Sometimes his phone would ring smack in the middle of dinner, while the pasta and sausage were still steaming on his plate. Sometimes it would ring at ten p.m., midnight, two in the morning. On the other end of the phone was a detective, and the conversation would go something like this: “Richard, you’ll want to get here real quick because this one’s a mess. See you soon?” The answer was yes, always yes. He’d shoulder his camera bag, head out the door, and ready himself for the dark hours ahead. Coffee? He’d grab a cup near the murder scene.

While embedding with the Dallas Police Department’s homicide unit for nearly a year, Richard Sharum photographed the aftermath of some sixty murders. That doesn’t count the scenes of accidental deaths, of suicides, of overdoses; there were more than a hundred of those. He saw miles, literally miles, of yellow police tape, as well as chalk outlines in every conceivable shape, depicting the pretzel positions in which lives ended. He came to know the detectives—Curtis, Criddle, Chaney, Grubbs, Kramer, Rojas, Sayers, Valdez, Wheeler, and the rest—like family. At the scenes, which took him to homes in the rougher corners of Dallas but also underneath highway overpasses and inside tranquil churches, Sharum saw people who had been murdered while lying in their beds or sitting on their sofas, who had been bludgeoned, burned, hog-tied, dismembered, stabbed, suffocated, or shot. Mostly shot.

Sometimes he arrived ahead of the detectives. His access allowed him to wander through the most gruesome crime scenes but also join the detectives at Sunday dinners with their families. In a sense, his mission was straightforward: find a way underneath the formulaic depictions of homicide that many Americans watch on TV before padding off to bed or listen to on a podcast while heading home from yoga class. He was committed to pricking at our growing numbness around this violence, to showing us the reality of something we think we understand but do not.

