The stories that Rodney Young has heard again and again from former students—physicians working in small towns surrounding Amarillo—have been bleak. They’ve told Young, a family doctor who teaches at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, in Amarillo, of how they’ve had to transfer critical patients to hospitals that are hours or even states away because of ICU bed shortages when COVID-19 cases surge.

One doctor spent hours trying to find a hospital with enough capacity to treat a man suffering from acute limb ischemia, an emergency in which a limb is not getting enough blood. The doctor finally found a hospital in Phoenix—seven hundred miles away—that could take the man, and he was airlifted there by plane. Young’s former student didn’t hear what happened after that, but a bad outcome was made “much more likely,” Young says, because so much precious treatment time had been wasted. “There’s a million and one anecdotes like that,” Young says. “Somebody gets displaced from care that should have been available locally.”

In pre-pandemic times, patients with trauma or other critical conditions would simply be transferred to a nearby hospital—maybe one that’s just up the road or one in Amarillo or Lubbock. But, of course, these have not been normal times. At various points during the coronavirus pandemic, hospitals of every size across the state have seen demand for ICU beds surge to or beyond their limits. That’s been an issue for hospitals nationwide, but it has been particularly acute in Texas, where a decade-long consolidation of the health-care industry has left many of the state’s small communities without hospitals of their own and left urban hospital systems—even though they have built billions of dollars’ worth of new facilities in recent years—unable to pick up the slack. “We have seen a consolidation of hospital beds in the last twenty years,” says Dr. James McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “Hospitals have gotten increasingly lean and efficient. So a big part of the problem of the pandemic is there is not a huge level of surge capacity in the system to take care of a crisis.”

Health-care companies have spent the past decade pushing for “optimization,” a five-syllable word that can mean both “improving care” and “maximizing profits.” To boost bottom lines that are thinner than one might expect after looking at a medical bill, companies have turned to mergers and acquisitions that have resulted in ever-expanding hospital centers in the state’s biggest cities and disappearing hospitals in smaller towns. The towns around Amarillo are a good example of that contraction. The hospitals in Randall, Hale, and Hall counties all closed between 1998 and 2002. But other rural communities have lost hospitals too. In fact, Texas has seen more rural hospital closures—26—than any other state since 2000. Statewide, from 2010 to 2018, Texas went from about 307 beds per 100,000 residents in acute care hospitals to 279—a decline of 9.1 percent. Especially in a spread-out state like Texas, such a decrease puts patients at greater risk during a crisis.

John Henderson, CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals, says small-town Texas has been suffering death by a thousand cuts over the past decade. “[Rural hospitals] have very low patient volume and very little economy of scale,” he says. “All those things kind of pile up to put a lot of operational pressure on small hospitals, and the result has been closures.”

One of the biggest blows to the bottom line of small hospitals is actually a benefit for patients. Advancements in technology and treatment have led to more patients today being treated as outpatients, who don’t stay the night in the hospital. Fewer overnight patients means less revenue for the hospital operator. In the west-central Texas town of Stamford, the local hospital closed in 2018 partly because it didn’t treat enough patients to qualify for Medicare funding. Medicare requires a hospital to have two inpatients per day, and Stamford Memorial Hospital often averaged less than one per day. The East Texas Medical Center in Trinity, about twenty miles northeast of Huntsville, closed for the same reason, even though it was part of the larger ETMC health-care network.

While these smaller centers of care have been closing, health-care systems in big cities have been expanding as part of their focus on optimization. In the Dallas–Fort Worth area, 23.5 million square feet has been added to various health-care facilities just since 2011, according to an analysis by the Dallas Morning News, with another 20.8 million added in Houston. That expansion is partly to keep pace with the population boom that’s been happening in the state’s biggest cities, but some of the new construction has also been focused on specialty care that can produce big returns for health-care providers. Sandy Schneider, a senior research director at North Shore University Hospital in New York State and a former president of the Irving-based American College of Emergency Physicians, says much of the optimization-driven expansion in health care has focused on “meeting the demands of the public.” American patients, she says, “anticipate near gratification for their ailments,” and hospitals have designed their care around that. In Canada, it’s not uncommon for someone to wait some twelve to eighteen months to get a hip or knee replaced. “In the United States,” Schneider says, “if it takes six weeks to get on the schedule, people are hysterical.”

Health-care companies can make more money by boosting their capacity to provide high-priced, specialty services, but they can also save money by consolidating into larger, urban campuses and sharing the resources at those big, central campuses with smaller hospitals in surrounding communities. That might mean a hospital will buy only a few lithotripsy machines that break up kidney stones and then distribute those machines around their system to wherever there is a patient in need. The push for optimization has led hospitals to eliminate excess beds, which, when empty, produce no revenue. “The bad part of that,” Schneider says, “is that then, across the system, there is less than there was before.” Still, even as hospitals have sought to control their inventory of beds more tightly, they’ve still made plans to quickly boost capacity in a crisis. For instance, a hospital might put two beds in each room in the ICU or treat patients in a cafeteria or chapel.

