When Jason Garrett returned to Dallas as the Cowboys’ new offensive coordinator, in 2007, he knew even before he began house-hunting that one neighborhood would trump all others: Highland Park. He also knew there was really only one realty office you call when you’re looking for a home in Highland Park: Allie Beth Allman & Associates. And he knew that one realtor rises above them all: Allie Beth herself, no last name necessary.

Cowboys owner Jerry Jones had been a client of Allie Beth’s. Same with Troy Aikman, whom Garrett had backed up at quarterback on Super Bowl–winning squads in the nineties. Allie Beth ended up selling Garrett a handsome three-story neo-traditional French manor with a pool, for a little less than $2 million. Then, about four years later, after Garrett was named the team’s head coach, Allie Beth called to say she had another home he should buy. “I already have a house!” he said. He loved his place, and its four thousand square feet seemed like plenty of room for him and his wife, Brill. They had no children.

“No, no,” Allie Beth said, “this one is better for you.” It had a bigger lot and a more prominent location, closer to the Dallas Country Club and the Highland Park Village shopping center. It would be better for entertaining, she explained. Sure enough, the Garretts bought it three days later, and Allie Beth got their first house under contract with a buyer within 48 hours. She also leased and later sold the home of the outgoing head coach, Wade Phillips, for good measure. In a matter of weeks, she’d engineered a trifecta of major-league real estate transactions. She told her powerful clients what to do, and they heeded her wishes.

The Garretts still live in the house, and Allie Beth, now 83 years old, remains the queen of Highland Park real estate, in a reign that reaches back some four decades. An independent town comprising a little more than two square miles within the boundaries of Dallas, Highland Park is known casually as the Bubble, a reference to its cloistered world of wealth and power. In 2022 Allie Beth’s firm was far and away the number one brokerage in the Park Cities, the area that includes Highland Park and its slightly less prestigious sister community immediately north, University Park. She and her roughly 425 agents tallied more than half a billion dollars in sales last year in the Park Cities alone, more than 34 percent of that market.

Allie Beth Allman & Associates was also the leading broker of home sales of more than $2 million throughout Dallas County (and more than $3 million and $4 million and $5 million). For lower-priced houses and out in the suburbs, the company is all but invisible. The Park Cities and a handful of other wealthy enclaves, including Bluffview, Lakewood, and Preston Hollow, accounts for 75 percent of its sales.

It’s not that there’s no competition; in fact, the battles between brokerages can be fierce, with agents incessantly shuffling between companies on the promise of higher commissions or other perks. But down in the mahogany-

paneled trenches, Allie Beth has long held the advantage; each eye-popping price she secures further burnishes the firm’s reputation and brings more such deals to her and her agents.

Perhaps no property better illustrates Allie Beth’s command of the ultraluxury market than the sprawling Crespi-Hicks estate, in Preston Hollow. The limestone palace is set amid a complex of formal gardens and reportedly once hosted such grand guests as Coco Chanel and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Originally a 10,000-square-foot home, built in the early forties by Pio Crespi, an Italian count and international cotton baron, it ballooned to some 27,000 square feet in the aughts under the ownership of financier Tom Hicks, who at the time also owned the Dallas Stars, the Texas Rangers, and the British soccer team Liverpool FC. In 2013 Hicks decided to sell the estate. Forbes reported the asking price was $135 million—at that point, the most expensive home for sale in the United States.

When Hicks first put the property on the market, he did so with Douglas Newby, a linen-suit-wearing independent broker with a shock of floppy gray hair who has made a name for himself by specializing in what he calls “architecturally significant homes,” and who had represented the estate when the Crespi family sold it. Hicks called Allie Beth, who had helped him buy the house more than a decade before, to explain. “Look, we’re seeing this as a piece of art, and Newby knows all these architectural people,” he said. She told him she understood, but that he should know she would be there whenever he needed her. Which, of course, he did, when the home still hadn’t sold two years later. He gave her the listing after all.

Newby says he received “substantial offers,” but that Hicks’s financial advisers preferred selling the estate in a way that could allow it to be subdivided, at which point Allie Beth took the listing. Billionaire banker Andy Beal bought it in 2016 and auctioned it off the next year to real estate developer Mehrdad Moayedi. He, in turn, parceled off about half of the acreage for development before flipping the remaining property to the Edwin L. Cox family, of the Cox Oil Company. Allie Beth was involved in all of those transactions, turning over one of the lordliest properties in Texas a whopping four times within a couple of decades.

Her sales record speaks for itself. But the continued dominance of Allie Beth and the company she founded seems anything but assured. As Dallas has accelerated its transformation from frontier boomtown into a global city, an influx of new home buyers from the coasts and beyond has attracted new brokers, upending the social order even as new technologies upend the way homes are bought and sold. Meanwhile, storm clouds have parked over the real estate market amid steep inflation, rising interest rates, and the threat of recession. And the ravages of time and competition have fractured Allie Beth’s most valued partnerships in life and in business. The question is not just whether an iconic figure can stay on top in a changed landscape but whether her kind of polite power—a country stoicism she picked up as a girl on the North Texas plains—is still the way to win.

Cambridge, Eton, Oxford. Dartmouth, Harvard, Princeton. Beverly,

Bordeaux, Lexington. The street names of Highland Park read like a roll call of upper-crust establishment destinations, the kinds of places that house heads of state and horse farms. Drawn up around the turn of the last century by the same city planner responsible for Beverly Hills, California, the community was founded as a leafy refuge, complete with a marketing slogan declaring “it’s ten degrees cooler in Highland Park”—thanks to the many trees planted on what had formerly been farmland. (It also, technically, sits at a higher elevation than much of the rest of pancake-flat Dallas, but only by about a hundred feet, hardly enough to look down on the city around it.)

Developer John Armstrong teamed up with his sons-in-law, Hugh Prather and Edgar Flippen, to establish the eclectic mix of European architectural styles that still defines the town—a Tudor here, a Georgian next door, and over there an Italianate villa next to a French chateau. In its first few decades, its most-baronial mansions sprawled along a few key streets, such as those abutting Turtle Creek, while the denser side streets were lined with tidier middle-class affairs.

