Long before Texans had heard of “no pass, no play,” and before free trade was a major political issue, the diminutive Dallas billionaire H. Ross Perot entered my life as a super-patriot who believed perseverance was the key to success.

The date was June 17, 1970, and I was receiving my Eagle Scout award in Dallas. If I had ever even heard of Perot, it was only because North Vietnam had turned him away the previous Christmas when he tried to deliver gifts and supplies to American POWs held in Hanoi. But Perot had also recently donated $1 million to the Dallas branch of the Boy Scouts of America. So when I opened my case containing an eagle pendant dangling from a red, white, and blue ribbon, there also was a printed note from Ross Perot. It read: “This major accomplishment establishes you as one of America’s future leaders. I will be watching your continued progress . . .”

As it turned out, Perot spent no time watching me, but I spent much of my adult life watching Perot. I covered him during his two presidential campaigns and kept up with his other political and business ventures over the decades. He was one of those Texans who operated on a grand scale: disrupting business, improving public schools, and injecting into presidential politics a new approach to economic populism.

In some ways, the former computer magnate, who died on July 9 at the age of 89, was the beta version of Donald Trump. Trump wants to “drain the swamp.” In 1992, Perot said it was time to “pick up a shovel and clean out the barn.” Trump overturned Republican orthodoxy to attack the North American Free Trade Agreement. Perot warned that NAFTA would create a “giant sucking sound” as jobs moved south to Mexico.

But that’s where the comparisons end. Perot did not believe that America had to be made great again. As his note to me stated, the United States was “the greatest country in the world.” Perot was also a Cassandra, warning that the national debt, if left unchecked, would ruin the U.S. “The debt is like a crazy aunt you keep down in the basement,” Perot said. “All the neighbors know she’s there, but nobody talks about her.” Trump once bragged that he was “the king of debt,” and he has proved it by letting the national debt soar on his watch.

I once heard a joke that Perot was a self-made man: he worshiped his creator. And yet he possessed a humility and prudishness that are totally lacking in our current president. Perot held on to a tattered copy of the Boy Scout handbook from his youth, relishing its principles of good deeds and honor. In 1955 he sought early release from the Navy because of the propensity of sailors to swear, drink, and commit adultery. He bought his suits off the rack.

Just five feet five inches tall, with distinctive jug ears and a nasal twang common to Texarkana, where he was born in 1930, Perot was widely and easily caricatured. If you were sentient in the nineties, you probably remember Dana Carvey’s frequent send-ups of Perot on Saturday Night Live. Perot got a kick out of the parodies, once describing himself as “a latter-day P. T. Barnum with no elephants.”

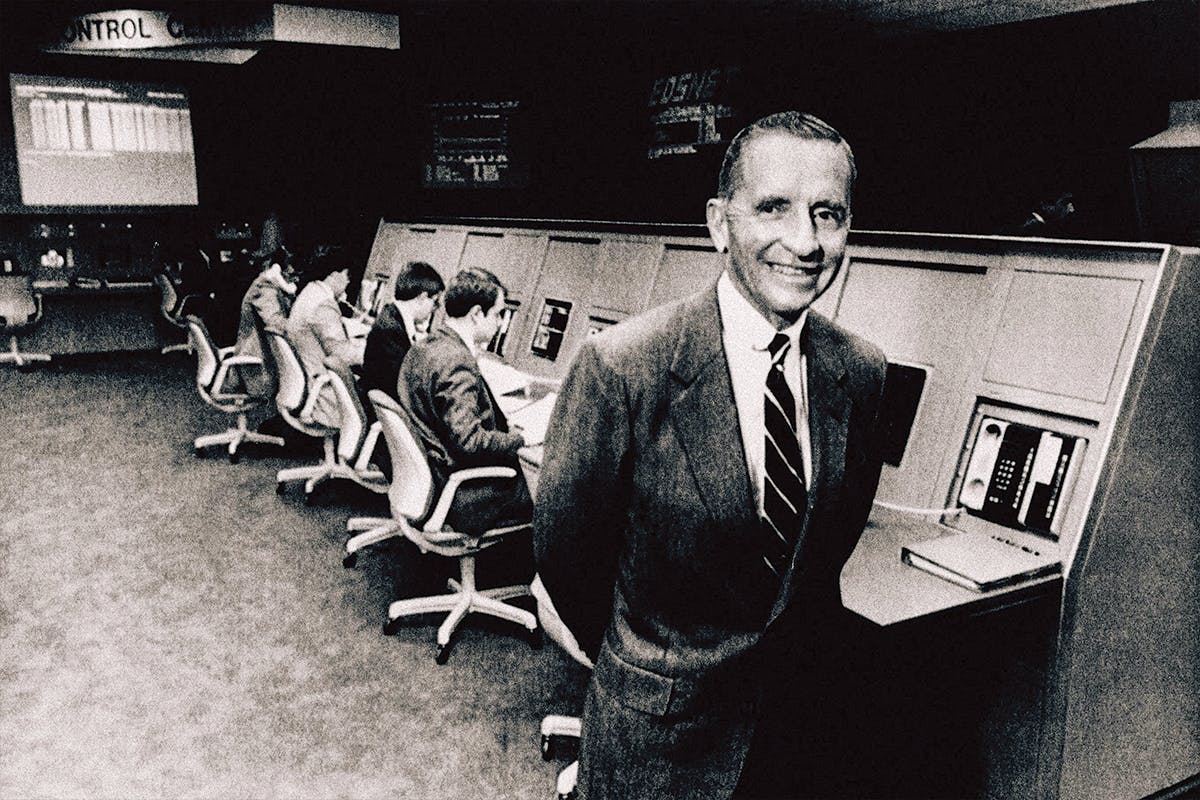

After leaving the Navy in 1957 (his request for early release had been denied), he went to work for IBM as a computer salesman. He reportedly sold so many computers that IBM capped commissions. His superiors weren’t interested in his ideas for selling services as well as machines, so in 1962 Perot left IBM and founded Electronic Data Systems, in Dallas. EDS developed outsourcing so that businesses and government agencies didn’t have to employ and constantly retrain their own technology departments.

EDS made Perot a billionaire. He once called money “the most overrated thing in the world,” which is easy to say if you’ve got it. But those close to him agreed that Perot loved the work of building a company more than the personal fortune it brought him.

His wealth and business acumen also earned him a seat at the public policy table. In 1984 Perot was appointed by then-governor Mark White to chair a committee to study improvements in public education. He insisted on reforms such as literacy testing for teachers and adding prekindergarten to Texas public schools. But perhaps his most lasting, and controversial, achievement was “no pass, no play,” the rule that students must have passing grades to participate in extracurricular activities, including football. “If the people of Texas want Friday night entertainment instead of education, let’s find out about it,” Perot declared, as he fought opposition from football coaches.

The 1992 presidential race would be Perot’s biggest stage. Perot had become disillusioned with both major national political parties, believing they represented only the wealthiest Americans. The national economy was in a crisis, he said, promising to “git under the hood” and fix it.

What Perot could not fix was his own campaign for president. He entered the race as an independent. He dropped out. He got back in. The campaign seethed with paranoia, and Perot became more and more aloof. Bill Clinton ended up winning, though Perot’s 18.9 percent was the best showing by an independent or third-party candidate since Teddy Roosevelt ran under the Bull Moose banner in 1912.

When Perot ran again, in 1996, he did so under the banner of the Reform Party, which he had founded the year before. The supporters I met in California were new age, crystal-loving yuppies who seemed to believe Perot was about to usher in the Age of Aquarius. At the national party convention in Pennsylvania, the crowd was much more straitlaced, with many costumed as Betsy Ross, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln. In retrospect, these were the same kinds of folks who would go on to form the tea party.

After the Reform Party nominated nativist Pat Buchanan to run for president in 2000, Perot turned his back on the party he created and went into a self-imposed political exile that lasted for much of the rest of his life.

Instead, he focused on good deeds. The philanthropy that Perot began in 1969 carried on throughout the years, making Dallas a better place. He gave millions of dollars to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Perot Museum of Nature and Science. In 2017 alone, the Perot Foundation gave away $8.5 million to nonprofits and charities.

Perot died a rich man at a ripe old age. That’s more than most accomplish. But he can also lay claim to being one of the most Texan of Texans in the latter part of the twentieth century. Unlike many Texas men, he didn’t wear cowboy boots to make himself taller, but he was nonetheless a giant.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- Obituaries

- Ross Perot