For years, every time James Reyos would leave his small room in an Austin apartment complex, he imagined there was a word on his forehead, flashing like a neon sign. Sometimes it said “GUILTY.” Other times it said “MURDERER.” In his mind, the words would blink on and off as he sat on the bus or walked down the street to go to the convenience store.

Reyos knew he wasn’t a killer—he was a mild-mannered, gay Apache Indian from New Mexico. But back in 1983, Reyos, then a 27-year-old unemployed oil field roustabout, had been convicted of the brutal 1981 murder of an Irish priest in Odessa—even though he had receipts proving that at the time of the killing, he was 215 miles away. He was set free in 1995 for good conduct under the state’s mandatory supervision law but kept getting sent back to prison for parole violations. Over the years, numerous lawyers, journalists, law enforcement officials, and priests had written articles, letters, and legal briefs arguing that he was not guilty of murder. I wrote a few of them too.

But it didn’t matter. To the State of Texas, Reyos was a guilty man.

Yesterday morning, after Reyos took a phone call from his lawyer, Allison Clayton of the Innocence Project of Texas, the words on his forehead finally disappeared. That’s because the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s highest tribunal, ruled Reyos “actually innocent.” It was a rare 9–0 vote by the conservative, law-and-order court, and it came only two months after the trial court in Reyos’s case had recommended he be exonerated. “I’ve never seen a case get flipped so quickly,” said Clayton. The result is that Reyos is exonerated, free of the charges and the verdict.

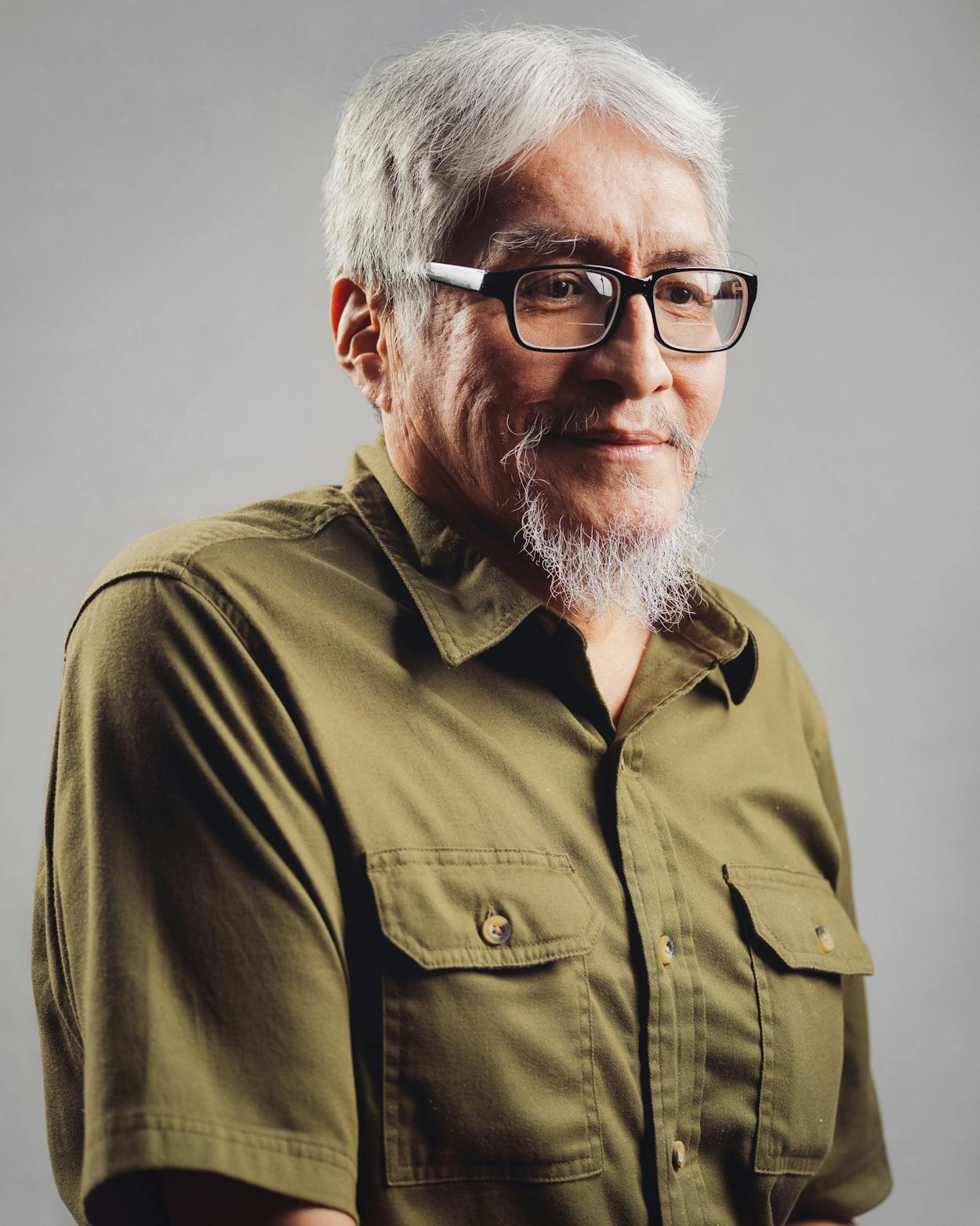

“This is the best day of my life,” he told me when I visited him Wednesday at his apartment complex, a transitional housing facility populated by former convicts. He was smiling but not cheering: Reyos is not a boisterous person. Now 67, he is remarkably calm and steady, with a placid demeanor and a soft voice. His excitement centered on day-to-day matters. “I just gonna sit back and enjoy my total freedom,” he said. “I don’t have to think about going to my parole officer or paying parole fees.”

Reyos’s forty-year struggle to be declared innocent is one of the longest in Texas history—and also one of the strangest. It began with him and a priest, Father Patrick Ryan, meeting for the first time and walking into a bar in Hobbs, New Mexico, in 1981, several hundred miles from the Jicarilla Apache reservation where Reyos grew up. His budding friendship with Ryan led him to be the main suspect when the priest was murdered two weeks later in a hotel in Odessa. Both were closeted homosexuals, and even though Reyos had an ironclad alibi, he confessed to the murder eleven months later in the middle of a shame-filled drug and alcohol binge. That confession was enough for the jury to send him away. After he was released in 1995, he was sent back to jail a few times for alcohol-induced parole violations. He settled in Austin, where he lived in a transitional housing facility.

Then, last year, he finally found help—but only because the children of the Odessa police chief, who took office in 2017, listened to a podcast that cast doubt on the case. The kids asked their dad what was going on, and he got his cops involved. They found fingerprint evidence, long thought to have been destroyed, that pointed to three other men in Ryan’s hotel room that night. The Ector County district attorney investigated the case, and in March Reyos, with Clayton at his side, had a hearing, at which both the police chief and the DA’s office asked the court to exonerate him. Yesterday the CCA made it so.

Now Reyos’s lawyers will file a form with the comptroller so he can get compensation for his years behind bars; he is eligible for more than two million dollars for the years he spent in jail. It’s a pro forma proceeding, as the words “actually innocent” in a decision by the CCA guarantee by statute that he will get the money. For Reyos, who has lived modestly on a fixed income for decades, money was never a priority. He says it might come in handy to buy a house someday, and he’d also like to start a foundation to help those like him research and put together writs for their wrongful convictions. He even has a name for it: the Justice Research Foundation.

Reyos has another, more immediate goal: get clean. The last time I wrote about him, in August, he was behind bars for a public intoxication parole violation. He ultimately spent three months there. He says that his drinking days are behind him and that he’s finally learned his lesson. His father was an alcoholic, so were some of his brothers, and so is he. “I have no desire to drink. My main goal now is to live sober, free, and to just move on, enjoy the rest of my life.” On top of worrying about falling down or getting cirrhosis, he knows that his drinking had a lot to do with why he spent so many of the last 28 years behind bars. “Now I realize that, and I want to live out my remaining years.”

Reyos has long said he wants to return home to New Mexico, to which he has not been able to travel since his conviction—to see his brothers and their families. But he’s not in a hurry. Austin has been home for thirty years. “Eventually I’m going to leave Texas, but for now, I’d like to stay here as long as possible. I have friends here, and I know Austin very well.” He’s friendly with other residents and staff at his complex, and after Wednesday’s ruling, he’s something of a celebrity. All day residents walked up to him and gave him fist bumps or took his photo.

Over the years, the words that gave Reyos the most comfort of all were ones his father had told him forty years ago, right before he was sent away to prison, when courthouse officials had let them have one final visit in a conference room. “Always be strong, son,” his father told him. “Don’t ever give up.” When Reyos got to prison, he wrote those words on a piece of paper and hung it on his cell wall. When he was released, he wrote them on another piece of paper and tacked it to the wall of his small room. Yesterday he brought them up again, proud that he had followed the words of his father. “My life has, you know, it hasn’t been wasted,” he said in his quiet, defiant way. “It’s just gone by without me living life fully, like I really wanted to. But still, I never gave up, despite all the downfalls.”

Disclosure: Texas Monthly has partnered with Deborah Esquenazi to develop a feature documentary on James Reyos.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Austin