This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On any weekend this fall, a traveler driving the disciplined, palm-lined grid that carves up the Rio Grande Valley might be forgiven for wondering whether he had happened upon some obscure local holiday. Across Cameron and Hidalgo counties, the scene repeats itself in city after city, town after town, hamlet after hamlet. First you glimpse a motley herd of cars converged on a vacant lot or field. You catch the sharp perfume of mesquite smoke before you see it chuffing up from oil-drum barbecue grills; the chipper bip-bip-bip of norteño polkas filters toward the highway. From blocks away, you can make out a crowd eddying among billows of red, white, and blue in a composition Brueghel might have savored. A street fair maybe? A festival that the Texas highway department forgot to publicize? No, it’s just election season in the Valley, and the pachanga circuit is in full swing.

Baldly translated, “pachanga” means “party.” But freely rendered with all its nuances, it signifies something highly specific—a combination beer bust, barbecue, and political rally. Let urban Democrats and Republicans stage wine-and-cheese receptions in rented hotel meeting rooms; South Texans are heir to a juicier campaign form with conventions all its own. Vital elements of a proper pachanga are a free Mexican-style barbecue dinner and keg beer. An outdoor setting, preferably shaded, is optimal, live conjunto music is highly desirable, and the male dress code dictates casual wear in the guayabera mode. It’s customary for the candidates who are being honored to give short speeches, and the obligatory flesh-pressing includes a healthy helping of abrazos, those ritual bear hugs of South Texas men.

The high holy season for pachangas is spring, simply because the Valley is so thoroughly Democratic that at a local level the primaries are still the only elections that matter (88 per cent of the voters chose the Democratic ballot in the 1986 primaries). Fall pachangas are another animal, more in the nature of Democratic pep rallies resounding with cries of “Una palanca!” (“Pull the single lever!”) The pachanga derives from the same rural, down-to-earth impulses that shaped the East Texas political fish fry, but its style combines elements of Mexican and Anglo cultures in a way peculiar to the border region. The pachanga is the most obvious political illustration of the way the two cultures merge in this separate land, isolated from the rest of the state by miles of sparse and silent brush.

Here Comes the Judge

It is one of those delicious cross-cultural paradoxes that few South Texas politicians are more adept at working the frenetic pachanga circuit than an Anglo, state district judge Joe B. Evins of Edinburg. A diminutive, avuncular, crinkly-eyed man with gray hair set off by a permanent Valley tan, Evins won a large measure of popularity and respect during his thirteen years on the bench. He has turned into a political dinosaur in Hidalgo County; he is the last Anglo to hold office on a county wide level. Over the last decade Anglos, accustomed to being thrashed by Mexican American candidates in all but the most localized contests, have pretty much given up running. And this spring Evins, who usually runs unopposed, drew a challenger with a Hispanic surname—Israel Ramon, Jr., a young Edinburg lawyer. As the first hot Anglo-versus-Hispanic race in recent memory in Hidalgo County, it was the subject of intense speculation. The question in everyone’s mind was whether ethnicity would be a decisive factor, whether Hispanic voters would opt for the relatively untried, little-known, and underfunded Israel Ramon merely on the basis of his name. Nobody claimed to know the answer, but Evins was campaigning as if his life depended on it.

Evins’ final preelection weekend in April showed him as the masterful South Texas campaigner he has become, more Hispanic than Anglo in his style. After a four-hour Saturday evening blitz of five pachangas and a wedding, he kicked off Sunday at a pachanga tossed for him by the McAllen Firefighters Association. Outside State Representative Juan Hinojosa’s low-slung North McAllen law office at high noon, firemen sweated over fajitas on big trailer grills while screeching buzz saws bit into mesquite logs and Los Originales warmed up under the hackberry trees. Evins had gone pure South Texas for the day in black guayabera, black slacks, and sunglasses. There’s an element of cross-cultural calculation in how a candidate dresses for a pachanga: some go the man-of-the-people route, making a statement in shirt sleeves; others conspicuously dress for success in suits, casting themselves as public figures. A canny few, like Hector Uribe, the Brownsville state senator cut in the polished, mediagenic Henry Cisneros mold, strike a bargain by doffing their suit jackets and rolling up their dress-shirt sleeves.

