David Hood had no idea what to expect when, in late 1973, producer Jerry Wexler told him and his band, fabled session men the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, that the next project booked into their Sheffield, Alabama, studio was country artist Willie Nelson. Wexler was considered “the godfather of rhythm and blues,” and the Swampers, as Hood and the boys were affectionately nicknamed, were an R&B band. Though they’d recently branched out to support such rock stars as Paul Simon and Traffic, they were still better known as the subtle, soulful backing group for acts like Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, and the Staple Singers. But then Willie showed up, bringing with him the eleven songs that would become his masterpiece, 1974’s Phases and Stages.

Subscribe

(Read a transcript of this episode below.)

On this week’s One By Willie, Hood talks about his favorite track on Phases, “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again,” and the whirlwind sessions in which he and the Swampers, augmented by select members of Nashville’s A-Team session players, backed up Willie for the first country album ever cut at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Phases was, of course, named Willie’s very finest album by Texas Monthly in our comprehensive ranking of all 146 of his records, and the subject prompts memories from Hood on Wexler, why the producer wanted to bring Willie to Alabama, and the weird moment when Willie first walked into the studio. Hood and podcast host John Spong also give a quick listen to an alternative version of Phases and Stages that was recorded in Nashville after the Music Row powers that be didn’t quite understand what Willie and the Swampers had accomplished. Spoiler alert: Wexler and Atlantic Records were wise to stick with the Muscle Shoals version when release time came.

We’ve created an Apple Music playlist for this series that we’ll add to with each episode we publish. And if you like the show, please subscribe and drop us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

One by Willie is produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, with production by Patrick Michels. The show is produced by Megan Creydt. Graphic design is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Transcript

John Spong (voice-over): Hey there, I’m John Spong with Texas Monthly magazine, and this is One By Willie, a podcast in which I talk each week to one notable Willie Nelson fan about one Willie song that they really love. The show is brought to you by White Claw Hard Seltzer.

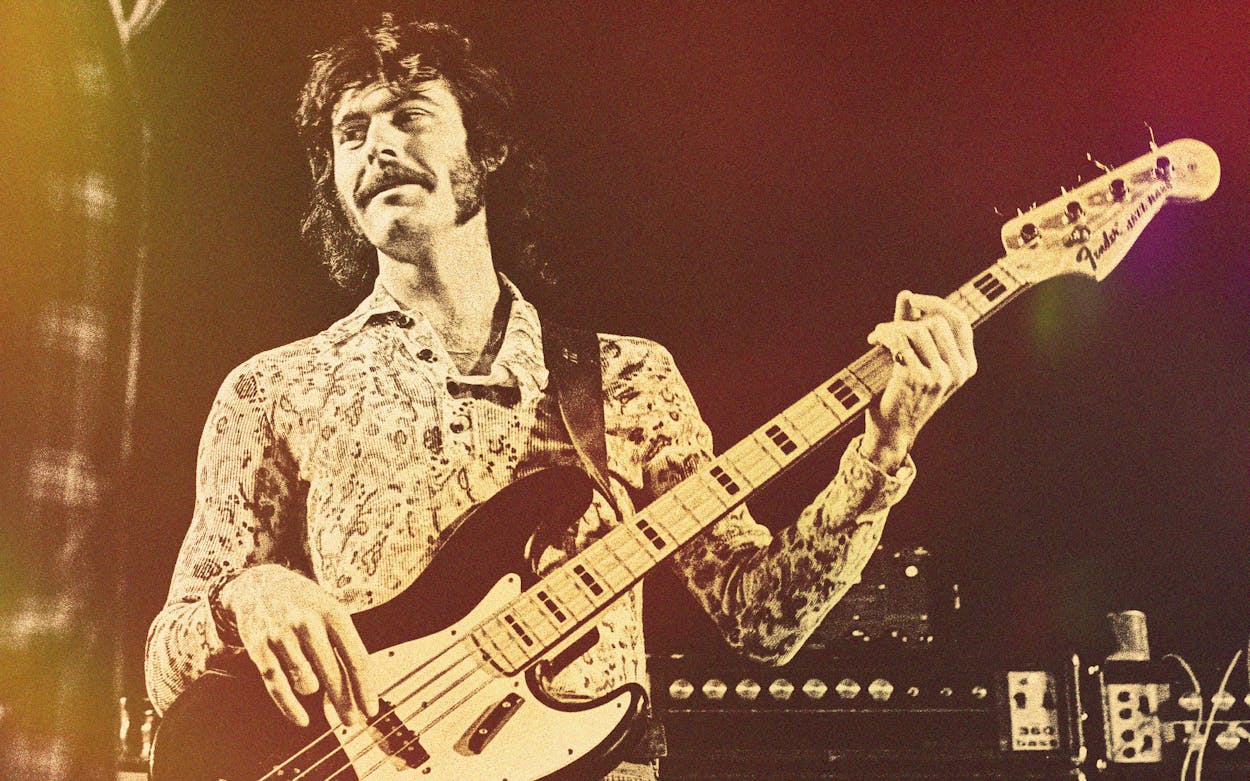

This week, we visit with legendary Muscle Shoals bass player David Hood about a classic Willie song that he played on, “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again.” David is, of course, one of the most important session players who ever lived, and as a member of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section—or as music lovers call them, the Swampers—he provided the soulful foundation to such know-’em-by-heart hits as the Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There,” Paul Simon’s “Kodachrome,” and Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll.” But what even some Willie nerds forget is that David and the boys—augmented by some members of Nashville’s A-Team—also backed up Willie on what me and many others consider to be his single greatest album: 1974’s Phases and Stages.

So get ready for David to explain why “Falling in Love Again” is his favorite track on Phases and Stages, how producer Jerry Wexler brought the album project to Muscle Shoals in the first place, and the weird moment when Willie first walked into the studio. Oh, and I’ll also play David a little bit of a bootleg I found of an alternative version of Phases and Stages. It was recorded in Nashville after the powers that be didn’t quite get what Willie and the Swampers had done, and boy, is the world ever lucky that Atlantic Records decided to release the Muscle Shoals version of that album. So let’s do it.

[Willie Nelson singing “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again”]

John Spong: If I say, “What’s so great about ‘(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again?,’ what’s the answer to that?

David Hood: Well, it’s a beautiful song. Beautiful melody and a great message. It reminds me how great Barry was. Keyboard player.

John Spong: Yeah.

David Hood: Because we never considered ourself in any way country musicians. Well, I’ll tell you the list of people that we worked on that year. Willie Nelson is the only one that even comes close to being country. And we didn’t really listen to country that much, but if you live here, you can’t help but hear it. But we were not—we were cool, hip R&B players.

John Spong: How did that record come to you? How did you guys get enlisted to work on this?

David Hood: Well, we worked with Jerry Wexler a lot, on rhythm and blues artists. And Jerry Wexler was a big western swing fan. Nobody knows that about him, but he was also a country music fan. And what he really was, was a great songwriter fan. He picked good songwriters, good stylists. And he loved Willie. And Willie had not really had any hits on himself at that time. He had written them for other people, but no hits on himself.

John Spong: Well, and so, for our younger friends, who was Jerry Wexler? I hate to think somebody doesn’t know who Jerry Wexler was, but just in case, who was that?

David Hood: Well, he was the godfather of rhythm and blues. But his official title, he was executive vice president at Atlantic Records. He was a partner with Ahmet Ertegun, and Nesuhi Ertegun, Ahmet’s brother. And he worked with everybody, from Ray Charles to Aretha Franklin. I mean, he was a heavyweight producer, and we loved working with him. And he loved us, apparently, for him to bring something like that to us to record.

John Spong: Well, y’all had been working with him for years, right? Because, I mean, go back, Aretha, and Wilson Pickett, and the people you were just mentioning, but a whole host of others.

