The knock on his door came less than 24 hours after Christopher Flakus was raised from the dead. It had been more than six years since he’d overcome his longtime addiction to heroin and prescription opioids. He had finished his undergraduate degree, began pursuing a master of fine arts, and was teaching creative writing.

But the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic—followed by the end of a long-term romantic relationship and the February 2021 statewide freeze and blackout that burst pipes and destroyed his apartment—left the 35-year-old feeling “enveloped totally by despair.” The following May, almost without thinking, he’d shelled out $20 for a drug he hoped would bring relief.

The sidewalk dealer called it heroin. But after Flakus injected “a grain of rice worth” into the crook of his left arm, he took a few stumbling steps and then passed out. Luckily, his father came by not long after, saw him collapsed on the floor, and called 911. Houston emergency medical workers needed a full four doses of naloxone—a medication, commonly known by the brand name Narcan, that quickly reverses the effects of opioids—to bring him back to life. “It really was that Lazarus effect that they talk about,” he said. “It was just complete nothingness, then suddenly, boom, just back to consciousness.”

Subsequent tests, after he’d been transported to St. Joseph Medical Center, found that 90 percent of the drug mixture Flakus had injected was fentanyl, the potent synthetic opioid that has fueled much of the nation’s recent surge in deadly overdoses. According to the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics, the country experienced at least 101,552 drug-overdose deaths in the twelve months leading up to August 2022. The CDC attributed about 68 percent of those to synthetic opioids. Texas alone saw 4,964 fatal overdoses during that period, 41 percent of those involving synthetic opioids. Many can be attributed to fentanyl, believed to be the leading cause of overdose deaths—and all deaths—among Americans ages 18 to 45.

Fentanyl has become increasingly prevalent in recent years because of its relatively low production costs. As a result, in its powdered form, it’s been surreptitiously mixed in with a variety of other drugs. Users ingest substances that are more potent than they realize. Fentanyl is roughly fifty times more potent than heroin and about one hundred times more than morphine. It’s intended for use only in highly controlled medical settings.

The man who knocked on Flakus’s door the day after his overdose was a peer coach with the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System (HEROES), an experimental effort launched in 2018 to stem the tide of overdoses. Typically, the approach to combating opioid addictions and deaths has been a purely reactive form of triage conducted by first responders: an overdose patient is treated by EMS, possibly taken to a hospital (EMS protocols vary), and then released without much, if any, follow-up. Repeated overdoses are common among those with an opioid-use disorder.

Thanks to modern emergency medicine, bringing someone back from the dead is often the easy part. Keeping them alive and healthy for the long haul represents the true challenge. HEROES, along with similar programs in Austin, El Paso, and San Antonio—as well as dozens of efforts in other states—aims to reduce deaths by dispatching what could be called “second responders,” to provide ongoing support to those who have overdosed. “He was like, ‘We want to help you,’ ” Flakus said of the HEROES counselor who first visited him. “I was like, ‘Yes, yes, yes to all of that.’ ”

HEROES launched as fentanyl deaths and overdoses began making headlines nationwide. The Texas Department of State Health Services reported that deaths attributed to fentanyl rose from about 210 in 2018 to 1,612 in 2021. In Harris County, overdose deaths involving fentanyl increased from 104 in 2019 to 459 in 2021, topping a list of spikes in the state’s counties, including, in descending order, Dallas, Tarrant, Bexar, and Travis.

The second-responder approach begins within 48 hours after someone has had a documented overdose, a period during which a patient with an opioid-use disorder is particularly susceptible to a second overdose—and also, in many cases, more willing to make an attempt at recovery. The goal is to direct habitual opioid users toward addiction treatment that’s often a combination of drug counseling, medication, and talk therapy. Working in partnership with local EMS, HEROES deploys a paramedic and a peer coach—a trained specialist with personal experience in addiction and recovery—straight to wherever the patients are living.

HEROES has grown from four employees in 2018 to more than twenty full-time staffers, including six peer coaches, a physician assistant, two counselors, and several researchers. The program is led by James Langabeer, the director of UTHealth Houston’s Center for Health Systems Analytics and a professor of emergency medicine. He estimates that since its founding, the program has helped between 15 and 20 percent of those who overdose in Houston to seek addiction treatment.

Of those participants, between 80 and 85 percent remain in recovery for at least ninety days. That’s a remarkable success rate. Barring a full-time, $100,000 course of treatment in a facility that only 1 percent of the population can afford, Langabeer said, “the industry norm is that ninety percent of people with an addiction will lapse within the first month.”

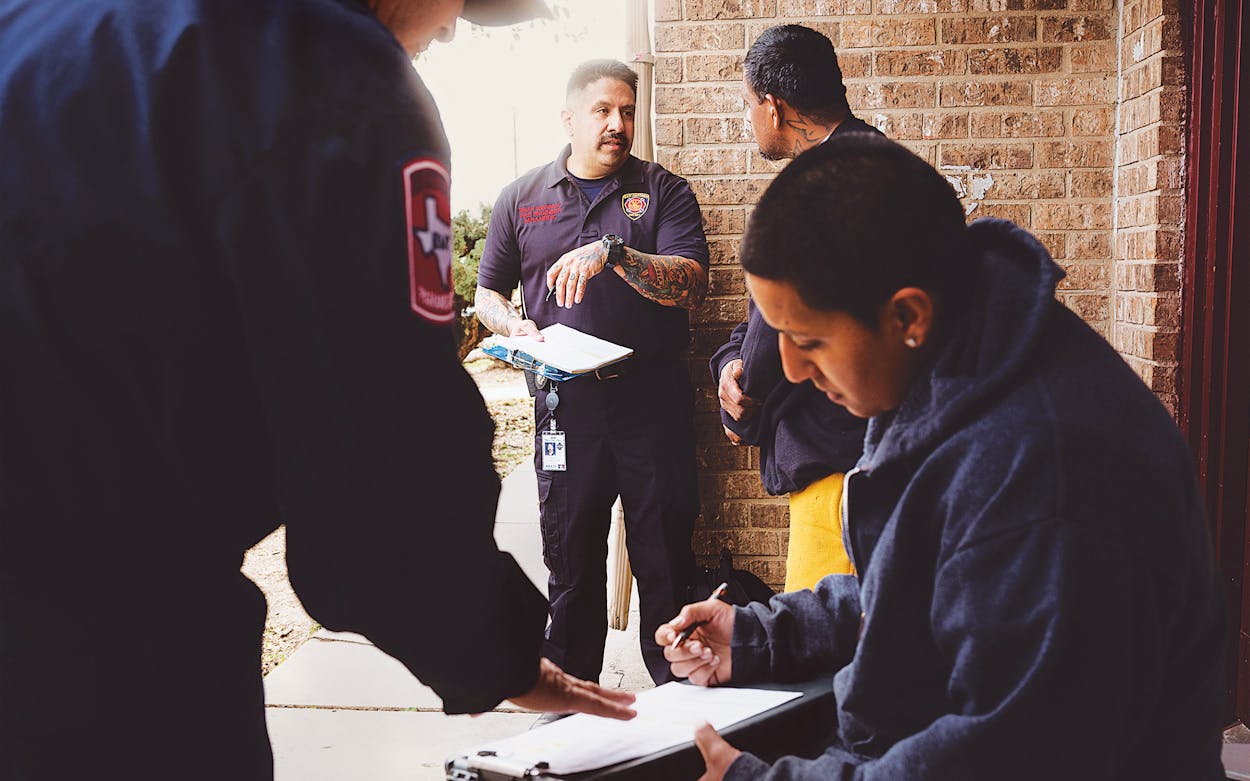

Riding along one Sunday with second responders in San Antonio showed me the value of quickly connecting with those who have overdosed. The three-member team came from a special unit of the city’s fire department, created in 2018 and dubbed TTOR, for Texas Targeted Opioid Response. Paramedics John Briones and Brian Guerrero drove with Leroy Garcia, a professional substance-abuse specialist, for eight home visits to recent overdose survivors throughout the San Antonio area.

In a picturesque West Side neighborhood, they moseyed out of a Ford Explorer and onto the tidy front porch of a woman in her early twenties who’d recently been a few shallow breaths short of death before she was saved by EMS with the help of naloxone. Now, on this sunny afternoon, she brightly chirped in conversation as Briones checked her blood pressure.