Southern Methodist University began to sprout just beyond the northeastern corner of the town in 1911, but it was in 1931, with the opening of Highland Park Village, that the area found its emotional and economic heart. While much of the rest of the country was struggling through the Great Depression, the residents of Highland Park were promenading alongside the elegant facades of the Spanish Colonial Revival buildings in the nation’s first-of-its-kind planned shopping center. One lucky winner at the grand opening went home with a pony. Four years later came the Village Theatre, the state’s first suburban luxury movie house, with terrazzo floors and 1,350 seats in a single auditorium, at one end of the plaza.

Drawn up around the turn of the last century by the same city planner responsible for Beverly Hills, California, the community was founded as a leafy refuge, complete with a marketing slogan declaring “it’s ten degrees cooler in Highland Park.”

Today Highland Park Village is perhaps the town’s most literal parallel to Beverly Hills, with a constellation of luxury boutiques—Etro, Fendi, Goyard, Hermès—to rival Rodeo Drive, along with see-and-be-seen restaurants such as Bistro 31 and Café Pacific, where Dallas power players and billionaires (the Bushes! the Joneses!) can dine among their own.

The air of exclusivity isn’t just a feeling. As was common in American communities developed in the first half of the twentieth century, deed restrictions in Highland Park’s early years prohibited members of nonwhite minority groups from owning real estate. Such rules were deemed unenforceable by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948, but it wasn’t until 2003—just twenty years ago—that a Black person bought and lived in a home in Highland Park. The cringeworthy first line of the article announcing this development in the local Park Cities People newspaper: “Guess who’s coming to dinner—and staying for a while.”

Another vestige of this fortress ethos persists in the town’s existence separate from the much larger city that surrounds it. As the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Lawrence Wright wrote in his memoir In the New World, mid-century Dallas became the “Camelot of the right”—a free-for-all for ambitious strivers who didn’t want anything in their way, especially not regulations. Highland Park was a haven amid it, a place where newly minted millionaires could enjoy their money and separate themselves from the hoi polloi. Today many families move to town so that their children can avoid Dallas ISD and enroll instead in one of the state’s best public school districts. And the Highland Park police have a reputation for ticketing outsiders for the slightest infractions while letting residents go.

Perhaps the biggest effect of Highland Park walling itself off has been on the price of its real estate. The tidy colonials and bungalows that once stood on the side streets have been replaced with ever-larger mansions to match those closer to the creek and the golf course. The lots haven’t grown, of course, so today the homes stand shoulder to shoulder like sentries on parade, each craning its neck to stand taller and prouder than the last. The six-thousand-square-foot manors that rose in the eighties and nineties are being replaced or reimagined to include higher ceilings, bigger windows, home theaters, and underground garages with parking lifts. Occasionally, an angular modern creation, all glass and steel, will arise in place of something with Corinthian columns or curlicued ironwork and set the neighborhood aesthetes chattering—which might be precisely the point.

“The house is everything here,” says Candy Evans, the founder of Candy’s Dirt, a blog about North Texas real estate that publishes industry news and gossip along with listings of notable homes. “Your house tells people who you are, who your family is, what you do for a living.” In the toniest parts of Dallas, she says, homes on narrow, deep lots don’t sell as well as houses on wide, shallow ones with more visibility from the street. “Because your home is your castle to show off.”

More than fifteen years ago, Chicago native Evans was working as an editor for D Magazine when she had the idea to start her blog, then called Dallas Dirt, which she took with her when she went solo. Evans began to realize that she’d struck a deep cultural and financial vein and that it wasn’t just the homes that drew her audience. Sure, everybody liked to gawk and dream about what lay behind the sloping lawns and circular drives of the grandest properties—but they also followed the agents and the storylines of the sales. If the trophy homes of Highland Park were fantasy worlds to the masses, the realtors were portals to those worlds. “They’re the movie stars of Dallas,” says Evans.

And Allie Beth Allman became the biggest star of them all.

She grew up Allie Beth McMurtry in the small North Texas town of Graham, about ninety miles northwest of Fort Worth, the second of three daughters of a furniture-store owner and a homemaker who also tended a small farm. Allie Beth was a beauty queen and cheerleader at Texas Christian University, where she majored in radio, television, and film and got to know her distant cousin, Lonesome Dove author Larry McMurtry. To Evans, even today Allie Beth is “the epitome of the Texas ranch girl. You know, get the rifle out, shoot the dinner, cook it. And by the way, I can whip up a dress.”

Allie Beth moved to Dallas in 1962 to take a job as a typist at the radio arm of the local ABC-TV affiliate, WFAA, and there she met the love of her life, Pierce Allman, a program director at the station. A crew-cut SMU grad and former airman in the U.S. Air Force, he’d grown up in Highland Park and at one time was the youngest Eagle Scout in the country, having earned 104 of the 105 merit badges then available. He also had a Forrest Gump–like knack for finding himself at the center of things. About a month after he and Allie Beth wed, he witnessed the president of the United States being shot in the head. Pierce rushed to call the station on that November day in 1963, asking for directions to a pay phone from a man exiting a nearby building: the Texas School Book Depository. The man turned out to be Lee Harvey Oswald. Pierce’s live news report, delivered over the phone moments later, was among the first from the scene that day.

A year later, as Dallas grappled with being labeled by its detractors as the City of Hate, the city that killed Kennedy, Pierce became the director of alumni affairs at SMU, where he built the school’s first alumni directory—a move that would prove useful in business. He later started a PR agency that represented powerful clients such as the State Bar of Texas and the Dallas Bar Association. Pierce steadily got more involved with Highland Park civic life—leading fund-raising efforts and establishing a lecture series at SMU; serving on countless boards for the local museum, library, hospital, and Methodist church; cofounding the local historical society; and on and on. There was hardly anyone in Park Cities society circles who didn’t come to know the handsome couple—Pierce with his boyish smile and Allie Beth with her blond hair shaped meticulously into what could be described as a first lady style.

