Mayra Flores, a respiratory therapist and political novice, made history this month, winning a special congressional election to become the second Republican since Reconstruction to represent parts of the Rio Grande Valley in Washington, D.C. Many Democrats saw Flores’s win as yet another ominous sign that their long dominance of South Texas politics may be coming to an end. But not Gilberto Hinojosa, the leader of the state Democratic party. Shortly after the election was called, Hinojosa released a statement dismissing the loss as a meaningless fluke.

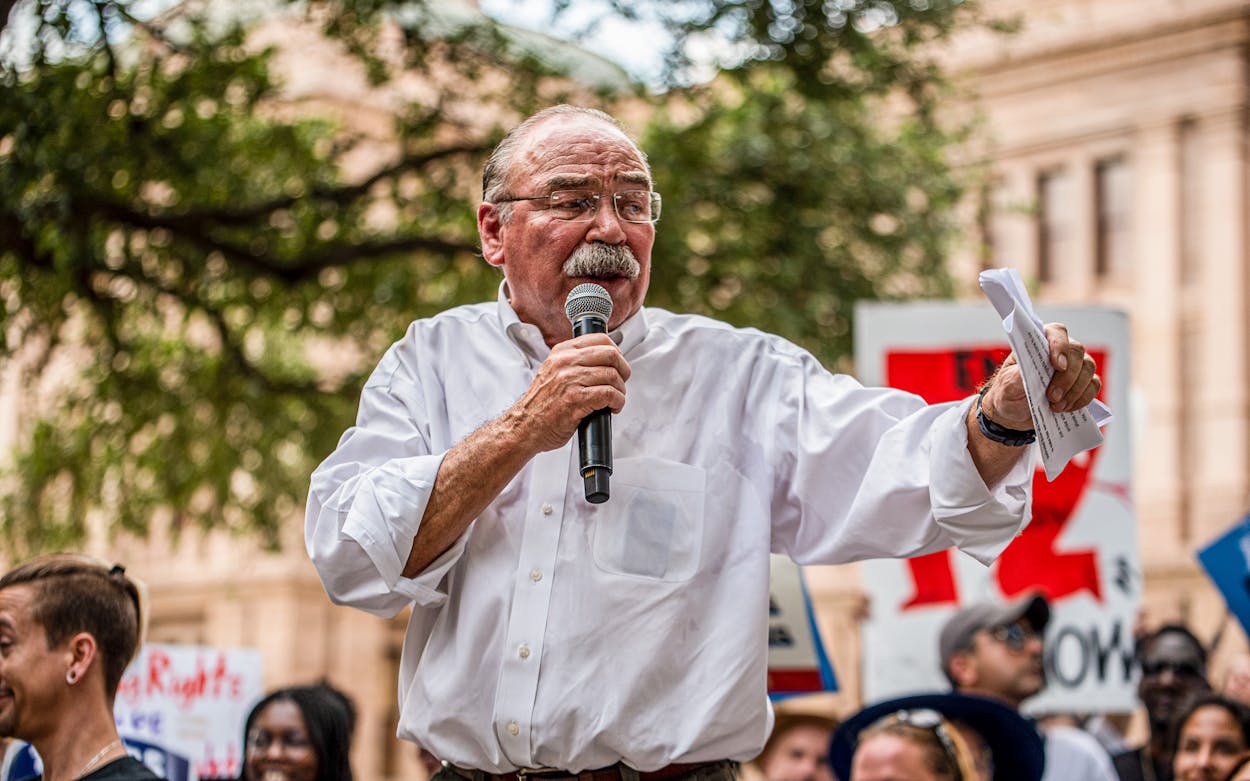

“Despite flooding South Texas with over three million dollars in far-right dark money—in a special election called by the Governor at a time specifically chosen to give Republicans an overwhelming advantage—Republicans could barely squeak out a win,” wrote the 69-year-old Brownsville attorney, who has served as chair of the state party since 2012. Hinojosa noted that Flores would have to run again in November to win a full term. “This seat,” he promised, “will rightfully return to Democratic hands.”

The statement seemed to encapsulate the odd combination of complacency, magical thinking, and blind belief in demographic destiny that has characterized the Texas Democratic Party for years. (It was also misleading—the reason Abbott called a special election was because Democratic congressman Filemon Vela abruptly retired in the middle of his term to take a lucrative job at the largest lobbying group in the U.S.) Hinojosa’s blustery show of confidence was especially puzzling given the party’s three-decade-long record of futility and failure. No Democrat has won a statewide race since 1994—the longest drought for any state party in the country—and Republicans have held a majority in both chambers of the state Legislature since 2003. While Democrats control five of the state’s six largest cities, and have enjoyed some recent success in the suburbs, they remain about as popular as rattlesnakes in the rest of Texas. Most worrisome of all, Republicans have been making inroads in the formerly deep blue Rio Grande Valley, as demonstrated by Flores’s win and Donald Trump’s gains there in 2020.

Yet to hear Hinojosa tell it, the party has never been in better shape. In the wake of the 2020 election, he bragged that Democrats had raised more money and turned out more voters than ever before—never mind that the party had once again failed to win a single significant race. “Any pundit who claims ‘Democrats lost Texas’ can’t see the forest for the trees,” Hinojosa told a reporter three days after the election.

But the Democrats did lose Texas. And the only person who couldn’t seem to see it was Hinojosa. “We cannot keep calling failure success—this is not Orwell’s 1984,” said Carroll Robinson, a Houston law professor and chair of the Texas Coalition of Black Democrats. Robinson is one of two candidates hoping to unseat Hinojosa in July at the state party convention in Dallas. The sixty-year-old attorney told me that he threw his hat in the ring because, after spending half his life in Texas Democratic politics, he was tired of losing. “Our job is winning,” he recently wrote in an email to supporters, “not pretending to win by bragging about losing.”

The other candidate for party chair is Kim Olson, a 64-year-old retired Air Force pilot who now lives on a ranch in Palo Pinto County, an hour’s drive west of Fort Worth. Olson was the 2018 Democratic nominee for agriculture commissioner and came within five points of beating incumbent Republican Sid Miller. In 2020, she ran for Congress, winning a plurality of votes in the primary but losing the runoff. Olson said she’s challenging Hinojosa because he has systematically neglected rural counties such as hers. She told me that 40 of Texas’s 254 counties don’t have a party chair, and in 170 countries Democrats are fielding just a single candidate in this year’s local elections. (A spokesperson for Hinojosa disputed those numbers, but when asked for the correct ones said he didn’t have them.) “It is the county parties that get voters out the door,” she said. “It is the county parties that understand who should run. There’s not a soul in the bubble of Austin that gets anybody in Palo Pinto County to vote.”

Hinojosa still has plenty of supporters. Born in Alamo, on the U.S.-Mexico border, Hinojosa earned a law degree from Georgetown University and worked as a civil rights attorney in Washington, D.C., before returning to South Texas to launch his political career. He became a local power broker, working his way up from Brownsville school trustee to Cameron County judge, the county’s top executive. In 2012, he was elected chair of the Texas Democratic Party two years after it suffered historically bad election results. Spurred by hatred of President Barack Obama, the insurgent tea party had infused fresh blood into the staid Bush-era GOP, sweeping a new generation of Republicans into power across the state and wiping the few remaining centrist Democrats off the map. When Hinojosa was elected chair, Republicans enjoyed a supermajority in the Texas House, holding 102 seats to the Democrats’ 48. This meant, humiliatingly, that Republicans could reach the quorum necessary to take votes without even a single Democrat present.

As chair, Hinojosa immediately turned the party’s longtime strategy on its head. Rather than continuing to pursue centrist voters, who had been flocking to the GOP for decades, the Democrats would instead focus on inspiring and turning out their base. “The party’s philosophy before I came in had been that we had lost a lot of voters to the Republican party, and the way to become a blue state again was to bring those voters back,” Hinojosa told Texas Monthly in a recent phone interview. “I came to the conclusion early on that that wasn’t going happen, that the people who left the party weren’t coming back—at least not then.” In hopes of winning back those voters, the party had adopted fence-straddling positions on issues such as gay marriage and gun rights. Under Hinojosa, Texas Democrats became the first state party in the South to endorse marriage equality, along with a host of other progressive positions.

None of the eleven operatives, activists, and candidates I interviewed disputed that the party has improved in almost every measurable respect over the past decade. “Texas has become a battleground state, and that was under chairman Hinojosa’s leadership,” said Manny Garcia, who served as the party’s executive director from 2019 to 2021. “He brought us out of the wilderness and into national prominence.” Ali Zaidi, the 2022 campaign manager for two-time Democratic lieutenant governor nominee Mike Collier (who lost to Dan Patrick by fewer than five points in 2018), said that Hinojosa “took nothing and made it into something.”

But the question facing Democratic delegates at this month’s convention is whether Hinojosa, having turned nothing into something, is capable of producing the one thing that has eluded Democrats for nearly three decades: a victory for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, or any other statewide elective office.

Hinojosa may have taken the party out of the wilderness, but it’s still a long way from the promised land. In 2020, Texas Democrats convinced themselves—and the national party—that they could flip John Cornyn’s U.S. Senate seat and as many as twelve U.S. House seats, and perhaps were in striking distance of a Texas House majority too—all thanks to what they described as favorable demographic trends. Democratic candidates raised nearly $200 million, more than in any previous election cycle. The stakes were particularly high because whichever party controlled the Legislature would control the once-a-decade redistricting process that occurs after every U.S. census. Past Republican-led legislatures had pushed gerrymandering to its limits to draw themselves maps that locked in their majority; now they looked set to do it again—unless Democrats flipped nine seats and took control of the state House.

The party was confident it could flip those seats—and more. Throughout the election, Hinojosa seemed convinced that the Democratic presidential nominee was going to win Texas for the first time since 1976. “Texas will go to Joe Biden,” Hinojosa promised a reporter in September 2020. “Texas is the biggest battleground state in the country,” he declared later that month. He wasn’t the only one making these forecasts—Beto O’Rourke told a reporter the same month that Texas was “Joe Biden’s to lose”—but as party chair and a DNC executive committee member, Hinojosa’s words carried the most weight. And out-of-staters listened. Biden dispatched vice-presidential candidate Kamala Harris to campaign in Texas, and the national party funneled tens of millions of dollars into local races.

In the end, it all came to naught. Trump won comfortably, though by a smaller margin than in 2016. Cornyn held off Democratic challenger MJ Hegar—who had raised nearly $30 million—by a whopping ten points. Most damning of all, Democrats didn’t pick up a single seat among the nine they had targeted in the Texas House. The failure rankled liberal activists and donors, many of whom felt misled by Hinojosa’s rosy projections of Democratic triumph. It didn’t help when, in the aftermath of the defeat, Hinojosa boasted that the party had turned out more Democratic voters than any state except California—no big surprise or accomplishment, given that Texas is the country’s second-most-populous state.

“A party chair, to a certain degree, has a responsibility to talk up the party,” said longtime Democratic strategist Matt Angle, founder and director of the Lone Star Project, a Democratic organizing group. “But I don’t think it’s responsible to telegraph wins. The worst thing Democrats can do is hold pep rallies saying we’re about to flip the state.”

Robinson, the Houston attorney running for party chair, had a more pungent way of describing Hinojosa’s rhetoric. “It’s bullshit,” he said. “We did not do what we needed to do in 2020, which was to gain ground in state House races and flip the state for Biden. You can’t be so prideful that you’re unwilling to talk about what happened.” Olson, Hinojosa’s other challenger for state chair, was just as blunt: “We got our asses kicked. And what happened? Donors said, ‘To hell with you—we’re closing our checkbooks.’ Trust me, that’s a quote.”

It’s easy to understand why Hinojosa tells donors what they want to hear. Everyone wants to back a winner, while few enjoy squandering money on a lost cause. But when your rhetoric becomes so divorced from reality that you start sounding like a Soviet bureaucrat, others stop taking you seriously. “Donors began to say, look, this is pouring money down a rathole,” said Southern Methodist University political scientist Cal Jillson. “‘We can’t just keep doing this, because the party doesn’t win.’ And so the major donors sort of went quiet.”

Since November 2020, Hinojosa and every other Democratic strategist have been trying to figure out what went wrong. The party is quick to point the finger at Biden, whose presidential campaign issued an edict forbidding door-knocking during the 2020 campaign to avoid having election workers accidentally spread COVID-19. If state parties wanted DNC funding, they had to follow the rule. Hinojosa said he pushed back on that requirement, knowing how important personal contact was to turning out voters, especially in the close-knit communities of South Texas. “Joe Biden made a decision that we were going to be the responsible party, unlike the Republicans, who were doing in-person campaigning,” he said. “So we were campaigning with one hand tied behind our back.”

Biden’s criticism of the fossil-fuel industry, which powers the Texas economy, also didn’t help, Hinojosa said. Neither did the anti-police backlash after the murder of George Floyd, particularly in South Texas. “There are something like 20,000 Border Patrol agents in the Rio Grande Valley,” Hinojosa noted. “They’ve married into the Valley, they have family members in the Valley, they have friends. So when you start talking about defunding the police, people freaked out.”

For decades, Democrats thought they had one big structural advantage in the state. The Hispanic population is booming, while the percentage of non-Hispanic white Texans is falling. Texas Democrats have long seen that demographic trend as spelling the inevitable end of Republican rule—especially given the GOP’s increasingly radical anti-immigrant rhetoric. But Trump’s unexpectedly strong showing in South Texas in 2020 forced at least some Democrats to question this comforting belief. “When a [non-Hispanic] white liberal activist thinks about South Texas, they see people of color; they don’t see swing voters,” said veteran Democratic strategist Jason Stanford. “It’s been really hard to convince the donor class, which is overwhelmingly white, that South Texas needed investment. They one hundred percent take it for granted. They always have.”

The 2020 election also called into question Democrats’ favorite mantra: that Texas isn’t a Republican state, it’s a low-turnout state. In 2020, Texans, including Hispanics, came out in record numbers—they just didn’t vote for Democrats. “There has often been a belief in the Democratic Party that demographics are destiny,” said Cristina Tzintzún Ramirez, a labor organizer and former Democratic senatorial candidate. “But then they fail to invest in those demographics. There was not enough time, focus, or money spent on the Latino vote.”

Many of the Democratic officials and operatives I interviewed said Hinojosa is doing as well as possible given what he’s up against: a well-funded, deeply entrenched Republican party that has dominated Texas since the early nineties. Gerrymandered maps give Republicans a structural advantage, while voter-suppression laws, such as the one passed last year that state House Democrats initially broke quorum to deny, disproportionately affect urban and minority voters, who tend to vote Democratic. Because of Texas’s size and multiple large media markets, it’s always been extraordinarily expensive to run statewide political campaigns here—another structural disadvantage for a party with limited resources. “A lot of the time we blame losses on the state party,” Stanford told me, “which is about as dumb as blaming whether Hillary or Bernie won on the Democratic National Committee. The party’s only real function is to hold elections and build infrastructure.”

The problem, as Olson and Robinson see it, is that in much of Texas the Democratic party has no infrastructure. “You ask any rural county chair out there—no one visits them,” Olson told me. “The party does little to help them. The idea is, that population is red and they’re always going to vote red. And I think that’s a mistake.” Robinson told me that he’s been traveling the state for months, meeting local Democratic candidates who have no connection to the state party in Austin. “There are Democratic nominees who were nominated in March that have never been talked to by the Texas Democratic Party,” he said, incredulously. “I cannot express to you my level of frustration that we don’t even reach out to our candidates.”

The conventional wisdom in the party—and part of Hinojosa’s strategy to turn out more liberal voters rather than winning back conservative ones—has long been to focus on the state’s booming urban areas and the fast-growing population of the Valley. But by ignoring rural counties, Olson and Robinson say, the party is effectively surrendering much of the state to the Republican party. Even a small Democratic shift in the rural vote might well have handed Beto O’Rourke the 2018 Senate seat, which he lost by fewer than three percentage points. To his credit, O’Rourke campaigned vigorously in rural counties—and with a centrist message. But with virtually no party footprint in much of the state, there was nobody to turn out the vote for O’Rourke on Election Day.

The issue, some Democrats say, is that when party leaders look at rural Texas they see nothing but non-Hispanic whites whom they presume will vote only for Republicans. “When you listen to the state party talk, it’s as if there are no people of color outside of the big cities,” said one Texas Democratic activist, who asked to remain anonymous in order to speak candidly. “When you look at some of the close margins we’ve had, they can be made up in the cities, but they can really be made up in the rural parts of the state as well.”

In Hinojosa’s view, the decision to neglect rural areas comes down to funding. “It’s easy to say, well, we should have put more money into rural counties. But when you’re working with limited resources, you have to put it where you’re going to get the most bang for your buck.” But this familiar complaint rings hollow when you consider that Texas Democrats raised and spent a record $200 million in the 2020 campaign. Do Democrats suffer from a lack of money? Or from a fundamentally flawed strategy?

The race for state party chair has been unusually combative—and personal. In December, Olson called Hinojosa misogynistic for referring to her as “this woman” in an interview. Hinojosa apologized for not being more careful with his language, then turned around and accused Olson of physically assaulting a staffer during her 2018 campaign for agriculture commissioner. He said that at an event in Killeen honoring veterans, Olson had become upset that she, as a veteran, was not seated more prominently. When Crystal Perkins, then the executive director of the state party, attempted to address the dispute, Olson allegedly shoved her, causing Perkins to fall backward. Perkins has confirmed that version of events to reporters, but Olson told me it never happened. “All I did was use my colonel voice,” she told me.

Whatever happened, there is clearly no love lost between Hinojosa and his two opponents. In his interview with Texas Monthly, Hinojosa all but accused Robinson and Olson of buying off party officials to win their support. “They are running around to all these county chairs, saying they’re going to give them grants from the Texas Democratic Party if they get elected,” he said. “They don’t say where they’re going to get the money. Neither one of these individuals has any history of raising large amounts of money. None.”

Olson appears to have the best chance of beating Hinojosa. She launched her campaign in December and has been endorsed by sixty county chairs, as well as hundreds of former Democratic candidates, donors, and activists. Among her supporters is Chris Rosenberg, the chair of the Bell County Democrats and president of the Texas Democratic County Chairs Association. Rosenberg said that “our failures to win statewide races are costing people’s lives”—a reference to the Uvalde massacre, which he believes could have been prevented by stronger gun regulations, as well as to Republican positions on abortion access, health care, and LGBTQ rights. “I think we have been lacking a message that resonates with Texas voters. And we don’t seem to have a viable strategy.”

Hinojosa will celebrate his seventieth birthday on July 8, less than a week before the state Democratic convention kicks off in Dallas. He told me that if he wins reelection, it will be his final four-year term as chair. “I’ve given ten years,” he said. “This is hard. I spend so much time traveling the state, staying at hotels, going from one event to another, one meeting to another. I’m on the phone every day, hours at a time. But I’m going to give it one last time. We have to flip the state.”

Correction: The original version of this story said Mayra Flores was the first Republican to represent part of the Rio Grande Valley since Reconstruction. Republican Blake Farenthold represented a district which included a slice of the RGV from 2011-2013.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Beto O'Rourke