This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Almost a decade ago, I was working in what is ponderously known as the motion picture industry, which required my presence for a long spell in Los Angeles. I spent my time in script conferences with a movie star who managed to wake up in a different world each day. Sometimes our story took place high in the mountains; other times the scene moved to the desert or to a nonexistent little town that derived its features from the star’s days in movie houses, when he dreamed of working on his draw instead of on his lines. Some days the Indians won, some days the law. This was about to be one of the last cowboy movies America would put up with.

But myth was something I was still interested in. And so, in the evenings, my wife and I would drive out to Chino, where our friend Joe Heim trained cutting horses. His place was very small, a couple of acres maybe, and the horses were penned wherever space could be found. I particularly remember an old oak tree where we used to hang the big festoon of bridles and martingales. Joe lived in a trailer house, did his books on a desk at one end and slept in the other. We worked cattle under the lights, an absolute anomaly in a run-down suburb. Joe is a first-rate hand whose success has since confirmed his originality and independence. But on those warm nights when cattle and horses did things that required decoding, Joe would always begin, “What Buster would do here is . . .” I had never seen Buster Welch, but his attempts to understand an ideal relationship between horsemen and cattle sent ripples anywhere that cows grazed, from Alberta to the Mexican border. It would be many years before I drove into his yard in West Texas.

Buster Welch was born and more or less raised north of Sterling City, Texas, on the divide between the Concho and Colorado rivers. His mother died shortly after he was born, and he was raised by his grandfather, a retired peace officer, and his grandmother on a stock farm in modest self-sufficiency. Buster came from a line of people who had been in Texas since before the Civil War, Tennesseans by origin. Growing up in the Roosevelt years in a part of Texas peculiarly isolated from modern times, Buster was ideally situated to understand and convey the practices of the cowboys of an earlier age to an era rapidly leaving its own mythology. The cutting horse is a sacred link to those times, and its use and performance is closer to the Japanese martial theater than to rodeo. Originally, a cutting horse was used to separate individual cattle for branding or doctoring. From the “brag” horses of those early days has evolved the cutting horse, which refines the principles of stock handling and horsemanship for the purposes of competition.

When Buster was a young boy, his father remarried and moved his wife, her two children, and Buster to Midland, where the father worked as a tank boss for Atlantic Richfield. Buster’s early life in Sterling City and the separation from his grandparents and their own linkage to the glorious past had the net result of turning Buster into a truant from the small poor school he attended, a boy whose dreams were triggered by the herds of cattle that were then trailed past the schoolhouse to the stockyards. He became a youthful bronc buster at the stockyards and was befriended by people like Claude “Big Boy” Whatley, a man so strong he could catch a horse by the tail, take hold of a post, and instruct Buster to let the other horses out of the corral. By the time Buster reached the sixth grade, he had run away a number of times, and at thirteen he had run away for keeps. In making his departure on a cold night, he led a foul old horse named Handsome Harry well away from the house so his family wouldn’t hear the horse bawling when it bucked. From there he went to work for Foy and Leonard Proctor, upright and industrious cowmen who handled as many as 30,000 head of cattle a year. Buster began by breaking broncs, grubbing prickly pear, chopping firewood, wrangling horses, and holding the cut when a big herd was being worked, a lowly job where much can be learned.

When you see Buster’s old-time herd work under the lights in Will Rogers Coliseum or at the Astrodome in Houston, that is where it began. The Proctors are still alive, revered men in their nineties, descendants of trail drovers and Indian fighters. From them, Buster learned to shape large herds of cattle and began the perfection of his minimalist style of cutting horsemanship and cattle ranching in general. He was having to work with horses that “weren’t the kind a man liked to get on.” But as time went on in those early days, he was around some horses that “went on,” including Jesse James, who became the world champion cutting horse. Nevertheless, he probably spent more time applying 62 Smear, a chloroform-based screwworm concoction, to afflicted cattle than to anything more obviously bound for glory.