By the mid-seventies, as Dallas emerged as a seat of new-money power—and the home of America’s Team—Allie Beth had grown close with Alicia Landry, whom she’d met at a Tri Delta sorority alumnae event. Alicia’s husband happened to be Tom, the legendary Cowboys coach. The Landrys were looking to sell their house, and they asked Allie Beth to handle it for them. She wasn’t a licensed agent, but she had recently sold her and Pierce’s house “for sale by owner,” so she figured she could help—unpaid—in the same capacity.

The trust of the coach of the Dallas Cowboys helped Allie Beth trust her gut. Landry didn’t want to be bothered by buyers, so she hosted an open house while he was away at a game. She roped off the room that contained his collection of football trophies and installed her housekeeper, Edie, to stand guard there. When two offers came that day, each for the same money, she showed Landry the contracts when he got home from work and asked him to pick one.

“Which did you like better?” he asked.

“These people,” Allie Beth responded, pointing to one of the papers. Her choice wasn’t based on anything other than personality, but Landry simply leaned down and signed that contract.

“I tell people, just do something,” Allie Beth says now. “You know, don’t wait till you know everything. You’ll never learn anything if you do.” It’s a version of the entrepreneur’s credo—the bias toward action that anchors the mindset of many Silicon Valley CEOs as well as most Texas wildcatters. Allie Beth might not have known it at the time, but she was a born hustler.

Allie Beth Allman & Associates launched in 1985, with one of the most famous names in Dallas already on its client list and with Pierce powering the marketing. “I would never have had my success without Pierce,” Allie Beth likes to say, with characteristic modesty. Pierce brought two critical elements to the company from the start: his peerless network of contacts and his brand-savvy insistence that Allie Beth be the face of the operation.

Over the preceding decade, an oil boom had propelled the Texas economy, spurring wild spending on trophy houses and ranches and helping to turn Dallas into a hub of the banking industry. It came crashing down when oil prices plummeted and credit tightened amid a savings and loan crisis that was national in scope, but with Texas at its center. Real estate values collapsed, and Allie Beth had to scramble to find business for her new company. With many homeowners underwater on their loans, banks started foreclosing—and there she was, ready to help the institutions unload their properties, while at the same time helping families trade down to less expensive homes. “I became the guru of the trades,” she says. “It doesn’t matter where the market is; people have to have a place to live, so you adjust. You figure out a way.” To close a deal in those days, agents sometimes looked beyond the real estate itself and urged sellers to throw in more exotic enticements—a collection of fur coats, say, or a Rolex.

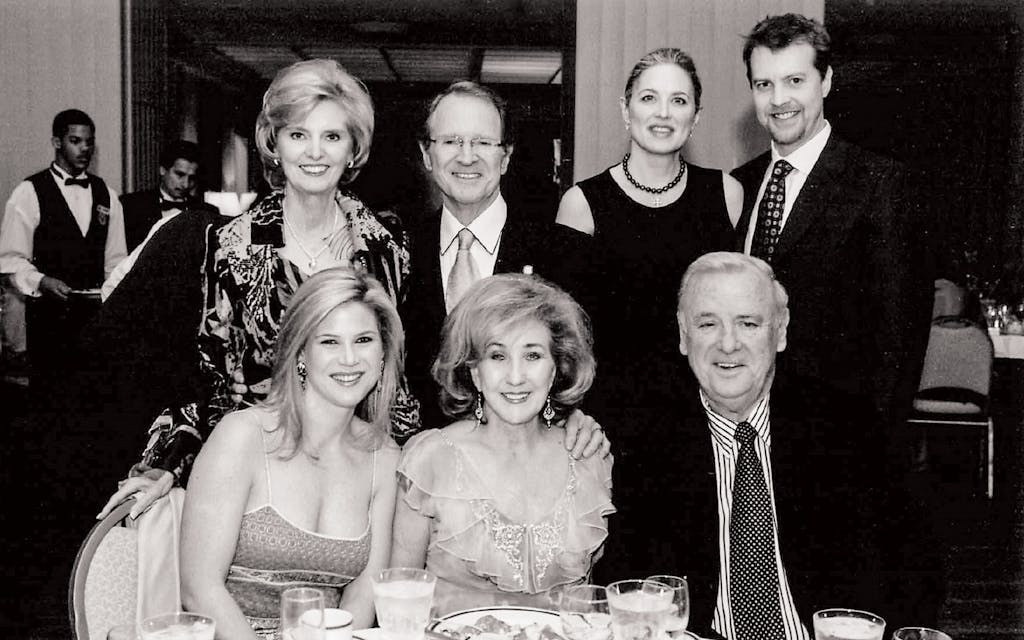

Riding shotgun with Allie Beth early on was another young society maven with a talent for working the angles. Doris Jacobs was five years older than Allie Beth and every bit as ambitious, with her own head of first lady hair (though hers is more often compared to that of former U.S. senator Kay Bailey Hutchison). She developed a reputation for selling houses on one of Highland Park’s most exclusive streets, earning a nickname: the queen of Beverly Drive. Her well-connected husband, Jack Jacobs, had built a chain of local music stores called the Melody Shops that hosted guests including the Rolling Stones and Tiny Tim. He’d earned the nickname “Swinging Jack” and loved a good party—or a poker table or a horse race. Like the Allmans, the Jacobses had two daughters, Teffy and Kim, who grew up with the best of everything. The girls attended the best schools and were debutantes at the best parties, including La Fiesta de las Seis Banderas, an exclusive gala cofounded by none other than Pierce. There were originally six “duchesses” each year at La Fiesta, and each had a doll unveiled in her likeness, custom gown and all.