David Hood: Yes. And he later did Bob Dylan. He did Dire Straits. He did all kinds of things, but he picked the ones that he loved. Like, this album here was one of his favorite albums, and it wasn’t a hit. And he liked hits, and he liked to make money. But he loved this album. He told me before he died, it was still one of his favorite albums that he had worked on.

John Spong: Oh, that is monstrous praise. That’s huge.

David Hood: Yeah, it is.

John Spong: And so, if I remember the history right, what kind of happened is—I mean, everybody, at least in Texas, is familiar with the fact that Willie kind of floundered in Nashville. He got those cuts, like you said, which made him a fair amount of money. He had lots of success as a songwriter, but his own records hadn’t sold. And the legend is that in October of ’71, it was CMA Awards week in Nashville, and there was always a big party at Harlan Howard’s house. And they would have guys pull out their guitars and do stuff. And Wexler was there, and Willie came out. And if you already know all this, stop me, because I would much rather hear you tell this story than me.

David Hood: Well, I’d like to hear what—no, I don’t know this.

John Spong: Oh, cool. So yeah, Willie comes out, and he’s been struggling. And his last album had been released earlier in the year, and it was Yesterday’s Wine, which is also a concept album, but it was kind of weird. And RCA didn’t like it, and they didn’t push it, and Willie’s like, “I think this thing’s over with RCA.” So he sees Wexler across the room, and he plays much of Phases and Stages, this song cycle that he’s working on. And Wexler came up to him afterwards and said, “That was good. We’re about to start a Nashville division for Atlantic. I want you on my label.” And Willie said, “Sure. Yeah, I’ll do that.” And so here comes the next chapter of Willie’s career.

But one of the things that was interesting to me as I was thinking about all this before talking to you, the first record—so Willie entices Wexler, gets him interested with this concept album that he plays, and these songs that y’all worked on. But when they go into the studio for the first time, which I think is in early ’73, they go in New York, and they cut Shotgun Willie instead. And they cut it with Willie’s own band, you know? And so they didn’t go with the heady concept record, maybe in part because Yesterday’s Wine had stiffed so badly.

But the other thing that’s interesting to me is that getting to record with your own band was kind of the hallmark of creative control, at least as far as Nashville was concerned in ’72, and that’s what the artists were griping about. And so Willie’s first thing is the first record he ever makes with his own band, his touring band, but then the next record is with you guys. And I wondered if you know anything about how that choice was made. Was it just that Jerry loved you guys so much and knew how good you were?

David Hood: Yeah, I think that we were his boys, more or less—Wexler. But he knew it was a leap for us to be doing this kind of music because we’re more rhythm and blues and rock players, but he loved Willie’s songwriting, and he just thought it was a great idea. And when he first brought Willie to us, Willie drives up from Texas in this dusty, dirty Mercedes Benz. And comes in with his guitar and his suitcase, and throws it on the floor and says, “Let’s cut.” And he wants to do the whole thing, start to finish. And we said, “Wait, wait, wait. We’ve got to learn each song and do it like that.” And he didn’t really want to do it that way, but there was no other way we knew how to do it.

John Spong: Oh my God.

David Hood: But he wanted to go start to finish, like a live performance. And that would’ve been wonderful, but we had to learn the songs.

John Spong: [Laughs] Well, I love that. Did he tell you what the album was about?

David Hood: Well, he told us—yeah, he did tell us. It was the guy’s side and the girl’s side. And it was a concept album. And at that time, I didn’t really know what a concept album was. I thought Tommy by the Who was a concept album, and maybe Sgt. Pepper’s or something, but I didn’t really know there was such thing in country music. But we were very flattered to get to be working with him. We knew who he was, even though he hadn’t had any hits of his own at that time.