While Evins dispensed easy, bilingual pleasantries with early arrivals, his political antennae moved ceaselessly. He compared pachanga data with other candidates, rearranged his schedule on the spot, grilled me about rival pachangas set for later in Elsa and Edcouch, and summoned an aide to find out what was going on over at an address on South Twenty-third Street. Evins can’t bear to miss anything. “He’s one of the very few Anglos who will attend every single pachanga, even in the barrio,” says Juan Hinojosa.

By one o’clock a mostly middle-class Mexican American crowd of about fifty had straggled in. “There are so many competing pachangas today that people aren’t lined up for food by the hundreds the way they’d be in March,” rationalized Mike Sinder, Evins’ lieutenant.

The judge was restless. “I’m gonna run over to El Bingo Grande and get back here at two,” he muttered to Sinder, taking off with a group for the hangar-size bingo hall in nearby Pharr.

El Bingo Grande was a maelstrom of about two thousand people and an electrified grupo exploding with colored smoke and bombing-raid sound effects, a shock after the low-key, family-picnic atmosphere of the firefighters’ pachanga. A line of perhaps four hundred people jostled to acquire plates of carne guisada, chicken, and salsa. Couples syncopated on the dance floor, and innumerable kids raced down long aisles of bingo tables littered with white avalanches of campaign material. In its giant scale, its indoor urban setting, and its family orientation, the pachanga screamed 1986 —it resembled a manic political convention rather than a rustic barbecue. Judge Evins moved smoothly through the melee, joshing now in Spanish, now in English, and paying his respects to cosponsors J. Edgar Ruiz, a candidate for county judge, and Joe Vera, a vast mountain of a man making a dark-horse challenge to the incumbent Democratic county chairman.

Vera had wrought this circuslike pachanga in his own P. T. Barnum-of-the-Valley image. He had been touting this bash on his radio hour for weeks, and the publicity had paid off with a crowd that was a candidate’s paradise. Not all the guests would vote for both Vera and Ruiz, of course, nor could the event be read to mean that the heavily favored Ruiz and the long-shot Vera were supporting each other. The pachanga circuit brings together some strange political bedfellows; the increasing size and complexity of such affairs dictate that cosponsorship deals be struck, with considerations of who can bring what to the table—be it food, music, a hall, organizers—as well as of who is endorsing whom. Even the folks miffed at the temporary Ruiz-Vera alliance recognized it for what it was: pragmatic.

