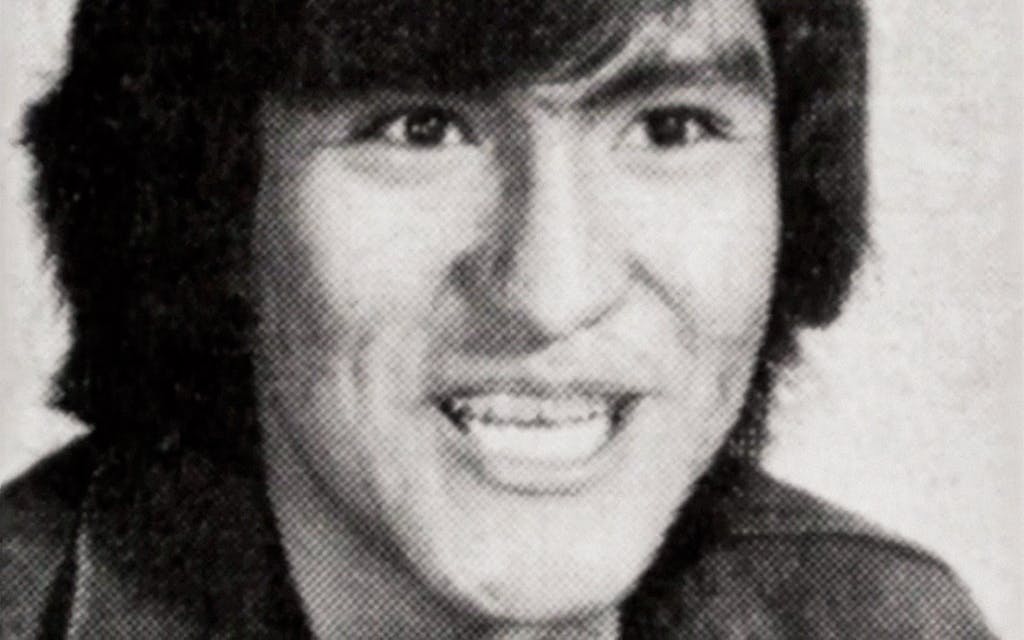

On a warm December afternoon, James Reyos set out from his apartment in Denver City, a small town in the Permian Basin near the New Mexico border, to hitchhike to nearby Hobbs. Reyos, then 25 years old, was short and thin with long black hair. He had grown up on the Jicarilla Apache Nation reservation, in northern New Mexico. Though he’d been in Denver City for about seven months, he didn’t have any friends, and he’d recently been fired from his oil field gig as a roustabout. Reyos struggled with alcoholism and had a habit of not showing up for his shifts. Now he was going to Hobbs to try and find work.

As he walked along Mustang Avenue, a main road on the town’s west side, a red Chrysler with a white top slowed to a stop. The passenger door opened, and Reyos heard a voice: “Where you headed?”

Hobbs, said Reyos.

“I’m heading that way too. Get in.”

The driver introduced himself as John, a Catholic minister. He was older, in his late forties, tall and affable. The two hit it off, talking the entire 36-mile drive. When they got to Hobbs, John suggested they get a drink. They wound up at Tip’s, a local biker bar, where John ordered a pitcher of Coors. The two men fell deeper into conversation; John had grown up in Ireland and done missionary work in Africa, and Reyos told him about growing up on the reservation and working in the oil fields. John seemed genuinely curious about his family and life on the rez. For the first time in years, Reyos felt like he’d made a friend.

After a few hours, John said he had to get back to Denver City, so Reyos caught a ride with him. John parked his car at the local Catholic church. Reyos walked home to his apartment, three blocks away.