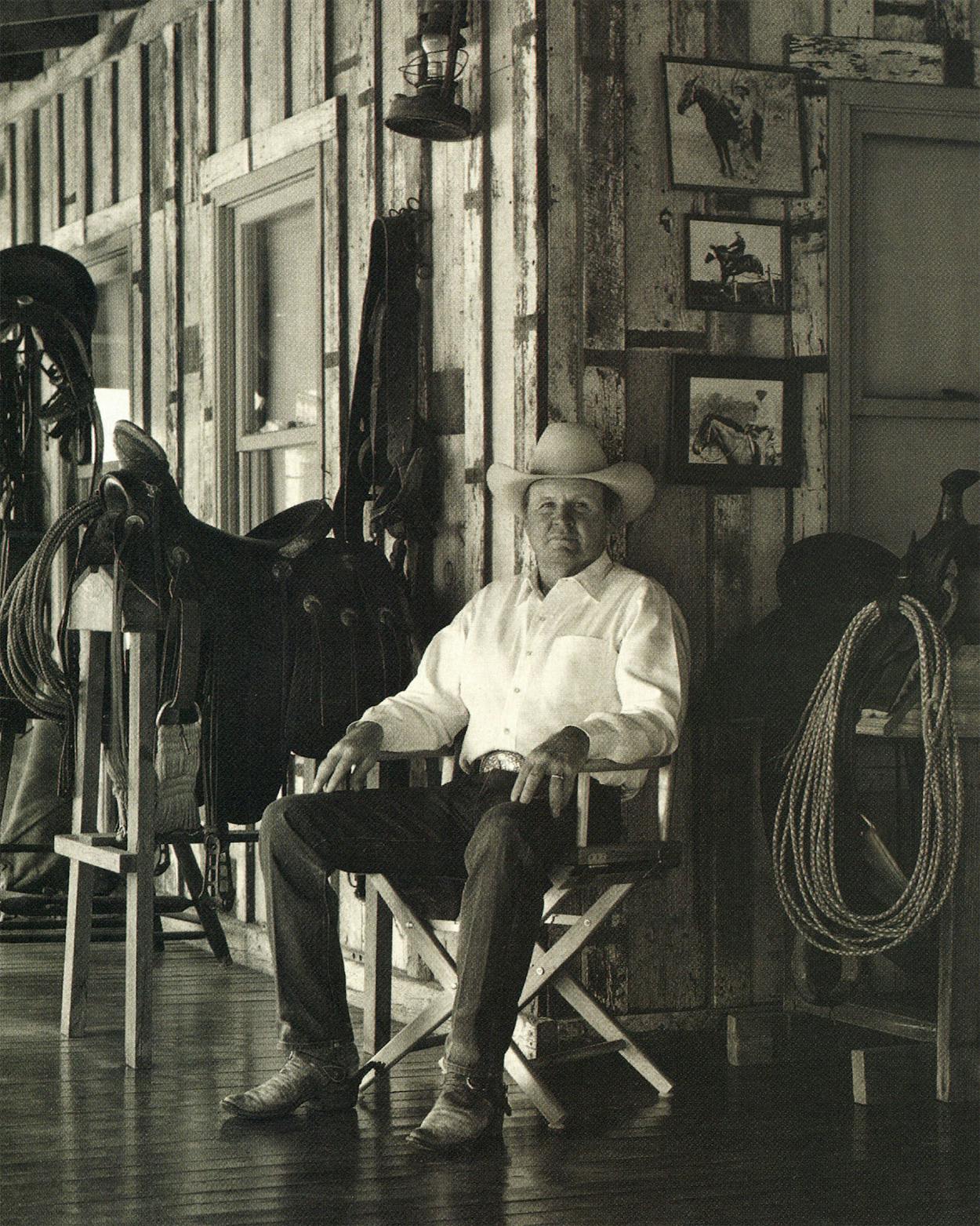

Buster rode the rough string for the storied Four Sixes at and around Guthrie. One of the horses had been through the bronc pen two or three times and was so unrepentant that you had to ride him all day after you topped him off in the morning, relieving yourself down the horse’s shoulder rather than getting off, and at the end of the day, buck down to the end of the reins, turn around, and scare the horse back before he could paw and strike you. But this was an opportunity to be around those good and important cowmen and to work cattle out with the chuck wagon or from the permanent camps on that big ranch. Buster is remembered for his white shirts and for being the only man able to ride the rough string and stay clean. Hands circulated from there to the Matador and the Pitchfork in what amounted to graduate schools for cowboys. Off and on in that period, Buster rode saddle broncs at the casual rodeos of the day, where the prospects for injury far outweighed the opportunity for remuneration. There was certainly in Buster’s life a drive for individuality and authorship in his work that might have been realized earlier if someone had been good enough to leave him a ranch. Even by then ranches were rather strictly in the hands of “sons, sons-in-law, and sons of bitches.” To this day, he sees himself primarily as a rancher; though a balance sheet would certainly profile him fairly strictly as a cutting horse trainer, and that at a time when genuine cutting horses are rarely used in ranch work. In many cases, they not only never see open country; they live the lives of caged birds with an iron routine from box stall to training pen to hot walker to box stall, moving through the seasons of big-purse events to long retirement in breeding programs.

By the time Buster Welch began to establish himself as a horseman, beyond someone who could get the early saddlings on rough stock—that is, came to be able to bring a horse to some degree of finish and refinement—the cutting horse began to come into its own as a contest animal. The adversity of the Texas cattle business had a lot to do with Welch’s career. His plan had always been to use his advantages in training the cutting horse to establish himself in the cow business. And he was well on his way to making that happen in the fifties, running eight hundred cows on leased land, when the drought struck. It ruined many a stouter operator than Buster Welch. In those tough times a horse called Marion’s Girl came into Buster’s life. The weather focused his options, and the mare focused his talent. Buster went on the road with Marion’s Girl and made her the world champion cutting horse that year, 1954. If he ever looked back, he never said so. Capitalizing on events, Buster began to train champion cutting horses at about the rate Westerners, and particularly Texans, were absorbing the concept of formal