It was past midnight in the Bexar County city of Windcrest, and resident Scott Lee-Ross had finally decided to stop staring at the weather report and go to bed. The rain—the type of constant drizzle that humidifies the air and soaks every crack and crevice with moisture—had been exhausting to deal with. “It’s the worst weather you can think of for this,” he told me via phone a few days later, after the stress of those hours subsided. Although rain is a blessing any time of year in South Texas, for the hundreds of light-show competitors whose houses turn the town into a mini Times Square each December, winter rains can really kill the cheer. Lee-Ross’s 25,000 lights of all colors, shapes, and sizes take 21 computers to run (which cost him less than you might think, thanks to the magic of LED bulbs). But the connections between the computers and the light show can corrode quickly if they get too wet. “If you don’t get replacement parts in time, boom, no lights,” Lee-Ross says. No lights on judgment day—November 29—would be very bad indeed.

A decade ago, Lee-Ross and his husband, Nathan, lived outside San Antonio in Selma, but Windcrest, a municipality twenty minutes from the River Walk, was always on their minds. The Fourth of July parades, town hall meetings, and mid-century architecture appealed to the couple. It all created, as Lee-Ross puts it, the vibe of a place “stuck in time.” But Windcrest possessed more than a small-town feel: it was the holiday magic the Lee-Rosses couldn’t resist. “We wanted to live in a place that valued Christmas, and there is nothing more important in Windcrest than Christmas.”

Windcrest’s reputation as a vibrant holiday town is cherished in South Texas. Every year, residents spend thousands of dollars collecting blow-up Santas, six-foot candy canes, and massive Disney characters to compete in Light Up, the neighborhood’s holiday decor competition. This year’s theme is “Fiesta de Navidad,” a nod to San Antonio’s week-long party in the spring, and locals have gotten into the spirit with altars wrapped with fabric from Mexico and star-shaped piñatas. Homeowners compete in one of several categories: Religious/Joyful (nativity scenes and the like), Charlie Browniest (all things Snoopy and friends), Clark Griswold (any and everything, to excess), Cul-de-sac/Block (a streetwide team-up), Nostalgic/Handcrafted (era-themed or homemade decor), and Martha Stewart Would Be Proud (elegant and timeless).

Residents go all out. Some employ actors or perform in their front-yard scenes themselves, sitting for hours as Mr. and Mrs. Claus. Some opt for traditional life-size reindeer, angels, and manger scenes; others use their imaginations—this year, a twelve-foot blow-up Santa is posed selling tacos from a truck next to a bear in a festive hat. The Lee-Rosses’ scene from Disney’s Frozen features several blow-up Olafs, the movie’s name in lights on the roof, icy blue strands forming Christmas trees across the yard, and “Let It Go” playing on a loop. It’s not prize money the couple is after, because there is little of that—a few hundred for winners and a celebratory dinner in January. It is the awe of the visitors, the happy faces of the children, the hundreds of cars stopping to admire months of hard work . . . and, of course, the bragging rights.

Light Up dates from the municipality’s birth, in 1959, when San Antonio residents Barbee and Murray Winn, the owners of several businesses, including Winn’s variety stores and Murray’s Candies, incorporated two square miles of land east of downtown. Barbee, an energetic woman with a creative streak, wanted to draw attention to their new town, and she purchased four hundred strands of Christmas lights to hand out to the neighbors. The genius marketing worked, because the decade between 1960 and 1970 saw Windcrest grow by more than 660 percent. Another of Barbee’s creations, the Windcrest Women’s Club, still plays a large role in the light show, choosing the judging panel and themes every year. Patricia Mowery, the club’s current president, reports that December sees a boost in applications, most likely due to the glitz of the holiday lights and the chance to take part in the planning. Each year’s theme is announced in January, giving homeowners the opportunity to score blow-ups and strands of colored lights on sale at Home Depot.

Last year, Windcrest went national when a local couple won $50,000 in ABC’s Great Christmas Light Fight contest, and the streets are likely to be even more packed this year as a result. It’s been estimated by city officials that 25,000 vehicles pass through annually, a staggering number given the size of the place. But the traffic, an unpleasant side effect of any popular event, traps residents in their homes from dusk to dawn. “Once the sun goes down, you aren’t leaving until morning,” Lee-Ross tells me matter-of-factly.