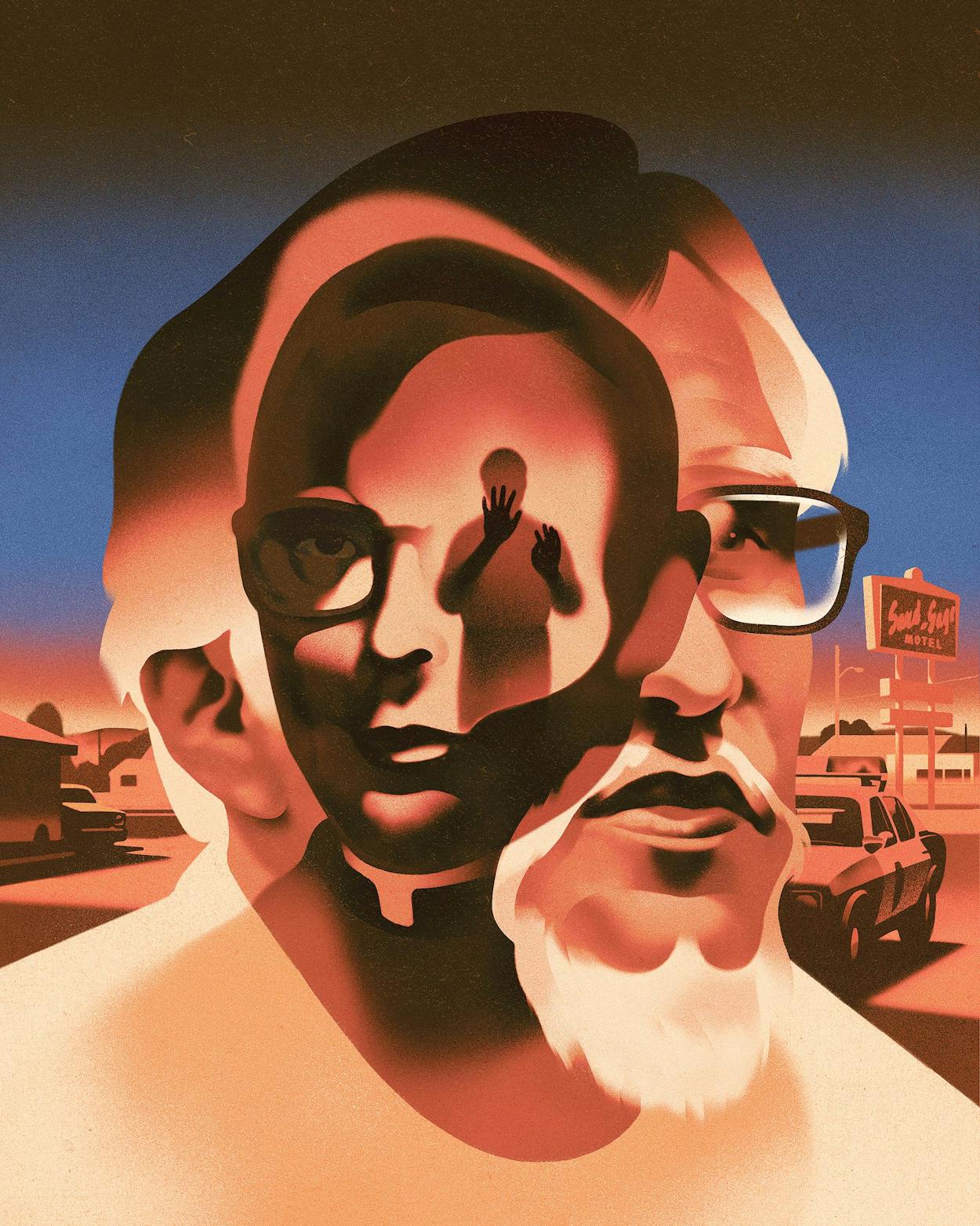

A couple of weeks later—four days before Christmas, in 1981—Odessa police were called to room 126 of the Sand and Sage Motel, where they found a naked man lying face down, hands tied behind his back, dead. His face and body were battered and bloody, and a long slashing wound ran across his buttocks. The room was a shambles: blood on the floor and walls, holes punched in the drywall. The bed was broken and the nightstand was overturned. Cigarette butts lay on the floor, beer cans stood on a bureau, and clothes were strewn across a chair. It looked as if a party had gone terribly wrong.

Officers collected hairs, bloody fingerprints, blood-stained sheets. The pathologist who performed the autopsy reckoned the man’s heart had stopped sometime between 7 p.m. and midnight the day before. He had been beaten to death.

The man had checked into the seedy motel—a place where sex workers conducted a thriving business—under a phony name, so it took a few days to figure out his identity. When the cops finally did, the day after Christmas, they were shocked: he was a Catholic priest. Patrick Ryan, 49 years old, was originally from County Limerick, in Ireland, and had for the previous two years been at St. William Catholic Church, in Denver City, eighty miles north of Odessa. Ryan was passionate about helping the poor and was beloved by his working-class, majority-Hispanic flock. “He reminded you of Saint Francis of Assisi,” said one of his parishioners. Police found Ryan’s car and his wallet outside the Moose Lodge in Hobbs and dusted them for prints.

Police also found a green backpack in Ryan’s Denver City apartment; in it was a photo album belonging to Reyos. When officers brought in Reyos for questioning, he told them that he knew Ryan and that he’d met him when he was hitchhiking.

Reyos admitted to having seen Ryan a few other times too; the father had even lent him money. Reyos said he had been to the priest’s apartment the day before he was killed—Ryan had asked him to bring over the photo album so he could see pictures of his family—and Reyos added that on the morning of the murder, Ryan had driven him to Hobbs so the young man could retrieve his truck, which he had left with a bail bondsman as collateral after being arrested for driving without a license. Nine hours later the priest was dead in Odessa.

While all of this aroused suspicion, Reyos had solid proof that in the hours during which Ryan was killed, he was 215 miles away, in and near Roswell, New Mexico. Reyos had spent that whole day and night and the next morning driving drunkenly around the Roswell area, eventually crashing his truck into a bar ditch. He had a dozen receipts to prove it—for buying gas and then a gas cap, for getting a speeding ticket and then getting towed. Police checked his body for evidence that he had been involved in a violent struggle, but he was clean. None of the hairs or fingerprints found at the scene belonged to Reyos. He was questioned for four hours and passed a lie detector test. Finally, with nothing tying him to the crime, police let Reyos go.

