The hamburger belongs everywhere. It is named after a German town and has historically been served with French fries, which actually have their origins in Belgium. You can find one almost anywhere you travel in the world. But with the first bite of a Whataburger one recent Saturday afternoon, I am acutely in Texas. I need both of my hands to wrangle the burger, my sixth in as many days. The orange-and-white-striped bag it comes in features a silhouette of the state. My mind is ready to secede.

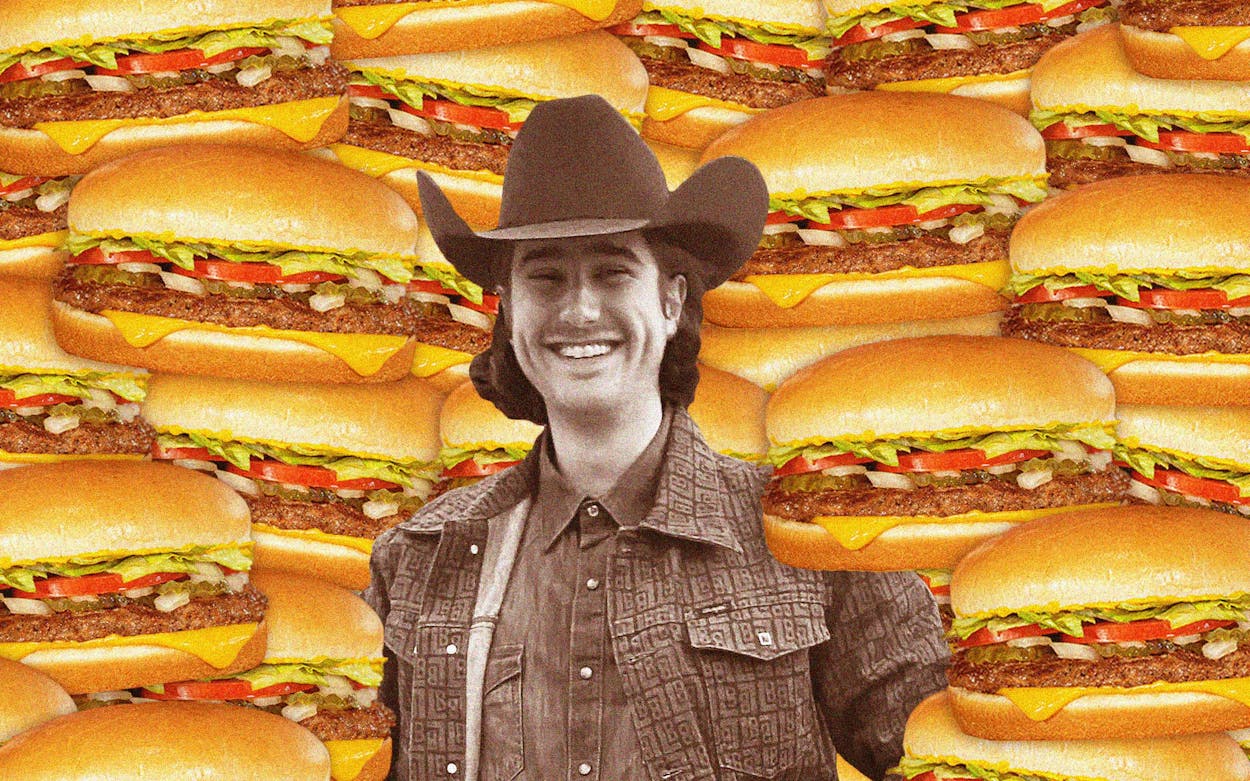

I am nearing the end of a scientific and spiritual inquiry. I am a relatively recent arrival from New York by way of California and am trying to become more Texan, in part by a weeklong immersion in Whataburger. While belief in almost all American institutions, from the feds to the church, is flagging around the country, people still love their local fast-food chains. In the Midwest, Culver’s and Steak ’n Shake reign supreme, and in the mid-Atlantic, Five Guys dominates. They all inspire devotion, but here in Texas, Whataburger inspires something more: a sense of identity. Californians like In-N-Out; to be Texan is to love Whataburger.

My adventure has simple ground rules: all my breakfasts, lunches, and dinners for a week must come from Whataburger, although I can snack on other foods in between. And I can choose any item to eat, but I should try to hit as much of the menu as possible.

While my coworkers pray for my arteries, I am not intimidated. I eat a lot of fast food, particularly McDonald’s. Every week I eat a couple of meals from there at my dining table, beneath an oil painting of the restaurant. Though I found Whataburger unremarkable (not the worst thing a fast-food joint can be) the few times I tried it, my friends have regaled me with halcyon tales of trips there. The restaurant, I’m assured, is a paradise for debauched teenage nights, a panacea for mornings after parties, and the perfect spot for a quick lunch.

On my first of 21 meals, lunch on a Sunday, I’m immediately struck by the waiting: Whataburger, I come to find out, is not so much a drive-through as a park-at restaurant. I wait in a line of cars for twenty minutes for a classic Whataburger with onion rings and an iced tea. When my order finally arrives, my anticipation and appetite have not built so much as atrophied. The enormous burger defies all who would try to consume it while driving, so I take it home with me.