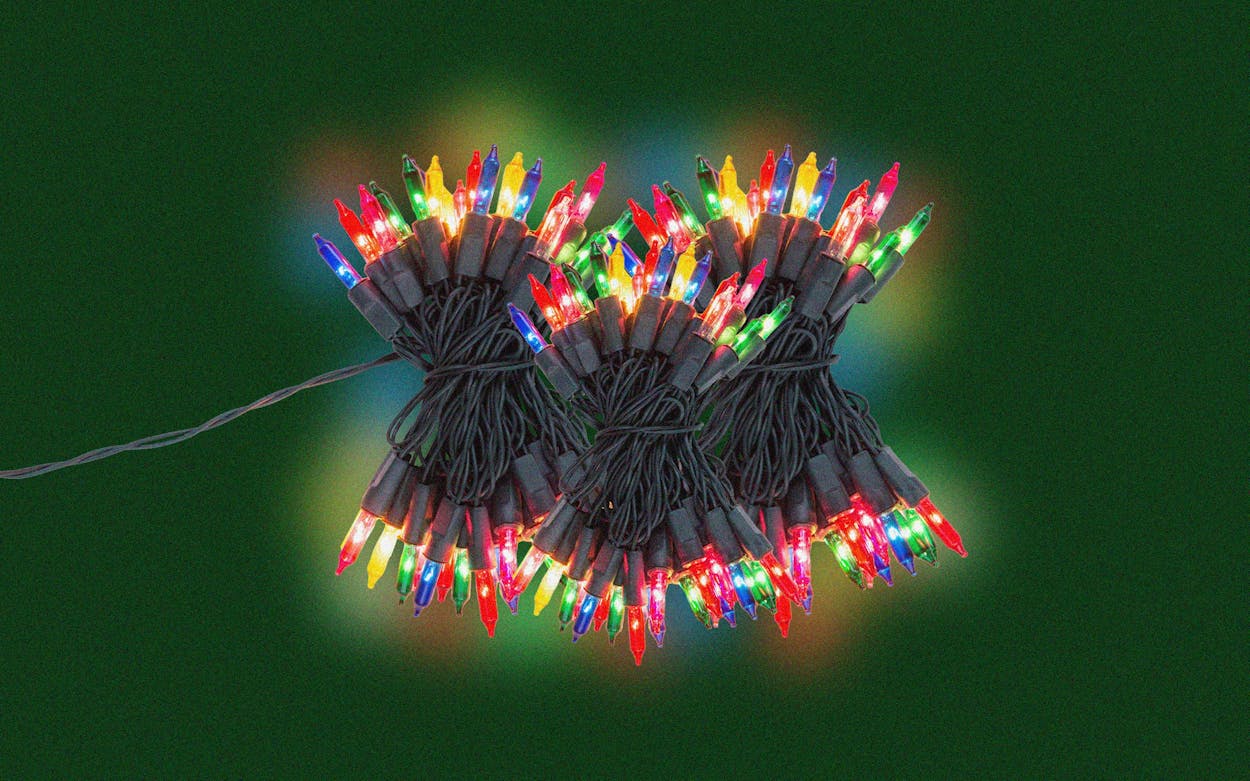

John and Brenda Wilson, longtime Windcrest residents and the Light Fight winners, took a well-deserved break this year from the preparation and cost, but Scott and Nathan Lee-Ross—who typically spend a thousand dollars a year for decor and miscellaneous items related to running their light show—were just getting started. Their annual Frozen display had won first runner-up in the Clark Griswold category several times, but they had never won first place. This year, they were determined to do just that. They knew it wouldn’t be easy; last year, the winning Griswold yard was filled with Santas of all sizes, elaborate arches, a bench for selfies, and wreaths so bright they had visitors shielding their eyes. Every square inch of this yard was covered in some sort of holiday ornamentation, but Scott Lee-Ross had a new tool in his Griswold belt: blow-up versions of the cast of Encanto. The Lee-Ross prep begins each year over Memorial Day weekend, although really, it never stops. “Some people golf; some people garden; we buy Christmas lights,” he laughs. Hours before the judging, he watched from his window, fretting as puddles filled around Bruno and Luisa, his leaf blower on standby to dry vulnerable decor.

Before Light Up officially kicked off on the first Saturday in December, a panel of judges made up of CEOs, local celebrities, and various other top brass from around San Antonio were driven through the streets and past the participating houses, marking their thoughts in little notebooks. Talking was discouraged, to avoid any undue influence between judges. After the final tally was made, the judges were dismissed and delivery of the yard-sign trophies began. This was the moment Scott Lee-Ross moved to Windcrest for—the dusk lockdown, the thousands of dollars, the rooms and closets and sheds dedicated to storage were all worth it. “After 5 years, our goal has been achieved,” their Facebook post read the next day, a small sign in their yard indicating first place in the Clark Griswold category. A little Disney magic was all it took.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- San Antonio