John Spong: And you mentioned the concept, and so, yeah, it’s a concept record, and it’s a divorce record, and side A is the wife’s side. And side B is the husband’s side, as they’re breaking up. And it’s interesting because on the woman’s side, there’s a lot more soul-searching, and hurting, and trying to think about it. And on the man’s side, he just kind of thinks, “Huh? How did this happen? I better go get drunk.” And “How am I going to move on?” He doesn’t give himself to quite the reflection that the wife does on her side. Were y’all even listening—doesn’t sound like you were paying much attention to the lyrics in the studio, though.

David Hood: Well, we were listening, but not really. We were trying to learn the music. It was much later when I thought, “Wow, there’s hardly any lyrics in that song.” If you look at the lyrics, there’s very few lyrics. The melody is beautiful.

[Willie Nelson singing “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again”]

John Spong: With the song itself, one of the things that gets me about it is—and I think it gets at one of the things that’s special about what Willie does—it’s a country song, especially as y’all arranged it, but I talked to some musician buddies, and they were explaining the melody of that song to me. And they said, “Well, yeah, it’s basically a three-chord song. But when you start adding in some of what they call diminished chords and things like that . . .” And the moment they all brought out was where Willie sings, “And I may beeee making mistakes again.” When you add all that stuff in, it’s actually a ten-chord song, which is not country music.

David Hood: Yeah. It has some R&B flavor to it. And we were trying our best to be simple. The country music, you know, if you play too much, it’s no longer country. And I think we did that pretty good. If you could isolate the tracks, you’d hear that—I mean, it’s very, very simple what we were doing, with the exception of what Barry did.

John Spong: Right. On the piano?

David Hood: Beautiful piano. Yeah. And working with people like Johnny Gimble and Fred Carter on the acoustic guitar, and Weldon Myrick on the steel guitar—they’re classic country musicians. They’re probably A-Team in Nashville at that time.

John Spong: And was it Weldon or—because John Hughey’s on the record too, right?

David Hood: Yeah, John—well, it was both of them. I don’t know which one that was on that particular song.

John Spong: Well, and that’s the thing, yeah, because it’s you and Pete Carr on guitar; and Roger Hawkins on drums; Barry Beckett, who we’ve mentioned, on piano. But then, I guess to make sure it sounded country—but also because Nashville players are so good—Wexler brought in, it looks like Fred Carter on guitar, John Hughey on steel, and Johnny Gimble on fiddle. Did you already know those guys or of those guys?

David Hood: No; we had heard of them. And I think Weldon Myrick also played on this, because John Hughey couldn’t be there the whole time.

John Spong: And what’s the relationship—relationship’s the wrong word, but was what they did in Nashville similar to what you did in Muscle Shoals? I mean, just being the studio guys and working fast—did you have a similar process?

David Hood: Yeah, we did work very fast. I mean, most things we would cut, we’d get the first take. And I’m talking about big hits, like “Kodachrome.” That was probably a first or second take. And so we were used to that, but we weren’t used to doing that in country music. But the guys in Nashville were.

John Spong: Well, especially on this song, the interplay between the steel and Beckett’s piano—I’ve listened to that song with like some hard-core Willie nerd fans, and they just assume that’s Willie’s sister, Bobbie, playing the piano.

David Hood: No.

John Spong: And Barry put such a, in my mind, church music quality into it. It’s Southern church. It’s gospel, almost, which lends something to that recording.

David Hood: Yes. Barry was a brilliant player. When we first met him, we brought Barry in to replace Spooner Oldham on keys, because Spooner was moving to Memphis to work with Dan Penn. And we looked for different piano players, and Barry was the one we picked. But we said, “Look, man, you’re a little too country. You need to get more rhythm and blues.” And we got him to listen to some Ray Charles records and some R&B records and said, “Take all that frilly stuff out of it, and funk it up.” And he did. But the other comes out on this record.

[Instrumental clip of “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again”]

John Spong: Did you do anything to prep for Willie?

David Hood: No. No. I mean, we never did with anybody. People would come in cold; we would hear the songs for the first time when Barry was writing down the chords to make our chord charts. And we would go in cold, and just cut it right then. And I mean, that amazes me to this day. And at the time, we didn’t really think anything about it. We just thought, “Well, that’s what we’re supposed to do.” But now when I look back on it, I think, “Damn, how’d we do that?”

John Spong: Well, it’s the way the Nashville guys did it too. Although they would typically be familiar with the artists coming in, and these guys had already worked with . . . I mean, Johnny Gimble was an old buddy of Willie’s, and so they knew what to do with him. And I guess . . . did they serve as translators for what he was doing, to an extent?

David Hood: Yeah, I guess so. I mean, if you were to take Johnny and the other guys off of it and just heard our tracks, they would sound like R&B tracks, almost.

John Spong: Interesting.

David Hood: If you took the country musicians off there.

John Spong: Well, and so how many days were y’all working on this?

David Hood: I think about three days.

John Spong: Wow. Would y’all have hung out with Willie after recording sessions? Or did y’all just go home?

David Hood: Yeah, we probably went home. We might have hung around a little bit, but there’s nothing to do here. That was the reason I think we got a lot of work done. It’s just a small town. And at that time, it was a dry county. You couldn’t even go get a drink. And usually, by the time we would get through working, we’d just all go home. Willie probably stayed at the Holiday Inn or the Howard Johnson’s. It’d be one or the other at that time.

John Spong: Did he have a big entourage, or did he come by himself?

David Hood: Oh, no. Came by himself. He was just like one of the guys. You know, Texas is not that far from Alabama.

John Spong: So, what was he like at that period? Because he’s not Willie Nelson yet. He’s clearly not a big star, and he’s not actually just had a whole lot of difficulty, and kind of obstacle after obstacle, trying to make it as a performer. But he’s just moved to Austin, he’s just added his sister to the band, Shotgun Willie‘s out, and that feels good. This may be too long ago to remember, but did he feel like he was in a state of flux? Or did he feel like he had some momentum? Or was he just an artist getting his thing done?

David Hood: I think he was an artist getting his thing done, but I think he felt very comfortable with us after he saw that we could play. When people first walk into the studio, and it’s just four white guys sitting there, they don’t know what we’re going to do. I mean, believe me, a lot of Black artists we worked with the first time, they’re thinking, “What? These guys are going to play on my record?” And he probably thought the same thing.

John Spong: It occurs to me, something I forgot to mention earlier, as we talk over Zoom about this stuff, where are you sitting right now?

David Hood: I’m in the control room of our original studio at 3614 Jackson Highway, in Sheffield, Alabama, which is the Muscle Shoals area. And the studio is called Muscle Shoals Sound. And when we bought the studio, we were trying to think of a name, and we thought Lone Pine, because there’s a pine tree in the parking lot. Came up with all these different names. And I said, “I know—Muscle Shoals Sound.” And everybody just laughed, because there was no such thing as the Muscle Shoals Sound at that time. But the next day we came in and said, “You know? That’s not a bad name.” And so that’s how it’s got its name.

John Spong: And so, then what? A couple years after that is when the Rolling Stones passed through and cut Sticky Fingers there?

David Hood: Actually, less than two years. It was, uh, ’73, I guess.

John Spong: But at any event, you’re looking through the window into the room where you cut Phases and Stages with Willie.

David Hood: And also, looking in the room where the Stones cut “Brown Sugar,” where Bobby Womack cut a bunch of his hits. The same room where Traffic cut Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory.

John Spong: Wow.

David Hood: Same room. It looks exactly the same way, too, because we restored it, and it looks exactly like it did in 1970, ’72.

John Spong: Oh wow. Who was in charge in the studio? Was Wexler?

David Hood: Wexler. Wexler. It’d be Wexler, and then Barry would make the chord charts. And we’d be listening while Willie was playing the songs down. And they’re all little bits and pieces, like Phases and Stages, the theme, and then he’d . . .

[Willie Nelson singing “Phases and Stages (Theme)”]

David Hood: And then, there goes another Phases and Stages. And it was all those little bits, and we had to cut them all together.

John Spong: But it sounds like he did have a pretty complete vision—that he knew what he wanted.

David Hood: Yeah, I think he did.

John Spong: Did you end up recording them in order, or do you remember?

David Hood: I don’t remember if it was in order, but it probably was, because that’s the way he played it down to us. I remember when we first heard “Bloody Mary Morning,” we thought, “Wow, now there’s a hit. That’s a hit record right there.” And also, we liked the one of “Little Sister’s Coming Home,” and “Down at the Corner Beer Joint.” Those were fun songs to us. Yeah.

John Spong: Well, yeah, that’s Texas dance music.

David Hood: Yeah.

John Spong: That’d be in line a little bit with that western swing that Wexler liked some much. Do you remember—did you get an impression of Willie’s guitar picking while he was in there? Because he played Trigger, not as pronounced or prominently as on other records, but he’s on guitar in there.

David Hood: Yeah, he is. And we thought, “Gosh, his timing is crazy.” We thought we had to be metronomes, and he was all over the place.

John Spong: I wondered, did he follow you or did you follow him, or did you just kind of try to tune him out when he was picking?

David Hood: Well, a little of both, I think.

John Spong: When I listen closely to this song, and to his vocal lines in particular, what he is singing has absolutely nothing—more than usual, even—it has nothing to do with the time signature of the song and what else is happening in the room. It’s amazing.

David Hood: Right. And for that reason, he was a little difficult to play with. And in some ways, he had to compromise and play with us. I consider Willie one of the better artists I’ve worked with, but he was definitely his own guy. He didn’t go by the book, necessarily. He wrote the book.

[Willie Nelson singing “Bloody Mary Morning”]

John Spong: Are you familiar . . . There’s a legend out there that after this was recorded—I don’t know what the legend is and what the truth . . . well, I think I know what the truth is. There’s this idea that Wexler took it back to Nashville, to Fred Carter’s studio there, and that they rerecorded some of it. Have you ever heard that, or do you know anything about that?

David Hood: Nah. I mean, the tracks on this album—it’s us. I mean, it’s us all over it. I think they might have tried to rerecord something, but the tracks that are on this album are us. I mean, that’s like hearing your best friend talk—you recognize their voice. Like I said, Roger and I tried to play as straight as we could, because we were used to playing rhythm and blues, and that was a different thing. So we were keeping it as simple as we could. Because to us, that’s the way country music sounded. It was very simple and straight ahead.

John Spong: Yeah. Well, yeah, it’s not the bass line to “I’ll Take You There,” anywhere on there.

David Hood: No. No. And it was about the same time. “I’ll Take You There” was the year before, but it was about the same time—in dog years, especially. It was just two years apart.

John Spong: Right. Actually, I found . . . If you look online, if you go digging, of course you can find anything online. There are ideas out there that maybe Willie took his own band into the studio in Nashville, and they rerecorded the whole thing. And I was like, “I don’t think so.”

David Hood: Well, what’s on this album is us, because I’ve heard the other versions of these songs. I thought, “Gosh, that’s not s—.”

John Spong: [Laughs] That’s exactly—

David Hood: I calls them as I sees them.

John Spong: No, that’s exactly where I was headed. I mean, I love this album. I love these songs, and they’re so familiar to me. And when I listened to the version that was recorded in Nashville—oh, my . . .

David Hood: Yeah. Yeah. Wexler sent me a copy of all that stuff. And I thought, “Gosh, those guys were nowhere.”

John Spong: Yeah. And this record—it’s kind of cool, because like you said, you guys were trying to play it straight, but also play it simple, and kind of stay out of the way and be more like a country thought. Well, one of the hallmarks of country music in those days was big strings, and choirs, and lots of stuff. And when they took it to Nashville, they made it sound like just another Nashville record from that period—and not a very good one, either.

John Spong: Let me see if I can find this, actually, because . . . I won’t ask you to listen to the whole thing, but—

David Hood: Good.

John Spong: That, I mean, it’s . . . My music folder. Let me see what I can do here.

