Last August, in the immediate wake of Hurricane Harvey, Texas Monthly produced an oral history of the devastation the storm wreaked upon our coastal areas. We spoke to 28 people about their experiences of flooding and destructive winds, as well as the generosity of folks who rushed in to help. A year later, we caught up with nine of them to see how they’ve fared since.

Gretchen Smith

40, a stay-at-home mom in Katy who tried to hunker down in her house until rising floodwaters forced her to flee

After the storm, we lived with my mother-in-law in Katy for four months, and then we got home Christmas Eve. The hardest part, for us, has been emotional. We had flood insurance. We had a free place to stay very close. But there’s the stress that your normal routine is just gone. And you relive it when it rains. Anybody you talk to in the Gulf region will tell you: anytime it rains, your heart kind of stops a little bit.

But a lot [that’s] positive has come from the storm. There is a much tighter sense of community now. You had crews going [around] mucking houses, bringing food, dropping off water. One church brought us food for two months and gift cards.

We had a thank-you party once we moved back in. We had sixty-something people here—all the people that helped. You look around and realize: that’s what life’s about, right? To be surrounded by people who love and help you when you need it.

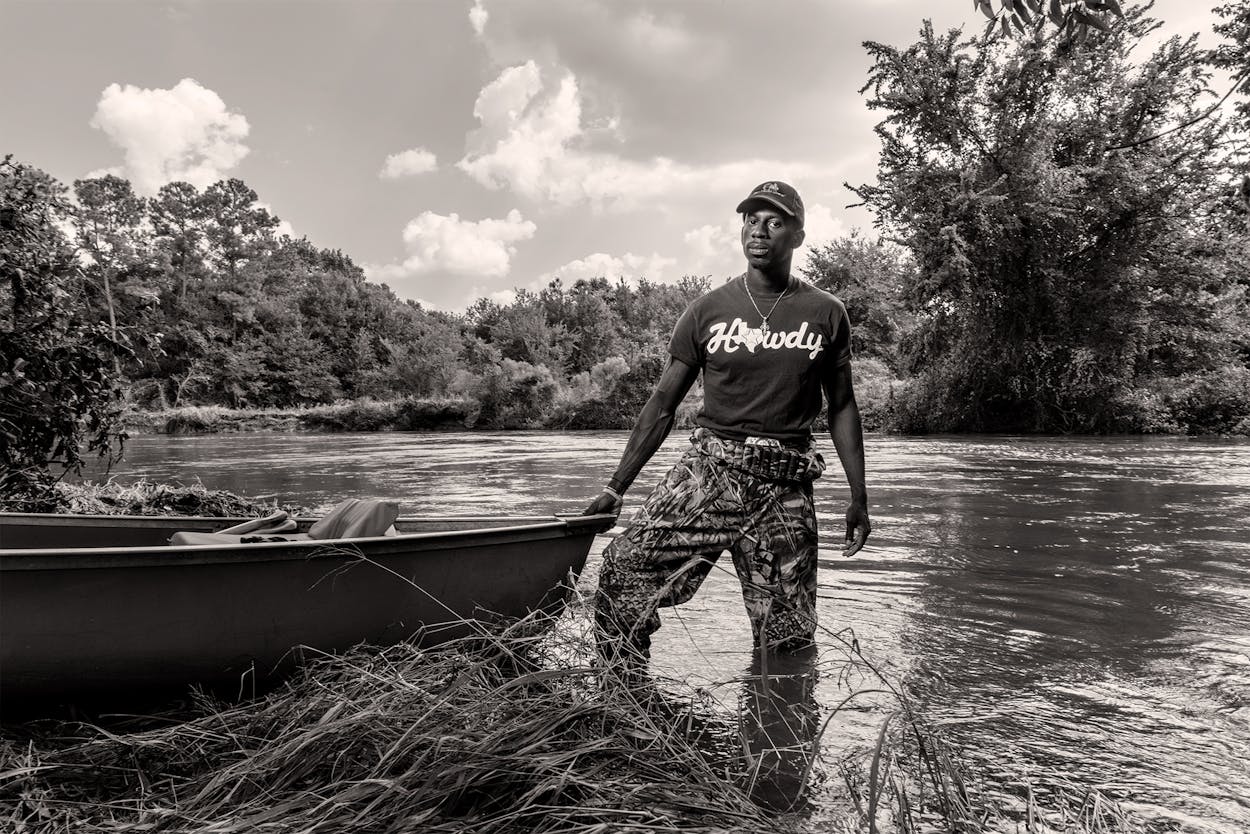

Tyree Finley

27, an outside sales manager at wayfair.com from College Station who performed rescue work in Cypress

My friends and I delivered supplies for the first few weeks after Harvey—water, tools, cots, food. One thing that I took from that whole experience: there are so many amazing people in this world. When we were out rescuing and delivering supplies, we met people from Alabama, Florida, New York, even Canada.

A lot of people have gone back to their normal lives, and they just hope that it doesn’t happen again. This is what I would suggest: get some flood insurance, a generator, propane heaters, propane stove tops, matches, a knife, waders.

I got all these things after the storm. I even bought a camper. If something happens and I need to leave my home, I can throw things in my camper and I’ll have somewhere to stay. And I can fit six or seven people in there with me.

Mary DeGarmo

63, a retiree in Vidor who was forced by rising floodwaters to escape her home by boat

You just can’t imagine what it was like to come back home. I had seen the pictures and videos on Facebook, but until you’re there and you can see it and feel it and smell it—it just smelled so hot and steamy, like in a bayou—you can’t really imagine.

When my son drove us home in his Jeep, about three weeks after we evacuated, I was thinking, “Oh my God, do I have a car?” You know, and “How bad is the house?” And I was thinking of the animals. When the boat of rescuers from Oklahoma pulled up and said, “We’ll take all your animals,” I took our five dogs. But I had seven cats who stayed at the house. I was so surprised when we got back and all of the cats were here and they were okay—when we left, you could see fish in our yard in the water, so I guess there was enough for the cats.

A friend of mine found a set of bones on a concrete bench in her mobile home park, and she said, “I think it might be a coyote or something.” I told my daughter, “That’s probably a dog that almost drowned during the flood and made it up there but then died anyway.”

Sandy Skelton

70, a retiree in Beaumont who also escaped her flooded home by boat

Everything in our house had to be towed or hauled out, which friends and family members helped us do. And then everything had to be replaced: the walls, insulation, the Sheetrock. We had to stay with other people for eight weeks as they treated the mold. We had flood insurance, and they covered the contents of our house, but we’re still working on the building part.

The rebuilding process has been rough. It was hard to get a contractor because they’re so busy. When we got a contractor in October, we were told they’d be done by Christmas, and the house still isn’t finished. The workers will come out for two or three days, and then we don’t see them for three weeks to a month.

We’ve had a lot of trouble with FEMA. Of course they’re going to help the people that don’t have insurance first, but they’re not even helping them that much. I went to where they had their people set up to help, and they gave me a phone number for somebody, and you call that person, and they give you a phone number for somebody else, and you call that person, and they give you another phone number for somebody else. They weren’t helping at all.

It makes me very anxious when it rains, even though I do have trust in God it won’t happen again.

James Canter

46, a chef who turned his Victoria restaurant, Guerrilla Gourmet, into a pay-what-you-can cafe and mobile food service during the storm, serving thousands of hungry hurricane victims

In the weeks afterward, it got big, man—we were feeding three to four thousand people a day. We had the restaurant going, and we had the food truck going, two mobile kitchens, and a pop-up kitchen out in that parking lot. It was nuts, man.

But business was already rough that year [because of the drop in fracking jobs in the area], and it didn’t get back to normal. No one had the disposable income like they did before. My landlord gave me the place rent-free, which was very kind. But I had to pull up stakes before I went completely bankrupt. We were just like, “Let’s get rid of the restaurant, let’s work out of the truck—go back to the basics.” I had to lay off five or six people. I’m the last man standing.

I got asked to do one of the TV shows on the Food Network, which I did. So there’s a lot of great opportunities on the horizon. My family, we’ve moved to San Antonio. The truck is in San Antonio now, and it’s still scootin’ along, man. It’s still scootin’ along.

Claude Brown

60, a former deputy constable and former mayor of Port Aransas who rode out the storm in his house, which was inundated by water

It’s a slow recovery. I’ve got my house situated enough to live in, but as far as the island goes, a lot of the condos are still wrecked. The chamber of commerce is telling everyone how wonderful life is in paradise, and they are blowing smoke up people’s butts.

