All of us have done things we regret, and one of the things I regret deeply is my treatment of Frances Tarlton “Sissy” Farenthold at a dinner buffet I gave in honor of a writer friend. Everyone was assembled at my house except the guest of honor, who was still signing books across town. As these things go, she was late—it was around 9 p.m.—and guests were hovering around the Mexican buffet in our dining room like starving hyenas. It was Sissy who finally came up to me and asked, not too patiently, if it wasn’t time to start serving. In a burst of confusion, childlike rebellion, and just plain lack of common sense, my answer was no.

Every time I think about that moment, I fall into a micro-depression. What could have possessed me to tell Sissy Farenthold that she couldn’t dig into the enchiladas? To insult a woman I had admired my entire life, an icon of Texas feminists?

Over decades of private shame I have pondered the answers to these questions, and especially since her death on Sunday, from complications related to Parkinson’s disease. I’ve considered the kind of woman Farenthold was—a Texas legend, to be sure, but not the kind most often honored here. A few examples of the latter would be other Texas women in the first-name-only club: Ann (Richards) and Molly (Ivins). Ann and Molly created a sense of intimacy with their humor—they brought you in on the joke. No one particularly cared that the jokes were cover for a roiling anger—both women understood intuitively that their humor could be used to draw listeners in and (maybe) change a few minds. Sissy believed that persistence and anger and truth were enough to bring reform to Texas, and, before Ivins and Richards, she almost did it.

Given the current state of our politics, it’s hard to remember that era, back in the early seventies, when a dark-haired mother of five with an undergraduate degree from Vassar and a law degree from the University of Texas started convincing voters it was time for a change. Desperately shy, she still managed to win election to the Texas House in 1968, the first woman to represent her district, based around Corpus Christi, in the Lege. She started causing trouble right away, refusing to support a resolution praising former president Lyndon Johnson. Pretty quickly, it got better or worse, depending on your persuasion, when Farenthold and 29 Republicans and other Democrats—read that again: Republicans and Democrats—became known as the “Dirty Thirty” for taking on corruption, in particular on the part of House Speaker Gus Mutscher, who was eventually convicted of bribery in what was then known as the Sharpstown scandal.

By 1972, Farenthold, pondering her next move, was getting letters from the likes of one Ann Richards urging her to run for attorney general. “There is no question in my mind that the time for election of a woman to statewide office is ripe in Texas.”

Farenthold didn’t take Richard’s advice. Instead, she ran for governor. “Our present state leaders have run Texas like a cash register,” she declared in a campaign commercial that is nearly unimaginable today. “The governor profits from the Sharpstown stock swindle. The lieutenant governor makes a fortune on private deals with special interests. Another candidate is a banker who is a back-up man for the big-business interests. It’s time to take Texas from the special interests.”

Farenthold beat the incumbent governor Preston Smith and golden boy Ben Barnes in the Democratic primary but lost to wealthy, middle-of-the-road rancher Dolph Briscoe in a runoff. Still, Farenthold’s race had boosted her national profile: at the Democratic Convention in Miami in the summer of 1972, she was placed in nomination as vice president and received the second most votes. She had met with Bella Abzug, Betty Friedan, and Gloria Steinem in the ladies’ room of the Miami convention center to determine who would put Farenthold’s name into nomination. Her declaration in the lobby of the Doral Hotel was inspiring, if in retrospect naive: “As a woman, I alone could appeal to the women of all parties. By November 1972, the women voters of this country will outnumber the men by a margin of eight million votes. Women will probably remain the voting majority for the rest of the century. I believe it is time this majority has representation at all levels of government, including the Democratic vice presidential nominee.” The Texas delegation, led by future governor Briscoe, did not support her.

George McGovern’s final choice, and probably the only one he ever really took seriously, was Senator Thomas Eagleton, who ended up leaving the race after it was discovered he had undergone shock treatment for depression. Farenthold’s profile, in contrast, continued to soar. “The Ticket that Might Have Been” was the cover line on Ms. Magazine’s January 1973 issue, which featured Farenthold and Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress. That same year, Farenthold was elected as the first chair of the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Ever hopeful, Farenthold came home to run against Briscoe again in 1974. She lost again. At 48, she walked away from public office, serving as president of Wells College, in New York, from 1976 to 1980, and then practicing law in Houston. But Farenthold never stopped working for change: women’s rights and nuclear disarmament, as well as justice for victims of human rights violations in Iraq and Central America.