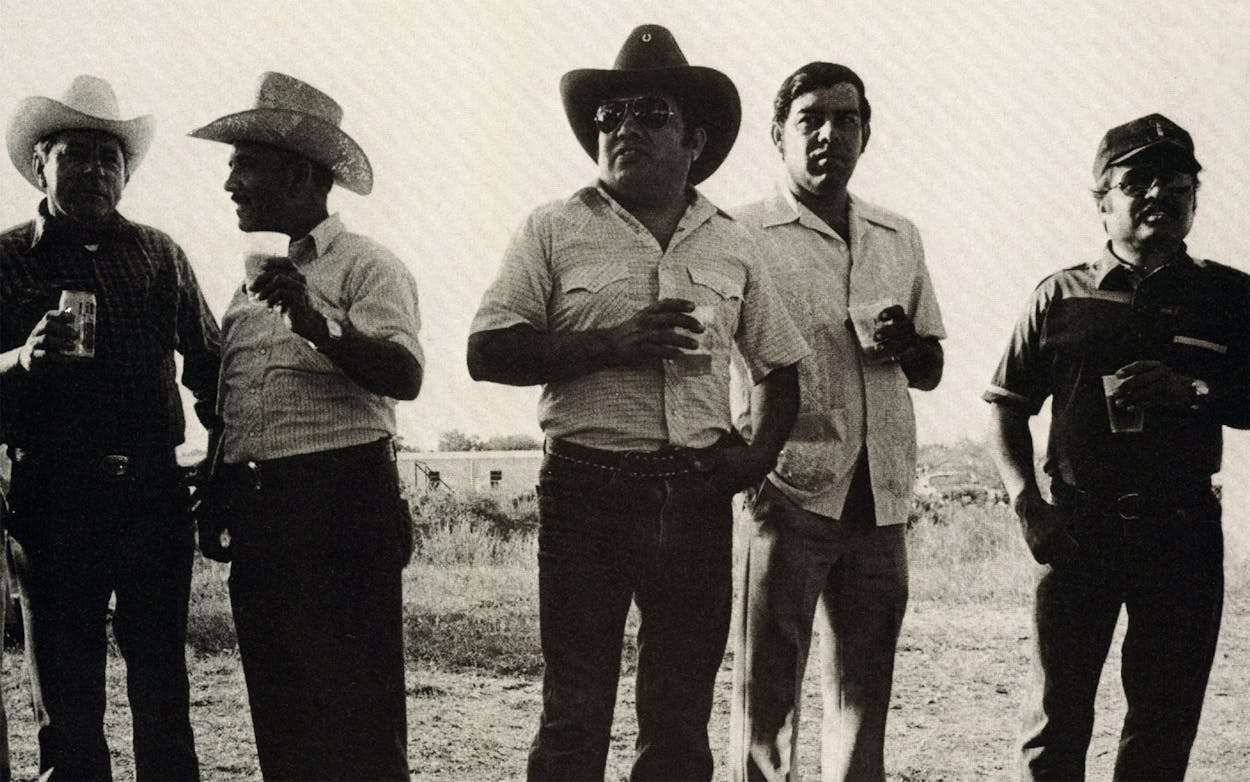

Having milked El Bingo Grande for all it was worth, Evins stopped by his own pachanga long enough to schmooze and partake of the firemen’s fajitas and a glorious mess of soupy pintos laced with salt pork and cilantro. Then it was on to the town hall at Alton, a small crossroads village northwest of McAllen, for a grassroots pachanga that was like a step back in Valley time. The crowd had segregated itself by sex. While the townswomen perched on lawn chairs brought from home, the khaki-clad men banded around the edge of a parched gravel parking lot, lounging against pickup tailgates or posing in typical pachanga stance—arms folded, feet squarely apart, faces inscrutable under straw hats and sunglasses. A small knot of men lingered at the beer keg, some less steadily than others (pachanga etiquette seems to decree that women may be brought beers, but they should not infringe on the male preserve of the keg). A band played; the Valley winds flailed the tall stands of skinny sunflowers that spread away on every side.

Inside the spare, white-clapboard hall, female volunteers dished out a modest meal of carne guisada while Sanjuanita Zamora, the redheaded mayora, greeted guests with county commissioner Beto Salinas, the power broker who had ramrodded this and five other pachangas on behalf of his handpicked slate of candidates. As Evins entered the hall, the mayora pressed him to eat; he deftly dodged the issue. Then it was outside for the speeches, all of them in Spanish, no translations here. Evins was suddenly transformed: gesturing as expressively as any Hispanic, speaking in serviceable if choppy Spanish, complimenting the city fathers and mothers effusively, and bringing forward his beaming wife for perusal. “Mr esposa . . . come here, Mama . . . cuarenta anos pasado” (“married for forty years”). The crowd ate it up, applauding furiously. In an instant you could see why Evins is a special case. He’s the bicultural good ol’ boy.

Then it was back into their cars for Evins and his small entourage, driving west to the almost totally Hispanic area called the Delta. Two justice-of-the-peace opponents were staging dueling pachangas in the adjacent burgs of Elsa and Edcouch, a symbolic nose-thumbing. In one corner, feeding more than nine hundred people in a field alongside the Elsa railroad tracks, was Apolonio Gutierrez, a twinkly sixteen-year incumbent. In the other corner, feeding maybe six hundred folks in a field off Edcouch’s main drag, was mustachioed Ruben Rodriguez, an ambitious young Texas Department of Agriculture inspector who wanted Gutierrez’s job.

The Delta is a part of Hidalgo County where an unfamiliar gringo is a stared-at curiosity, but Evins was in his element, as usual. He took the mike at a little cement-floored bandstand and interrupted the juky, old-timey dancing to say what an honor it was to be at Apolonio Gutierrez’s pachanga. Many of the gritty, plainly dressed crowd looked as if they could use the mesquite-barbecued meal that Gutierrez’s troops had put together with quartered chickens, at 37 cents a pound, and assorted donations. One weary-looking father, trailed by his daughter and two small sons, trudged away from the littered grounds bearing napkin-wrapped plates back home. Espiridion “Speedy” Jackson, a sweet-natured fellow in cowboy clothes who is mayor of next-door Edcouch, waxed philosophical at the scene. “Thank God for politics,” he said fervently. “If you didn’t have politics here in the Valley, what else would we do?”