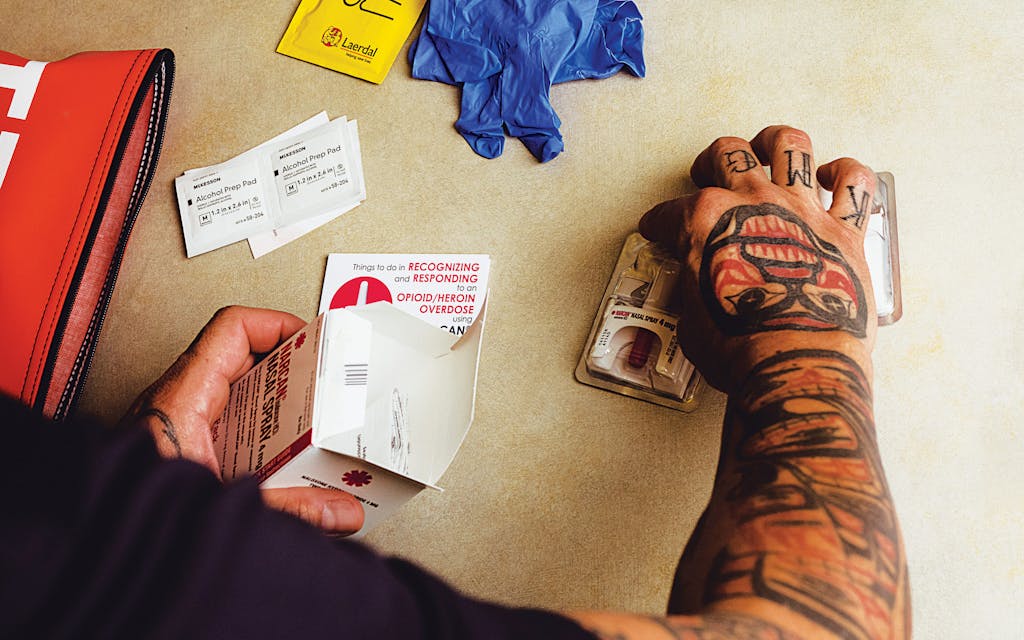

In addition to taking her vitals, the TTOR team gave her a bag of overdose-prevention essentials, including Narcan nasal spray and wound-care supplies for intravenous drug use. Next came the more difficult task of providing guidance for long-term addiction recovery. That’s where Garcia, who’s with the San Antonio Council on Alcohol and Drug Awareness, comes in. Seven years sober after more than one overdose of his own, Garcia often can relate to patients in ways that other second responders can’t. “He’s living it,” Briones said. “It’s not from a book.”

While HEROES, in Houston, offers treatment directly, San Antonio’s TTOR can only make referrals elsewhere. If a patient is willing, as this young woman was, Garcia helps create a plan for the next few days of sobriety. He can recommend substance-abuse counselors and assist in registration for free or low-cost outpatient rehab, as well as supervised dosing of drugs such as Suboxone or methadone, which are the primary long-term medications used to treat opioid dependency. He’s got taxi vouchers as well, for those who might need rides to treatment.

For patients experiencing opioid withdrawal symptoms, the TTOR team can even provide Suboxone, which includes the medication buprenorphine, an uncommon course of action given that most agencies in Texas and elsewhere don’t permit paramedics to administer it.

Not every interaction that Sunday went smoothly. The TTOR team caught up with a fidgety fortysomething man with a shaved head and faded tattoos as he shuffled around the dirt yard of a shotgun shanty teetering upon too few cinder blocks. Garcia typically asks a patient who’s acting like this whether he’s using drugs to get high or just not to be sick. If it’s the latter, Garcia said, you’ve got a better chance of reaching him because “the fun is gone.”

But just five minutes later, after giving the man some Narcan to have on hand in case of another overdose, the team left. He seemed to them unlikely to attempt recovery anytime soon. Nor did he qualify for a withdrawal-suppressing dose of buprenorphine, because he’d used illicit drugs that very morning. “The fact is that some people are still going to use,” Guerrero told me. “I feel bad when we can’t help.” And, of course, some people don’t want help.

The team always leave a card, even if no one answers their knock. If they get a call back, it can just as likely be an unambiguous warning to stay away. At a run-down collection of ground-level apartments, the brother of a potential patient shouted, “Y’all don’t have to live here,” taking off his shirt and coiling up as if preparing for a fight. “I’m stuck in this bitch twenty-four seven!” The TTOR team made a smooth exit, noting en route to the Explorer that the brother had also been recently revived by EMS following an overdose. “You can’t expect people to change overnight,” Briones said.

