizened chuckle of someone with age and experience, navigating a meadow of memories as he spoke.

When Dick first saw Round Top in 1968, his career as a concert pianist was just beginning. He had earned a music degree from the University of Texas, spent two years in London on a Fulbright scholarship, made the finals of several major international piano competitions, and was performing around the the country. Philanthropist Ima Hogg, a pianist herself, had befriended him during his student days and invited him to perform during the grand opening of the barn she converted into an Elizabethan-style theater and gave to the university. While the barn was home to UT’s Shakespeare at Winedale program, Dick saw the potential for a summer music festival too, akin to those he’d seen across Europe.

He impressed not just Hogg but other Texas grand dames who stepped up to support Festival Hill. Valuing intellectual musicianship over “the arbitrariness of virtuosity,” Dick insisted on a level of teaching he didn’t see many other places. He traces his artistic lineage all the way to Beethoven, who taught Carl Czerny; Czerny taught Theodor Leschetizky; Leschetizky taught Artur Schnabel; and Schnabel taught both of his teachers, Dallies France (at UT) and Clifford Curzon (in London). The hundreds of students Dick has taught over the years have continued that legacy.

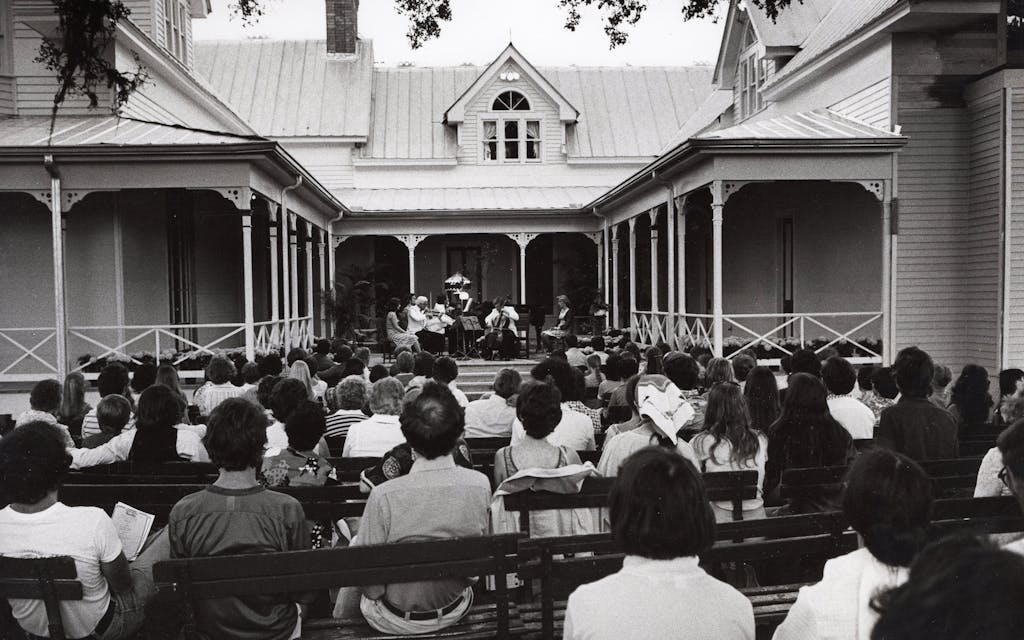

His first Piano Festival Workshop was a two-week program for ten participants, with concerts in the barn, on porches, and in other historic buildings in Round Top, in 1971. Because the piano repertoire naturally extended into chamber and orchestral works, the festival grew. “Music is the whole teller; the whole instrument of how we built this place,” Dick said. “It told us what to do: how to expand and when to expand and how to perhaps go about it. . . . Even when it was just pianists, I wanted it to be of some value. It just has to be. You can’t work with great music and not be responsible.”

The James Dick Foundation for the Arts bought its first plot of land in 1973—six historic but decrepit acres that had become the town dump. Weeds nearly covered the lone building; a low-slung schoolhouse built in 1953 that provided practice rooms. Dick was perhaps more intrigued by the surrounding live oaks, which were hundreds of years old. As the campus grew, he added 24,000 more trees—his other great love. Dick and Royall bought and moved an abandoned, circa-1885 house from La Grange to create Festival Hill’s first staff and artist residence. Never thinking small, they expanded the one-story structure now known as Clayton House into two, with eleven bedrooms, nine and a half baths, three parlors, a functioning kitchen, fireplaces on both floors, and a courtyard. Everything else they would build at Festival Hill would feature Texas-inspired architecture, designs that celebrated music, and as many repurposed materials as possible. (They were way ahead of creative reuse trends.) Menke House, built in 1902, was moved from Hempstead. A circa-1883 church from La Grange became the Edythe Bates Old Chapel. Dick and Royall filled their buildings with antique furnishings, architectural remnants, and historical archives, much of it donated. They usually had too many of their own ideas to hire an architect. “We would go out and draw things up in the parking lot or the sand, and say, what would this look like?” Dick recalled. They had “great arguments,” he said, but usually came around to agreeing.

Meanwhile, the summer concerts went on, outdoors, on a large mobile stage. For patrons as well as musicians, sticking with Festival Hill became an act of faith that might not have endured without world-class performers and music. June bugs bounced into grand piano strings and flew into trumpets. Cicadas and crickets accompanied the percussion. Heat and humidity played havoc with precious instruments. Sudden rainstorms turned the seating area into a mud pit.

Dick and Royall’s crowning achievement, Festival Concert Hall, took longer to construct than any other Texas building I know of. They broke ground on it in 1980; when it finally got a roof in 1983, Festival Hill’s mobile stage was moved inside, although the space wouldn’t be fully enclosed and air-conditioned for four more years. Then came two decades of finish work to create an interior as ornate as any of Europe’s great nineteenth-century concert halls, featuring a symphony of woodwork by local carpenters whose instruments were routers, jigsaws, chisels, hammers, sanders, and patience.

When it was finally finished in 2007, Festival Concert Hall had five miles of molding; a soaring ceiling with a massive star and many octagons; side boxes decorated with gothic tracery and diamond patterns; a stage that suggests a royal library; and galleries holding several historical collections. Every detail and fixture has a meaningful reference or provenance.

Another marvel reveals itself when the music begins: exceptional acoustics. The woodwork isn’t just decorative. “Wood is the greatest purveyor for sound,” Dick said. “Real wood, not just veneer, which some concert halls put up.” Early on, an acoustician told him and Royall the wood should be broken up, so sound would reverberate through and against it. They tweaked the design themselves for years, listening hard during summer concerts when construction was paused for the festival. An eighteen-foot attic above the ceiling and a center aisle between the seats contribute to the aural magic. “You’re kind of sitting in a huge instrument,” Dick said. “I like the idea that we took time. I’ll go out on a limb to say this: I think we built one of the finest concert halls in this country.”

Dick still challenges himself musically, favoring the oldest of Festival Hill’s five grand pianos—an instrument that survived the outdoor years and has been rebuilt several times. He ended his recital last March with Beethoven’s demanding “Appassionata” Sonata. He’ll finish this summer’s festival with Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini.

An unfinished piece of campus development troubles him more: one last building, west of the concert hall, with practice rooms, technically up-to-date conference facilities and a library extension. This time, he won’t start until all the funds are secured. Before Royall died in 2019, the foundation received a grant of $700,000—half of the cost of the project at the time. Now the cost has risen to $2.5 million.

As others began to join us at the Menke Hall table, Dick grew philosophical. “To have a place like this you’ve got to have, obviously, a real business sense, but one that isn’t just an overcommercialization of things,” he said. “Everybody seems to think musicians have such an inability to add two and two. Ever since I was nine, I’ve always had a job. And I’ve saved money all my life. I have a real interest in seeing how things prosper and develop.”

Making a go of Festival Hill took two personalities, suggested Pat Johnson, a longtime staffer. “Jimmy is the creative, the dreamer. Richard had a way of being the balance, setting it up, getting connections and money. He is pretty missed by all of us.”

Dick knows he won’t be around forever, either. Festival Hill has had a succession plan and committee since 2017, but he is not ready to hand over the reins. “I like to get things done myself,” he said. “I’m never planning to retire. Never. Richard and I were given permanent, lifelong positions on the board, and I intend to fulfill that.” When it does happen, he wants his successor to be a longtime faculty member or distinguished alum who has the same spirit, soul, and concerns as he does. “You asked early on, why did the festival need to be educational? That’s gotta be part of it,” he said, “where you are and what the place means. It’s not just another place. It has its own purpose, which has got to be fulfilled and continued.”

- More About:

- Music