cutting horse competitions. In those contests, a rider assesses a herd of cattle in order to select cows that will test his horse’s ability and exhibit its virtues. Cattle separated from the herd are extremely resourceful in finding ways to get back. It takes a smart, fast, athletic horse to keep them from succeeding. A true cow horse moves only when the cow moves, matching the cow’s attempts to return to the herd. This would be a standoff, except that the horse is smarter than the cow; the cow finally decides that the move-for-move tactics won’t work anymore. It’s a bad decision because they are the only tactics the cow has; when they fail, the horse has controlled the cow. That cow can now be abandoned by the horse and horseman in the contest situation so that another may be cut. Or in the situation of working a herd on the range, that cow may be sent out of the herd to the cowboys holding the cut.

The National Cutting Horse Association was founded, and the reputations were being made that have since acquired the status of founding fathers. Many of those people have departed the scene in various ways, drifted into an advisory capacity, quit, or died. But Buster Welch, with his unique capacity for refueling, continues to strike paranoia in the hearts of much younger trainers who have made a cottage industry out of wondering what he will do next.

I had been staying in Alabama and was getting ready to go home to Montana. I had managed to catch a ride for my horses from Hernando, Mississippi, to Amarillo, where I wanted to make a cutting, then go on home. This all seemed ideal for paying a visit to Buster at Merkel en route.

Buster greeted me from the screen door of the bunkhouse. The ranch buildings were set among the steadily ascending hills that drew your mind forever outward into the distance. I began to understand how Buster has been able to refuel his imagination while the competition has burned out and fallen behind. There was a hum of purpose here. It was a horseman’s experimental station right in the heart of the range cattle industry.

Buster and I rode the buckboard over the ranch, taking in Texas at this etiolated end of the Edwards Plateau. What is this we have here? The West? The South? The groves of oak trees and small springs, the sparse distribution of cattle on hillsides that seemed bounteous in a restrained sort of way, the deep wagon grooves in rock. We clattered through a dry wash.

“Nobody can ranch as cheap as I can,” said Buster, leaning out over the team to scrutinize it for adjustment; the heavy latigo reins draped familiarly in his hands. “If I have to.” But when we passed an old gouge in the ground, he stopped and said ruefully, “It took the old man that had this place first a lifetime to fill that trash hole up. We haul more than that away every week.” Each year Buster and his wife, Sheila, win hundreds of thousands of dollars riding cutting horses.