[Willie Nelson singing alternate version of “Bloody Mary Morning”]

David Hood: Hooh!

John Spong: That piano—that’s terrible!

John Spong: Turn it off. How do you turn it off? It won’t turn off. Where’s it playing? I can’t get this thing to . . .

David Hood: That sounds like a real bad country music demo.

John Spong: It really does. Somebody should have gone to jail for that.

David Hood: Yeah. I’ve got all that stuff. Wexler sent me that stuff, and I’ve got it somewhere. It just sounds like really bad outtakes or bad demos to me.

John Spong: Yeah. It didn’t work. Well, and that’s the thing, because—and we talked about this on the phone before today—when Texas Monthly ranked all, at the time, 143 Willie albums, and now we’re up to 145, actually, we did—we picked Phases and Stages the very best Willie record ever released.

David Hood: Wow. That’s something. I’m flattered by that. I also see listed on here, Al Lester replaces Johnny Gimble on fiddle. Al was a barber here in town, and he played bluegrass music.

John Spong: What?

David Hood: He wasn’t even a full-time musician. Yeah. But we knew he was a good fiddle player, but he didn’t play on any of the records I played on. He played bluegrass, and he was a barber. That’s how he made his living.

John Spong: I had no idea. I wondered why I hadn’t seen him in many other credits, certainly not in any other Willie credits.

David Hood: Well, no, he wouldn’t be Willie, but we did work with him other times—but it was on stuff where we thought, “Well, let’s get Al to come in and play fiddle.” He was not one of the regular guys.

John Spong: Oh wow.

David Hood: But he’s probably the only person I knew that played fiddle at that time.

John Spong: Wow.

David Hood: You know, we may be two hours from Nashville, but we’re a million miles from Nashville. We’re much closer to Memphis in the music and the style.

John Spong: It’s interesting, because that’s what I’ve always thought, and that’s one of the other things that’s such a great accomplishment about this record. It’s its own thing. But that’s what y’all did. When people came in, you figured out what they were going to do, and you worked with them, and you worked in support of them, and you got it.

David Hood: Yeah. It was a golden era in my life, I think. And I’m a little too old to be trying to do that again, but I’m really proud of what we accomplished.

John Spong: Would you say that this record ranks up there with the best records that came out of your studio?

David Hood: Yeah. Yeah. I would. I mean, it’s different from, say, the Staple Singers, or Aretha Franklin, or Bobby Womack, obviously, but I think it’s just as good a record as any of the other things I’ve worked on, or is maybe one of the best. And I’m very proud of what we did. I’m not bragging. I’m really proud of it. It wasn’t a hit. If it’d been a hit, I’d really be bragging about it. But I wouldn’t have made any more money. A musician, a sideman, like me, we make union scale, and that’s it. It’s over.

John Spong: Right.

[Willie Nelson singing “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling In Love Again”]

David Hood: Well, I’ve enjoyed this. It made me research what we did with Willie. And like I said, 1973—there’s a lot of water under the bridge since then. But I enjoyed going back and looking this stuff up.

John Spong: Well, hopefully it made you proud, because it really is a special thing, and y’all did it.

David Hood: Well, it does make me be proud, because it’s, like I said, one of my favorite albums that I’ve worked on, out of almost a sixty-year career.

[Instrumental clip of “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling In Love Again”]

John Spong (voice-over): All right, Willie fans. That was the legendary David Hood, telling us all about “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling In Love Again.” A huge thanks to him for coming on the show. A big thanks also to our sponsor, White Claw Hard Seltzer, and a big thanks to you for tuning in. If you dig the show, please subscribe, maybe tell a couple friends, and visit our page at Apple Podcasts and give us some stars. Oh, and please also check out our One By Willie playlist at Apple Music. And be sure to tune back in next week to hear none other than Norah Jones talking about one of her favorite old Willie cuts from the early sixties, “Permanently Lonely.” . . . We will see y’all next week.