Joe Evins was already in his car and on his way to Edcouch. There he nimbly touched base with Ruben Rodriguez, got himself introduced from a tractor trailer where a brassily electrified conjunto blared away, and announced what an honor it was to be at Ruben Rodriguez’s pachanga. The speech played as well in Edcouch as it had in Elsa. By now the light was failing, but the oil drums kept smoking, and the food line was going strong. People had donated the fryers and the beer, Rodriguez explained, surveying the workclothes crowd that clogged the lot. “This is supposed to be the poor party,” he said with a wry arch of his eyebrow, clearly pleased at the way it had turned out. “I just don’t have the money Gutierrez has got.” And in the end, Rodriguez had about five hundred fewer votes than Gutierrez had, too. Meanwhile, Evins, whupping Israel Ramon by almost nine thousand votes, went on to prove that the right kind of Anglo can still win big in the Valley.

From Patron to Pachanga

South of the Rio Grande to Tierra del Fuego six thousand miles distant, the democratic tradition runs as shallow and sluggish as the river itself. For most of its history, South Texas lived under a political system that had more in common with Latin America than the United States. The region was run by patrones, large landowners who were in effect feudal lords with Mexican laborers as serfs. On election day the workers were brought into town and told whom to vote for; they found their rides home by looking for colored ribbons tied to their means of transportation. Over the years trucks replaced wagons as a way of getting voters to the polls, but otherwise the system remained unchanged for generations.

The pachanga circuit was born of the patron system. In the days of big ranches, pachangas were exclusive affairs. The men who made the decisions congregated, often on horseback, from all corners of a county. They anointed their candidates, ate barbecue, and dispersed. But the Voting Rights Act, the one-man-one-vote principle, and the eventual awakening of Mexican American political ambitions finally scuttled the patron system. The seventies saw the emergence of South Texas’ hybrid politics, which adapted Anglo-Saxon political institutions to an area with an 80 per cent Hispanic populace. The freshly empowered Mexican American voters, once stereotyped for their indifference to politics, emerged zestfully engaged in the push and pull of the political arena and newly enamored of the franchise. Today the Valley records primary turnouts of up to 30 per cent, putting other Texas metropolitan areas to shame.

South Texas subtleties are often lost on the Texas politicians who, more and more, are making the Valley a must stop on their campaign itineraries. Rare is the outside pol who grasps the principles at work under the strong Valley sun and the stiff winds that barge in relentlessly from the Gulf. In an era of polls, phone banks, television, and computerized direct mail, the Valley remains an outpost of a style in which personal contact and relationships are crucial and in which the worst accusation you can make about a candidate is not that he used a cattle prod on his mistress or pleaded insanity after soliciting the murder of his lover’s spouse (two of the more lurid charges in Hidalgo County’s May primary) but that he lost touch with his constituents. That is the ultimate sin.

Along with huge public dances known as bailes, the pachanga circuit is one of a Valley candidate’s foremost means of cultivating the all-important personal connections. Conventional wisdom dictates that you don’t actually win votes at a pachanga but you can lose votes by not showing up. “You’ll make your supporters angry. What people want is to be able to tell their friends, ‘Judge Evins was here yesterday, he shook my hand, he remembered me. He cared enough to be here,’ ” says Sinder, who handles political advertising for Evins. “It’s the talk they do about it later that helps you.” State Representative Alex Moreno of Edinburg agrees. “There really are differences between Anglos and Hispanics,” he says. “People talk in symbols here. We rely a lot more on feelings. People here want to shake your hand, look you in the eye, and see if you’re sincere about the symbols.”

Another thing many Valley voters require is to eat and drink with their candidates, acts that amount to a political sacrament. Your basic pachanga-goer won’t take no for an answer. State Representative Rene Oliveira of Brownsville, who lost his May primary in an upset, calls the pachanga season “the fifty-pound circuit” and moans, “I never want to see another piece of barbecued chicken or fajitas.” Survival techniques are critical during the height of the season, when a truly determined candidate may hit more than six pachangas a day. “People get offended if you don’t drink with them,” says McAllen legislator Juan Hinojosa, “so you quickly learn to nurse a beer through a whole pachanga.”

