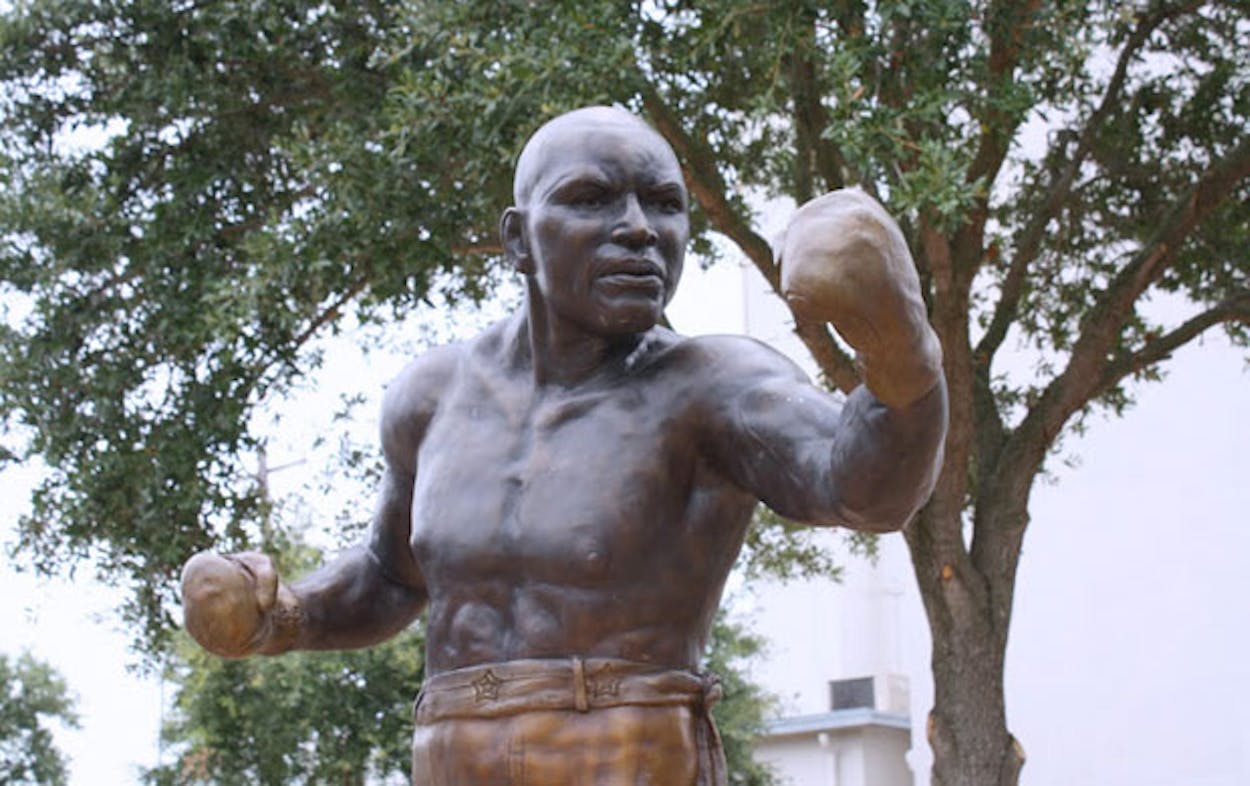

Jack Johnson stood on a pedestal behind Old Central Cultural Center, ready to throw a left hook and then come back with a right. On the grounds surrounding the life-size, bronze statue of the first black heavyweight boxing champion workers dug trenches in preparation for the opening of what will be Jack Johnson Park, Galveston’s latest effort to reclaim its most famous son since turning its back on him a century ago.

The workers were asked if they are fans of Johnson.

“No,” one man said flatly.

“I hadn’t even heard of him until this project,” another man said.

This lack of awareness is no surprise in this island community. It has long wrestled with its relationship to the dockworker-turned-fighter who grew up at 8th and Broadway and went on to break down cultural barriers fifty years prior to the civil rights movement.

“What he overcame is so significant,” said Ken Burns, whose 2005 documentary about Johnson, Unforgivable Blackness, spawned an ongoing posthumous-pardon campaign for Johnson’s trumped-up violation of the Mann Act. The law, written to address the “white slave” hysteria, forbade interstate transport of women for “immoral purposes,” and was curiously applied to Johnson because of his relationship with Belle Schreiber, a white prostitute, which took place prior to the law going into effect. “He felt that it was his right to live out the promise of the Constitution,” Burns added. “His approach was so fresh in its individuality.”

In 1910, Johnson easily defended his championship against James Jeffries, a.k.a. “the Great White Hope,” the former champion who came out of retirement, as Jack London had earlier suggested he do, to “remove the golden smile from Johnson’s face.” That year Galveston announced a homecoming parade in Johnson’s honor, but once it was learned that he would attend it with Hattie McClay, a white woman, the festivities were cancelled.

Since then in Galveston, several unsuccessful attempts have been made to pay tribute to Johnson. In the late 1980s, a statue was erected in Menard Park, but it was impressionistic and hard to identify as Johnson, and was razed after being riddled with bullet holes and hurricane damage. At the same time, 41st St. was renamed Jack Johnson Blvd. But it is not an attractive road to travel down. Also, last year the artist Earl Jones carved Johnson out of a tree stump ravaged by Hurricane Ike. Its significance was diminished by the outcry it elicited because of its location in the new Oaks subdivision.

Not until Jack Johnson Park has there been a concerted attempt at lionizing the boxer.

“The city paid $150,000 to do this park,” Douglas Matthews, coordinator of the project, said in a phone interview prior to meeting at Old Central on Juneteenth, “because we want to apologize for what the city officials didn’t do back then.”

Matthews, the former city manager of Galveston, seems an odd torchbearer for Johnson. Like Johnson, Matthews was born and raised in Galveston, enjoyed athletic success (he was a star running back at Central High School), and was a standout in his career field (he was the first black city manager in Texas). But his approach was fundamentally different. Matthews worked his way through the system, while Johnson bucked it.

“Not all black people are proud of Jack Johnson,” Matthews said. “Some families don’t want him as a role model. They think he was an ‘uppity Negro.’”

But Johnson is an icon exactly because he refused his place. He drove fast cars, wore sharp suits and was a skilled musician. He spoke loudly, candidly, and wielded a mighty pen. He was way ahead of his time, and that made him one of the most feared men in America.

“Johnson represented the perfect anti-hero because everyone was alienated by him pushing his freedoms,” said Casey Cutler, a white male with a mixed-race family who describes himself as a “citizen soldier for doing what’s right in Galveston.”

Cutler came up with the idea for Jack Johnson Park, inspired by Johnny Valentine, the now-deceased longshoreman who advocated for Jack Johnson Blvd. and the statue that was torn down. When the Galveston Housing Authority solicited public input for how to rebuild the Magnolia Homes public-housing development, which was destroyed in Ike, Cutler, who lived near there for thirty years, pitched integrating green parkland into the plan.

Some said it was not the right location for memorializing Johnson. Others said it would compromise how much public housing could be rebuilt. Ultimately, deep-seated politics won out and the plan was nixed. But Matthews took it and ran to Old Central.

“The Jack Johnson Park and statue is not some linear equation,” Cutler said. “It is, at the very least, quadratic.”

Jack Johnson Park exists not just as a truce with Johnson, but also as a way to empower Galveston to face its past as a slave market and its present as a tourist destination. A park dedication is tentatively planned for October, and Muhammad Ali, who was celebrated for doing exactly what Johnson was criticized for, is expected to attend.

“With enemies all around him—white and even black—who were terrified his boldness would cause them to become a target, Jack Johnson’s stand certainly created a wall of positive change,” Adrienne Isom, the Austin sculptor who created the statue, wrote in an email. “Not many people could dare to follow that act.”