Of the hands working on Buster’s ranch, hailing from Texas, Washington, and Australia, there was an array of talent in general cow work. But so far as I could discern, nobody didn’t want to be a cutting horse trainer. There is considerable competition and activity for people interested in cutting horses in Australia, but the country is so vast, especially the cattle country, that well-educated hands go home and basically dry up for lack of seeing one another or for being unable to cope with the mileage necessary to get to cuttings. Nevertheless, such as the situation is, much of the talent in Australia grew up under Buster’s tutelage. Buster is very fond of his Australians and thinks they are like the old-time Texans who took forever to fill the trash hole behind the house. One sees the cowboys at each meal; they have the well-known high spirits, but under Buster’s guidance they are quiet and polite—they rise, introduce themselves, shake hands, and try to be helpful. The reticence and sarcasm of the ill-bred blue-collar horse moron is not found here. In their limited spare time these cowboys make the Saturday night run to town, or they attend Bible classes, or they hole up in the bunkhouse to listen to heavy metal on their ghetto blasters. Buster finds something to like in each of them: one is industrious, another is handy with machinery, another has light hands with a colt, and so on.

Buster has been blessed by continuity and by an enormous pride in his heritage. One of his forebears rode with Fitzhugh Lee and, refusing to surrender when the Confederacy fell, was never heard from again; another fought to defend Vicksburg. Buster’s grandfather was a sheriff in West Texas, still remembered with respect. There are a lot of pictures of his ancestors around the place, weathered, unsmiling Scotch-Irish faces. Buster doesn’t smile for pictures either, though he spends a lot of time smiling or grinning at the idea of it all, the peculiar, delightful purposefulness of life and horses, the rightness of cattle and West Texas, but above all, the perfection and opportunity of today, the very day we have right here.

By poking around and prying among the help, I was able to determine that the orderly world I perceived as Buster’s camp was something of an illusion and that there were many days that began quite unpredictably. In fact, there was the usual disarray of any artist’s mise-en-scène, though we had here, instead of a squalid Parisian atelier, a cattle ranch. But I never questioned that this was an artist’s place.

For example, the round pen. Buster invented its present use. Heretofore, cutting horses not trained on the open range—and those had become exceedingly rare—were trained in square arenas. Buster trained that way. But one day a song insistently went through his head, a song about “a string with no end,” and Buster realized that was what he was looking for, a place where the logic of a cow horse’s motion and stops could go on in continuity as it once did on the open range, a place where walls and corners could never eat a horse and its rider and stop the flow. By moving from a square place of training to a circular one, a more accurate cross section of the range was achieved. A horse could be worked in a round place without getting mentally “burned” by annoying interruptions (corners); the same applied to the rider, and since horse and rider in cutting are almost the same thing, what applied to the goose applied to the gander. The round pen made the world of cutting better; even the cattle kept their vitality and inventiveness longer. But Buster’s search for a place where the movement could be uninterrupted was something of a search for eternity, at least his eternity, which inevitably depends on a horseman tending stock. Just as the Plains Indians might memorialize the buffalo hunt in the beauty of their dancing, the rider on a cutting horse can celebrate the life of the open range forever.

Buster Welch’s horses have a “look,” and this matter of look, of style, is important. The National Cutting Horse Association book on judging cutting horses makes no mention of this; but it is a life-and-death factor. There are “plain” horses, or “vanilla” horses, and there are “good-moving horses,” or “scorpions.” Interestingly enough, if categorization were necessary, Buster’s horses tend to be plain. It is said that it takes a lot of cow to make one of his horses win a big cutting. On the other hand, his cutting horses are plain in the way that Shaker furniture is plain. They are so direct and purposeful that their eloquence of motion can be missed. Furthermore, we may be in the age of the baroque horse, the spectacular, motion-wasteful products of training pens and indoor arenas. Almost no one has the open range background of Buster Welch anymore.

Those who worked cattle for a long time on the open range learned a number of things about the motion of cow horses. A herd of cattle is a tremulous, explosive thing, as anxious to change shapes as a school of fish is. Control is a delicate thing. A horse that runs straight and stops straight doesn’t scare cattle. And a straight-stopping horse won’t fall with you either. Buster Welch’s horses run straight and stop straight. They’re heads-up, alert horses, unlikely to splay out on the floor of the arena and do something meretricious for the tourists. They are horses inspired by the job to be done and not by the ambitions of the rider. Buster has remarked that he would like to win the world championship without ever getting his horse out of a trot. That would make a bleak day for the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce but a bright one for the connoisseur.