The democratic-with-a-little-D nature of pachangas produced a political etiquette that is at odds with the protocol for gatherings in the rest of the state. It would be unthinkable for, say, Phil Gramm to show up uninvited at a function for Bill Clements. In keeping with the freewheeling character of pachangas, however, the gatherings are open to candidates other than honorees. The pachanga code was vividly demonstrated one balmy Saturday evening last April outside the comfortable, Spanish-style North McAllen home of Richard Salinas, an engineer, politico, and pachanga-giver of note. Traffic snarled for blocks as more than three hundred people crowded into a long yard shaded by feathery hackberry trees and arranged with rented tables and filigreed garden benches. Palms rattled in the insistent breeze, and Mariachi Continental struck up with a brassy flourish.

Holding court near a trio of campfires was Salinas in a powder-blue jumpsuit and a Bud Light gimme cap. Shirt-sleeved men in their best Western boots clustered around the beer keg; Salinas’ wife, Alida, superintended a serving line that dispensed cabrito, guisado, rice, and beans. Passersby slowed their cars to gawk at the spectacle, drawn by the noise, the throng, the boxcar-size campaign signs mounted on truck beds along the street.

Unlike grass-roots pachangas that are open to the public (many are splashily advertised in the newspapers as “Free Bar-b-ques!”), the Salinas do was a more selective affair organized through verbal invitation and the hyperactive political grapevine. The pachanga honored Salinas’ two favored candidates, Hidalgo County clerk J. Edgar Ruiz, who was running for the powerful county judge slot, and La Joya mayor Billy Leo, who wanted to move up into Ruiz’s current post. Perhaps two thirds of the candidates on the county ballot came to work the crowd and take advantage of the turnout. “There are people here I endorse and people I don’t,” Salinas explained, eyeing the circulating candidates, “but I feel obligated to let them mingle.” What if the opponents of the honorees appeared? “I’d greet them and shake their hands,” he said with a shrug. But the message is clear: they know to stay away. According to protocol, only Ruiz and Leo would be allowed to address the crowd; the more informal and rural the pachanga, the greater the likelihood that any candidate who showed up would be invited to say a few words.

Salinas’ back yard made a primo pachanga site. It was smack on a major north-south thoroughfare and visible from the street—just the ticket for an impressive show of strength. “The whole idea is for a pachanga to create a lot of talk,” said Salinas. “For the next three or four days, people will be saying there was such a traffic jam the cops had to break it up.”

You Are What You Cook

Few comers, least of all the fiercely proud proprietors, are indifferent to the meal that is the cornerstone of every pachanga. Pachanga fare is painstakingly, personally wrought by the party’s sponsors; to leave it to a disinterested caterer would be unthinkable. The conviction that things must be done correctly is what sends a pachanga host like Richard Salinas off to the stockyards to pick out just the right calf for a veal guisado, gets him to enlist a butcher pal to slaughter a dozen goats for the cabrito, and compels him to round up buddies and political cronies (and every beat-up black iron kettle at their disposal) to do the cooking honors.

A certain machismo often governs the barbecuing. Everything at the Salinas pachanga was nursed over the campfires by the guys, save for a complex, classy salsa whipped up by Alida Salinas and doled out by the womenfolk from lettuce-lined molcajetes. The masculine aura is as old as the pachanga tradition. In the past a woman’s pachanga function was to cook and serve and keep out of the way. The food was apt to be primal rancho grub like whole barbecued pig and pan de campo, the sturdy South Texas skillet bread.

Rare is the pachanga at which anyone goes to the trouble to cook an entire pig anymore, and in many quarters of the Valley the dread gringo white bread has supplanted pan de campo and tortillas. The pachangas of the eighties break down into two basic food categories: chicken and beef. Chicken has emerged as the answer to a financially pressed pachanga-thrower’s prayer. Barbecued over mesquite, it’s a staple at affairs held in rural colonias or urban barrios, where a come-one, come-all ethic dictates maximum food at minimum cost and where the number of free dinners served is a populist’s dream. Chicken is likewise a godsend for candidates who throw their own pachangas as fundraisers and sell tickets for a nominal fee—another modern wrinkle.

What chicken is to a money-conscious pachanga, beef is to an elite pachanga. And no, “elite pachanga” is not a contradiction in terms. Outsiders tend to lump all Valley politics together, little realizing that class divisions are as important here as anywhere else. While some pachangas cut across class lines, others are identifiably poor or middle class or rich. And uptown pachangas demand beef, whether it be fajitas, barbecued brisket, or the kind of calf guisado cooked up by Salinas and his friends.

The most sumptuous beef of the season may have been served at a rarefied, invitation-only party thrown by Harlingen lawyer and banker Rollie Koppel at his weekend farm retreat. Koppel, an amused-looking man, received his guests, wearing a bolo tie and denims so elegantly bleached out that Ralph Lauren would covet them. Tethered beneath palm trees stood a saddled horse, the perfect nostalgic prop for an event that underlined the Valley’s thoroughly hybridized culture—a pachanga given by an Anglo for an Anglo.

Koppel’s guest of honor was State Senator Oscar Mauzy, a candidate for the Texas Supreme Court and a man sorely in need of a pachanga to mend his South Texas fences. A lot of Valley politicos were mad about the campaign leaflet that Mauzy and fellow court candidate Jay Gibson had released. Only one small thing was wrong: West Texan Gibson was running against Valley native Raul Gonzalez, the incumbent. When Gonzalez showed up at Koppel’s farm, the guests—a mostly male group of contented-looking burghers and pols—watched from the corners of their eyes to see what would happen. Fortunately, the civilities of pachanga etiquette prevailed.

Inside a screened white pavilion, three young Raymondville politicos, impeccable in custom boots and starchy Western shirts, dug into the museum-quality beef ribs and brisket that had been coddled all day by Oscar Correa, vice president of Koppel’s Raymondville Bank. Now this, agreed Raymondville mayor Joe Alexander and school board trustees Frank Gonzales and Arturo Garza, was what pachanga connoisseurs held out for. They had already checked out a dusty, rowdy chicken pachanga up in the rural outpost of Sebastian, where they had declined to dine. After chowing down at Koppel’s, they headed out for more pachanga action. “No plan, just look,” said Garza cheerfully. “This time of year, anytime you see a lot of cars, you know there’s a political party. Besides, it’s the only time of year people will feed you free without questioning who you are.” Alexander got a far-off look. “You should have been at the Contreras’ pachanga,” he said regretfully. “They cooked a pig.”

A Very Personal Politics

I have seen the pachanga future, and its name is Richard Ruiz. This natty, gold-necklaced young man with a stylishly barbered beard and moustache owns and operates a vegetable-packing shed on Edinburg’s outskirts. Over the past six years Ruiz has refined the formula for the primary-season rally he throws for the candidates of his choice—twelve of them this year. He plans his parties with a file folder of meticulous lists encompassing menu, parking supervision, letters to the lucky candidates, and media contacts. Ruiz’s are modern pachangas, big and urban and sexually integrated, but beyond that, they’re slicked up to state-of-the-eighties art.

Last April, at a cost of more than $3000, Ruiz outdid himself. To shelter the party from the spring winds, he had his men clear the cavernous packing shed of cabbages and onions. He decorated the space with potted plants, flags, and bunting, engaged two bands, enlisted a professor from Pan American University and an accountant as masters of ceremonies, and set up two open bars serving mixed drinks—Johnny Walker Black and Jack Daniels Black, no less—along with the traditional beer. The fajita dinners grilled by Ruiz’s employees were served with Pace picante sauce and pico de gallo made with Ruiz’s cherished Texas onions; 1500 people came in response to his tasteful newspaper ad. “There were some off the streets we didn’t know, but a lot were good-quality people,” says Ruiz. “Sometimes, and I’m being perfectly honest, you throw a free barbecue and you get people you don’t really want.”

Two TV stations even turned up to cover the Ruiz pachanga. No wonder local and Valleywide candidates call at the Ruiz Produce Company all year to solicit support. “We don’t decide till we get ready,” says Ruiz, who makes the endorsement decisions for his extended family like a latter-day political godfather who has used pachangas to establish himself as a power broker. At the same time, he has set the pace for pachanga upscaling, a process similar to the transformation of political functions throughout much of Anglo Texas, where hot-dog-and-beer parties have all but been supplanted by teas and coffees.

