This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The bills were falling due for the colossal office-building binge that has transformed the skyline of Manhattan over the past several years. . . . “Today, the rental market is a horror,” says Harry Helmsley. It’s worst in job-depressed downtown, where leasing is minimal. . . . The total loss undoubtedly approaches a billion dollars. Many of the developers who overbuilt so prodigiously are seeing their equity positions wiped out, and as that happens, the overpermissive lenders who backed them may have to step up to the firing line and take title to structures now worth far less than they cost.

—“The Sky Scraping Losses in Manhattan Office Buildings,” Fortune, February 1975

In 1975 the City of New York found itself perilously short of (a) cash and (b) willing lenders. A couple of real estate operators named Joe Gardner and Peter Weisman—whose experience it makes sense to recount because (a) they are emblematic of New York City real estate operators of their time and (b) their office is just around the corner, so to interview them I didn’t have to walk far from (c) my apartment, which they sold me—found themselves in uncomfortable economic straits. Today the City of New York is creditworthy and, as municipalities go, solvent. Today Gardner and Weisman are creditworthy and rich. New York being New York, there is no moral to this story. There is, however, an instructive parallel to life in Texas today. And justice probably demands that if things have turned around so dramatically for New York, where many citizens have an impressive capacity for rudeness, then Texas, whose citizens’ capacity for politeness is matched only by their capacity for optimism, is due for a comeback too.