The case went cold. But Reyos found he couldn’t walk away from it. The truth was, he hadn’t told the police everything about his relationship with Ryan. He harbored a secret that was tormenting him: Reyos was a closeted gay man, and it turned out Ryan was too. On Reyos’s visit to Ryan’s apartment the day before the killing, after the two drank beer and vodka and looked through the photo album, Ryan, a big guy at two hundred pounds, had grabbed Reyos and forced him to engage in oral sex.

Nearly eleven months after Ryan’s murder, Reyos, then living in a motel in Albuquerque, was drinking heavily at a bar and took some quaaludes. He passed out, woke up, drank some more, and, after watching an episode of Perry Mason, staggered to a pay phone and called 911. He wanted to talk about the murdered priest in Odessa, he told the emergency operator. When asked who he was, Reyos replied, “You are talking to the killer.”

His confession was enough for an Odessa jury to convict him of murder, in 1983. Ever since, Reyos has fought to exonerate himself, both in prison and out. His forty-plus-year battle to clear his name is one of the longest in Texas history.

When I met him, in January, he was living in a room at a ragged South Austin housing complex, a place filled with dozens of others also transitioning out of prison. The first thing he did was pull out a binder full of articles written about him over the years—in the Dallas Morning News, the El Paso Times, Newsweek, and Out magazine. For Reyos, the binders are a bible of sorts. Inside are letters to three Texas governors and to other officials in which advocates proclaimed his innocence. Also inside is a letter from the murdered priest’s boss, who said Reyos was innocent. And there’s a missive from a man who had once prosecuted Reyos but now wrote that it was objectively impossible for him to have killed the priest. “That is the most important letter right there,” Reyos said.

Reyos is no stereotypical ex-con. He’s five-and-a-half feet tall, with a reserved, almost timid demeanor, and speaks so softly that you sometimes have to lean in to hear him. His hair and goatee are gray, and black glasses frame his impassive face. He had a stroke last September and occasionally has a hard time finding the right words. He moves slowly, often using a walker.

Reyos spent most of his time alone in his small room, listening to old country music (George Jones and Dolly Parton are favorites), reading, writing, and remembering. For Reyos, the past is never far away. On the wall above his bed is a large American flag and a New Mexico license plate. He pulled out a map of his home state and showed me where he had grown up, in Dulce, the mountainous tribal headquarters of the Jicarilla reservation.

Reyos has an abiding sense of calm about him, whether he’s talking about his past struggles or his hopes for the future. He spoke often of his dream of returning home: he longed for the mountains, the snow, his tribe. He wanted to see his three surviving brothers and meet members of his family he’s never known, such as nieces and nephews. But because of restrictions from the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, he’s unable to return.

Reyos has lost almost every battle he’s had with the state. But last November, right after Thanksgiving, he finally won one.

All around him were reminders of why. On his desk sat a framed cover of a 2005 issue of the Austin Chronicle, with a close-up of his face and the words “Murder Mystery.” Above the dresser were a couple of pages from a 1993 story about him. A headline succinctly summarized the last four decades of his life: “Texas vs. Reyos.”

Reyos has lost almost every battle he’s had with the state. But last November, right after Thanksgiving, he finally won one. He was visited in a community room at his complex by his lawyer and an Odessa police detective, who had come all the way from West Texas to tell him that newly discovered fingerprint evidence solidly points to three other men as Ryan’s killers.

Reyos was stunned. It seemed that his life might finally be changing.

Reyos had a typical sixties childhood, riding bikes, hitting baseballs, watching Bonanza on TV. He was the youngest of six children. His father was a petroleum engineer; his mom took care of the kids. The family owned a couple of small cattle ranches, and as a boy Reyos would tag along with his older brothers as they rode horses. “I used to love the cattle drives,” he told me. “Come wintertime we’d move them down south to the winter ranch, where it was warmer, and in the springtime move them back up to the summer ranch.” He told me about a photo he used to have that his mom, who died when he was sixteen, had taken of him during branding season. “I was six or seven years old, and I was holding a calf in a headlock. It had a little white face. My mom loved the Herefords.”

When he was a teenager, in the seventies, Reyos figured out that he was gay. He was terrified to tell anyone, especially his parents and friends. As he would say to a reporter years later, “Apaches were brought up to be brave and strong—and not gay.” He was a quiet teen, a loner, ashamed of his sexuality, afraid of being rejected. He got good grades in high school, but he began drinking beer—a lot of beer—when he went to college, at the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque. He later transferred to Eastern New Mexico State University, in Roswell, to study petroleum technology. He kept mostly to himself; the only times he had sex were when he was drunk. And his drinking got so problematic that he was banned from his dorm. By the time he was jailed for Ryan’s murder, he had been arrested five times for driving while intoxicated and thirty more times for public intoxication.

When Reyos looks back, he knows that his alcohol use had a lot to do with why he was arrested and convicted for killing Ryan. He thinks that his homosexuality and his identity as an Apache likely contributed to the jury verdict too, as did the identity of the victim, a Catholic priest. As a lonely twentysomething living far from home, Reyos made several mistakes, ones that haunt him to this day. To push back against the painful memories of his past, he wrote twelve words on a sheet of paper that hangs above his dresser, a mantra he sees every morning when he wakes up: “I KNOW in my heart—I DID NOT KILL Father Patrick Ryan.”

Reyos doesn’t have a simple answer for why he confessed to something he didn’t do. He recanted his confession the same day he was arrested and taken to the Albuquerque jail. “In the name of God, I didn’t do this,” he told his public defender several times. He told a detective, “I am not the killer. I just like to cause trouble for law enforcement.”

He told me how hard it was being gay back then, constantly fearing rejection, terrified of being exposed. He said his shame consumed him after that night in Ryan’s apartment. “I remember walking down the street afterward, thinking to myself, That didn’t happen. That didn’t happen. I was scared somebody was going to find out.” Eleven months later, drunk and drugged and miserable, he felt somehow responsible for Ryan’s murder: if he hadn’t gone to the priest for a ride to Hobbs to pick up his truck, he thought, Ryan likely would have stayed home at the rectory in Denver City, and he’d still be alive. “It just kept eating at me, eating at me, eating at me. I should have just hitchhiked to Hobbs. I’d done it before.”

At Reyos’s trial, in June 1983, he and his lawyers were certain his solid alibi would save him, especially because he wasn’t the only one leading a hidden life. Two young men testified for the defense that the priest, in civilian garb, had approached them in a parking lot in Hobbs, saying he was looking for “a young stud to f— him.”

But Reyos was doomed by his drunken confession and his story about what happened the night before Ryan was murdered. Reyos testified about drinking with Ryan—first beer, then whiskey and vodka—and said the priest then grabbed him by the shirt collar and forced himself upon him. “I was scared,” Reyos said on the stand. He fell backward during the assault before getting to his feet and fleeing in such a hurry that he left his backpack behind. The next day, he needed a ride to Hobbs to pick up his truck and, friendless, asked Ryan. Reyos said Ryan apologized for the night before and dropped him off in Hobbs around 11:30 a.m. Reyos was newly flush with cash from a quarterly oil-and-gas royalties check from his tribe, and he spent the next day and a half drinking, driving, and sleeping it off.

His lawyer, calling upon a psychology professor for expert testimony, insisted that Reyos had confessed because of the excruciating shame he felt about his homosexuality and the assault. But the prosecutor accused Reyos of fabricating the story about Ryan’s aggression and of slandering the Catholic priest. (It would be another decade before the church’s sex scandals rocked the country.) Reyos was basically outed on the stand in excruciating fashion, as the prosecutor made him recount gritty details about the incident. Reyos had a hard time explaining why he would go back to the priest the next day if he had been so traumatized.

After more than three days of testimony, the jury ignored the Roswell receipts and the lack of physical evidence and found Reyos guilty. Upon hearing the verdict, he went into what he told me was a state of shock. The jury sentenced him to 38 years. One of his defense attorneys, surprised by the verdict, talked to jurors afterward. As he later told a reporter, “They said no one admits to committing a murder if they didn’t do it. That’s what convicted him.” But one of the jurors also told a reporter that the verdict was based on both Reyos’s confession and “characteristics”—clearly a euphemism for his sexuality.

Reyos’s father, who was eighty and using a cane, was allowed to visit his son one last time, in a courthouse conference room, before he was sent away. “Always be strong, son,” he told him. “Don’t ever give up.” When Reyos got to prison, he wrote down the words on a piece of paper and hung it on his cell wall.

At the Coffield Unit, in East Texas, Reyos began gathering documents on his case, helped by family members who made copies for him. He spent hours in the library, studying the law and writing to lawyers and journalists. Though his first appeal, in 1984, was denied, it didn’t take long to get advocates on his side.

One of the first was Bishop Leroy T. Matthiesen, Ryan’s supervisor, who in 1990 wrote to a chaplain at Coffield that he was convinced Reyos was innocent. A year later, Ector County prosecutor Dennis Cadra, who had fought against Reyos’s appeal while working for the district attorney’s office, wrote an eight-page letter to Governor Ann Richards saying that after a careful reading of the trial transcript, he too was now convinced Reyos was innocent. “I came to the firm conclusion that it was physically impossible for Mr. Reyos to have committed the crime,” Cadra wrote, adding that Reyos had several strikes against him in front of that jury, including that he was gay and Native American. Reyos told me he was astonished when he got a copy of the letter. “I remember sitting in my cell reading that letter over and over. I couldn’t believe that a prosecutor had made a one-eighty-degree turn.”

Reyos thought he would get out soon, and he set his mind on returning to New Mexico. When that didn’t happen, he sent a letter to Howard Swindle, an investigative reporter for the Dallas Morning News, asking him to look into his case. Swindle did, and in 1993 published a front-page Sunday story questioning Reyos’s guilt. Two months later, Newsweek wrote about the case too.