As separate a world as it seems, then, the Valley is inevitably becoming more like the rest of Texas. Unlike the popular conception of the region as a uniformly dirt-poor expanse, the Valley taken as a whole is one of the most urbanized areas of the state. It is poor, certainly, and stricken with a shocking 15 to 20 per cent unemployment rate, but it comprises an almost unbroken chain of small cities from Brownsville and Harlingen across to Mission along U.S. Highway 83. Between 1980 and 1984 Cameron and Hidalgo counties were the second-fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the nation, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. The Valley population exploded by more than 50 per cent in the seventies, and nearly 600,000 people are here now.

Just as pachangas have changed to reflect the increasing urbanization of the Valley, so have Valley politics changed across the board. Even as solidly rural a tradition as the pickup truck caravan has taken a citified twist in some campaigns. Brownsville’s Rene Oliveira had a caravan this spring made up entirely of lowriders. Quite apart from indigenous Valley political forms, candidates are beginning to act more like upstate candidates, spending bigger bucks, allocating more of their budgets for television, and hiring professional campaign managers and ad agencies, both new developments down here.

In that changing environment, apostates say that pachangas may be dwindling in significance. One frequent gripe is that you see the same people over and over on the pachanga trail. Another is that in these days of special-issue politics, the pachanga doesn’t offer an environment for the discussion of volatile topics like education reform, a subject that Valley teachers raised unmitigated hell about during the May primary. Such concerns are better addressed by television, direct mail, or the rapidly proliferating candidate forums, those public question-and-answer sessions that take their cue from the activist Valley Interfaith organization’s “accountability sessions.”

Hands-on contact in the pachanga mode still looms large, though. Polling, that sacred rite of so many Texas politicians, is in its infancy here. Hector Uribe is almost the only Valley politician who routinely conducts polls; more typical is legislator Alex Moreno of Edinburg. “My poll is, I talk to people about how it’s going and I get a feeling,” he says. “Why spend $2000 to $3000 on a poll when for a TV budget of $3500 you can buy good spots? Or why not put your money into volunteer ladies, like most people, where for $2000 or $3000 a year you can pay a bunch of them for their gas and new tires, and they can make a real difference?” As for the phone banks so beloved in the rest of Texas, Moreno points out that they’re useless in places like Elsa and Edcouch, where many people don’t have phones.

All that is a far cry from upstate campaigning. It would behoove outside candidates to make note of the differences before descending on the Valley with their postcards, their phone calls, and their hotel receptions with ditsy hors d’oeuvres. And descend they will: Democrats and Republicans alike are fairly lusting after the Valley vote. As the state’s last overwhelmingly Democratic stronghold, the area is pivotal for statewide Democratic candidates. And with Republicans pursuing the culturally conservative Hispanic community, the Democrats can’t afford to take the Valley for granted anymore.

Finally, those who would woo the Valley vote should bear in mind that for the foreseeable future, although change is in the wind, the Valley style will remain joyously heated and personal. Newspaper ads drip with calumny, and even television spots adopt the personal style. The most-talked-about spring primary spots were those of scrappy young attorney Hector Villarreal, in which he depicted his opponent, county court-at-law judge Manuel Trigo, as a sliced-open, spilling sack of grain (trigo means “wheat” in Spanish) or lampooned Trigo’s record by showing a needle ripping across a wobbling phonograph disk. As to the fearsome realities of last-minute campaigning in the Valley barrios, well, let upstate candidates be mindful of the scurrilous hojas sueltas, the anonymous eleventh-hour whispering campaigns that call candidates every name in the book without fear of legal retribution.

What’s next? It’s only a matter of time before the all-but-unthinkable occurs: the Republican pachanga. On a recent flight to Harlingen, a young Reagan organizer in the Valley listened wistfully to his Democratic seatmates discuss the coming weekend’s pachangas and wondered aloud whether Republicans could plug into the pachanga circuit. His companions were highly amused. “Where would you hold it?” one asked with a snort. “The country club?” Five years from now that may not sound so funny.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Rio Grande Valley