By the time Henry S. Miller Jr., a local commercial real estate titan who owned Highland Park Village, offered to buy Allie Beth’s firm in 1995, its reputation was impeccable. A few years after the sale went through, Allie Beth stepped away from the business while Doris soldiered on under Miller’s ownership. But after a national real estate company bought out Miller and planned to retire her brand name, Allie Beth decided to come back and start over—with Doris again at her side, this time as a founding partner.

When Allie Beth Allman & Associates relaunched in 2004, in the same building it had always occupied on Tracy Street, at the edge of Highland Park, there was a Texan in the Oval Office, oil prices were climbing, and the Dallas–Fort Worth area was adding some 100,000 new residents every year. Things were good—but nobody could have predicted how much better the market would one day get.

On a sparkling day at the Highland Park Village Starbucks, Candy Evans sips an Iced Passion Tango Tea and details how her blog got the scoop on which house George W. and Laura Bush were buying back in 2008, when they were searching for their post-presidency home. “I remember I was looking for the stories of where people were seeing the Secret Service—you know, the big black car. Where was it? What house was it in front of?” she says. “Well, we found it.” It was an 8,500-square-foot brick ranch house on a cul-de-sac in Preston Hollow, where the president and first lady’s future neighbors would include the likes of Mark Cuban, T. Boone Pickens, and Tom Hicks, then still living at the Crespi estate.

A few hours before Candy’s brag, Douglas Newby had told me, over a plate of truffle and lobster pasta at Café Pacific, that he was the one to discover the Bushes’ home: “I remember I specifically waited until after Thanksgiving, so they could enjoy their Thanksgiving weekend, before I put it on my blog. I said if I were Laura and George Bush, this is where I would probably move, and gave a picture of the house to describe why.”

Regardless of who broke the news, the point is that somewhere along the way, Dallas real estate became the kind of industry that inspires heated competition among gossip bloggers. And Allie Beth, of course, was the one who found the Bushes that house. She and Laura had traversed the area inspecting properties, at times taking off their shoes after treading through flower beds and peering over fences to check out the neighbors’ places and assess privacy.

Houston has oil. Los Angeles has showbiz. New York has fashion and finance. Dallas likes to say it has a diversified economy, but really one industry trumps them all: real estate.

Houston has oil. Los Angeles has showbiz. New York has fashion and finance. Dallas likes to say it has a diversified economy, but really one industry trumps them all: real estate. And gossip—who’s getting divorced, who died, who made or lost a fortune—often fuels it. Gossip can set agents off jockeying for a listing that would emerge if, for instance, a grieving family might need to sell. “Information creates value,” Newby tells me. He and his rivals gather at Café Pacific, where the right table signals who’s important, or around the corner at Bistro 31. At cocktail hour, the younger agents drink at Park House, a private club upstairs at Highland Park Village where, the head of one brokerage told me, “they get drunk and loud and just talk s— about other agents. I call it peacocking.”

Whether it’s the Bush house, the Crespi estate, or anything else setting Highland Park socialites atwitter, it’s a good bet Allie Beth is somewhere near its center—and she knows how to leverage that. One of her favorite anecdotes concerns the day her phone rang and it was the White House, inquiring about her services. “I said, ‘Somebody is teasing me. Who is this?’ And they said, ‘No, we are the White House, and we just want to let you know that Laura Bush is going to be calling you,’ ” she recalls. Today, she and Laura are frequent lunch partners, and during one of our conversations, Allie Beth invited me upstairs to her apartment to see two paintings by the former president—one a portrait of Pierce, the other a prickly pear, both gifts from the artist.

Even that indisputable relationship can bring on a round of sniping from others. Newby makes a point of noting that there are many agents in Dallas who were qualified to represent the Bushes, but “Allie Beth had a daughter who worked in the Bush administration.” Indeed, Amy Allman Dean spent the entire eight years of the Bush presidency working in various roles, including as director of the White House Visitors Office. But so what? Making use of personal connections is one of Allie Beth’s great strengths, and forging those connections is one of the foundations of her success.

She credits Pierce for engineering that. If there was an event in Highland Park, he saw to it that Allie Beth Allman was listed prominently as a sponsor. The Park Cities Fourth of July parade. The elementary school bike rodeo. If there was a board or a committee to serve on, he joined it and quite possibly led it. Doris and Jack focused as much on the social scene. “She goes to every damn social event in town,” says Evans. “You know, you really have to make the phone calls to put deals together, and the way you do that is by knowing people and getting out a lot.”

Keeping score is just crass. Allie Beth has never inserted herself in the top-seller rankings at her company—she just stays out of it. “I never count my money,” she says.

Allie Beth’s clients consistently included the city’s biggest names. Among her listings have been the homes of Dick Cheney, Kay Bailey Hutchison, Ross Perot Jr., T. Boone Pickens, Alex Rodriguez, Randall Stephenson, and many more. For such premium properties, both sellers and buyers often want their transactions to be private, so they’ll sell off market in what’s known as a pocket listing. The general public doesn’t know that the house is for sale; only other agents do. The challenge is that it can be harder to find a buyer. Some agents, Evans tells me, list such properties long enough to drum up interest but pull the listing just before it sells so that there’s no record of what the buyer paid. “That’s for your mega ten-, twenty-, thirty-million-dollar homes,” she says. (This practice violates industry rules, and Allie Beth says she’s never done it.)

To share pocket listings or other market intel, 25 of the most elite agents in Dallas belong to a small group called the Masters of Residential Real Estate. Doris is a member; Allie Beth scoffs at it as little more than a personal branding and scorekeeping exercise. “I don’t want to associate myself with an outside group like that,” she says. And keeping score is just crass. She’s never inserted herself in the top-seller rankings at her company—she just stays out of it. “I never count my money,” she says.

As Allie Beth and Doris were busy tightening their viselike grip on high-end Dallas real estate, one charity gala at a time, an Ivy-educated former New York investment banker named Robert Reffkin saw an opportunity for what the tech and financial elite call “disruption.”

