This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Better Living Through Chemistry

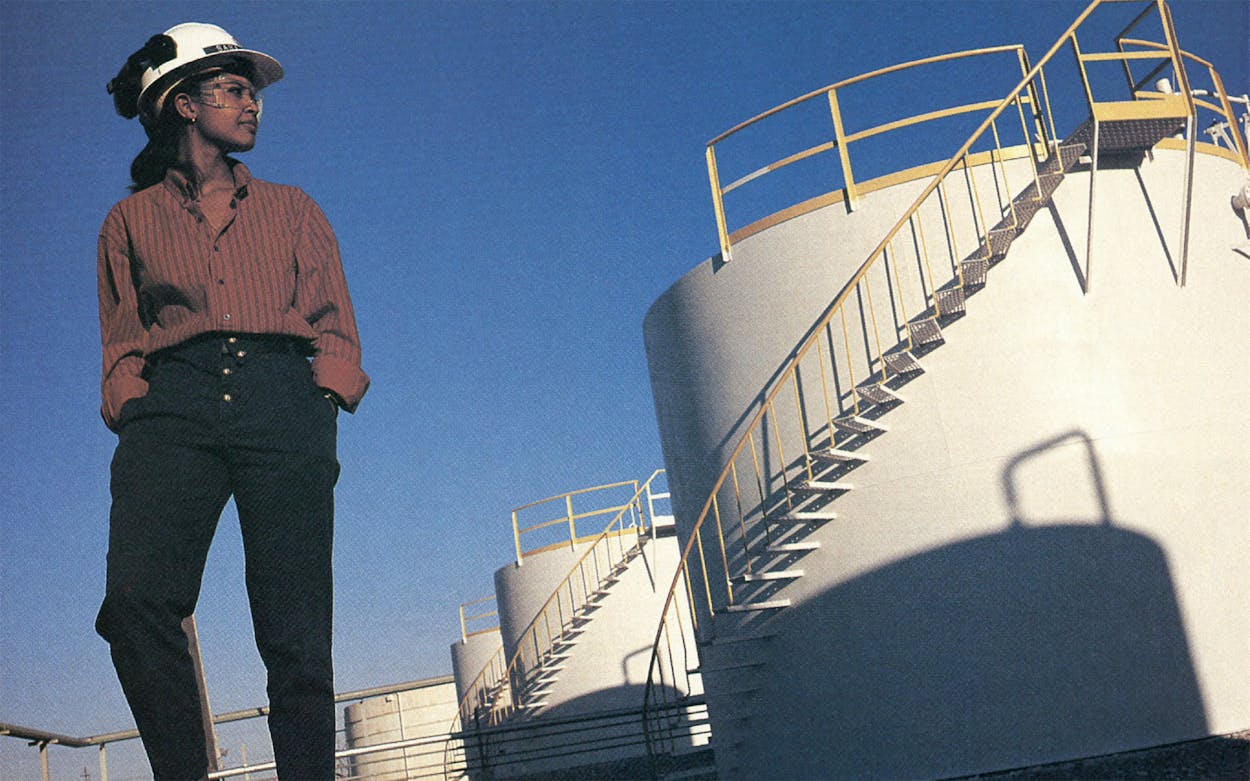

A University of Houston grad engineers her future.

In 1986 a junior majoring in chemical engineering at the University of Houston considered changing her plans. “Refineries were shutting down, people were being laid off,“ Saba Haregot says. “I wondered if I should switch to pre-med. Then I thought that I had invested so much energy in chemical engineering that maybe the economy would have turned around by the time I got out. I took a risk.” By the time Haregot, 23, graduated last spring, the risk had paid off. She had nine job offers, four of them in the Houston area. She is now the process engineer for the propylene-concentration unit at Amoco Chemical in Texas City.

Think of petroleum not as an end product but as a means to an end product. Tons of stuff is made from petroleum derivatives—soft-drink bottles, carpets, microwave cookware, medical equipment. So while the oil business remains down, the chemical industry—the people who buy petroleum to turn it into something else, a very lucrative something else—is enjoying an unexpectedly high upward swing. “We had close to fifty chemical engineers graduate in May,” says Dan Luss, the chairman of the chemical engineering department at the University of Houston. “They all have job offers out their ears.”

They haven’t always. Under the depressed conditions of the past few years, some companies stopped investing in plant improvement and even closed facilities. The word filtered back to young would-be chemical engineers, who—unlike Saba Haregot—decided to try other fields. Then lo and behold, there was not enough product to meet demand, prices shot up, and companies went into a building and hiring frenzy (thus creating the conditions for the next downturn, but let’s not dwell on bummers). For now, Houston is the beneficiary of the world’s belief in better living through chemistry. “There are so many companies in this area,” says Luss. “Houston is a net importer of chemical engineers from around the country.”

Haregot, a small, trim young woman with exquisitely carved features, was born in Ethiopia and went to boarding school in Illinois when she was in the tenth grade. An uncle living there who was a chemical engineer sparked her ambition. “When my uncle talked about towers and pumps, I thought it was so fascinating,” she recalls. “I decided I wanted a hands-on kind of job.” Determined to escape the Midwest winters, she learned about the University of Houston from Lovejoy’s College Guide. “I came to Texas because of the weather,” she says with absolute sincerity. “And I read in the guide that the University of Houston was one of the top ten schools for chemical engineers.

“I just love Houston. All my friends are here. I love to sail, and it’s close to the beach at Galveston. I knew the economy would come back.” When it was time for her to pick from her multitude of offers, Haregot, who now makes a salary in the thirties, turned down more money from another oil company that wanted to move her to Los Angeles.

Walking through the plant in hard hat, safety goggles, and earplugs, Haregot is like a young actress making it on Broadway: she is captivated by the romance of her enterprise. She points to a large tank in which gas is liquefied. “That’s one of my favorite pieces of equipment. When it goes down it’s like a human being—it makes a gasping noise,” she says.

She isn’t worried the cycle will turn, leaving her wishing she were Saba Haregot, M.D. “There are companies out there designing plants for the next ten years. It costs millions to construct a plant.” And surely, she believes, no one would make such a big investment if it wasn’t certain to pay off.

Emily Yoffe

California Leavin’

For gas executives, Houston is the only place to be.

It is five o’clock, and the silver Nissan Maxima is threading its way through the downtown traffic. Inside is Gerald Thurmond, corporate attorney—complete with gray pinstripes, horn-rimmed glasses, leather briefcase, and reserved yet confident manner. Downtown at rush hour is filled with such men in such cars. Yet there is one small but anomalous detail about Thurmond, what the oracles hope is a harbinger of great prosperity to come: Gerald Thurmond’s car has California license plates.

Toward the end of August Thurmond, his wife, and his teenage daughter moved from San Francisco to Houston. Thurmond is the assistant general counsel for natural gas at Chevron U.S.A. At a cost of more than $1 million, the natural gas supply-and-sales division—a staff of 25—has moved from the corporate headquarters in San Francisco to Houston. “We did a survey of the gas business—where it was and where it wasn’t,” Thurmond says. “We concluded it was primarily located in Houston. We were spending an inordinate amount of time flying back and forth, using the Telecopier and express mail.”

While Texans fervently proclaim their obeisance to the great god of diversity, the old gods still keep a tight grip. The simple truth is that good news for the gas industry is good news for Houston. Chevron expects natural gas to be a growing part of the petroleum industry; it is more abundant in the U.S. and cleaner burning than oil. As Chevron realized, Houston is to natural gas what New York is to publishing, Detroit is to cars, and Los Angeles is to movies. It is the place you have to be.

The arrival of people like the Thurmonds is money in the bank for Houston. The family bought a $450,000 brick house in Tanglewood, a well-to-do area about seven miles due west of downtown. They have twice the space they had in their similarly priced townhouse across from the Golden Gate Bridge, although this house won’t be 20 percent more valuable every year, which was the rate of appreciation in San Francisco. Their real estate agent, Anne Bielstein, thinks they got a bargain. At the height of the boom, she estimates, the house would have cost $150,000 more. It had been for sale only two months before the Thurmonds bought it—the equivalent of a nanosecond by Houston’s recent real estate clock. But Anne Bielstein says, “The market has changed tremendously over the last six to nine months. In Tanglewood or Memorial this is not an unusual turnaround time.”

At 52, after six corporate moves, Gerald Thurmond thinks he may finish his career in Houston. “The scenario we’re hearing is that with the environmental questions about the ozone layer, natural gas has a generally rosier future than oil,” he says. “But you know how predictions go. A few years ago oil was supposed to have reached sixty dollars a barrel by 1988.”

E.Y.

Tempered by Time

An oil-field-pipe plant gets a second chance.

Once upon a time, 1981 to be exact, people were willing to pay lots of money for tempered steel pipe they could stick in the ground to see if oil would come out of it. That December some Houston businessmen, eager to extract money from oil seekers, opened a $14 million pipe plant 35 miles west of Houston. Looking back, it’s almost as if the opening of Tubulars Unlimited was the moment that signaled it was time for the bust to start.

At the beginning the descent was gradual. Though the rig count started falling in early 1982, drillers were still sending plenty of steel casing to the plant to be heat-treated at $350 a ton. To temper the pipe took 180 people, including Edward Johnson, who was earning $46,000 a year to manage the plant. That first year everyone thought declining oil prices were just a glitch and that things soon would be back to normal—normal meaning everyone making money like crazy. By 1983 the glitch had become a gulch. Johnson took a voluntary 10 percent pay cut; he was one of the lucky ones—he still had a job.

By 1984 the market’s verdict on Tubulars Unlimited was in. The company declared bankruptcy. Almost immediately new owners saw a great opportunity —a chance to get in at the low end, to be ready for big profits when the oil business turned around. They renamed the plant Temper Industries, but the new name could not change the fact that when people stop drilling for oil, the demand for treated casing evaporates. In December 1986—merry Christmas!—Temper went belly-up, throwing the 25 remaining employees, including Johnson, out of work.

Johnson, now 40, is a Florida native, a burly ex-Marine with tobacco-seasoned vocal cords. He is a classic Texas immigrant, a man attracted here for one reason: work. After his discharge from the service in 1969, Johnson got in his car and started driving around the country. He stopped in Houston, got a construction job, and eventually made his way into a secure industrial job with good benefits. But Houston is about opportunity, not security. In 1981 he took a gamble and signed on to oversee the building of the pipe plant. By that time Johnson was married with two small sons.

Johnson’s personal fortunes have mirrored those of Houston. At the peak of the good years he was making a salary far above the national average and owned a 2,200-square-foot home. But even before the plant closed in 1986, Johnson was in trouble. On his reduced salary he couldn’t make the payments on his house. He sold it in 1985 at a $30,000 loss, and the family became renters. After Texas Commerce Bank foreclosed on the plant, it gave Johnson a small stipend to maintain the equipment. To pay his rent, Johnson did some contracting work repairing houses and his wife did freelance paste-up jobs for printers. Mostly Ed Johnson sent out resumes. Five thousand of them, from Alaska to Australia, seeking a management job in manufacturing. Sometimes he wondered if, way back when, he had stopped his car in the right place.

Then the much maligned market decided to work again. It was one small transaction of the sort that’s bringing Houston up from the depths. The price of the plant had become so outrageously cheap that someone decided to buy it. The buyers were not Houstonians nor Texans nor even Americans. The outsiders with the deep pockets were Canadians. IPSCO, a Canadian steel company that had more than $300 million worth of sales in 1987, was looking for American business opportunities. IPSCO made Texas Commerce Bank an offer it could have refused but probably couldn’t have bettered. The Canadians paid $2.8 million for a plant that had cost five times that to build. Last April Ed Johnson was back at his job at a higher salary than he made in the “good” years. In June he took advantage of the market when he bought a foreclosed house, complete with a pool, for $60,000. “I figured I couldn’t lose,” he says. “My payments are the same as my rent was.”

The day Johnson shows off the plant, the equipment is idle; cobwebs embroider the catwalks. Out back Johnson points to a trailer that once was the shipping office. A fifth of a mile of roadway leads up to it. The area is surrounded by high grass, deserted except for the migrating monarch butterflies that flutter past. Johnson points toward the far end of the road. “At one time we had eighteen-wheelers four abreast out here,” he says, with the look of a man conjuring up glories of a past that seems more mythical than real. “Two hundred and forty trucks a day.”

Johnson doesn’t expect it to be like that again. But the plant’s not going to be turned over to the arachnids either. Johnson has hired five hourly workers, all but one formerly employed by the plant. When they heard the plant was reopening, each contacted Johnson, looking for work. Johnson is supervising the cleanup of the equipment, getting it ready for a fall start-up. He is also training the staff to run every machine in the plant. The workers will move from station to station as they finish the product—there’s no room for specialization in a market that’s willing to pay only $100 to $150 a ton for heat-treated pipe. Of course, Johnson is not going to run the plant with just five workers. He’ll need seven. “Bigger and Better” has been replaced by “Take It Slow.” When the plant was fully staffed, it could turn around a pipe in four days; now it will take nearly eight.

This being the new chastened, realistic Houston, even good news comes with strings. To get the cheapest transmission rate offered by Houston Lighting and Power, IPSCO was told that it must build a nearly $1 million substation for the plant. To which the Canadians responded that they can pick up their plant and take it elsewhere. Terry Buckley, a senior industrial consultant at HL&P, says the company has done everything it can to accommodate IPSCO but it is locked into its rates. Both sides are still negotiating and say they want to work out a solution.

But Ed Johnson is not ready to start thinking about bad news. “My heart and soul were tied up in this plant,” he says. “It was real bad never to see it get a good chance. I think it has that now.” And for the moment, there is a bittersweet ending. Seven people have found good jobs—at a place that used to employ 25 times that number.

E.Y.

- More About:

- Energy

- TM Classics

- Houston