Finally, in 1995, twelve years after he was arrested for murder, Reyos was set free under the state’s mandatory supervision law, which required the early release of certain well-behaved inmates. He was allowed to return to New Mexico under his brother’s watch. But Reyos didn’t adapt well to his newfound freedom and was still haunted by Ryan’s murder and by his own sexuality. “I was afraid to get out in the open,” he told me. He began drinking again and was arrested for drunken driving—a parole violation—and sent back to prison in Texas. Behind bars, he spent time as a teacher’s aide and continued to write letters to lawyers and governors—first George W. Bush, then Rick Perry.

In 2003 he was released again. Reyos felt confident that things would finally turn around. His case had been featured in an A&E documentary series, American Justice. It had also caught the attention of state representative Paul Moreno, a Democrat from El Paso, who told Reyos he could help him more if he lived in Austin. So Reyos moved there and got a room at a transitional living facility called the South Austin Market Place, on Ben White Boulevard. He was required to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and meet regularly with his parole officer.

Reyos worked various jobs, including cleaning rooms at an upscale boutique hotel near the University of Texas. His bosses liked him so much they offered him a supervisory position, though he turned it down. One of them later wrote in a letter, “James respectfully declined the promotion only because he soon hopes to see the fruition of his labors to clear his name, and to return to his home in New Mexico.” He also worked as a janitor at his housing facility, cleaning up trash in the parking lot, and at Dance Across Texas, a country nightclub next door.

But Texas authorities weren’t through with him yet. Early on the morning of April 25, 2008, Reyos was stopped by Austin police on his way to work. Officers said a man who fit his description had opened his coat and flashed his genitals at a woman named Alison Sterken. They made Reyos, who denied the accusation, stand in front of her car. Sterken says today she told the cops that although Reyos was dressed like the flasher and, like him, was carrying a flashlight, Reyos was too short by half a foot. “I’m five seven and this person was taller than me,” she told me. “But the cops wouldn’t listen to me. One of them said we were probably standing on uneven ground.”

Reyos was arrested. Although the charges were soon dropped, the incident led to a parole-revocation hearing. Sterken was subpoenaed to testify, and she told the board what she had told the cops: the flasher was much taller than Reyos.

Still, Reyos’s parole was revoked, likely for previous violations that had until then gone unnoticed by parole officers, and again he was sent back to prison. He was now 52. This time he stayed in prison for four years. He got out again in 2012—“a little more bitter about the system,” he told me—and was restricted from leaving the state, so he moved back to South Austin Market Place, into the same small room he rents today.

The complex, now called Common Ground ATX, is a rough-looking place along Texas Highway 71, populated by ex-cons, sex offenders, and former residents of mental health facilities. “There’s good people here,” Reyos told me early this year. “You know, you just gotta watch out who you associate with.”

Occasionally he wanders over to the courtyard and talks to fellow residents, but he mostly keeps to himself, walking to the convenience store to buy ramen noodles or sitting out front and watching the cars zip by on their way to the Austin airport. For years he hasn’t had a cellphone, a car, or a job. A royalty check from his tribe covers his $700 monthly rent.

One of his closest friends is Carlos Patino, the complex’s 62-year-old office manager. Patino is a native of Guanajuato, Mexico, and still speaks with a heavy accent. He’s openly gay and is in many ways Reyos’s opposite: outgoing, exuberant, the kind of hands-on personality who can take care of the daily needs of some one hundred men living on the fringes of society. Most mornings Reyos would wake early, listen to the local news on his radio, go to the dayroom for coffee and a doughnut, and then, when Patino came in to work at 8 a.m., head to the office to visit him. Reyos would tell Patino and others in the office the news of the day, and he and Patino would chat and spar playfully. “We laugh all the time,” Patino told me. “He call me señorita and I call him niña—or señora, because, I say, you are older.”

Afterward Reyos would head back to his room, where he would spend most of his day alone, surrounded by Bible quotes written on scraps of paper and taped to his walls. “Rise up, O Lord my God, vindicate me. Declare me ‘not guilty,’ for you are just,” reads one. Another reads: “Demand justice for me, Lord!”

Occasionally Patino would walk to Reyos’s room and knock on his door. “Niña, you okay?” he would ask. In unguarded moments, Reyos would tell Patino about his ghosts. “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t wake up and think about it,” he said of Ryan’s murder. Reyos was still troubled by the assault on him by someone he trusted—by a priest, of all people. Patino told me he once asked Reyos if he had been in love with Ryan, and Reyos replied, “No, Carlos, I don’t love him, but he was very nice to me.”

Patino learned that there were two versions of his friend. “When he’s not drunk, he’s very quiet,” he told me. But when Reyos drank, he got loud—so loud that his neighbors would complain. Patino said that after Reyos got out in 2012, it was clear something had shifted. Reyos sometimes missed meetings with his parole officer and occasionally showed up for them drunk. In January, Reyos told me he was no longer required to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and that his drinking wasn’t a problem anymore. “I don’t have any craving for alcohol,” he insisted. But sometimes he would catch a bus and head downtown to barhop, wandering Sixth Street and shambling home in the wee hours. He swore he wasn’t interested in finding a partner. “I don’t even think about that now, you know? I’m happy alone. All I have to think about is myself, my fight for justice. That’s my main goal.”

Last fall he was joined in his fight by an unlikely ally: the same office that put him behind bars in the first place. It started when a young woman in Odessa heard a recent episode of the popular Crime Junkie podcast about the Reyos case, which explained Reyos’s airtight alibi and the dearth of evidence tying him to the crime scene. She happened to be the daughter of Michael Gerke, the chief of the Odessa Police Department, and told her father about it. Gerke’s son heard the same episode and also let him know about the case. His curiosity piqued, the chief asked for a copy of the case file. “I got to the end of it,” he told me, “and I went, ‘Well, where’s the rest of it?’ ”

Gerke asked a couple of his men to investigate further. One of them was Sergeant Scottie Smith, who read the file and obtained a copy of a recent book on Reyos by the British writer Scott Lomax, who had been following the case since 2004. “It just didn’t match up,” Smith told me. “There was nothing to put Reyos at the scene. How did they get a conviction?”

Most of the evidence from the case had been destroyed back in 1993, according to department policy, but Smith looked through an old case file and was surprised to find photocopies of latent fingerprint cards, which he showed to a crime-scene tech, Stacy Cannady. She found the actual cards and ran the prints through the Automated Fingerprint Identification System, a national database that didn’t exist in 1983. The result floored her and Smith: the names of two men showed up, neither of whom were Reyos, and investigators soon identified a third figure present at the scene. All three had extensive arrest records on charges ranging from auto theft to assault. The prints of one of the men, who had a long rap sheet, were found on the cruise control knob on Ryan’s car and on a credit card that had been stolen from him.

All three of the men were now dead. But suddenly room 126 of the Sand and Sage Motel looked less like the site of a solitary killing and more like the scene of a murderous brawl.

Smith took everything to the Ector County district attorney’s office, where Greg Barber, the first assistant, was also mystified as to how Reyos had been convicted. Barber, an ex-cop and a longtime prosecutor, says he had never come across a case like this—such an obvious wrongful conviction. “This was new ground for us,” Barber told me. “We didn’t know how to go about correcting it. We wanted to know the best route to make things right.”

Barber had gone to law school at Texas Tech University with Allison Clayton, the deputy director of the Innocence Project of Texas, so he contacted her. Clayton, forty years old and also a law professor at her alma mater, jumped at the chance to represent Reyos. She brought three of her law students to Odessa, all women in their early twenties, and the police put on a PowerPoint presentation of the evidence they had come up with.

By that point, the defense lawyer and the prosecutor were working together to exonerate Reyos. To Clayton, this kind of cooperation was unheard-of: she has helped free or exonerate six men, but she almost always finds herself fighting against the police and the district attorney, who usually want to keep the conviction on the books. “I’ve had prosecutors in counties the size of Ector County tell me, off the record, ‘Yeah, he’s innocent,’ but on the record, ‘We’re going to support every conviction that comes out of this town.’ That’s what I normally see.”

In November, Clayton decided it was time that Reyos heard what was happening with his case. Smith and Barber also wanted to be part of the conversation, so a week after Thanksgiving, Clayton arranged a meeting in one of the community rooms at Common Ground ATX. The lawyer and one of her assistants were there. Smith and Cannady came in from Odessa. Barber and another attorney helping on the case, Carmen Villalobos, phoned in on FaceTime, the cellphone propped against a bag on a table. The acclaimed Austin-based documentary filmmaker Deborah Esquenazi, who had been working on a film about Reyos (which Texas Monthly has joined as a producer), set up a camera.

Reyos sat in an overstuffed brown chair, his walker in front of him, and looked bewildered at those gathered around him. He had no idea what the meeting was about. Clayton, a gregarious lawyer accustomed to speaking in front of large groups, explained to Reyos how they had all come to be there. “We always thought all the evidence in your case had been destroyed,” she said. “But there was actually some evidence that was still around.”

Clayton asked Smith to talk about what the police had found, and the burly cop moved to the couch across from Reyos. “We’ve identified some people that were never mentioned in the report that we can place in that room,” he began. Reyos nodded his head, but the words didn’t fully register. He was still processing the fact that a policeman from Odessa—from the same department that had helped send him to prison—was sitting there talking to him. Smith continued, explaining how officers had taken the fingerprint evidence to the district attorney’s office. “We’re all working together to try and help you.” Reyos thanked Smith, but his face was blank.

“So!” Clayton said brightly. “Here’s where we’re at.” She knelt at Reyos’s side and looked him in the eye. Then she took his hand. “We think we know who really did it.”

Finally, Reyos grasped the gravity of what they were telling him. He reached into his pocket to get a tissue but pulled his hand back empty and began patting his chest slowly. Tears came to his eyes. Clayton drew closer, like a mother comforting her child. After a few seconds, Reyos began repeating the mantra he had held fast to for forty years. “I did not kill Father Ryan,” he said slowly, his words slightly slurred because of his stroke. “I know that in my heart.”

