This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Sunday, August 19

RECORD HEAT GREETS DELEGATES, says the Dallas Morning News, and who can argue? By noon it’s 100 degrees downtown and rising. The Adolphus Hotel sets up a special “port-a-tunnel” that attaches to the car doors of arriving VIPs so they won’t have to step outside. At the DFW Airport, 3000 delegates, 2000 Republican politicians, and 20,000 reporters arrive in a hail of lost luggage. Airport officials request presidential designation as a disaster area, so that luggage can be found.

The mood of the Republicans, smelling victory in the fall, is jubilant; the mood of the press, smelling a no-surprises convention without even gavel-to-gavel TV coverage, is surly. 60 Minutes carries a special one-hour report called “The Other Dallas,” focusing on South Dallas and its problems of huge unemployment, poverty, and poor housing. “The Republicans will see a glittering, prosperous city,” says correspondent Ed Bradley, “but it is here that we have found the Dallas that President Reagan doesn’t want you to see.” NBC and ABC compete with one-hour specials called, respectively, The Hidden Dallas and The Dallas the Republicans Don’t Want You to See.

On Face the Nation an angry Lesley Stahl questions convention welcoming committee chairman David Fox: “Let’s call a spade a spade, Mr. Fox. Isn’t Dallas just a provincial, boring, rich city, yet also the home to stark poverty that convention officials don’t want us to see?” Fox apologizes and promises on the spot to appoint a bipartisan public-private commission to ensure the presence of what he calls responsible protest during the week. Later in the day he appoints former mayor pro tem George Allen, nightclub entrepreneur Philippe Starck, and artist Robert Wade as cochairmen, orders them to meet immediately with business leaders to develop plans.

Among the celebrities spotted by the press at the airport: Julius Bengtsson, globe-trotting hairdresser to Nancy Reagan; cowboy novelist Louis L’Amour; antinuclear activist Helen Caldicott (“Have you ever noticed that the Dallas skyscrapers are shaped like nuclear missiles?”); former president Richard Nixon (“I understood the Russians, and the Russians understood me”); and former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger (“The world situation is very, very grave and very, very complicated. Twenty thousand dollars, please”). Barely noticed in the crowd: a slight man in a tropical suit and sunglasses, carrying a set of orthodontist’s instruments.