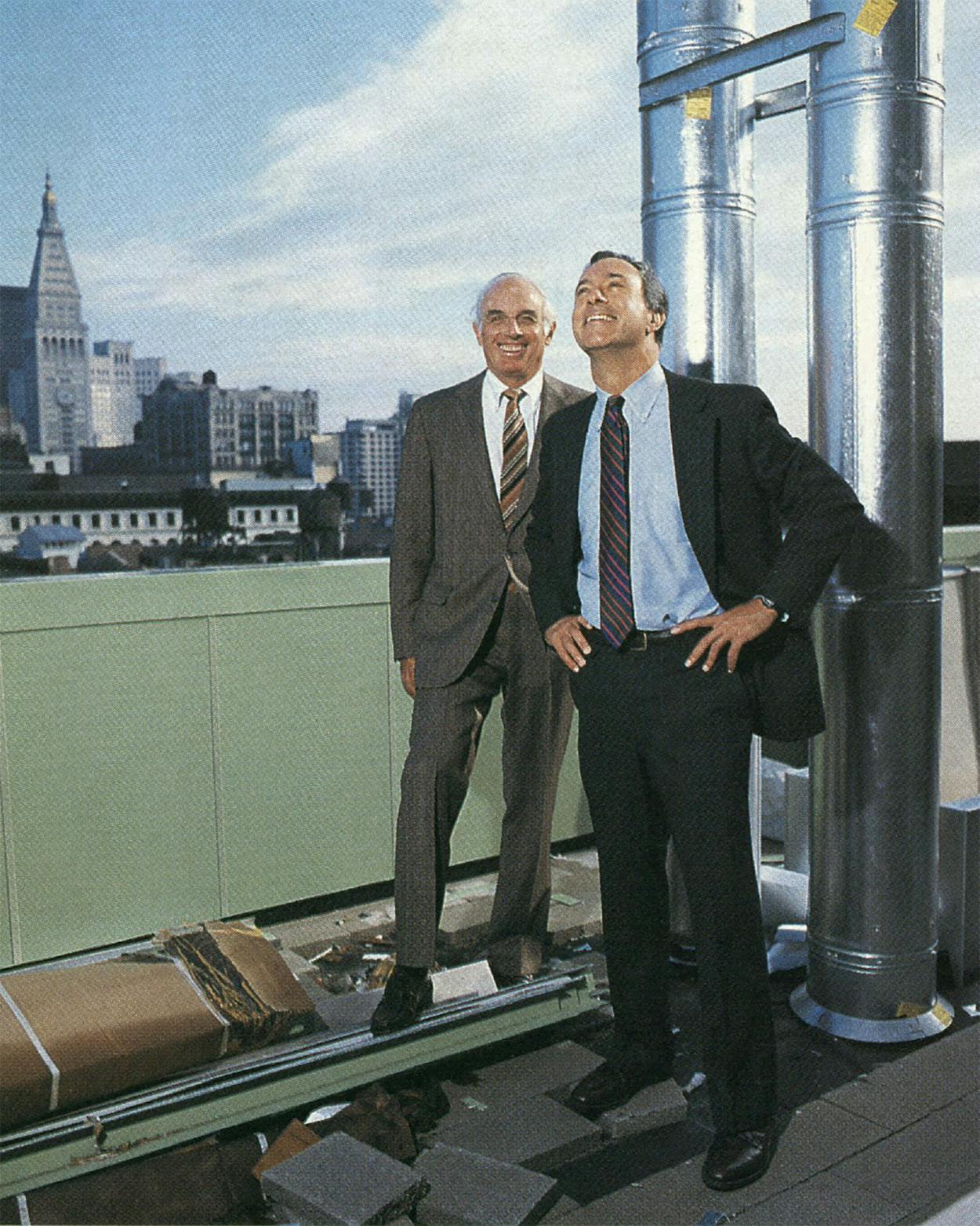

Nice guys, Gardner and Weisman—ambitious enough, aggressive enough, intelligent, occasionally excitable, but generally affable. When they began doing business together in 1968 as P&J Realty, Gardner was an accountant in his early forties and Weisman was an architect in his early thirties. Specializing in renovations—turning neglected or undervalued small properties in unglamorous Manhattan neighborhoods into middle-market apartment buildings—they managed, during their early years, to accumulate some decent assets and some significant debts. Weisman supervised the design work and the contractors; Gardner handled the financial side. Always they endeavored to leverage themselves to the hilt, investing as little of their own money as possible. Whenever anyone would ask P&J’s rate of return, Gardner would answer, “Infinity.”

Instructive Parallel Number One: Let’s say you’re an erstwhile lease broker who has managed to get in debt up to his eyebrows but has neglected to accumulate any assets. Well, next time around don’t do it that way. Bring along some assets. Then, should things turn nasty down the road, throw some assets in the direction of your banker. This will possibly dampen his impulse to test the resiliency of your kneecaps or to put you through a bologna slicer. Try not to get hung up on a narrow definition of “asset.” Surely you own something. Why assume that someone to whom you owe $12 million is incapable of appreciating that something’s intrinsic worth?

“It’s rough times,” says veteran realtor Harry Helmsley. “I went through the Depression and it’s the same dog-eat-dog thing now.” The vacancy rate in Manhattan is now up to 18 percent, the highest since 1939. . . . Worst of all, white-collar employment in the city has actually declined since 1969. . . . As one [developer] says when asked about supply and demand, “all I need is one good tenant.” The trouble is, there aren’t enough such good tenants to go around and probably won’t be.

—Fortune, February 1975

In retrospect, it appears that the market had nudged bottom when P&J in 1975 bought a 50,000-square-foot building, at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Sixteenth Street, whose tenant was a knitting factory. The price was $400,000, and P&J’s deposit on contract was $10,000. Of this amount, $6000 was borrowed from a friend.

“It was doomsday. Everyone was fleeing the city. Only schmucks were buying,” says Gardner.

“Dumb schmucks,” Weisman corrects him.

Instructive Parallel Number Two: In Texas real estate now, the opportunities for dumb schmucks are almost limitless. At least once in your life, pay attention to the right dumb schmuck, and shame on you if you pick the wrong dumb schmuck.

A ghastly possibility, however, hung over the heads of Weisman, Gardner, and their bankers—namely, that the City of New York might default on its debt obligations. One bank made a commitment to P&J for a mortgage loan but not for a construction loan. Another bank, which had verbally agreed to a construction loan, abruptly reneged. In no sense were the bankers behaving unreasonably; if the city was about to go down the tubes, what was to stop the real estate market from going with it? Who needed it? This impasse occurred at a time when P&J owed its subcontractors hundreds of thousands of dollars from a previous job. Without fresh financing, no new project could begin. Without a new project, P&J lacked the means to pay the subcontractors. This meant, quite plainly, that P&J was about to become extinct. This circumstance caused some distress to the developers. To alleviate it, Gardner called a senior bank officer, with whom he had dealt earlier. The banker asked the loan officer whether he had made a verbal commitment to P&J, and the officer admitted he had. So the bank again changed its mind and granted the loan.

The elements of P&J’s little drama were played out on a larger scale later in the year. With New York City facing default, the White House refused to grant federal emergency-loan assistance, and the New York Daily News published its now famous headline, FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. The headline had a galvanizing effect. One thing led to another—I am skipping more than a few details—and eventually there came into being the Municipal Assistance Corporation, a state-controlled entity that in effect put the City of New York into receivership but made it possible for the city government to reenter the credit markets and fund its day-to-day business.

Instructive Parallel Number Three: Texas, stop bragging about your innate greatness, about how you’ll come out of this stronger and better than ever. Just as in the case of New York City, the rest of the country wants to see you humbled. Make things look as bad as possible. Float a rumor that you’re about to go under. Then you might get some help. And quit crying in your Dos Equis that you don’t have a Felix Rohatyn to come down there and crunch numbers for you. Texas has great natural resources—human resources: H. Ross Perot, Willie Nelson, Harvey Martin, my cousin Morris in Lubbock. I bet y’all think of something.

The basic problem, surplus space, is not going to disappear for ten years or more, even if New York’s office jobs start growing strongly again—and the prospects for that are dim.