After a pause, Smith said, “With everything that we have in our report, I believe one hundred percent you didn’t do it.” Reyos was finally getting the official validation he had desperately sought for so long. He dabbed at his eyes as Barber piped in from the phone. “The Ector County district attorney’s office believes you’re innocent and is working with Allison to go to court to prove that.”

Reyos nodded. He could barely get any words out. “Thank you,” he said. “Long overdue, but thank you.”

In February, Clayton filed a writ of habeas corpus in the Seventieth District Court, the Odessa jurisdiction where Reyos was convicted forty years ago. The writ argued that he’s “actually innocent,” a legal term for those who can prove, through new evidence, that they didn’t commit the crimes they were convicted of. A hearing was set for the following month.

But as the day drew nearer, Reyos seemed to be falling apart. In early March, Clayton called Common Ground to check in on her client, and Patino told her Reyos was in the hospital. They’d found him passed out in his room with a potentially lethal blood alcohol level of .35 percent. He was released a few days later and returned to his room.

A week after that, and just a week before the hearing, as Clayton and her law school students were preparing in earnest at her office, in Lubbock, the lawyer got a call from Reyos. The team was working around a large table covered with binders and legal documents. Clayton laid the phone on the table and put Reyos on speaker as Esquenazi filmed. It was nine in the morning, and it quickly became clear that Reyos was drunk. Clayton begged Reyos to go into rehab. “I’m worried you’re going to kill yourself,” she implored. “I’m worried that you’re spiraling.”

“I’m spiraling up, not down,” he responded. “I’ll be okay.”

A minute later he confessed, “The reason for all this: what happened to me by Father Ryan is still fresh in my mind. Like it happened yesterday.”

Esquenazi couldn’t believe what she was hearing. “James’s shame cuts so deep,” she told me later. Esquenazi, a gay woman from Houston who also grew up in the closet, often found herself tearing up as she filmed Reyos. “His story is one of the most painful tales of internalized homophobia, shame, and guilt I’ve ever seen.”

Esquenazi drove Reyos to Odessa for his hearing. On March 24, wearing jeans and a bright red sweatshirt, he walked into the courthouse, just a mile from the motel room where Ryan was murdered. Everyone in the building was buzzing about the proceedings, from secretaries to security guards. Everywhere Reyos walked, he was hailed by spectators. “How are you feeling?” one asked. “God bless you,” said another. He was escorted by Clayton’s young, earnest law students. “This is the best day of my life,” one of them told me.

The courtroom looked as if it hadn’t changed in decades: white walls, brown paneling, portraits of judges from years gone by. Three dozen spectators settled onto the benches. At the defense table, Reyos sat between Clayton and Mike Ware, the executive director of the Innocence Project of Texas. The judge, Denn Whalen, was in law school when Ryan was killed in 1981. A Republican district court judge in a conservative, law-and-order county, he seemed moved by Reyos and his case, saying at one point, “I’m not aware of any hearing like this ever taking place in Ector County before.”

Clayton questioned each of the witnesses, and they were unanimous in their opinions. “I don’t believe he committed this crime,” said the police chief, Gerke. “My professional opinion in the case of Mr. Reyos is that he was wrongfully convicted,” said Smith, the Odessa police sergeant. “I see no evidence that he had anything to do with the murder,” said former Texas Ranger Brian Burney, who had been asked by the district attorney to review the case file.

John Smith, one of Reyos’s original trial attorneys, who had gone on to serve as the Ector County district attorney for thirteen years and then as a district judge, spoke about how, even back in 1983, he believed Reyos was innocent. But he and his partner knew they would have trouble winning the case because of Reyos’s sexuality. “In 1983 people looked at homosexuality with a very jaundiced eye,” Smith said. “It was considered a bad thing to be gay.” The verdict still troubled him. “It’s haunted me for forty years.”

Another witness distraught by how the state treated Reyos was Sterken, the woman who was flashed in Austin in 2008. When asked why she had traveled 450 miles from Tyler to testify, she told the courtroom, “I felt a lot of guilt for not speaking up more loudly. I feel like he’s been wrongly treated by the justice system. I want to help right the wrong.”

It’s almost impossible to prove, in legal terms, that an ex-inmate is actually innocent. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s highest criminal tribunal, has described it as a “Herculean task.” But the strength of Reyos’s case became even clearer when Smith and Cannady walked the judge through the new fingerprint evidence. On a giant TV, they showed photos and mug shots of the three men. Bobby Collins, a stocky former Marine, had left a bloody thumbprint on the showerhead. A bloody fingerprint from Charles Burkart, a tall, dark-haired 22-year-old, was found on the door. Gary Ehrman, a long-haired drifter, had left a print on a plastic cup found behind the broken bed.