The U.S. housing market is worth a staggering $45 trillion, yet the internet—which had reshaped nearly every facet of society—had largely left the real estate business alone. There were search platforms such as Zillow, and Redfin was emerging as a new kind of tech-first brokerage. But the bread and butter of the industry, the local real estate agent who guides his or her clients through every step of finding or selling a home, still operated much the same as ever, relying on glossy print ads and gut instincts. The company Reffkin launched in 2012, Compass, looked a lot like a traditional brokerage but one equipped with expensive, custom-built technology aimed at making its agents more efficient—what neighborhoods to prioritize, how to market a property, how to price it.

It wasn’t as if other brokers hadn’t discovered the internet, but they invested in modernizing their processes only as their profit margins allowed. Compass, on the other hand, raised heaps of money from venture capital investors and spent it to grow aggressively without worrying about profit in the near term. Reffkin borrowed the land grab strategy employed by the likes of Uber, in which a private company can withstand heavy losses for years as long as it can persuade investors to keep giving it money. That’s done by promising that its technology will prove transformative and by amassing a greater and greater share of the market each quarter. Once the company grows large enough, the theory goes, economies of scale (or perhaps just monopoly power) will allow it to cut costs or raise prices to reach profitability.

Compass found its footing in New York, Los Angeles, Miami, and several other, mostly coastal, areas, before expanding to Dallas–Fort Worth. Reffkin’s start-up raised $400 million in late 2018 and announced plans to enter other fast-growing metropolitan areas, including Austin and Houston. Much as WeWork’s Adam Neumann told the world his firm was fundamentally reinventing the office, Reffkin positioned Compass as the inevitable future of residential real estate sales. He spouted catchy business aphorisms meant to define a better way of working. “No is the killer of dreams,” he liked to say. “No is the killer of great ideas.” He also set an aggressive goal: in the top twenty U.S. cities, 20 percent market share by 2020.

Compass began poaching Dallas agents by offering generous commissions, signing bonuses, and the magic of technology. Among the first targets was Briggs Freeman Sotheby’s, a long-established firm run by Robbie Briggs that was closer to Allie Beth’s in size and clientele than any other. Over the course of several months in 2018, about one hundred Briggs Freeman agents, about 20 percent of its sales force, left for Compass. Among them were the company’s sales manager, Bryan Pacholski, and star agent Amy Detwiler. “Poor Briggs,” says Allie Beth. “I truly feel sorry for Robbie. I really do.”

“Everybody kind of felt bad for Robbie,” remembers Candy Evans, “but what happened to him also woke everyone up.” Going digital was about finding buyers not just for the $2 million properties, the basic unit of Highland Park real estate, but for the rarer $30 million estates. “You want to find some near-billionaire’s attention for that,” says Evans. “You don’t do that by putting a story in the Dallas Morning News. The guy you want is off mountain climbing somewhere and then hopping in his jet and going to the car show in Pebble Beach. He’s on his phone. He understands the tax benefits of having a home in Texas.” You find somebody like that—somebody who might not even live here yet—through the kind of digital marketing prowess that Compass was promising.

Mike DelPrete, a real estate–tech industry analyst and scholar in residence at the University of Colorado Boulder, has studied the rise of Compass in depth and compares the firm to the New York Yankees or the Spanish soccer team Real Madrid—organizations that win by simply buying the best talent. And naturally, if you were raiding the Dallas high-end real estate market for all-star players, you’d go shopping at Allie Beth Allman & Associates. “Compass tried to destroy me,” Allie Beth remembers. This was before it had even raided Briggs Freeman.

Among those targeted on Allie Beth’s team was a young former TCU baseball player named Keith Conlon, whom Compass offered nearly double his pay. What Compass didn’t realize was that, like so many in Highland Park, Conlon had ties to Allie Beth that went deep. After Conlon’s minor-league baseball career fizzled, Pierce had taken him on in a kind of mentorship. Now Allie Beth, who admired Conlon’s “high morals,” was teaching him everything she knew about real estate, grooming him to take over as CEO and president. Neither of her daughters had decided to go into the business—Amy was settled in Washington, and Margaret was raising a family—so Conlon had become something like the son she and Pierce never had. He was inheriting the keys to Allie Beth’s kingdom and was not about to abandon that for a raise.

Even so, Allie Beth knew she needed a wider strategy to withstand a full Compass raid in 2018. Three years earlier, she’d again sold her company, this time to a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway called Home Services of America. The backing of Buffett theoretically gave her access to some of the world’s deepest pockets, but in reality the Omaha billionaire’s businesses have never operated that way; Buffett’s success relies on his famous thriftiness and lengthy time horizons. So simply outspending Compass was out of the question.

One agent who was granted generous Compass stock options told Allie Beth, “I’ll never have another chance to own part of a company like this.” Allie Beth lost that one. But when one of her top sellers was offered a package worth more than a million dollars—including stock, cash, and free advertising—she found her pitch. After pointing out that stock in a company that had yet to turn a profit was potentially worthless, she would patiently explain that relationships were worth a lot—“in Highland Park especially,” she says now. “Our involvement in the community is something that just doesn’t happen overnight. They don’t have that over there [at Compass].” Then she’d prove it. “Someone would call me and say they want to list their house, and I’d call an agent and say, ‘Why don’t you take this one?’ I gave out a lot of referrals that year.”

Giving out referrals is standard practice among experienced real estate

agents, who normally take a cut of the resulting sale while getting their subordinates to do the real work. But a referral from Allie Beth is something else. “It’s a chance to work alongside one of the best that ever did it,” explains Conlon. “That’s a huge enticement even for top agents.” As a way of countering Compass’s truckful of money, it was a bold strategy—not in its flash but in its total lack thereof. Allie Beth was effectively reminding folks that she quietly held a winning hand. And she was arguing that all the promises of digital marketing and precision targeting were a bad proxy for what she, the queen, already had: a reputation.

Amazingly, it more or less worked. Allie Beth Allman & Associates lost about 35 agents to Compass that year and the next—a third of what Briggs-Freeman had lost. “They couldn’t get my agents,” Allie Beth says. But then she betrays a rare crack in the facade, her usual easy twang tensing up as she describes the gauntlet she ran during that period. “I worked harder those two years than I’ve ever worked,” she says. “It’s hard to compete with somebody who’s not playing by the same rules.”

The situation resembled what happened to private-driver services when Uber showed up and undercut that industry. But as any late-stage investor in Uber was learning all too well right about then, the tech start-up strategy of aggressively flooding the zone with cash with no line of sight toward profitability wasn’t necessarily a good long-term bet—even if nobody knew yet how that would play out for Compass. It would require more than gobs of venture capital to take down Allie Beth Allman.

The owner of Bistro 31, Alberto Lombardi—three-piece suit, theatrically tufted silk pocket square—comes over to greet the trio of Jacobs women as they linger over a lunch discussing the past few years’ journey. Doris, at 88, speaks softly, with a slight tremble in her voice, and wears a red blazer not unlike Allie Beth’s. Teffy and Kim flank her at the table, repeating things she doesn’t quite hear and gently running interference when they worry she’s starting to say something too frank in the presence of a reporter. “I will do what I want,” Doris snaps back at one point after one of her daughters admonishes her.

Doris never really learned to use a computer. She keeps an encyclopedic knowledge of Highland Park homes filed away in her brain—when a house was built, who built it, what block it’s on, who has owned it, what they paid, why they sold. It’s helped her sell more than $1 billion of real estate under the Allie Beth banner. Equally important was that the Jacobses long operated as a family business, with Teffy and Kim rounding out the sales force and Jack bringing his decades of entrepreneurial experience to structuring deals in the background.

So when Jack died from pancreatic cancer at age 82, in June 2018, the business cratered. Doris had been Allie Beth’s top seller for thirteen consecutive years, starting in 2004. In recent years, a new crop of superagents such as Erin Mathews, the company’s resident fashionista—whose angular white-blond bob mirrors Vogue editor Anna Wintour’s iconic hairstyle—and Alex Perry, the grandson of three-time Wimbledon champ Fred Perry, had been nipping at her heels. Now, paralyzed by grief, Doris could hardly work. Her sales were in free fall. “She was so lost without Jack,” says Allie Beth.

“Y’all need to get on your roller skates, because you’re going to be so busy, you’re not going to know what to do,” Allie Beth told the troops early in the pandemic.

Doris and the girls had been approached by Compass to defect, but they didn’t go—Allie Beth Allman was simply their professional home, even though Doris had cashed in her ownership stake when the company sold to Warren Buffett. But now, with Doris at her most vulnerable, her loyalty was being tested. A couple of her most prized customers ended up in the hands of Allie Beth Allman & Associates colleagues, high-profile agents whose names nobody will utter on the record. While formal representation contracts typically last only six months, top agents such as Doris tend to have long-standing relationships with important clients that the tight community of direct-competitor agents respect as hers. Some show of deference would be appropriate if one were to take on such a client—even a simple courtesy call. No such thing had happened, and Doris felt like she was being written off.

She, Teffy, and Kim were still trying to rebuild their business when COVID-19 put even more distance between Doris and her clients. The virus also accelerated the migration of out-of-staters to Texas. “Y’all need to get on your roller skates, because you’re going to be so busy, you’re not going to know what to do,” Allie Beth told the troops over Zoom one day early in the pandemic. She’d sensed “doom and gloom” and aimed to quash it. People didn’t have anything to do but look at houses, she figured. And sure enough, 2021 turned into the best year in the company’s history, with $3.8 billion in sales.

Citywide, the price of a single-family home in Dallas jumped more than 50 percent in just five years, from 2017 until 2022. It was a madcap run-up that coincided with the arrival of record numbers of newcomers from the coasts, following myriad corporate relocations and expansions to North Texas—

Charles Schwab, Goldman Sachs, Toyota. That surge in demand led to low housing inventory, shortages of labor and construction materials, and

record-high home prices. The number of Dallas–Fort Worth luxury-home sales, defined as those costing more than $1 million, jumped about 70 percent in 2021 alone, according to Texas A&M’s Texas Real Estate Research Center. In Highland Park, the median home price by that fall approached $3 million.

All of which led, in turn, to another big shot brokerage coming to Dallas with designs on raiding the talent pool: Douglas Elliman, which had made its reputation selling some of the glitziest properties in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami. The firm became nationally famous when one of its top agents landed a gig as the star of Million Dollar Listing New York, a reality-TV show on Bravo.

Whereas Compass wooed agents with the magic of technology, Elliman’s pitch relied on playing up its glamorous reputation, its ties to showbiz, and the promise of first dibs on the country’s most coveted buyers: those fleeing California and New York, as well as international buyers from London and beyond. The CEO of its Texas operation, Jacob Sudhoff, was a Corpus Christi native who’d rocketed to real estate riches in Houston after getting his start in the business at the age of sixteen.

One of the early agents Sudhoff lured to Elliman was a man of Indian descent named Andy Anand, who had grown up in Toronto and moved to the state to play football at the University of North Texas. As a member of the Sikh faith, Anand wears his hair long and tucks it up into an elegant turban, known as a pagri. “When I met Andy, he was wearing a baseball cap, trying to hide his heritage,” remembers Sudhoff, who advised him to wear the turban proudly—but with designer suits—the better to connect with the city’s newly booming population of well-to-do South Asians. When they later learned that the turban was acting as a competitive disadvantage in one potential deal, they paired Anand with Breah Brown, a white former Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, who stood in as his front woman. “Andy didn’t care about being the face of anything,” Sudhoff says. “He cares about money.”

That was in 2021. Several months later, in April 2022, Keith Conlon got a call from Doris late at night on Easter Sunday—late enough that he was in bed and she left a message asking him to call on his way to the office the next day. When he called her back, she dropped a bombshell.

“I was just letting you know we’re going to Douglas Elliman,” she said.

“Did you leave Allie Beth a message too?” he asked, gobsmacked.

“I was hoping you could tell her,” she said.