Monday, August 20

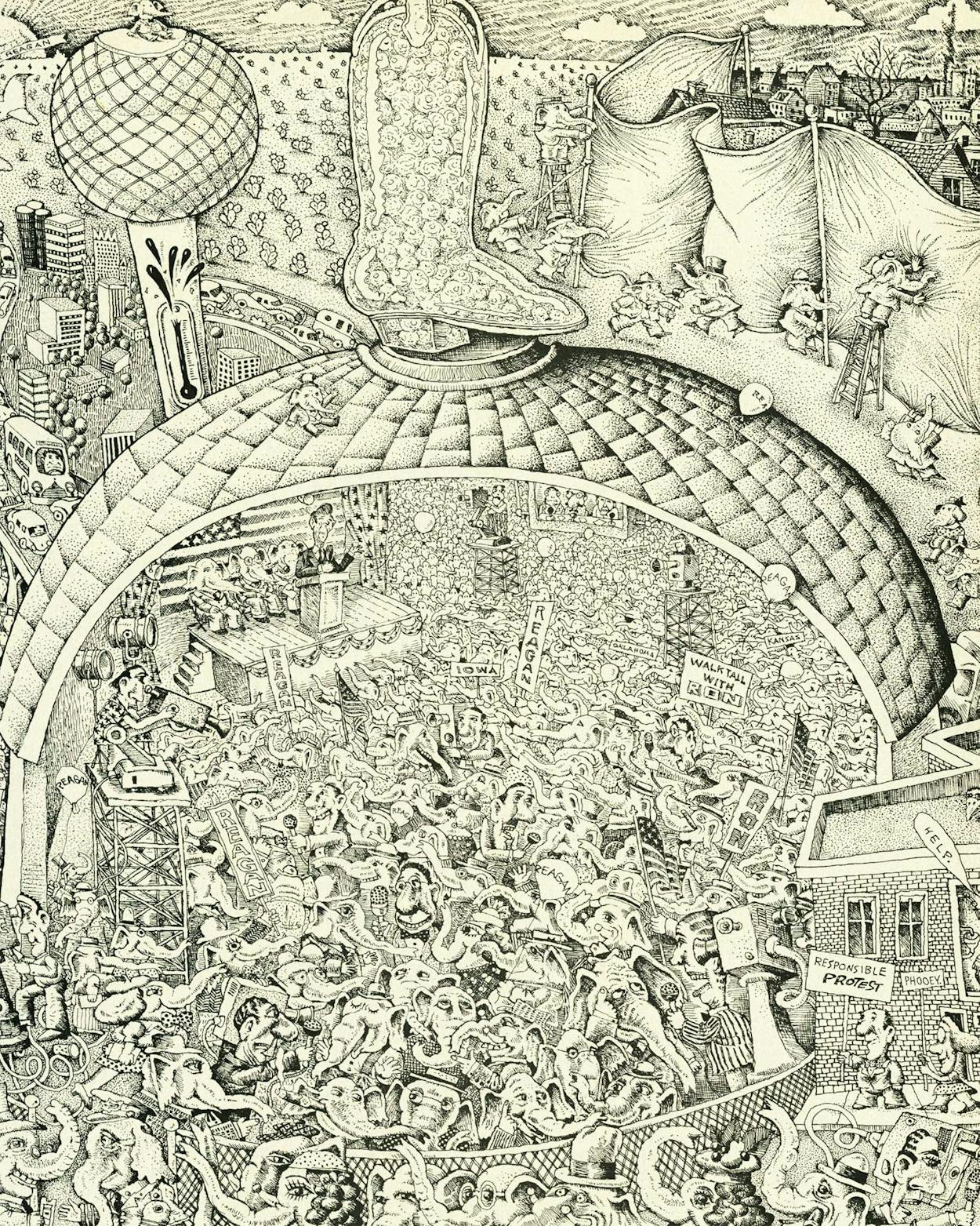

The Dallas Times Herald carries a special report, by a team of seventeen reporters and editors, called “Negativism in the Media: Crisis at the Crossroads.” The Morning News counters with a special pullout section called “International City, Negative Media: A Convention in Conflict.” The bipartisan Commission on Protest (COP), at a prayer breakfast at Prestonwood Country Club, calls for solving “the mess on Capitol Hill” by abolishing single-member congressional districts, electing all 435 members of the House of Representatives at large in November. The Senate would stay unchanged to ensure representation of minority groups. The commission’s plan is to hire one hundred disadvantaged youths at subminimum wage—outfitted in chic wrinkled-look linen suits, courtesy of civic-minded local retailers—to picket the convention Wednesday night; artist Wade will hire a crew and work around the clock to produce a huge sculpture showing 435 heads of cabbage inside a giant Lucite cowboy boot, to symbolize the congressional reform plan.

Vice President Bush and his entourage arrive at Love Field; he holds an impromptu press conference before five hundred waiting reporters, says he is proud to have achieved many historic firsts in his career, including being the youngest pilot in the Navy and, “best of all,” next-in-line to the oldest president.

The convention officially opens with an invocation from the Reverend W. A. Criswell of the First Baptist Church. “Surely the Lord is smiling on this gathering today, and on the good works of this, His favorite president,” Criswell reads, standing under a huge banner that reads, “LET’S FINISH IT OFF, MR. PRESIDENT.” Platform debate begins with brewing controversies on one plank calling for further deep tax cuts to reduce deficits, another putting the country in a state of permanent military alert against the Soviet Union. White House chief of staff James A. Baker III, at a lunch with 750 reporters, calls the proposals ridiculous; New Right leaders Richard Viguerie and Terry Dolan counter by introducing a plank to purge the second Reagan administration of pragmatists. In a dramatic keynote address, U.S. Treasurer Kathryn Ortega calls for “a pragmatic purism” and asks the media to “write about the real gender gap—between Republicans and sissies.”