There, I find the meat patty is thin, like a coat of paint on the bun, with a pizza-place salad of toppings crowning the filament of protein. The onion rings offer a welcome reprieve: they are airy, and they aren’t so oniony as to leave me with bad breath. I’m confused, as ever, by Whataburger’s hold on the state. For my second meal, later that night, I return in high spirits. Perhaps I’ve just made the wrong menu choice. I wait in a drive-through lane again for fifteen minutes and opt for a spicy chicken sandwich. It is not spicy enough, but I feel more Texan when I add the Buc-ee’s Ghost Pepper hot sauce I keep at home.

Although one definition of insanity is ordering the same thing twice and expecting a different result, the photo on the menu the next day at lunch (after a breakfast of the satisfying Honey Butter Chicken Biscuit) convinces me this spicy chicken sandwich is going to be the one. I eat it in my office, and it is fine. It leaves me craving Popeyes, and I begin to feel like a carpetbagger, unable to see the Texas Miracle, or perhaps seeing it too clearly and understanding it as a magic trick.

The morning of day three starts off strong with sausage, egg, and cheese on a Jalapeño Cheddar Biscuit, which has been put back on the menu that morning to much fanfare, but by lunch (chicken strips) I have grown weary of my assignment. The fries are legitimately good and are treated like a genuine part of the experience, not an obligation as they are at In-N-Out; the chicken strips taste like, well, chicken. But I haven’t seen the light. My reviews of meals kept in my phone’s Notes app have become monosyllabic: “fine,” “bleh,” and “lol.” I am annoyed that the meals didn’t have the decency to be so bad I’d be inspired to write more.

By day four, I must journey into a wondrous land of imagination. To disrupt the tyranny of salt, I try an apple pie accompanied by fresh apple slices for dinner, and a brownie for breakfast. I resolve to be more deliberate about my menu planning: the joy of arriving at a drive-through line and deciding on the spot will not serve me here. When I seek out my coworkers for relief, everyone suggests I try something different. The Texanist recommends getting double meat on a bacon burger. Another colleague swears by the Buffalo Ranch Chicken Strip Sandwich. Still others proselytize the Jalapeño Cheddar Biscuit, but in a different way than I’ve ordered it.

Eventually, I find my own safe havens. On day five, I find consolation in the one-spice jalapeño-and-cheese burger. On day six, I discover the Patty Melt is one of a kind: the Thousand Island dressing adds a tanginess my taste buds have forgotten, and it is a dish I cannot find approximated at other fast-food chains. By day seven, I have experimented my way to the right condiment. The creamy pepper sauce elevates the chicken strips from a burden to a meal.

I still don’t get the draw of Whataburger, however, until late in the week, when I realize I’ve mistakenly focused on the food and not the Idea of the Food. Throughout my adventure, I invited colleagues to dine with me, but most refused, which I took as a tacit admission of distaste for the chain. Then, one day, I ask one of the bigger Whataburger partisans in our office, who declines my invitation but, in doing so, gives me a breakthrough.

She says she doesn’t like Whataburger, she likes her Whataburger, and she implores me to try a few to make sure I’m not just eating at one of the bad ones. Though I’ve already eaten at three different locations, my coworker’s admonishment confuses me: the appeal of most fast food is that it tastes the same everywhere. But later that day, when I’m at my Whataburger—one near my home—eating with colleagues, I finally get it. The chain’s appeal is not the comfort of conformity but precisely the opposite. Its chief currency is circumstance: the friends you ate it with, the contours of the night that led you there.

I realize I have been doing a kind of parachute journalism by sticking to the drive-through. My colleagues and I share ketchup and trade sauces while discussing the stupid things we used to eat in college. A man hovers near our table and, when our conversation stalls, seizes the opportunity to hit on my friend. Weeks later, I won’t remember what I ate that day, but we’ll still be discussing his failed attempt.

To make better sense of my realization, I talk to Ashley Bean Thornton, a self-described superfan from Waco who made news recently for eating at Whataburger nearly every day for ten years. When she goes on vacation, she plans her hotels around proximity to the chain, and when the restaurants temporarily closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, she even learned to make the Jalapeño Cheddar Biscuits herself. I confess to Thornton my slight shame at feeling so exhausted by the restaurant after only 21 meals, and I ask her what’s kept her coming back for a decade.

Thornton describes her daily meal in religious terms: the “congregation” of folks she sees every morning, “her own little pew” where she sits, how she feels “virtuous” on days she orders apple slices. She tells me of friendships she’s formed with strangers while waiting interminably for her orders: the employee she now bakes Christmas cookies for, the customer who needed a hug after his wife went to prison, the group of older men who talk politics and tease her for her disagreements with them. She barely references the food.

Then she explains what makes a Whataburger ideal: an A-frame build, no TVs or screens, and sturdy furniture that reminds her of home. “Part of what makes it a hometown thing is you can only really get it in your hometown,” Thornton says when dismissing Whataburger locations out of state. “Missing it is part of the beauty of it.”

Ultimately, I’m a man in Texas without a hometown here, and not much of a history to miss anything. But the day I finish my duty, I go to a pool party with friends, and when suddenly the day has passed us by, I’m hungry. Free of my assignment, I rush to Taco Bell, where the meal is delicious, but not quite satisfying. After listening to my friends tell stories about fun nights at Whataburger, I’m still hungry when I’m done.