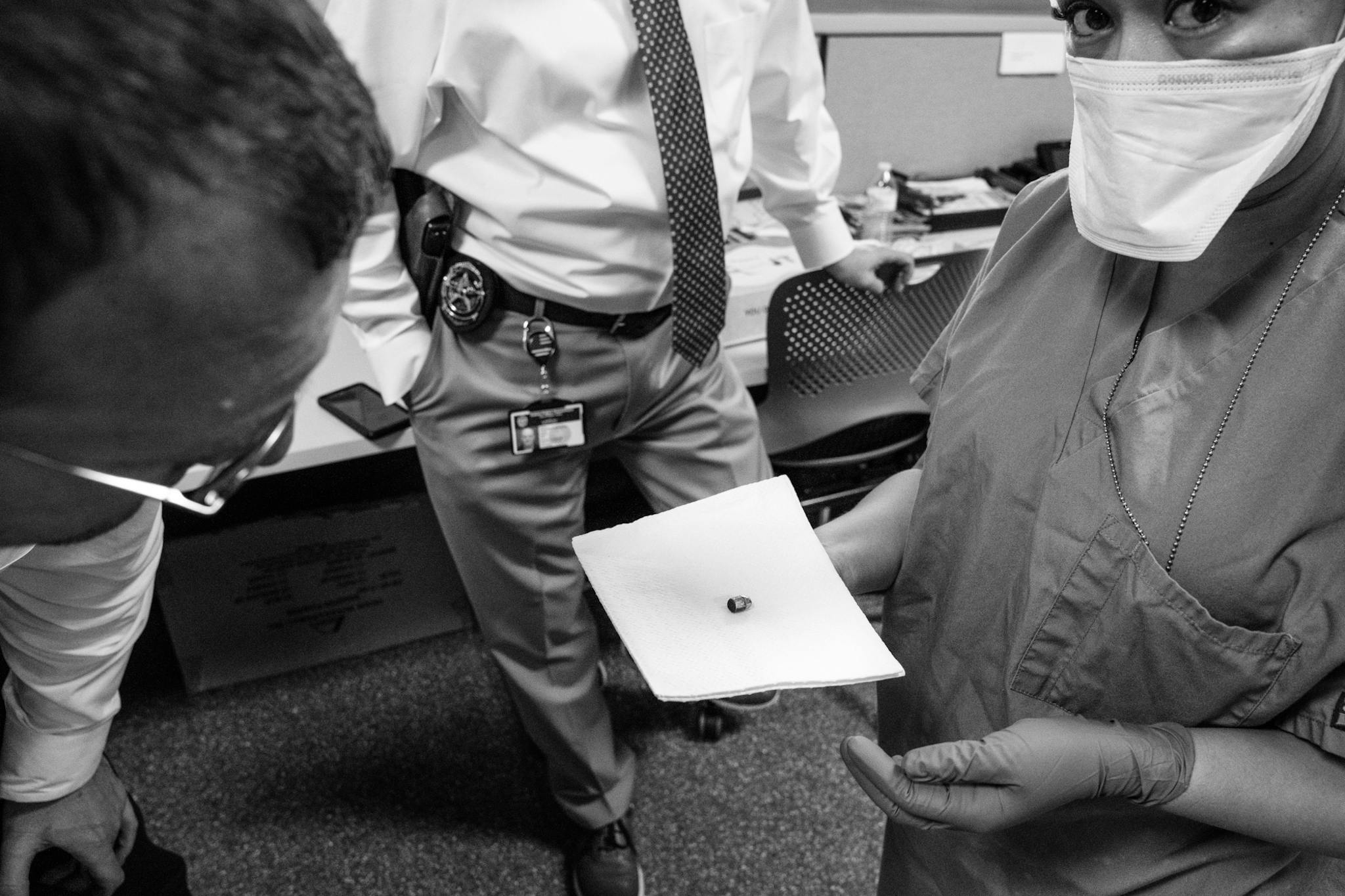

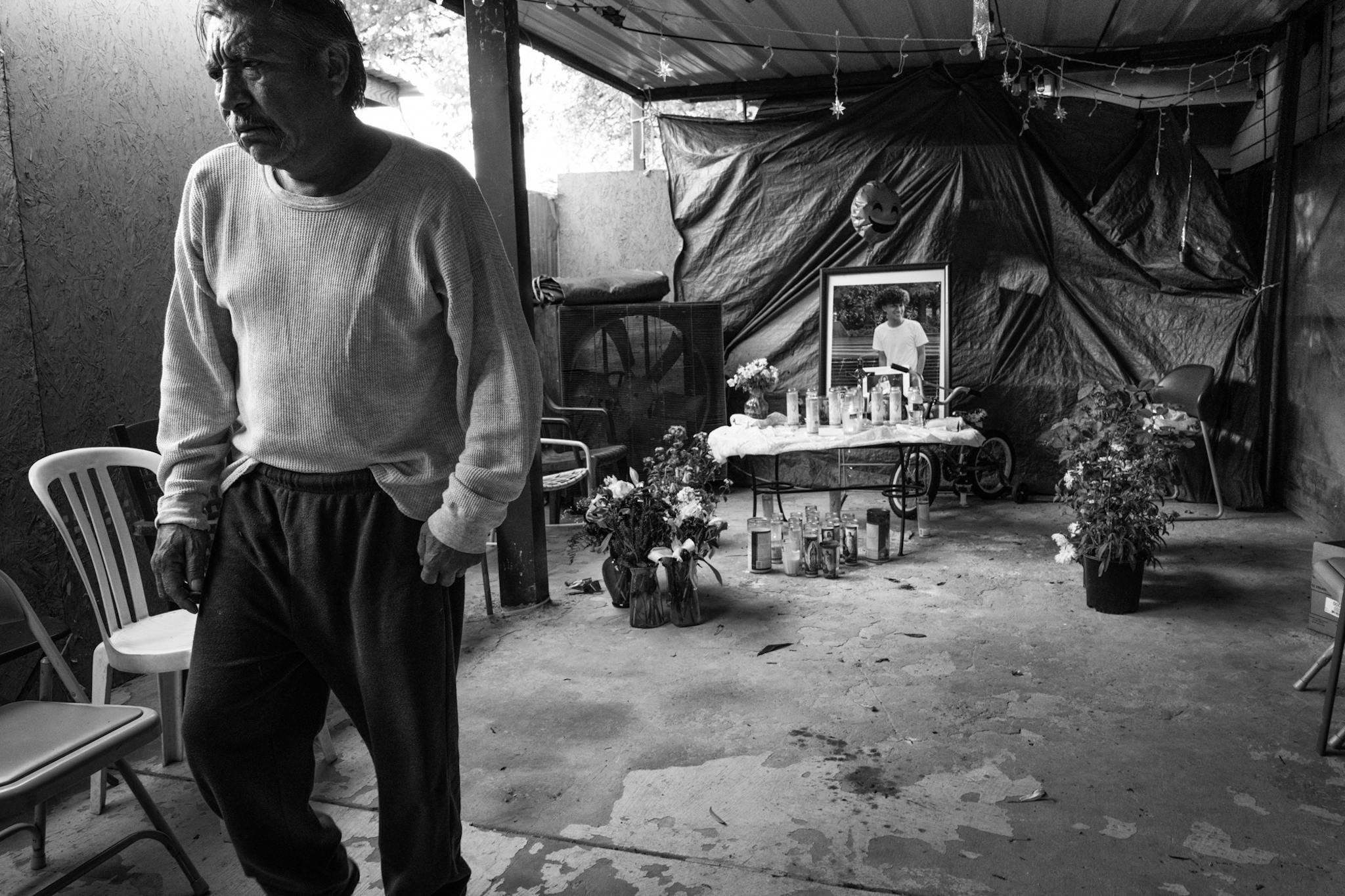

Sharum saw things he will never be able to shake: the two-inch hole knifed into a man’s throat while he sat in his white utility van. The nine-year-old boy shot in the back as he slept in his pajamas, a victim of his mother’s ex. The dead man whose hands stiffened in a begging posture and the surreal practice of bagging victims’ hands to preserve evidence. He photographed it all, recording even those aspects that were difficult to capture in the click of his camera’s shutter, such as the quiet devastation that descends on a murder victim’s family. Such as the absence of a person.

Sharum found that same deep valley of loss in a place where most don’t bother looking: among the families of those who committed murder. The guilt and anguish the perpetrator’s family experiences is seldom shown on reruns of Law & Order. We rarely see that when a murderer is sent away to prison, a father or son, a mother or daughter, is suddenly missing from the home, and that their relatives often become pariahs in their community overnight—unwelcome at church, school, the supermarket, even an old friend’s front porch. In the United States, Sharum discovered, some 150 support groups are specifically designed to help families of murder victims. For the families of killers? There appear to be zero.

Dallas was one of just a few major U.S. cities where murders increased in 2023-—up to 246, according to the police department, compared with 214 the previous year. That’s an especially troubling number when you consider that a single homicide touches a vast ecosystem: beat cops, ambulance drivers, fingerprint techs, police photographers, the “body snatchers” whose job is to ferry the dead to the medical examiner’s office, coroners, undertakers, lawyers, witnesses, jurors, judges, court staff, prison guards, therapists, and, of course, families and friends of both victim and perpetrator. One murder can easily touch three hundred people, a number that doesn’t begin to account for the thousands who will read about it in the paper, see it on the news.

The detectives, of course, are a key part of this landscape, and their lives get swept up in the storm that each body brings. But not, Sharum learned, in the way the cop shows often portray. The Dallas detectives do not close down the local bar in a haze of beer and Tito’s. They do not keep worn photos in their wallets of the wife who left them. They are skilled in the art of compartmentalization. They go home to their families. They sit down to tacos at dinner. They ride horses with their kids, collect antique spurs, coach Little League, go to church.

They seldom talk with civilians about their work. At backyard barbecues, friends ask them about this case or that, looking for lurid details. But the detectives know from experience that the backyarders don’t want to know the truth. Even among their spouses, the rule is don’t ask, don’t tell. Detectives talk homicide only with other detectives. It’s a bubble, but not one meant to protect themselves; it’s to protect those on the outside.

Sharum experienced this too. A Dallas homicide detective spends one week on call—meaning that if a body turns up, the detective dashes to the site, day or night—and then works the next three weeks tracking down witnesses, conducting interviews, filing paperwork. Sharum put himself on call for months at a time, seeing body after body, distraught family after distraught family. It began to feel like a nightmarish conveyor belt.

He found himself existing in a kind of parallel universe. Whenever he’d dip into a convenience store to grab a water, he’d see customers picking out chips or an energy bar, but at the same time he’d imagine them from the viewpoint of the store’s surveillance cameras because, standing alongside the detectives, he’d viewed hours of footage depicting the moments just before a gun was drawn and a body fell. In the past, he might have driven by a jogger and thought, Man, I gotta start running again. Now the voice in his head would say, This person has no idea what world we live in.

It wasn’t the gore and chaos that pierced Sharum most deeply. It wasn’t the corpses sprawled on the street, which he somehow got used to. What haunted him the most were the bodies he observed in their homes, collapsed there in the doorway, maybe sagging awkwardly on the sofa. Signs of a life would be everywhere: keys on the counter, coffee mug on the kitchen table, signed photo of Tony Dorsett tacked to the wall, dog ambling through the house. The victim clearly had no idea it was the last time he’d plunk those keys on the counter, set down that coffee.

At one murder scene, in a drug dealer’s house, a man had been shot twice while sitting on his couch. To Sharum it seemed as if the victim had been asleep and woke only when the gun went off. There were cardboard signs on the walls (the man’s Venmo handle for the drug buyers), dishes in the sink. Sharum noticed the record player with Bill Withers’s Still Bill on the platter and realized he owned the same album—and that it was likely the last music the dead man had listened to. Sharum glanced over at the fridge and saw drawings crayoned by kids who were perhaps a little younger than his. Everything felt relatable. Everything at scenes like these made him wonder where and how he would draw his own last breath.

Yet even as he witnessed so much death, even as he wondered about the victims’ final moments, Sharum also found himself focusing on their lives up to the point when the gun went off. He could almost see the images of their days—when they were two years old toddling around the kitchen, then five and laughing in the front yard with friends, having their school photo taken for the first time, a first kiss, the birth of their child—appearing before him as if in a family photo album, an album whose last pages had gone missing.

There was only one time that the phone rang and Sharum said no, he wouldn’t meet the detectives at the murder scene. That call came just as he was sitting down to dinner, the day after his time with the detectives had officially finished, after he’d said his goodbyes. For nearly a year he’d lived the life of a detective, and now he was done. Sharum answered his cell, and Detective Patty Belew explained there had been a quadruple murder—a rare occurrence and something Sharum hadn’t seen before—and encouraged him to come to the scene. Sharum demurred, saying he was eating with his family and that his assignment was done.

But to Sharum’s surprise, his wife urged him to go. It’s just one more night. They could have a family dinner tomorrow. So he shouldered his camera bag, plucked his keys from the counter, and headed for the door.

A couple of hours after Sharum arrived at the scene, a two-story apartment complex in northwest Dallas, he learned that Detective Guy Curtis, a 21-year veteran, had spotted the suspect’s black Mustang. It was parked just a couple of miles away, and Curtis was quietly keeping an eye on it. A sergeant looked Sharum in the eye and told him not to go, that it was too dangerous. Sharum nodded . . . then sneaked into a car with Detective Scott Sayers.

It was around 10:30 p.m. when they pulled up next to Curtis. While the detectives, waiting in unmarked white Ford Fusions, their headlights dark, whispered to each other through open windows, Sharum noticed a young couple with a baby walking maybe ten feet away. He noted the name on the back of the man’s varsity-style jacket—the same name he’d heard the lead detective mention while on the phone back at the crime scene. The couple was maybe fifty feet from the Mustang when Sharum tapped Sayers on the shoulder: “That’s him.”

Then everything happened fast.

Just before the suspect reached the Mustang, the detectives simultaneously hit their headlights, stomped on the gas, and rushed him. Curtis jumped out of his car, racked his shotgun, and leveled it directly at the suspect, yelling, “Police! On the ground!”

Sharum leaped out of the car too. Once again he pointed his camera into the chaos.

Richard Sharum’s book, American Homicide, will be published in 2025 by Gost Books. Bill Shapiro is the former editor in chief of Life magazine.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “To Live and Die in Dallas.” Subscribe today.