CBS Evening News, in an unusual move, broadcasts from Southfork ranch, setting of the hit CBS show Dallas, in order, says anchorman Dan Rather, to demonstrate “who has been helped by Reaganomics.” Vice President Bush, invited to 47 North Dallas parties tonight, instead spends the evening as guest caller at Oak Cliff Assembly of God’s bingo night, in an effort to dispel the image of a rich man’s administration. The First Lady arrives at Love Field in Air Force One and, after a session with Bengtsson, speeds via motorcade to bowl at Don Carter’s All Star Lanes West, where it’s league night. “Ronnie and I just love this kind of thing,” she tells reporters. “It’s so basic.”

Back at the convention, Mrs. Reagan rapturously watches a thirty-minute film called Destiny of Greatness, showing highlights of her husband’s presidency. At the Hyatt, the man in the tropical suit quietly checks in under the name “Carlos.”

“Carlos who?” says the registration clerk.

“Just Carlos,” he replies.

Tuesday, August 21

Mayor Starke Taylor, at a breakfast press conference at Bent Tree Country Club, announces the formation of To Defend Dallas, Inc., a “unique public-private partnership” between civic and business leaders aimed at proving to convention visitors that Dallas is a “sophisticated, cosmopolitan world capital,” never dull, not self-satisfied but always questioning. “This organization, and our quick response, proves it,” says the determined mayor. Outside, specially equipped limos wait to take reporters on a tour. First stop: Fort Worth, “so they’ll know what an unsophisticated, provincial city looks like. After that, Dallas ought to look pretty good,” says Taylor. “If they think it’s boring here . . .”

President Reagan, still in Washington, issues a statement praising the New Right leaders as “great Republicans” and says he admires their “gumption.” He also announces he will personally phone them to express his support. Shortly after the call, Viguerie and Dolan formally withdraw their opposition to the platform and to Bush’s renomination as vice president.

Barbara Walters broadcasts an evening special on Dallas leaders, featuring intimate, revealing interviews with former governor Bill Clements (“Do you like you?”), ex-Cowboys star Roger Staubach (“Who is Roger Staubach, anyway?”), and stockbroker Billy Bob Harris (“Those ugly rumors, Billy Bob—are they true?”). The McNeil-Lehrer News Hour broadcasts a four-hour special report called Texas: The Myth . . . and the Reality, featuring wide-ranging Texas experts Dr. Bernard D. “Bud” Weinstein (“The Sun Belt has become the Technology Tank Top”), Rosemary Kent, Joanne Herring, and A. C. Greene (“Anybody who thinks Dallas is provincial probably is not a native Texan and certainly hasn’t met me”).

By day’s end, crisis threatens: during a press tour of “the sewer system that works,” the mood turns ugly, and reporters overturn several of the tour limos. Soon roving bands of reporters, frustrated by what one calls “unconscionably low” rates of news production by the Republicans, begin breaking into leading politicians’ hotel rooms and running away through downtown streets with pilfered briefcases under their arms.

Wednesday, August 22

Long before day’s first light, cameras from all three networks are positioned outside the Convention Center to film the day’s protest activities. Promptly at 7:30 a.m., one hundred disadvantaged youths in linen suits emerge from a prayer breakfast at the Hyatt and form a thin picket line. Convention officials assign a pool of thirty reporters to each marcher; President Reagan issues a statement praising their courage. Placards seen in the picket line: RESTORE THE CONSENSUS; LET OUR LEADERS LEAD; AMERICA, THE COUNTRY THAT WORKS. As the demonstration ends promptly at 8, each protester is made a member of Junior Achievement by Mayor Taylor in a brief, moving ceremony. Officials announce that other protesters will be demonstrating inside a temporary enclosure near Denton, where they have been bused “for their convenience.”

The crisis in the press corps ends abruptly when Vice President Bush fails to show up for a meeting of the Texas delegation and isn’t in his room either. Reporters form a human chain encircling downtown Dallas and announce they’ll force everyone entering and leaving to hold a press conference until the vice president is found. Nancy Reagan cancels a luncheon at the home of oilman Ed Cox honoring the staff of Interview magazine and helping disadvantaged youth; Representative Jack Kemp announces that “it is at these moments that patriots like myself must declare to the president that we stand especially ready to serve him in any way, no matter how arduous.”

The youngest delegate, fourteen-year-old Susie Barger of Minton, Nebraska, interrupts a day-long session of work on her memoirs to declare that she is “of course available to the president in this dark hour.” ABC News broadcasts a three-hour special called George Bush, Pragmatist. Mayor Taylor announces he is confident that through leadership, vision, and God’s help, Bush will be found.

President Reagan lands in Dallas just as he is being unanimously renominated on the first ballot and rushes to the presidential suite at the Anatole, where debate is raging among his advisers over whether to submit the still-missing Bush’s name for renomination. The president emerges from the suite to condemn leaks of the deliberations. Minutes later, under the tightest security, he goes to the convention floor and, brushing away tears, places Bush’s name in nomination. The floor erupts in a spontaneous two-hour demonstration.

At the Hyatt a computer check of room service records shows that the guest named Carlos has ordered three canisters of nitrous oxide and two years’ back issues of Cricket magazine. At midnight a specially formed SWAT team led by retired colonel Charlie Beckwith and Houston oil well fire fighter Red Adair cordons off the corridor outside Carlos’ room. A radio inside can be heard, tuned to KOAX, a Dallas “easy listening” station. “We’re goin’ in,” says Beckwith.

Thursday, August 23

Battering down the door, the SWAT team finds Vice President Bush tied to a chair, drugged, while Carlos installs braces on his teeth. “The kind you can’t take off,” the terrorist says. “The ugly kind that sort of bands across your mouth. I’m not saying your vice president has bad teeth. I’m saying my people are very, very angry.” Police rush Bush to Parkland Hospital and Carlos to the county jail. Aides let President Reagan sleep, explaining that he has a big day tomorrow, but they release a statement by him praising Bush, Beckwith, and Adair, calling them “old-fashioned national heroes.”

The question of the hour for the press: who is Carlos? The Morning News, in an editorial called “It Wasn’t Our Fault,” says, “Twisted individuals like Carlos can pop up anywhere, though we might note that he was not, in fact, a resident of the Dallas area.” Dan Rather broadcasts a special edition of CBS Morning News from Bolivia, where he discusses conditions that produce thousands of young men named Carlos and says Reagan’s Latin American policies “could have caused Carlos to embark on his doomed mission of protest.” He returns to the convention in a chartered Concorde in order to cover the acceptance speeches.

In the evening session of the convention Vice President Bush makes a dramatic, tight-lipped acceptance speech. He even manages a joke about his new braces, saying that as “the adolescent of the ticket,” he guesses he needs them. President Reagan’s acceptance speech is interrupted by applause 118 times and takes three hours to deliver. “Now, after four years of a Republican administration, America can walk tall again,” the president tells the cheering delegates, his eyes misting with tears. “And after our second term, ladies and gentlemen, I can assure you that they’ll be walking even taller.” During the two-hour demonstration that follows, Reagan is whisked to Love Field, where Air Force One is waiting.

Friday, August 24

At Norman and Nancy Brinker’s Ride to the Hounds breakfast at Willow Bend Polo and Hunt Club, Mayor Taylor calls on delegates and reporters to spend a long weekend in Dallas and says he’ll set up a commission to study locating the convention there permanently. “There’s a lot you haven’t seen,” he says. “There’s more than just stark poverty here. There’s also a lot of damn nice people.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Dallas