It turned out that both Collins and Burkart had lived in Odessa in 1981 and that Ehrman, originally from Ohio, had checked into the Sand and Sage with another three guests—an hour after Ryan did. Collins had a record as a violent criminal, and Smith testified that he had talked to one of Collins’s sisters and his daughter, both of whom told the sergeant how ruthless Collins was after returning from a tour in Vietnam. When Smith told Collins’s daughter about the suspicion that her father might have killed a priest, Smith said she told him she wasn’t surprised, adding that he had spent time running drugs in Mexico. “I know he’s killed more people than what he killed in Vietnam,” Smith recounted her saying.

In most actual-innocence hearings, the DA and the defense lawyers are locked in battle, with the prosecutors refusing to admit that their office might have made a mistake. The Odessa hearing was different; the two sides were working together to exonerate Reyos. Throughout the hearing, Barber asked questions that strengthened Reyos’s case. “Everything,” he concluded, “comes back to this: We can’t find a single thing that points to James Reyos. If this came to us now, we’d look at three suspects and not Mr. Reyos. It’s our belief that Mr. Reyos didn’t commit this crime, and we ask the court to exonerate him.”

Clayton eloquently summed up the case. “Father Ryan suffered a horrendous death at the hands of violent, enraged people,” she said. “They completely destroyed a motel room and left their fingerprints behind. We don’t know exactly what happened that night, but the objective evidence proves it couldn’t have been James Reyos. At this point not a single person thinks James Reyos is guilty. He has been suffering for the last forty years.” The courtroom went silent. “He’s a man who’s kind, timid, and didn’t deserve this. We plead that the court would finally bring him some degree of justice and recommend that his conviction be overturned.”

Whalen thanked everyone for testifying, saying that “it gives the court a lot to chew on.” The judge will at some point make an official recommendation to the Court of Criminal Appeals, which has the final say on whether Reyos will be exonerated. The high court has a reputation for taking its time, sometimes years, even in obvious cases like this one.

After the Odessa hearing, Reyos did a series of interviews with reporters and held a press conference. He was closer than ever to vindication, yet he sounded exhausted, speaking even more quietly than usual. He recalled how this building was the last place he had seen his father, back in 1983. The eighty-year-old had attended the trial every day and would sometimes come up behind his son at the defense table and place his hand on his shoulder, a show of silent yet resolute support.

Reyos’s father died a year later, and Reyos wasn’t allowed to attend the funeral. Reyos could still picture him slowly walking away down the courthouse hallway, using a cane, after the two were allowed a final goodbye. He got tears in his eyes thinking about that—and all the other things he’d lost.

Clayton told Reyos that while the legal process ran its course, she could possibly arrange for him to get released from his parole restrictions so he could go home to New Mexico. He told her he would rather wait. “I’m not going to leave Texas until I’m officially considered actually innocent,” he said. “I don’t want to leave Texas until I know I don’t have to come back.”

He returned to his small Austin room, hoping for long-overdue absolution from the state’s highest criminal court. But once he got home and closed the door, he was beset, as he has always been, by demons. On the night of May 5 he hopped on a bus and headed downtown, hitting several bars, staying in at least one of them after hours. By the time he started for home, he was wobbling so badly that he was arrested for public intoxication. His lawyers got the charge, a misdemeanor, dismissed. But because Reyos had racked up several other parole violations over the past decade, he was held for a parole-revocation hearing.

At the hearing, held in Austin shortly before this article went to press, Clayton made the case that Reyos deserved to go free: he was as good as exonerated, so the state shouldn’t send him to prison for violating parole for a murder he didn’t commit. Afterward, Clayton was optimistic, but she knew there was still a chance Reyos would get sent back to prison while he awaits news from the Court of Criminal Appeals.

Ever since his May arrest, Reyos has been living at the Travis County Correctional Complex. I went to visit him a few times, including the day after his sixty-seventh birthday. He was in a wheelchair and moved slowly, sometimes aided by a guard, and wore a gray striped uniform. We sat on either side of a plexiglass window, and he told me he was in the chair because he’d been having dizzy spells when he had to stand for long stretches. He’d lost weight but said he wasn’t experiencing alcohol-withdrawal symptoms. Considering all that he had been through, he seemed in good spirits. From the first time I’d met him, Reyos had impressed me with the placid way he dealt with the world, battling the forces both inside and outside of him. He was ready, he said, for whatever happened next. “I’m not depressed or pessimistic,” he insisted. “I’m optimistic.”

He was still determined to clear his name, and he still dreamed of going home to the mountains of northern New Mexico. He hasn’t seen his brothers in decades, and he wants to visit the graves of his mother and father and his two siblings who died while he was in prison. For years he’s subscribed to the Jicarilla Chieftain, a twice-monthly newspaper that covers Dulce and the reservation. He’d read about elderly members of the tribe living in a retirement community. He thought he might find a place there too. Maybe, he told me, he could even work in the local supermarket, sweeping, mopping, helping people carry groceries to their cars.

It’s a sweet, humble vision, and like so many of Reyos’s dreams, it remains just out of reach.

An abbreviated version of this article was published online on February 3, 2023. It appeared in the September 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Apache, the Priest, and a 40-Year-Old Miscarriage of Justice.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Odessa