—Fortune, February 1975

Despite the apocalyptic predictions of an endless real estate bust, what happened next was the unrestrained gentrification of several of Manhattan’s previously unsexy neighborhoods, and Gardner and Weisman were in the vanguard. In place of the knitting factory they created 69 apartments. The first week that the apartments went on the market, a quarter of them were rented. Then, swiftly, the rest were rented. There has never been a vacancy.

Without question, P&J had discovered a new market. As the prospect of municipal bankruptcy faded, New York City once again appeared attractive to the middle class. It was not just painters, sculptors, and fashion designers who were willing to rent or buy a raw half or full floor in a frontier neighborhood. Now it was lawyers, dentists, young execs, socialists with trust funds, and bedraggled journalists.

Today, the same raw space for which P&J had paid $400,000 would go for $5 million. As I’ve said, Gardner and Weisman are rich. They’ve accomplished this by avoiding megalomania and by learning how not to overextend themselves at the bank. Pointing at a calendar from 1979, Gardner says, “From then on we made money.” Of course, so did everyone else who at that time invested in Manhattan real estate.

Instructive Parallel Number Four: Most folks merely got lucky and could just as easily have gotten unlucky. It is better to be lucky than unlucky. If you do manage to stumble across some good luck, never ever assume that you have perpetrated an act of wisdom. In 1979 P&J sold a raw two-thousand-square-foot loft to my wife and me. I’m told we could turn a nice profit should we decide to sell it and buy that big mobile home and those good-as-new pumping units off that fellow we keep hearing from in Borger. If we were wiser—or maybe dumber—we would take him up on it. As my cousin Morris in Lubbock likes to say, “Good judgment comes from experience. Experience comes from bad judgment.”

“The question is how long can the developers take it,” says . . . [the] head of Prudential’s Manhattan real-estate-investment department, “because if they cannot, it is we, their lenders, who are going to be stuck.”

—Fortune, February 1975

For the past decade Gardner and Weisman have diversified in ways that you would have to be from New York to regard as diversification. They have built more rental apartments, and they have built condominiums; they have bought an entire block on Fifth Avenue, where they have renovated a quarter-million square feet of office space; and they have taken rental buildings that they renovated years ago and sold them to the tenants as coops, in the process paying off notes and pocketing more-than-tidy amounts of cash. Most of this activity has transpired in a neighborhood that used to not have a name but is now frequently referred to as “the newly fashionable Flatiron District”—i.e., north of Greenwich Village. Evidently, you become fashionable when you get freshly colonized by advertising agencies, publishers, architecture and design firms, California nouvelle cuisine beaneries, and unpronounceable boutiques.

Instructive Parallel Number Five: I do not think the solution to Texas’ problems is to try to make the state more fashionable. Being fashionable means supporting a bunch of extra overhead. Figure out a way to make Texas smaller. Smaller means scarcer, scarcer means more valuable. And smaller definitely cuts down on your monthly nut.

But it is not the nature of entrepreneurs to dwell for long on gloom. The veterans among them have survived through thick times and thin. . . . “The strong builders will survive this thing,” says developer Harry Helmsley, “but the weaker ones—those without adequate financing—are going to go under.” Because the developers are entrepreneurs and eternal optimists, those that do survive will look beyond the mist toward a brighter future for New York.

—Fortune, February 1975

Ask Joe Gardner, the accountant-turned-real-estate-baron, what he thinks when he reads about the tribulations of, say, a John Connally, the baron-turned-prodigious-debtor, and he will offer an instructive parallel of his own: “The difference between us and those guys is they’re crazy. What Connally was doing was shooting dice.”

Gardner, it seems, has a gift for sensing when the dice are turning cold. In the late seventies he sniffed the wind drifting up from Texas and wangled an introduction to some real decent people from Midland who were successfully drilling gas wells all over Texas and Louisiana (Gardner met these people from Midland through some of his real decent accounting clients). At the time, he and his family were living in a rent-stabilized apartment. In 1981 he finally decided to trade up. For $650,000, he bought a three-bedroom urban Xanadu on Sutton Place. Interest rates were then around 20 per cent, but Gardner was able to cover the mortgage payments with his monthly oil and gas income. Then, as he envisioned P&J’s owning a block on Fifth Avenue, Gardner envisioned himself being strapped for cash. So at the end of 1981 he quit investing new money in oil and gas. Inadvertently, he got out at the peak of the boom. His monthly oil and gas runs—down by 70 per cent—no longer pay the mortgage, but he still has the means to make his payments on time.

Just about everything Gardner and Weisman have laid their hands on since they bought that knitting factory has turned out very nicely indeed. How long can it last? Are there any spare greenbacks in Midland that some real decent people should stick into New York real estate? All businesses are supposed to be cyclical—what goes around is supposed to come around—but this uptick has unusual stamina. It is ten years running now. You think I really know which way it’s headed? If I do, you think I’m telling you?

Mark Singer, author of Funny Money, is a staff writer for the New Yorker.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- New York City

- Architecture