On August 7, Michael Hernandez was fed up. That morning, the pitmaster glanced through the window as two inspectors from the Texas Department of Agriculture pulled up to his restaurant, Hays Co. Bar-B-Que, in San Marcos. It was about an hour before the business’s 11 a.m. opening time, and Hernandez was in a meeting. The inspectors walked in the unlocked front door to inspect the scales he uses to weigh his barbecue, he says. Hernandez cut his meeting short and found them in his kitchen. His temper flared. “Get out of my establishment,” he told them. According to Hernandez, the inspectors looked at each other, and then went back to their truck. He says they then returned with a written warning for Hernandez about delinquency on his renewal fee, and told him they were just the messengers. “Here’s my message: tell Sid that I ain’t paying a damn thing,” he said.

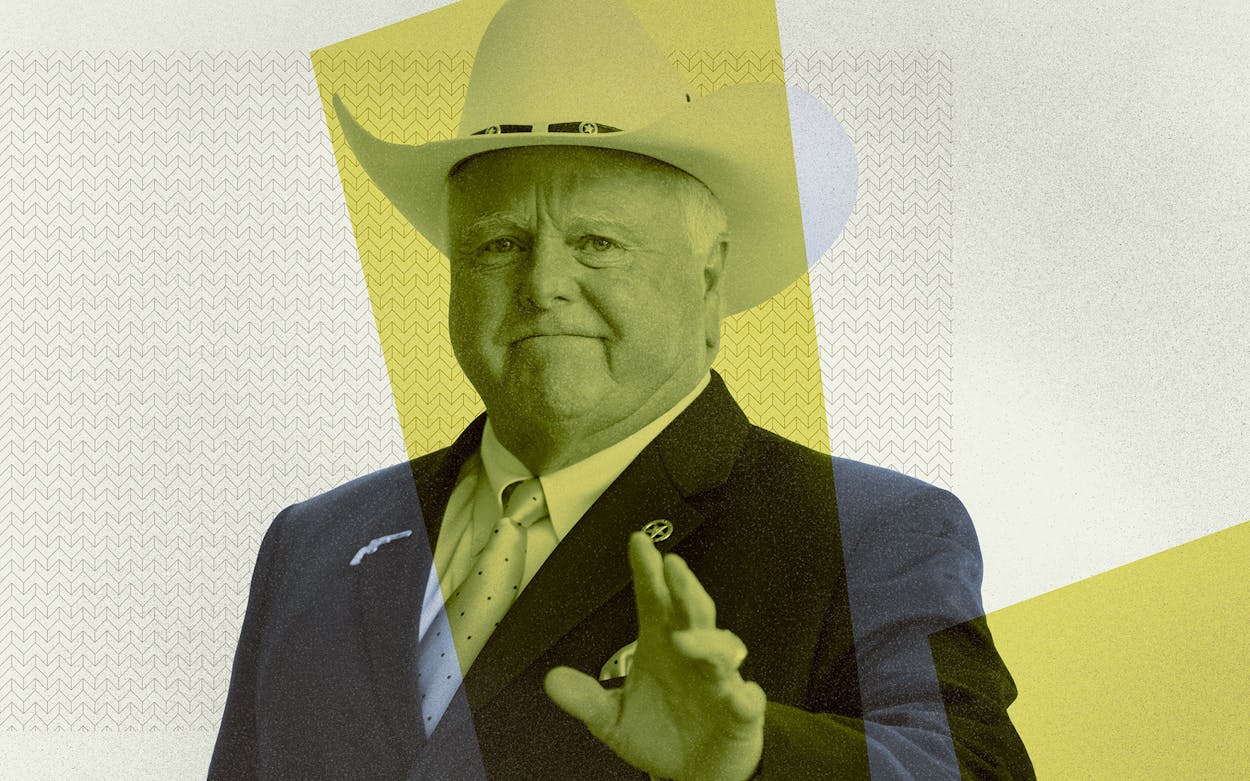

Hernandez was referring to state agriculture commissioner Sid Miller, who has proven himself to be obsessed with the scales inside barbecue joints. The Texas Department of Agriculture had ramped up inspections on barbecue joint scales as part of Operation Maverick back in 2015, but they were removed from the department’s purview after the Barbecue Bill went into effect in September 2017—or so everyone outside of TDA thought. However, even after being repeatedly told the service is no longer required, Miller says his duty to protect the barbecue consumer won’t allow him let to go of barbecue scale enforcement.

The problem comes down to two words: “on premises.” After the legislature two years ago overwhelming passed the Barbecue Bill, which was designed to exempt barbecue joints, yogurt shops, and other establishments weighing food for immediate consumption from inspection, Section 13.1002 was added to the Agriculture Code. It reads: “Notwithstanding any other law, a commercial weighing or measuring device that is exclusively used to weigh food sold for immediate consumption is exempt” from the need for registration fees and inspections from the TDA. Implementing that directive from the legislature was the responsibility of TDA, which left Section 13.1002 alone but added new definitions for “immediate consumption” elsewhere in the Agriculture Code. One definition reads that an exempted scale is “a scale exclusively used to weigh food sold for immediate consumption on premises.”