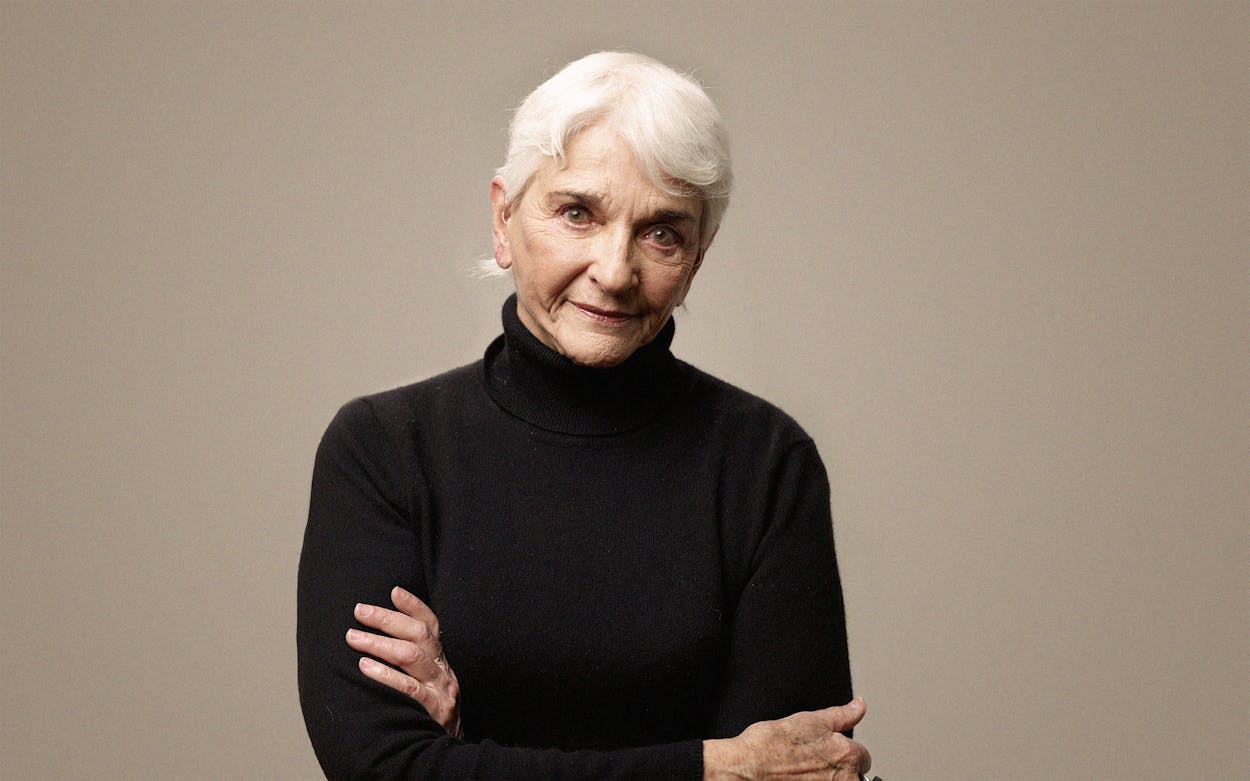

Over time, her black hair turned white, and she cut it short, so that she resembled a penitent pixie. Sacrifices had been made: a divorce in 1985, the death of a three-year-old son, and the loss of a son, who disappeared in 1989 and has never been found. Writing about Farenthold in the Texas Observer, Molly Ivins called her “a melancholy rebel,” which seemed about right.

Except that, to the end, she was starchy too. Her progressive beliefs, formed when she served as head of the Nueces County Legal Aid Program in the mid- to late 1960s and saw how benign neglect left so many mired in poverty, never wavered. Farenthold stuck with “people’s lawyer” Jim Mattox when Ann Richards ran against him for governor in 1990, and she refused to support Hillary Clinton’s presidential bids because of Clinton’s support for the Iraq War. Farenthold was enthralled with Bernie Sanders and his bid to rein in the power of Wall Street. For Farenthold, there was never any gentle if expedient stroll back to the middle.

She wasn’t Molly, and she wasn’t Ann—she wasn’t an entertainer—and that may be why Sissy will never be quite as beloved or admired. Still, she stuck to her guns in the way of the best Texas women. She knew who she was, what she believed, and what was important—and for that reason deserves to maintain her place beside them.

If I ever got the opportunity to serve her enchiladas again while they were still hot, I’d have done it in a heartbeat, in gratitude for all she did for women like me.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature