When the Kansas Jayhawks strode into Darrell K Royal–Texas Memorial Stadium to play the Texas Longhorns on the first Saturday in November, the surrounding Forty Acres was in a state of unprecedented upheaval. University of Texas head coach Mack Brown had followed three dissatisfying seasons with a calamitous start to the current one, and though he appeared to have righted the ship—his Horns had reeled off four straight wins, including a thrashing of OU—many fans seemed to be rooting for him to lose and make way for a new regime. Brown’s buffer at Bellmont Hall*, longtime athletic director DeLoss Dodds, had recently announced his retirement, and his champion at the Main Building, university president Bill Powers, was locked in a pitched battle with a faction of the nine-member board of regents who sought his ouster, all of them appointees of former Aggie yell leader Rick Perry. Even this Kansas game, a presumed gimme, wasn’t going quite right. After a sluggish first quarter, the Horns had found the end zone twice in the second, only to give up a late Jayhawks drive and field goal to close the half.

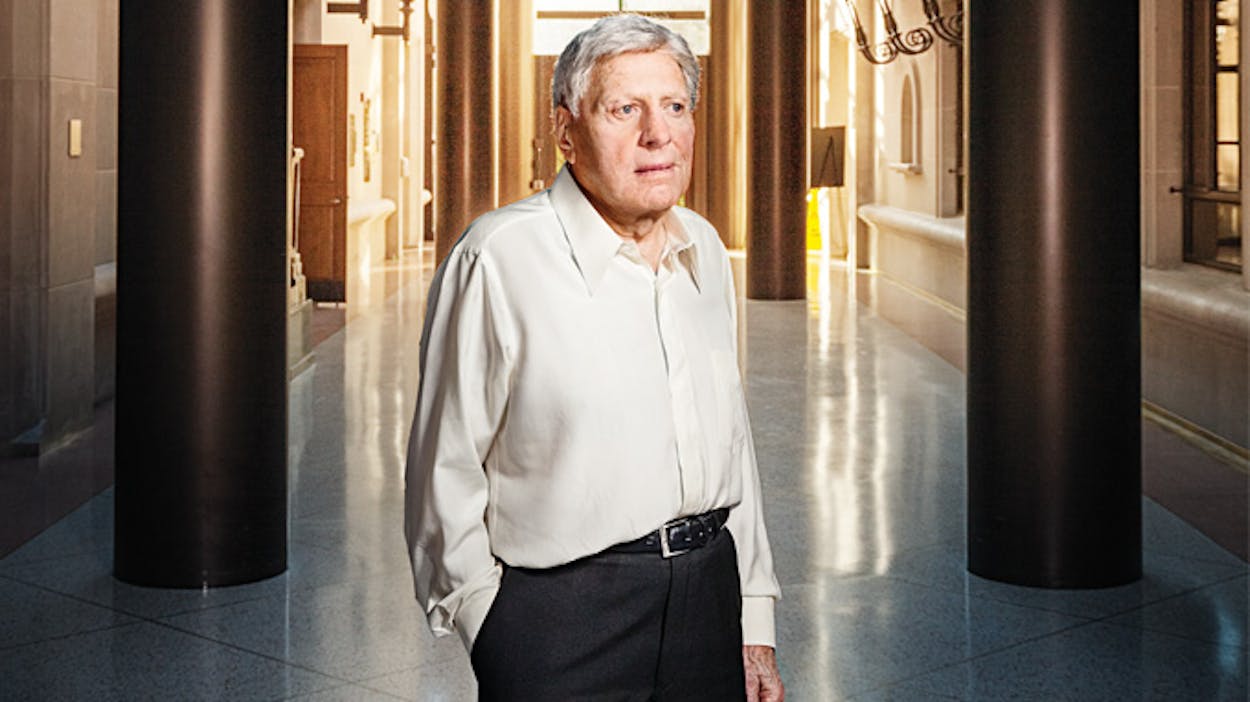

Not one bit of that turmoil was evident in Joe Jamail’s suite at DKR, and certainly not on the face of its host—and not because Jamail didn’t have a dog in those hunts. One of the most generous benefactors in UT history, he counts Brown, Dodds, and Powers among his dearest friends. More to the point, he’s Brown’s personal attorney; any move to ax Mack will have to go through Jamail. But since he also happens to be the greatest trial lawyer who ever lived—and damn well aware of it—he doesn’t let such trivial weekday irritants as Perry and his regents intrude upon game day. When the first half ended, he grabbed his cane and whipped off the eye patch he wears to help him focus on the field—his halting gait and failing vision being the only indicators that he really is 88 years old—and started moving through the skybox, directing his guests to get another drink.

It was time for Joe Jamail to hold court. Halftime in his box feels a little like Don Vito’s home office during a wedding at the Corleone compound. All the Orangeblood royalty stops in. Other big givers pay their respects like the heads of the five families. Lesser mortals admire the photos on the wall showing the Longhorns running onto the gridiron under a grand archway bearing the name “Joe Jamail Field.” The fridge stays open for beers to fly out, and at the center of it all beams the white-haired Jamail, ready for business and small talk.

One of the first through the door was Austin city council member Sheryl Cole, who introduced her husband, Kevin, as a proud UT law grad. Dodds came in and congratulated Jamail on his recent birthday. Then Edith Royal approached. The widow of the stadium’s namesake takes in all the games in Jamail’s box, and on this day she’d waited until halftime to ask him for a favor.

“Joe, I need you to call Willie for me,” she said in a voice so sweet she could have played grandmother to every fan in the stadium. She was referring, of course, to the redheaded country star, an erstwhile running buddy of Jamail and her husband’s. “The state cemetery called and said they have a plot for Willie near Darrell, and I’d like you to bring it up with him. Have you talked to him lately?”

“We talked the other day,” said Jamail. “He’s in Stuttgart.”

“That makes sense,” she said. “I got an email on Thursday from Mickey, and he said he was in Germany.” Thinking that “Mickey” required an elaboration that “Willie” did not, she turned to me. “Mickey is Willie’s harmonica player. Mickey Raphael.” I thanked her.

“Shit, Edith, I’ll tell him, but we both know what he’ll say,” said Jamail. “He’s going to say, ‘I don’t want to be f—ing buried.’ ”

“Well, if you’d just mention it, I’d appreciate it.”

“Of course,” said Jamail.

Others stopped in, including Austin investor Steve Hicks, one of the pro-Powers regents. He and Jamail shook hands and exchanged a confident nod, prompting Jamail to recap the previous night’s Distinguished Alumnus Awards ceremony at the LBJ Presidential Library. “You should have seen the reception before the honorees’ speeches. It was like a damn pep rally. When Powers walked in, the whole room burst into applause. They licked Powers so hard he looked like he’d been through a f—ing car wash.” But that was as close as Jamail would come to discussing any unrest. I asked him about the honorees’ speeches, which I’d heard had been overwhelmingly supportive of Powers. “How the f— would I know? They closed the bar after the reception, so I got the hell out of there. I don’t know why they don’t have that f—ing event somewhere like the Four Seasons. I love that bar at the Four Seasons.”

He’d been more eager to talk about the forces coming to bear on his beloved UT when I’d met with him earlier in the week at his Houston office. “Perry wants to make a trade school out of UT,” he complained. “He got some regents to go along with that to kiss his ass, but Powers resisted it. And he resisted Perry’s plan to decrease tuition. Perry didn’t like any of it. One thing Perry’s got to understand is, we impeached one goddam governor for fooling with the University of Texas.”

According to Jamail, Powers’s job is safe. “As I understand it, Perry can’t get the five votes he needs to get rid of him.” But that hardly tempered Jamail’s distaste for Perry loyalists. “I think Wallace Hall is an imbecile,” he said, referring to the UT regent who personally launched an investigation of Powers and the UT Law School Foundation’s controversial loan program with a series of massive open-records requests—for which he is now himself being investigated by the state House for misuse of office. Just as irksome to Jamail, Hall also reached out to Alabama coach Nick Saban’s agent to gauge Saban’s interest in replacing Brown. “Mack called me when that happened, and everybody saw my statement: You want to f— with his contract? Get ready to be sued.

“If Mack decides to leave,” he continued, “I’m sure Saban will look at the job. But right now Mack has no intention of leaving. The regents have said they’ve no intention of firing him. Powers has said it. DeLoss has said it. The ex-students’ association is totally behind him, and that’s the alumni. Red McCombs and I are behind him, and that’s a lot of money. There’s a vocal minority of fans who’ve booed him here recently, but hell, I’ve heard them boo when we’re winning. They used to boo Chris Simms when we were thirty points ahead. Mack’s contract runs through 2020. I know; I drew it up. If he feels like he’s played his string out before that, he’ll quit. But Mack will go out on his terms. The rest of this is bullshit.”

And it’s the kind of bullshit that Jamail keeps outside his box. Just before the second half started, he pulled me aside. Talking to Edith about Darrell and Willie had reminded him of something. “When Frank Broyles coached at Arkansas, he used to have a golf tournament each year for all the Southwest Conference coaches. Darrell asked me and Willie to go with him one time—not to play, but just to be together. Afterward, Darrell brought Willie out to pick a few songs for everybody. At some point Willie hit a wrong note or something, and he said, ‘Ah, f— it.’ The old Baylor coach Grant Teaff was there, and he stood up and said, ‘This is a Christian group here. We’ve brought our wives. And we don’t appreciate that kind of language.’ Willie didn’t miss a beat. He started another song and sang:

Jesus was a Baylor Bear

But Jesus wouldn’t cut his hair

His helmet didn’t fit

But Jesus didn’t give a shit

’Cause Jesus was a Baylor Bear

“And then we got up and got the hell out of there.”

Shortly thereafter the Horns retook the field, and Jamail returned to his seat at the front of his box. Midway through the third quarter, just about the time three-hundred-pound Longhorn defensive tackle Chris Whaley returned a fumble recovery 40 yards for a touchdown—“You know,” said Jamail, “he came here as a running back, and he can sure as hell still run like one”—a giant chocolate birthday cake showed up at Jamail’s seat, courtesy of the UT athletic department. It was a three-tiered masterpiece that looked like the groom’s choice at a $100,000 wedding reception. Jamail said thanks, asked the server to put it on the buffet, and then, turning to the field and adjusting his eye patch, promptly forgot all about it. The Longhorns were rolling again.

They’d go on to win 35–13, buying Brown one more week of relative calm. But in subsequent weeks, after the Horns squeaked by woeful West Virginia 47–40 in overtime and then got drummed by Oklahoma State, 38–13—the most lopsided home loss of Brown’s tenure—the calls for Brown’s head would resume. Not even a 41–16 manhandling of Texas Tech on Thanksgiving day would quiet the critics. When Jamail defended the coach to an Austin American–Statesman sportswriter after the OSU debacle, fans aimed their vitriol at him, threatening to topple his statues on campus, Saddam Hussein–style. The old lawyer, who went to his first UT game in 1942, refused to let up, partly because he wanted to shift attention off Mack, but mostly because he loves a good fight even more than beating OU. “Tell them to send me my money back, and then they can pull the statues down,” Jamail said over the phone the morning after the Tech game. “I don’t know who the hell those f—ing crybabies on the Internet are. Could be Aggies or the Taliban, for all I know. Or f—ing al Qaeda. Because every real UT fan is proud of this team and the way they’ve turned their season around.”

*Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Bellmont Hall as Belmont Hall. We regret the error.

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football

- Mack Brown

- Joe Jamail