In an auditorium in Allen on Sunday evening, Greg Abbott closed his eyes for a moment of silence. The governor had traveled to the North Texas city to attend a vigil for the eight victims shot to death by a Dallas man wielding a semiautomatic assault rifle in a mall on Saturday afternoon. Shortly after the vigil commenced, one of Abbott’s Twitter accounts sent out a photo of the governor bowing his head. “As this community heals, Texas will be with you every step of the way,” the tweet read.

Just twelve hours later, Abbott spoke at a microphone set up in front of two massive C-130 military cargo planes on the tarmac at Austin-Bergstrom airport. The governor tweeted out a photo of the sunrise-lit podium. “Up bright and early to provide a border security update ahead of the end of Title 42,” he wrote, referring to the public health statute that has been used since March 2020 to essentially block migrants from applying for asylum in the U.S. In the press conference, Abbott unveiled his latest military mobilization: a newly formed Texas Tactical Border Force, a group of “elite soldiers” from the state National Guard tasked to “repel illegal crossings”—a federal mission that legal experts say Texas does not have the constitutional authority to undertake. As armed troops marched behind him, Abbott ended the news conference, and a cameraman set up lighting for an on-air interview with Fox & Friends.

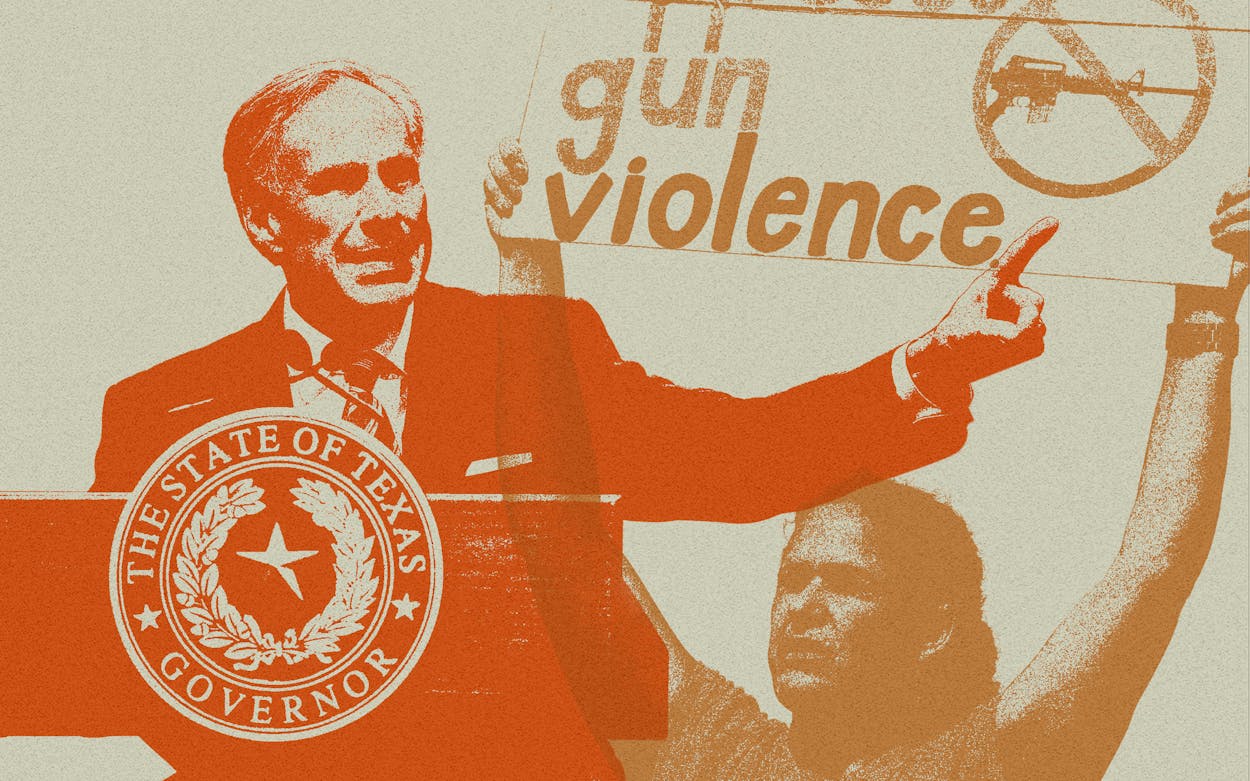

With 1,254 miles of the Rio Grande, Texas maintains the longest international border of any state, and it’s proven politically useful to Abbott in times of domestic crisis. The border, in Abbott’s depictions, is beset by enemies, criminals, invaders—dangerous Latin Americans—that he can point to whenever he wants Texans to look away from the bodies of children in our malls, classrooms, and churches.

Obviously, Abbott can—and must—care about more than one issue at the same time. In recent years, the Texas border indeed has been in crisis: the number of asylum seekers surrendering to authorities has strained both Border Patrol and local infrastructure, from shelters to bus stations. But as he avoids questions on gun reform or punts the issue to other state leaders, it’s hard to see Abbott’s obsession with the southern frontier as purely logistical; often, it’s simply a backdrop when he needs a PR boost.

The governor was in top form during his Fox interview: forceful, direct, and clear. Talking about the border less than 48 hours after the Allen shooting, Abbott had pulled back the narrative to his comfort zone. He talked fluently about cartels, fentanyl, and an “invasion” of desperate migrants. Abbott can explain what’s happening on the border much more readily than he can explain why citizens of his state are killing children with powerful weapons intended for combat.

Abbott had recent training for this moment. Just a week before the Allen shooting, a man in Cleveland, about fifty miles northeast of Houston, went on a drunken massacre, murdering five of his neighbors including a nine-year-old. Talking to reporters about the shooting, Abbott chose not to address the issue at hand: why gun violence has become so common in Texas. Instead, he focused on the immigration status of both the shooters and the victims. Taking to Twitter again, he described the victims as “5 illegal immigrants.”

In fact, at least one of the victims was a permanent legal resident. But that didn’t prevent Abbott from making noncitizens the scapegoat for his failures of leadership. Border security and immigration reliably poll as the number one issue of concern for Texas Republicans, while addressing gun violence is a priority for Democrats. Suddenly, Abbott had turned Cleveland from a story about out-of-control mass shootings into another narrative about the dangers posed by immigrants.

In late April, Abbott even implied that gun violence—a decidedly American problem—is the fault of the cartels, incorrectly claiming that cartels are bringing “dangerous weapons” across the border into the United States. In reality, the vast majority of guns crossing the border are smuggled from the U.S. into Mexico, according to Mexican authorities.

The Texas governor is hardly the first American politician to recognize how politically useful undocumented immigrants can be. In the 1880s, as working-class Californians struggled to find work in squalid and polluted cities, California’s robber barons engineered an ingenious strategy to shift blame to Asian immigrants. The United States passed its first immigration control law in 1882, the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act. Ever since, scapegoating immigrants for the sins of the United States has been an effective political maneuver by elites in government and business.

A similar strategy was in play on the Austin airport tarmac. When a reporter asked Abbott, over the din of the C-130s’ engines, about the shooting, the governor began to reply that he was concerned about the “devastation” the families had experienced. For audiences watching live at home, the rest of his answer was cut off—the official live feed ended midsentence. The press conference was adjourned and, moments later, Abbott began his Fox & Friends interview about the border.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott