There are few opportunities like a State of the State speech for a governor to shine. In his remarks to open the legislative session last January, Greg Abbott proved why he’s often seen as the best politician in the state’s recent history—and the worst. Abbott spoke with an aura of self-congratulation, thanking family and the Legislature’s Republican leadership, saying, “Today I am proud to report the State of Texas is exceptional.” He highlighted some of the victories from his first session, in 2015—securing money for new highway projects and a robust border security package. He laid out his agenda, including more property tax cuts, more border security, and more education options. He called for a better child protective services system and legislation to restrict abortion. It was the type of speech that one might expect from the governor of an exceptional state.

But then Abbott held out an open left hand, in an almost accusatory manner, and pointed toward the senators and representatives gathered in the House chamber. He declared himself “perplexed” that they were reversing course and refusing to double the funding for his high-quality pre-kindergarten education plan, which had passed two years earlier. “Let’s do this right,” Abbott grumbled, “or don’t do it at all.”

He should not have been so perplexed; the legislative indifference he faced was his own doing. Months later, as the session neared an end, it appeared he would not get his new funds.

That’s basically the Abbott governorship in a nutshell: some clear ideas, some concrete accomplishments, and a baffling ability to alienate the very people he needs to make his ambitions come to life. Three years into his administration, it’s tough to form a sense of the sum total of that tenure. He’s looked more like a governor worried about reelection than one seeking to establish a long-term legacy.

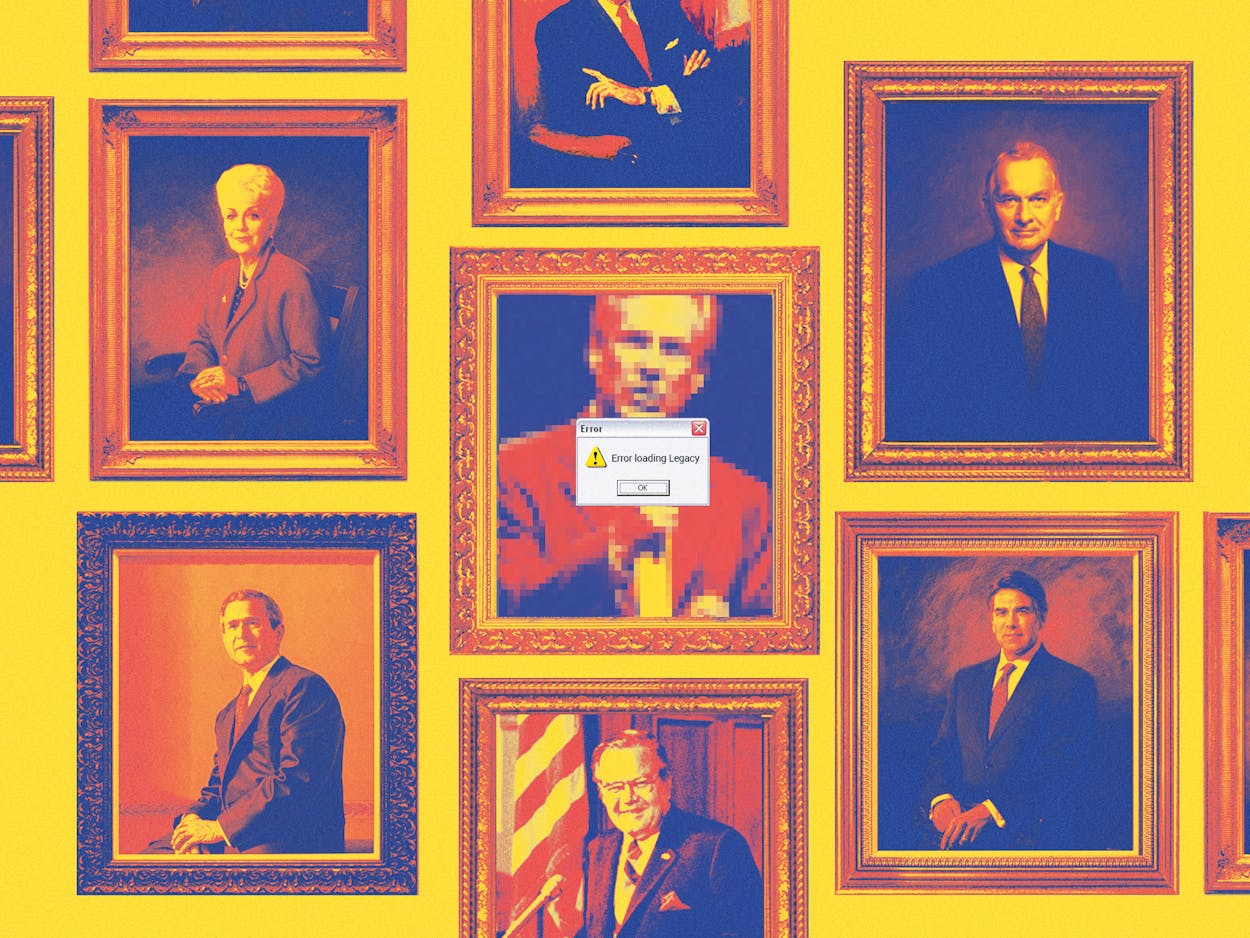

Abbott’s ballot-box drubbing of Wendy Davis in 2014 ensured that his portrait will hang in the Capitol rotunda, but legacies are built on more than oil paintings. Through his first three years in office, Abbott reigned with platitudes, sowed narrow visions for the state’s future, and in the end, seemed to succeed in spite of himself. As he enters his campaign for a second term, the question remains: What kind of governor does Greg Abbott want to be, and how does he want history to remember him?

His term certainly started strong. He persuaded legislators in 2015 to fund his signature $800 million border security initiative. He got $2.5 billion earmarked for new highway construction. He appeared at a shooting range and signed his open carry legislation into law.

But cracks also started to form. Social conservatives aligned with Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick called Abbott’s pre-K proposal “godless” and a form of socialism. In order to get votes, Abbott promised some House Republicans that he would publicly support their reelection if they supported his pre-K bill. Some did, despite heavy tea party opposition, but then Abbott failed to follow through during their subsequent campaigns. For legislators, this reneging on this promise “began to seep into the water table, this sort of poisonous attitude,” said longtime lobbyist Bill Miller. “There wasn’t a sense of ‘Let’s go help Greg Abbott.’ ”

During this session, lawmakers threatened to cut more than just the pre-K funding. They also considered seriously reducing the money in his enterprise fund, used to attract out-of-state businesses, and altogether eliminating a film incentive program managed by his office. Not long after his State of the State address, Abbott surprised Senate finance chair Jane Nelson in her office and berated her for leaving his pre-K program out of her Senate budget. Then Abbott seemed to vanish, only to reappear months later at the eleventh hour of the House and Senate budget negotiations to intimate that he would veto the entire state budget if cuts made to his office were not restored. (Lawmakers gave the governor’s office an additional $110 million.)

Abbott also angered members of Texas’s congressional delegation as they sought federal recovery money following Hurricane Harvey. After the House unveiled a relief bill that didn’t include $18.7 billion requested by the governor’s office, Abbott complained to the Houston Chronicle that the Texas Republicans in Washington needed to get a “stiff spine” or they would get “rolled” on the Harvey aid package. But Abbott didn’t seem to understand that the money he wanted was still on the table, and several members of the state’s delegation said privately that Abbott’s comments complicated the already tense negotiations over relief funds. House speaker Paul Ryan had to call Abbott to explain that his anger was misplaced.

However, while Abbott has shown a knack for upsetting fellow politicians, this has not hurt him with voters, who tend to care about results. Federal hurricane funds continue to flow to Texas. The Legislature approved an overhaul of the state’s child protective services. A controversial sanctuary cities law, designed to punish local officials who do not fully cooperate with federal immigration authorities, passed as well. Legislators gave him a resolution calling for a convention of states to offer constitutional amendments to restrain the power and spending of the federal government, one of Abbott’s pet projects. Even though legislators chose not to provide new state dollars for Abbott’s high-quality pre-K plan, they mandated that school districts dedicate some of their state funding to pre-K programs.

And after Hurricane Harvey ravaged the Gulf Coast, Abbott showed up at one media briefing after another, wearing a blue windbreaker or a tan fishing shirt with the state seal over the left pocket and “Greg Abbott, Governor” embroidered over the right. Even when there was criticism from Houston mayor Sylvester Turner and Harris County judge Ed Emmett over Abbott’s early suggestion that Houstonians should evacuate the city, what the public largely saw on television was Abbott as the Texas commander in chief of storm rescue and recovery. Republican consultant Matt Mackowiak said Abbott rose above his partisan image to “do the job you expect the governor to do in a crisis situation,” which added to his strong political standing.

Abbott’s standing in the polls is, in fact, formidable, as is his fund-raising prowess: he has gathered $44 million over the past two years, and he opens his campaign with the largest war chest in state history. That money has helped shield him from any major would-be opponents. He’ll face only two minor candidates in the Republican primary, and on the Democratic side, first-tier candidates have stayed away. Abbott’s name recognition with voters is high, and his job approval numbers, among voters from all parties, are in the mid to high 40s. A poll that circulated among the state’s leadership at the end of last year found that Abbott would start his campaign with an advantage of more than 10 percent against any unnamed Democrat.

“The sense that there’s a lot of dissatisfaction with the governor among insiders is, in fact, an insider’s perception,” University of Texas political scientist Jim Henson says. And yet the big question remains. What does Abbott want as his legacy? Ann Richards had her New Texas. Mark White and George W. Bush were education governors. Rick Perry built roads, limited lawsuits, overhauled property taxes, and expanded business development.

Abbott, for the moment, seems content to run a more-of-the-same campaign as the conservative chief executive of an exceptional state. “I have news for the liberals: Texas values are not up for grabs,” Abbott said on the day he formally announced for reelection. “I’m committed to preserving your Texas liberty.” Not much in that promise will be remembered twenty years hence.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott