In late September, rumors erupted on local Del Rio Facebook pages that Haitian migrants on a plane leaving the airport for repatriation had begun to riot. Karen Gleason, a crime reporter for the 830 Times, a local news outlet that stepped up last November to fill a news void when the 136-year-old Del Rio News-Herald folded, went to the airport to investigate. There she found a host of law enforcement officers gathering around a single migrant who had fainted. There had been no riot. Gleason decided there wasn’t a story to pursue and went home.

Frank Lopez Jr. saw the same scene and decided, instead, to broadcast it. The former chair of the Val Verde County Republican Party and a retired Border Patrol agent, Lopez has nearly 22,000 followers from across the country on Facebook, where he livestreams under the moniker “US Border Patriot.” He paced along the airport fence, filming law enforcement and immigration authorities escorting reluctant migrants onto the plane. Even though there wasn’t a riot, Lopez stirred anxiety among his viewers. “They’re dragging ’em in; they don’t want to go; they resist; they fight; they push back . . . imagine when they come to your hometown and they don’t like the way things are,” Lopez said.

Within minutes, he had 38,000 viewers—more than the number of people who live in Del Rio. For nearly two hours, he harangued about immigration policies that repatriated some Haitian migrants while allowing others to pursue asylum in the country. There were no references or authorities cited for context, yet hundreds of appreciative comments for his version of truth telling came pouring in. One representative commenter wrote that Lopez “is out there and putting [his] life on the line to show us the truth.”

Del Rio, Lopez’s base, briefly became the center of national media attention in September as about 15,000 Haitian migrants gathered under the international bridge there. But after national journalists, who filled every hotel and room for rent for about three weeks, left town, there were few reporters to tell local stories. Val Verde County, of which Del Rio is the seat, had become one of more than twenty Texas news deserts, defined by the University of North Carolina as communities with limited access to credible and comprehensive news and information, after the News-Herald folded last year. That’s left room for Lopez to fill an information gap.

Lopez is not unique: in the absence of traditional journalism, many Facebook streamers have become go-to sources of news, particularly along the border. But their standards are typically far more lax than those of traditional media outlets, and their news often comes with an agenda. “The news desert is often filled with misinformation, disinformation, and propagandists,” said Jo Lukito, an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin. “From a journalistic standpoint it’s tragic to watch.”

Lopez, who has been broadcasting from the border since September 2020, tracks his rise to the folding of the News-Herald, as well as the rising anger among many Republicans over the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. His videos are rife with exaggerated stories about migrant crime and diatribes lashing out against politicians he says are responsible for unauthorized immigration. He thinks of himself as a citizen journalist, though he might be more accurately described as a social media influencer or propagandist. Months after the incident at the airport, I asked Lopez about his livestream. “I’m biased,” he said, “but then again, is there any unbiased reporting left out there?” As for his approach, Lopez is direct: “I’m trying to keep people informed,” he said, even if his editorial style is to “just throw out whatever I see in front of me.”

Traditional media outlets—which seek to verify information before broadcasting it—have also attempted to fill the Del Rio news desert. After the shuttering of the local newspaper, Joel Langton, an Air Force public-affairs veteran, decided to shift the focus of an events website he had created to news coverage, hiring on two reporters from Del Rio’s defunct newspaper. The 830 Times, so named because of Del Rio’s area code, is predominantly an online news site, but it prints a free weekly tabloid found at two hundred local establishments. One challenge it faces is the inordinate amount of time its reporters spend chasing false leads that spread like wildfire on social media, such as the rumor about the airport riot. Lopez, Langton said, “is trying to do a bigger picture of life along the border; that’s his brand. We’re focused on Del Rio and taking care of this community.” The Times occasionally hops on stories with national scope, covering immigration, but its bread and butter is local news: a freight train disaster, or a police investigation into the death of a person who fell from a highway overpass.

Though county officials trust traditional outlets such as the 830 Times more to disseminate information, they acknowledge Lopez’s larger reach. A typical story for the Times reaches a few thousand locals; Lopez, whose near-singular focus on immigration attracts national conservatives and who’s aided by “reporting” on stories other outlets deem not credible, regularly draws tens of thousands of viewers from around the country—sometimes a few hundred thousand. Lewis Owens, a Democrat who serves as the county judge of Del Rio’s Val Verde County, said his office shares important information with the 830 Times, local radio stations, and occasionally television news stations in San Antonio, 150 miles away. But he concedes that social media influencers such as Lopez are steering the political conversation. “You’ve always had them, but they’re more vocal now,” Owens said. While Owens disagrees with some of Lopez’s views, he calls him and others like him “necessary”: “I can tell you, for the most part, what they’re putting out there, it’s true; I don’t have a problem with it.”

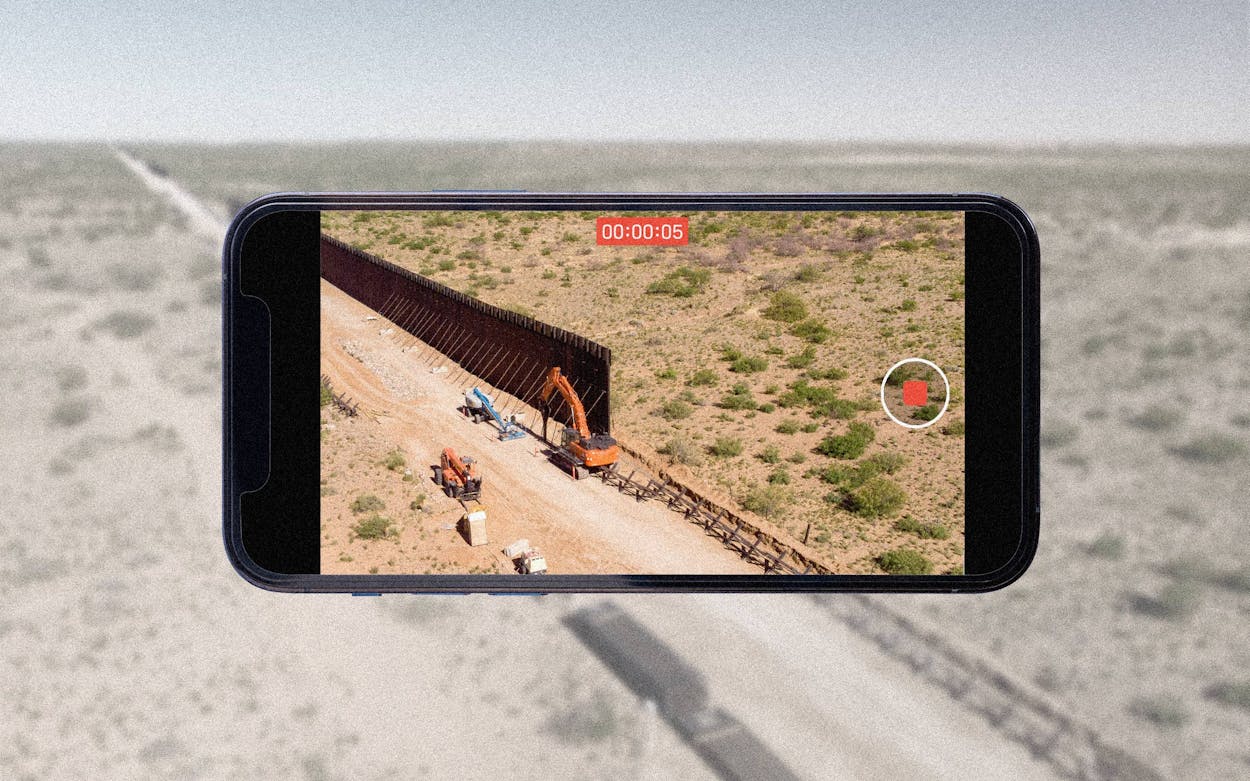

In recent months, Lopez has tried to stoke fears about an immigrant invasion and what he calls “the destruction of America.” More than 102,000 viewers tuned in to watch him document several holes cut into Governor Greg Abbott’s chain-link border wall in Val Verde, which he referred to as “Greg’s Gaps” while slamming the governor’s immigration crackdown as ineffective. In another video, filmed on Thanksgiving, that drew an audience of 219,000, he ranted from outside a humanitarian center that immigrants were being bused to the interior of the country to replace working-class Americans, saying that “the invasion does not take a holiday break.” In November, he accused humanitarian aid workers he was filming at a gas station of smuggling migrants for profit, before police were called to the scene to inform him that he could face criminal trespass charges. (It is unclear whether charges will be filed against him.) “Some police aren’t well versed in First Amendment rights, freedom of the press, and citizen journalists,” Lopez said of the encounter. “When you report here, what do they do? They call in law enforcement on law-abiding citizens.”

Lopez’s views, which place him to the right of even conservative Texas officials, have found favor among a geographically broad and vociferously anti-immigrant following. Audiences on social media tend to gather behind those they are already inclined to believe, allowing false stories to proliferate. “Once you don’t have to discern whether the information is true or false, then you end up believing,” said Jessica Collier, a postdoctoral research fellow studying the polarizing effects of misinformation at the Center for Media Engagement at UT-Austin.

Lopez’s newfound celebrity has launched him into right-wing state politics. He regularly receives invitations from law enforcement groups across Texas for speaking engagements. He isn’t sure he’ll carry on his “citizen reporting” much longer. For one thing, he expects that his commentary will eventually get him banished from Facebook and YouTube. (He’s not concerned about the weekly podcast he cohosts, called Tacobout It Live, on which he discusses issues of the border, faith, and politics.) For another, he’s seeking to use his newfound popularity to launch a bid for Congress in the Twenty-third District, which stretches from just outside El Paso to western San Antonio. After having resigned as chair of the Val Verde GOP in December, he’s running as an independent in a bid to unseat Republican incumbent Tony Gonzales, whom he says is a secret Democrat.

The 830 Times, meanwhile, has every intention of continuing its local reporting even if Lopez moves on. “This town deserves a news source, and the 830 Times strives to give them one,” Langton said. “In the long run, we’re going to have a stronger community for it.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Del Rio