It was unthinkable to Conlon that forty years of close friendship and business partnership could end so abruptly. “She never even came and tried to negotiate,” he remembers. “She just called up one day and said, ‘I’m out.’ It was wild.”

Candy Evans ran a breathless item on her blog about the queen of Beverly Drive splitting from the queen of Highland Park. It began by noting that “selling real estate may look easy, but it’s one of the toughest, most brutal, and often the loneliest occupations out there. You eat what you kill, you compete with sharks on an hourly basis, you are rejected 24/7, and you run your own business as an independent contractor.” And Doris, the item concluded, is “one of the hardest-working agents God has ever created.”

With Jack gone, Doris knew that maintaining the family business was increasingly going to fall to Teffy and Kim. Elliman offered an opportunity to build a brand around the Jacobs name, with Doris officially a team leader and her daughters under her, plus tens of thousands of dollars in free advertising—though nothing close to the extravagant offers Compass had been making three years earlier. Perhaps the greatest enticement to go to Elliman was the sense that it was new and shiny, in a city where those are prized virtues.

The news stung Allie Beth. In her eighties and vulnerable to COVID, she had spent much of the pandemic keeping her distance from the office and, worse, from her clients. She’d handed day-to-day control to Conlon, only to watch the firm come under attack not once but twice from newcomers in the market. Her old friend Jack had died. And now this shocking news from her stalwart business partner. “I’ve been with her from day one—it’s heartbreaking for me,” she told me not long after the announcement. “But, you know, we’ll make it, with or without her.”

On top of it all, her beloved Pierce was struggling with his health after a diagnosis of the neurological disorder hydrocephalus. Where once the couple had delighted in charming visitors with their stories, effortlessly passing the narrative back and forth like two sides of one brain, Allie Beth now had to be selective about who could even come to see her ailing husband. More often, the Allmans didn’t see anyone, remaining confined to the penthouse, where Allie Beth became Pierce’s doting caregiver.

On a Tuesday early last December, an unmarked black SUV with dark-tinted windows sat outside the neo-Gothic Highland Park United Methodist Church, as two Secret Service agents with earpieces stood by. Inside the church, nearly one thousand mourners—a roll call of Highland Park luminaries—filed quietly to their seats to await the funeral of Pierce Morriss Allman. Allie Beth sat in the front row, flanked by her daughters and their families. Troy Aikman was there; so were Jason and Brill Garrett. There was Laura Bush too, though George W. was out of town. (“The Bushes were the first people who came to see me after Pierce died,” Allie Beth would tell me later.)

The eight months since Doris had announced she was leaving had been a roller coaster. In the spring of 2022, home sales continued climbing to previously unimagined heights. But by that summer, with inflation likewise rising, the Fed launched an aggressive campaign of interest-rate hikes, effectively throwing a bucket of cold water on home buyers who’d grown used to easy money. In neighborhoods such as Highland Park and Preston Hollow, the effect may not have been quite as pronounced, because ultrawealthy buyers tend to pay cash rather than use traditional bank financing. Still, even when those buyers close a deal with cash, they tend to use debt of some form in the background, because amassing the debt is cheaper than forgoing potential investment gains on their cash elsewhere. What’s more, even in Highland Park, many of the smaller homes—mere four-thousand-square-foot mansions, not sprawling estates—fall in a price range that makes sense for regular old mortgages.

In Dallas’s premium neighborhoods, the number of homes for sale plummeted while the average price shot through the ceiling—especially because fewer of the more modest homes were selling, leaving a disproportionate number of the wildly expensive ones. By December 2022, while the overall market was reeling, the median listing price in Highland Park approached $5 million—more than double the figure from just a year earlier. That, of course, is a market tailor-made for the likes of Allie Beth Allman and Doris Jacobs.

The trouble was that they were both preoccupied. As Allie Beth had contended with Pierce’s declining health over the course of the year, Doris hadn’t found Douglas Elliman to be the home she’d hoped it would be. More than anything, it wasn’t a good culture fit. It was brash, versus the quiet confidence of Allie Beth Allman & Associates. It was the difference between getting loaded upstairs at the Park House and lunching at Café Pacific.

One day that July, an agent called Allie Beth to say she’d been speaking with Doris. “Allie Beth, Doris is miserable,” she said. “You need to call her.” For decades, Doris had popped into Allie Beth’s office whenever she was feeling down, and her old friend would buck her up with a few calm words of encouragement. “She didn’t have me those two years [during COVID], so she thought I didn’t love her,” Allie Beth says. “The company she went to just catered to her—they gave her some attention.” The master networker realized she had neglected one of her closest friends.

That afternoon Doris, Teffy, and Kim went to Allie Beth’s condo, and they talked for hours. Allie Beth explained that caring for Pierce had been an isolating experience, on top of the COVID isolation everyone was going through. She emphasized that Keith Conlon was firmly in command of the day-to-day operations now, and she rarely went to the office. “I’m very sorry if I hurt your feelings,” she said. “You were one of my first agents. You are glued to my company, and I just have to have you.”

“She came back to me,” Doris told me later.

Just three months after they’d left the firm, Doris, Teffy, and Kim returned to Allie Beth Allman & Associates, this time officially as a team. Candy’s Dirt ran an item that quoted Doris saying she “just couldn’t leave” Allie Beth. “It was like leaving home.”

Pierce entered hospice in November, and the Jacobs trio spent a lot of time with Allie Beth and her family in the weeks leading up to his death. At the funeral, they were sitting a few rows behind Allie Beth, near the front of the cross-shaped sanctuary. The Reverend S. M. Wright II, a pastor from South Dallas and son of a legendary civil rights leader, read the Lord’s Prayer. Pierce had served on the board of a foundation established in Wright’s father’s name to serve underprivileged families. A succession of speakers talked about the values the Allmans represented over their 59 years together. Pierce was a patriot and a man of discipline and manners who was eager to understand others’ perspectives. He learned to slalom water-ski at age seventy. He read the newspaper out loud to Allie Beth every morning.