A good friend of mine owns Moby Dick’s restaurant, a big place here in town. He’s having a hard time keeping it open because there is hardly any help. Nobody can live here, even though he pays good wages. I put my place on the market. I just want to move along.

Port Aransas will come back, but the people that are running this town right now, I am not optimistic about. Most of the people on the council moved here because they didn’t like it where they were, and they want to change it to be like what it was where they came from. If you want to quote me on that, that’s fine. I don’t care. I told them the same thing.

Joe McComb

Corpus Christi mayor

I knew we had to do something to help [Port Aransas], so we established the Mayor’s Hurricane Harvey Fund. There is no tax money associated with the fund. We worked with the Coastal Bend Community Foundation to get money directly to the organizations who are helping people the most. We raised $991,517.20, and we have distributed $865,000 as of August 1.

We had people from 36 states across the country contribute to the fund. Port Aransas is making great strides, but it is nowhere near fully recovered. It will take years. The biggest problem right now is the housing issue and all the bureaucracy people are having to go through to get insurance coverage. It seems the insurance companies and FEMA are bending over backward to make sure someone doesn’t scam the system, and these background checks take a lot of time, but we’ve got to figure out a better, faster way to meet people’s needs.

There is much more work to be done in the recovery, and I am inspired by all the people who are still helping. Right now, there is a group of 150 college kids staying in the First Baptist Church of Corpus’s gymnasium for the week, who are going over to Rockport every day to repair roofs. We all just have to keep helping each other.

Susan Detweiler

60, a volunteer chaplain with the Beaumont police department who was rescued by boat from her home

The days after the storm all kind of run together, from the time I woke up at 4:30 a.m. and realized I had six inches of water in my house until about a month and a half later. I had lunch with my daughter one day, and she said, “Mom, I think I’m having PTSD.” I said, “I know for a fact you’re having PTSD, because I am too, and so is just about everybody else in this area.”

It probably took me a couple of months to really try to get past that, because it was, like, everything that’s normal, everything you’re used to is gone. The rocking chair that my great-grandfather had made, my picture albums from my kids growing up, my Bible—they were gone. Those kinds of things are really tough to replace. It’s hard.

I’m the volunteer manager and the donation manager at the Southeast Texas Food Bank, so they were in a hurry for me to get back, because we had all these donations pouring in. I rented a place really quickly, bought a lawn chair and a queen-size air mattress, and started working ten- or twelve-hour days, just inputting checks and money into the system. Once I got a handle on that and got a few things at home, it felt more like things could get back [to normal].

It also really helped that I had my animals with me, in particular my Boston terrier, Crayfish. Because of the dogs, I’ve got somebody to hold on to, something warm that is glad to see me when I get home. I’m a widow and I live by myself—people say you end up as a crazy old cat lady or dog lady, and I can see very easily how people become that. If you don’t have a lot of other people in your life, that’s where you give and receive love.

Bobby Sherwood

60, Nueces County constable, Port Aransas, who rode out the storm with Claude Brown

After the storm had gone through, the town was just a total disaster. We saw cars in the street, power poles down, travel trailers . . . the streets were just littered with anything that didn’t weigh very much. As law enforcement, our job was to protect the town from looters, but people looked to us not only for physical support but for mental—for somebody to talk to. We didn’t have any cell service over here for days, so they couldn’t call you, but they would flag my people down and thank them—shake their hands and tell them they appreciated it.

The day they came to demo my house, in December, was pretty trying. I mean, you look out there and you see everything you own and everything you’ve worked for over the last forty years go to the curb and [get] hauled off in trucks. I raised both my kids in that house, and all my grandkids would come spend the summers there. It was devastating to my wife also, because we lost the kids’ pictures and things that just can’t be replaced. That was tough. We weren’t the only ones—there were [five] of us in a line, from my house down to the next four houses, that were all torn down.

This is a real resilient community, and we couldn’t do it without most everybody helping each other. But it’s going to take the town a long time to come back. We’ve made some progress, but we won’t be back to normal for quite a while. I’ve been here since the mid-seventies, and I go around and see where all them old houses are being torn down—it’s pretty devastating to think that I knew people that lived in them for damn near all my life and then now they ain’t got no home. We’ve probably lost 30 percent of the full-time residents that we had before, maybe more. A lot of people have sold their homes and said, “I’m not coming back.”

- More About:

- Hurricane Harvey

- Houston