There were three or four people hanging around the bunkhouse when we got back. One was the daughter of a friend of mine in the Oklahoma panhandle, there with her new husband. They had all just been to a horse sale in Abilene, where they ran some young horses through. They were in shock. They just sprawled out on the benches in the dogtrot, which was a kind of breezeway, and took in what a rude surprise the price of horses had gotten to be. “Look at it this way,” said Buster. “You don’t have to feed those suckers anymore.” He looked around at the faces. “You are the winners,” he added for emphasis.

Buster is practical. He helped start the futurity for three-year-old horses because the good, broke, open horses lasted so long; the need for trainers was small and even shrinking. He thought it might be good to steal a notion from the automobile industry and build some planned obsolescence into the western cow horse.

It worked. The boom in cutting, the millions in prize money given away annually, is largely spent on the aged-event horses, especially three- and four-year-olds. Syndicates have proliferated, and certified public accountants lead shareholders past the stalls of the assets. This year’s horses spring up and vanish like Cabbage Patch dolls, and the down-the-road open horse is in danger of becoming a thing of the past, an object of salvage. If the finished open horse doesn’t regain its former stature, the ironic effect of large purses for young horses and the concentration of those events in Texas will be to deprive cutting of its national character and to consign it to the minor leagues.

One of the best horses Buster ever trained is a stud named Haida’s Little Pep. When Buster asked me if there was any horse in particular I wanted to ride, I said Haida’s Little Pep. Buster sent a stock trailer over to Sterling City, where the horse was consorting with seventy mostly accepting mares. I couldn’t wait to see the horse whose desire and ability, it had been said, had forced Buster to change his training methods. (He actually leaks some of these rumors himself.) Buster watched the men unload the stallion, in his characteristic position: elbows back, hands slightly clenched, like a man preparing to jump into a swimming pool. Haida’s Little Pep stepped from the trailer and gazed coolly around at us.

We saddled him and went into the arena. “Go ahead and cut you a cow,” said Buster. Two cowboys held a small herd of cattle at one end. My thought was “What? No last-minute instructions?”

I climbed aboard. Here I had a different view of this famous beast: muscle, compact horse muscle; in particular a powerful neck that developed from behind the ears, expanding back toward the saddle to disappear between my knees. The stud stood awaiting some request from me. I didn’t know if, when I touched him with a spur, he was going to squeal and run through the cedar walls of the pen or just hump his back, put his head between his legs, and send me back to Montana. But he just moved off, broke but not broke to death; the cues seemed to mean enough to get him where you were going but none of the flat spins of the ride-’em-and-slide-’em school. Haida’s Little Pep, thus far, felt like a mannerly ranch horse. I headed for the herd.

Once among the cattle, I had a pleasant sensation of the horse moving as requested but not bobbing around trying to pick cattle himself. His deferring to me made me wonder if he was really cooperating in this enterprise at all. As I sorted a last individual, he stood so flat-footed and quiet that I asked myself if he had really mentally returned from the stallion station. I put the reins down. The crossbred steer gazed back at the herd, and when he turned to look at us, Haida’s Little Pep sank slowly on his hocks. When the steer bolted, the horse moved at a speed slightly more rapid than the ability of cattle to think and in four turns removed the steer’s willpower and stopped him. The horse’s movements were hard and sudden but so unwasteful and accurate that he was easy to ride. Because of the way this horse was broke, I began thinking about the problems of working these cattle. I immediately sensed that the horse and I had the same purpose. I’ve been on many other horses that produced no such feeling. There was too much discrepancy between our intentions. We wanted to cut different cattle. They didn’t want to hold and handle cattle; they wanted to chase them. They didn’t want to stop straight; they wanted to round their turns and throw me onto the saddle horn. But this high-powered little stud was correct, flat natural, and well intentioned.

We looked at some old films in Buster’s living room. They were of Marion’s Girl, whom Buster had trained in the fifties, the mare who had done a lot to change the rest of his life. I had long heard about her, but I remember Buster describing her to me for the first time at a cutting on Sweet Grass Creek in Montana. The ranch there was surrounded by a tall, steep bluff covered with bunchgrass and prickly pear; it was maybe a thousand feet high and came down to the floor of the valley at a steep angle. Buster had said that Marion’s Girl would run straight down something like that to head a cow, stop on her rear end, and slide halfway to the bottom before turning around to drive the cow. As all great trainers feel about all great horses, Buster felt that Marion’s Girl had trained him; more explicitly, she had trained him to train the modern cutting horse. At that time most cutting horses kind of ran sideways and never stopped quite straight. Buster considered that a degraded period during which the proper practices of the open range were forgotten. Marion’s Girl, like some avatar from the past, ran hard, stopped straight and hard, and turned through herself without losing ground to cattle.

As I watched the old film, I could see this energetic and passionate mare working in what looked like an old corral. Though she has been dead for many years, the essence of the modern cow horse was there, move after move. In the film Buster looked like a youngster, but he bustled familiarly around with his elbows cocked, ready to dive into the pool.

Are horses smart or dumb?” I asked Buster. “They are very smart,” he said with conviction. “Very intelligent. And if you ask one to do something he was going to do anyway, you hurt his feelings, you insult his intelligence.”

Everyone wants to know what Buster Welch’s secret in training horses is; and that’s it. Only it’s not a secret. All you need to know is what the horse was going to do anyway. But to understand that, it may be necessary to go back forty years and sit next to your bedroll in front of the Scharbauer Hotel in Midland, waiting for some cowman to come pick you up. If you got a day’s work, it might be on a horse that would just love to kill you. It was a far cry from the National Cutting Horse Futurity, but it was the sort of thing Buster began with and lies at the origins of his education as to what horses are going to do anyway.

I stayed in the living room to talk to Sheila Welch while, outside the picture window, horses warmed up in the cedar pen. Sheila is a cool beauty, a fine-boned blonde from Wolf Point, Montana, and a leading interpreter, through her refined horsemanship, of Buster’s training. She is capable of looking better on Buster’s horses than he does and certainly could train a horse herself. Cutting horses move hard and fast enough to make rag dolls of ordinary horsemen, but Sheila goes beyond poise to a kind of serenity. A little bit later, Sheila stood in the pen waiting for someone to give her the big sorrel horse she has used to dispirit the competition for years. When he was brought up, she slipped up into the saddle, eased into the herd, and imperceptibly isolated a single cow in front of her. The horse worked the cow with the signature speed and hard stops; Sheila seemed to float along cooperatively and forcefully at once. But I noticed that in the stops, those places where it is instinctive to grip with one’s leg and where it is preferable not to touch the horse at all, there was a vague jingling sound. What was that vague jingling sound? It was the sound of iron stirrups rattling on Sheila’s boots. Can’t get lighter than that. My own riding came to seem hoggish wallowing, prize-repellent.

At its best, the poetry remains, not in the scared, melodramatic antics of the stunt horses but in the precision of that minority singled out as “cow horses,” sometimes lost in the free-base equine atmosphere of the aged events but sooner or later restored to focus in the years of a good horse’s lifetime.

In training horses, Buster’s advantage is a broader base of information from which to draw. He frequently starts out under a tree at daybreak with a cup of coffee, reading history, fiction, politics, anything that seems to expand his sense of the world he lives in. This may be a compensatory habit from his abbreviated formal education, and it may be an echo of his revered grandfather’s own love of books. In any event, Buster has made of himself far and away the most educated cutting horse trainer there is. In any serious sense, he is vastly more learned than many of his clients, however exalted their stations in life. And apart from the intrinsic merits of his knowledge, there is a place for it in Buster’s work; because an unbroke horse is original unmodeled clay that can be brought to a level of great beauty or else remain in its original muddy form, dully consuming protein with the great mass of living creatures on the planet.

But a cutting horse . . . well, a cutting horse is a work of art.

Thomas McGuane lives in McCloud, Montana. His collection of short stories, To Skin a Cat, was published by E. P. Dutton in 1986.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Horses

- Cowboys

- Abilene