I asked Briones and Guerrero how many of their visits result in the patient taking steps toward recovery. Briones estimated that only during 20 percent of their calls are they able to locate the person who had overdosed, and only about 20 percent of those will agree to seek treatment. That would mean about a 4 percent success rate. Those numbers can make their objective feel, at times, hopelessly Sisyphean. Yet that isn’t the attitude they bring to the work. “It’s all baby steps,” Guerrero said.

In Texas and nationwide, politicians and others addressing illegal drug addiction have rarely been satisfied with baby steps. State leaders have made a show of massive fentanyl drug busts and warned against the dangers of nonexistent opioid-tainted candy. Meanwhile, they cast aspersions on supportive treatment and supervised drug use—parts of an approach known as harm reduction, which primarily seeks to reduce the negative impacts of the disease of drug addiction. “When the program first started, nobody was receptive to it,” Guerrero told me. “Not even our union.”

But attitudes are changing. “More and more, somebody knows somebody” who’s overdosed or been addicted, Guerrero said, echoing something that Langabeer, in Houston, had mentioned. “We have a toll-free, twenty-four-hour phone number where anybody can call and say, ‘I’d like to talk to someone about options,’ ” Langabeer said. HEROES keep tracks of the after-

hours calls it receives—more than three hundred per year. “That number is constantly increasing month over month. And I think that’s a sign that people are starting to see [long-term drug use] as a problem and recognizing it in themselves.” In addition to serving 1,200 program participants since its inception, HEROES has provided advice and counseling to 20,000 opioid users and their family members.

Some top Texas officials also seem to be changing their attitudes on harm-reduction methods. Visiting the University of Houston in December to highlight its researchers’ development of a vaccine that could negate the effects of fentanyl, Governor Greg Abbott announced his support for decriminalizing fentanyl test strips, which can help prevent overdoses by detecting the presence of the drug mixed with other substances.

That could be part of a larger sea change, which includes the increased accessibility of free Narcan, even though some opponents believe it increases the use of illegal drugs. (A spokesperson for Senator Ted Cruz, for instance, told the Texas Tribune last year that giving people tools that let them continue using drugs doesn’t help.) Harm-reduction programs also could be spreading to new locations elsewhere in the state. Langabeer said HEROES is working on developing programs for Bastrop County and Beaumont.

This second-responder approach doesn’t often yield immediate results. It’s not nearly as simple as zapping someone back to life with a few milligrams of Narcan.

“That’s what we’re gonna try to do from the ground up in small communities, the rural communities across Texas,” he said. “My harm-reduction analogy is always thinking about things from the heart perspective. When we started putting out those defibrillators in places, people started realizing, ‘Oh wait, heart attacks do kill, and I can save a life.’ And that’s kind of what we want with this.”

San Antonio deputy fire chief Andrew Estrada notes that TTOR and similar programs differ from how most institutions have approached the opioid epidemic. “When you start looking at any of the programs across the country, it’s like, wow, you’re only helping a low number,” he said. “That’s a doozy, because when you start looking at it, people want to see returns for investment.”

Yet it costs about $1,000 a day to staff TTOR. In the twelve months leading up to last September, the program reached 3,266 patients and referred 315 of them into treatment programs. That’s a success rate of less than 10 percent. And neither TTOR nor HEROES can yet point to evidence of having contributed to a decline in the number of overdoses in their cities—though they certainly hope that’s the outcome.

This second-responder approach doesn’t often yield immediate results. It’s not nearly as simple as zapping someone back to life with a few milligrams of Narcan. It’s a kind of health care that requires resources well beyond the medical—raising public awareness of the crisis, destigmatizing opioid-use disorders, and boosting cooperation among numerous entities, public and private.

Five minutes into my conversation with Flakus, it’s clear how much his quality of life has improved since that first visit from HEROES. He attends two peer-support groups every week and has a drug counselor who can offer advice regarding his prescription Suboxone treatment. “The beauty of the HEROES program is that you can come and go,” he said. “No one’s gonna monitor you. No one’s gonna chase you down and force you to attend group [therapy],” he said. “I think one thing we have learned about recovery is that the best approach is multiplicity. You know, not one-size-fits-all.”

Since he joined the program, Flakus has finished his MFA at the University of Houston and moved out of state. He continued to meet remotely with a peer coach. HEROES offers telehealth options, not to mention a recovery-tracking mobile app, and it plans to incorporate Fitbit innovations. “I felt really . . . surprised that a program like this even existed, for free,” Flakus said. And then he caught himself, adding that “the price of admission is rather high.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Overcoming Opioids.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Health

- San Antonio

- Houston