After the service, the SMU Mustang Band—“the best dressed band in the land”—appeared just outside the doors of a reception hall on the church grounds in their full red, white, and blue regalia. They played the “SMU Loyalty Song”—whose lyrics Pierce wrote for them back in mid-sixties—as guests filed in to join a receiving line and greet Allie Beth. At the front, alone, in sturdy heels and an immaculately tailored black dress, she offered a firm handshake, a quiet smile, and a few words to each guest, as if she were there to comfort them. She stood there for three hours.

If there were any doubt about whether Doris was truly back in action coming into this year, the Doris Jacobs Group website argues to put that to rest. Next to a picture of Doris in a smart red jacket, a short blurb about her services begins, in bold, “Doris Jacobs is the only name to know in Dallas real estate.”

She sold a $15 million house late last December to a couple from California. They’d already bought a lot to build on, because the house they really wanted wasn’t for sale—but then Doris heard through the Masters of Residential Real Estate that it was coming up as a pocket listing and gave the hopeful buyers a ring. They put in an offer that night.

It was among three $14 million–plus deals that month at Allie Beth Allman & Associates—one of the other two having been made by Allie Beth herself. The firm also has the listing for the Crespi-Hicks estate, which came up for sale again this spring. But this time another agent, a close friend of the owner, is handling the deal, with Allie Beth advising.

Allie Beth doesn’t dwell on her deals, but she does find time to dwell on Compass. “I just feel sorry for the people who went over there thinking they were going to be rich,” she says, “because the stock is in terrible shape.” Indeed, when the company went public in April 2021, its stock debuted at just over $20 and then began a steady slide as inflation picked up, interest rates rose, and concern mounted that Compass had managed to lose money in the hottest market anyone could remember. The stock price has hovered at under $5 since last June, rendering those agent incentive packages virtually worthless. Mike DelPrete, the real estate industry analyst, wrote that the business would be “unsustainable” without severe cost cutting.

Allie Beth avoids using Compass founder Robert Reffkin’s name. “I would tell my agents the guy, the founder, he was like the Music Man,” she says, unable to stop herself from gloating a bit. “He came into town, blew his whistle, and said, ‘I’m just wonderful. You’re all gonna be rich!’ But you cannot pay out that kind of money and get a return when it’s too good to be true.”

Allie Beth doesn’t dwell on her deals, but she does find time to dwell on Compass. “I just feel sorry for the people who went over there thinking they were going to

be rich,” she says.

Compass’s Bryan Pacholski points out that the company has nonetheless grown into the largest brokerage nationwide and in Texas, with more than eight hundred agents in Dallas–Fort Worth. “Over one thousand agents have come to Compass since August 2022 for no cash sign-on bonuses or stock,” he adds. And the firm has managed to amass a sizable market share in Dallas, particularly at the high end. By last summer, when its stock price finally stopped sliding, it was second only to Allie Beth Allman & Associates in almost every measurement of Dallas-area luxury sales. In some of the more mass-luxury measures—such as number of sales above $2 million in all of Dallas County—Compass was even dangerously close to passing Allie Beth. But in the kingdom of Highland Park, Allie Beth’s lead remained far greater—34 percent of the market to Compass’s 21 percent. If Compass can hang on to the top agents it lured over, it will remain a force in Dallas.

The same can’t be said of Douglas Elliman, which, at the end of last year, had a little more than 2 percent of the Park Cities market. Douglas Newby, who’s watched the brokerage battles up close for decades, isn’t surprised. “I have seen other companies and people come to Dallas from California or New York thinking they would wow everyone because they were big in L.A. and end up being pretty much ignored,” he says. “People think, ‘What’s so big about an L.A. agent? Everyone is leaving L.A. anyway. If they can’t keep their clients there, what are they contributing here?’ ”

It’s not that Dallas society is a stuffy club that shuns outsiders, he believes, but rather that people here sniff out and reject coastal elitism. “I can’t emphasize enough that Dallas is not an old-school, uncrackable, inbred environment,” Newby says. “This is the most open city in the country. You have third- and fourth-generation important families, and you also have new wealth, and you have people moving here. They might enjoy going to New York for the museums and culture, and they might have a vacation home in Santa Barbara or Malibu. But nobody that is seeking out Dallas lives in awe of L.A. They are not impressed.”

All of which leaves Allie Beth still firmly in charge of the Dallas luxury market. “She’s the Energizer bunny,” as Candy Evans puts it. Allie Beth, more than anyone, knows how to handle an economic downturn; it’s how she got her start, way back in the days of the savings and loan crisis. And in any case, even with the slowdown of 2022 and the looming possibility of a recession in 2023, Dallas–Fort Worth remains one of the strongest real estate markets in the country.

“It’s really my outlet since my husband died,” Allie Beth says of her work. “I’m so lucky to have something that I love that I can get back to. I hope I die showing a house.”

One day, of course, someone else will occupy her throne. One name that fuels a lot of speculation is Amy Detwiler, the Briggs-Freeman defector to Compass who inspired others to follow. Maybe Teffy and Kim Jacobs will emerge from their mother’s shadow, or maybe Allie Beth’s handpicked successor as CEO, Keith Conlon, will grow into a dominant force in his own right.

Or perhaps the next Allie Beth will look entirely different and bring an entirely fresh perspective—someone like Elliman’s Andy Anand, whose sales volume today is nowhere near that of the industry giants but who represents changes in the market that the existing social order might not even yet recognize. Anand sold his first Highland Park property, a $6 million home, to a pair of Pakistani American doctors, in November.

Allie Beth thinks the new Allie Beth has yet to emerge—that it’ll be somebody who strikes out on their own, “somebody who builds a company,” she says. “It has to be.” There are lots of great salespeople in Dallas. But Allie Beth was always more than that. As Doris Jacobs might be the first to attest, it’s one thing to be the top seller, the queen of Beverly Drive, the name to know. It’s another thing to be Allie Beth Allman.

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Queen of Highland Park.” Subscribe today.