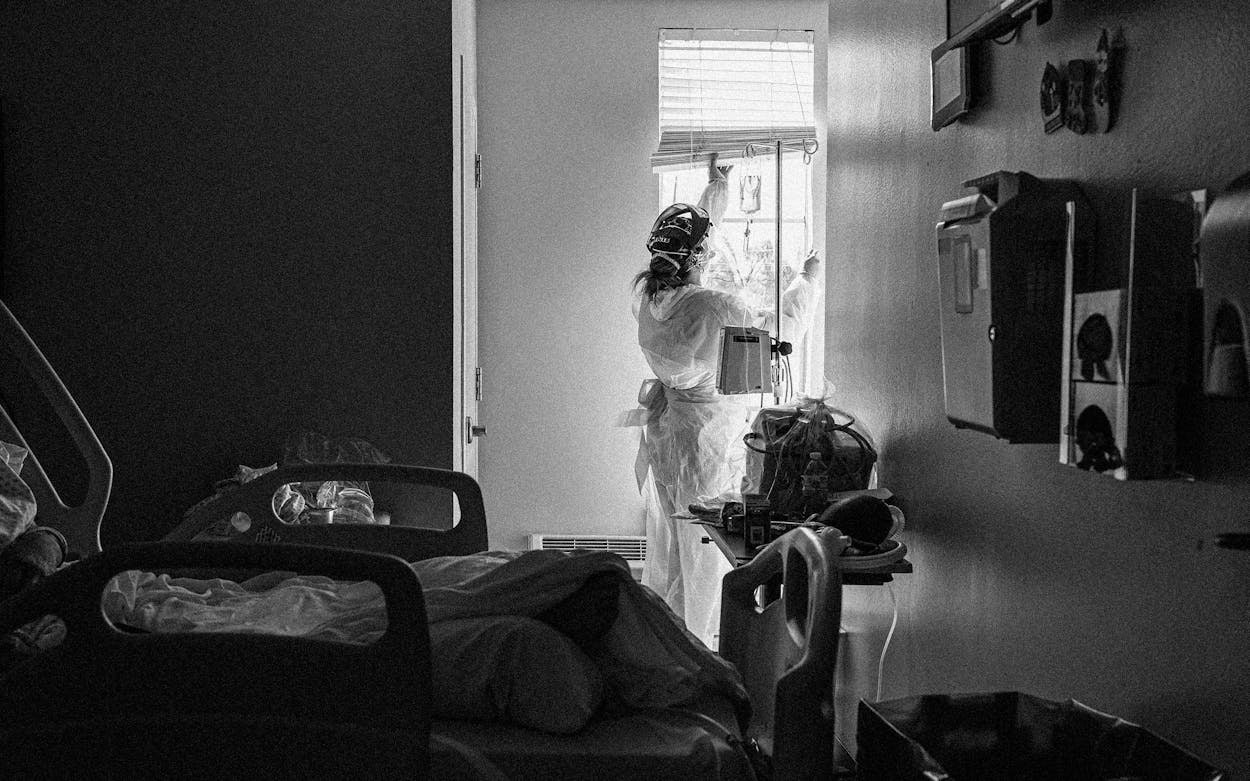

That happened during the pandemic in some places. But staffing problems have kept Texas hospitals from being able to handle the biggest patient surges. The issues started with layoffs in the early days of the pandemic, when quarantine regulations initially caused hospitals to reduce their staffs. When sick patients began showing up en masse, and workers were brought back on the job, not all employees returned. Meanwhile, nurses have been incentivized by high pay to leave and go to work in pandemic hot spots elsewhere in the country. There’s also the burnout of medical personnel after eighteen months working in often brutal, increasingly understaffed conditions, with patients (many of whom refused the vaccine) growing more and more irritable. A study released in September by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 92 percent of hospitalized patients were not fully vaccinated. Some health-care workers have quit or taken early retirement.

By the time the Delta surge rolled around late this summer, capacity at many hospitals was depleted. Justin Fairless, an ER doctor at Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital in Fort Worth, says his hospital was at full capacity back in January 2021. It reached the same level during the Delta surge. Today, the hospital has a smaller staff and therefore less overall capacity to treat patients. Each nurse can cover roughly two people, Fairless says. So, in an eight-bed ICU, if you have eight nurses, you can put an extra bed—and patient—in each room. “Staffing equals beds,” Fairless says. But for hospitals that don’t have full staffing, others have to struggle to make up for the shortage. Fairless says that “chief nursing officers, chief medical officers, health supervisors, charge nurses, and emergency department directors are coming in and working shifts where they ordinarily wouldn’t, just to be that extra body.”

Still, there’s a small silver lining for rural hospitals, amid all the problems of the pandemic. For the first time in more than two decades, Texas has gone a year—almost two, dating to January 2020—without a rural hospital closure. Patient volume is up, and federal stimulus dollars have helped as well. And yet, that may not last. “Most rural hospitals limped into the pandemic,” Henderson says, “and they will be vulnerable again when it’s over.”

- More About:

- Health