In other words, the TDA was telling barbecue joint owners that if they sold any barbecue to go, they still had to pay their yearly registrations of $35 per scale and be subject to random inspections. The Texas Restaurant Association, which had supported the Barbecue Bill, cried foul, along with 45 Texas legislators who signed a letter to Miller urging him to change the new rule to align with the intent of the legislature. In response, Miller sought clarification on the rule’s wording from Texas’s attorney general, Ken Paxton. Miller received a response from Paxton in April:

The language of the statute [as written by TDA] requires that the vendor sell food that a consumer can eat immediately, but it does not mandate where or when the purchaser will eat that food. Nor does it require that the seller provide a space for the consumer to eat. On the other hand, the Department’s rules require actual consumption of the food on the premises, placing additional conditions on the buyer and seller in order for a device to be exempt from Department regulation.

In Paxton’s non-binding opinion, Miller’s interpretation was an overreach. Pitmasters, including Hernandez, were relieved. He admits he received a registration renewal letter for his scales from TDA a few months before the surprise inspection, but mistakenly thought that Paxton’s directive meant the issue was over. He was wrong.

“Nothing has changed,” TDA spokesman Mark Loeffler wrote in late June in response to Paxton’s directive. “The Attorney General’s letter is non-binding but has been thoroughly reviewed. Our inspectors will continue to do the work they do every day to protect consumers as outlined in TDA rules.” Miller requested the letter from Paxton—and when it didn’t offer the opinion he hoped for, his department ignored it.

The controversial stance may prove problematic for Miller’s re-election campaign.“For the party that wants to get rid of government regulations, it sure seems like they’re piling on,” said Kim Olson, who is running against Miller for ag commissioner in November. “This is what we’re chasing?” she asked. “We’re in a record drought. Eighty counties are in a disaster area. We’re selling off cattle because we don’t have enough hay or grazing fields. We’re in trouble economically, and you’re chasing down barbecue joints?” Part of Olson’s campaign platform is built around helping farmers, whom she says are “living on the edge” because of low commodity prices and trade wars. She says a feud with legislators about barbecue scales wouldn’t be a priority if she’s elected.

Meanwhile, Rebecca Robinson, the communications manager for the Texas Restaurant Association, says the group plans to provide legal resources to any restaurant protesting its citation for violating the TDA’s rule, which likely won’t withstand an imminent legal challenge. According to his letter, Paxton doesn’t believe the courts would side with the TDA: “A court would therefore likely conclude that the [TDA]’s rules implementing section 13.1002 are invalid.”

Miller remains undeterred. “My job is to protect the consumer. I think it sets a dangerous precedent when one industry doesn’t have to use the scale because everybody else will want an exemption, too,” he told the Tyler Morning Telegraph in July. Miller used this same argument last year when he quoted Proverbs in an unsuccessful plea to sway Governor Greg Abbott to veto the bill, and he’s still using it—even after the legislature passed the Barbecue Bill, Abbott signed it into law, the same legislators disagreed with his interpretation of the rule, and Paxton dissented in an opinion that Miller requested.

It’s unclear why Miller is so determined to keep the business of barbecue under his purview. The TDA doesn’t need the money. After hiking fees almost across the board for TDA registrations in 2016, the department brought in far more money than it required to operate. “The [TDA] set its fees at levels that were higher than necessary to recover its costs,” reads an August 2017 report from the state auditor. Specifically, the department took in $6,492,234 more than needed—and even if all 2,000 barbecue joints in Texas registered two scales each, that would provide $140,000 total, only two percent of TDA’s windfall. As for Miller’s rationale about protecting the public from unscrupulous pitmasters, there are already laws against fraud to aid wronged customers, and the TDA’s own records show only seven complaints about barbecue joints between 2013 and 2017. Besides, the legislature has clearly indicated the TDA’s role in inspecting barbecue scales is no longer necessary.

Miller isn’t alone in his stance: Robert Hebner, who leads the Center for Electromechanics at the University of Texas, sided with him in an op-ed for the Waco Tribune-Herald in July. (The same op-ed was also published in three other publications throughout the month.) Hebner, too, went the biblical route, quoting Deuteronomy and warning that barbecue joint owners, if left unchecked, would be forced “to be dishonest to stay in business.”

Until their actions are legally challenged, a contest that Paxton expects TDA to lose, the agency will continue to seek the $35 annual fee for scales. Pitmasters shouldn’t be surprised to find TDA inspection officers showing up at their kitchens, and officials shouldn’t be surprised if they’re met with resistance. Hernandez, for one, was rattled by his argument with inspectors—and resolute in his stance. “I don’t smoke cigarettes, but I went back to the pit, threw some post oak in the firebox, and inhaled,” he said. And if they send a fine his way? “If it’s not the law, I’m not doing it.”

- More About:

- Sid Miller

- Ken Paxton